Along with the Civil War, the American Revolution is one of the two most iconic events in American history. The Revolution has inspired countless myths, been used as a political weapon, and is at the heart of American civic religion. Generations of Americans have honored and commemorated the Revolution by erecting monuments to various peoples, places and events. In recent years, monuments to the Confederacy have come under scrutiny, with many arguing they were erected as symbols for white supremacy and that they served to promote the “lost cause” narrative of the Civil War. Given this controversy, Americans have been forced to reconsider Confederate monuments. Who built them? When were erected? Why were they constructed? What do the monuments represent? The same questions can be asked about monuments built to the American Revolution. I have compiled a database of approximately 450 monuments, memorials, statues, and plaques to the American Revolution across the country. While this is not a completely exhaustive list, it does allow general conclusions about the patterns, trends, and broader themes of Revolution monuments.

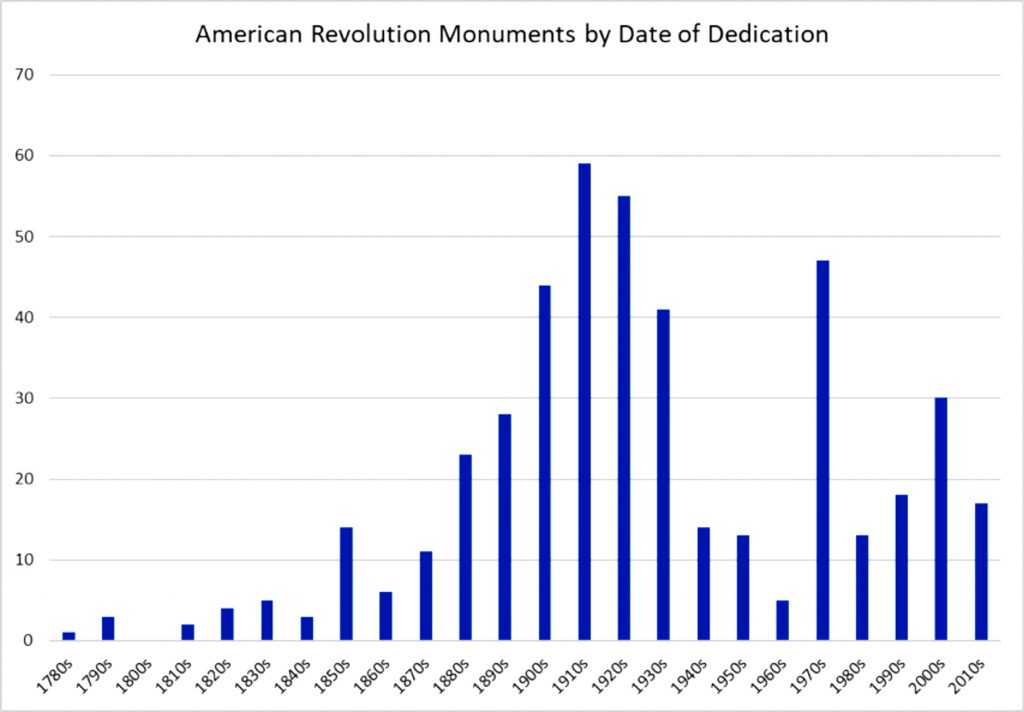

Chronologically and thematically tracing the history of American Revolution monuments from the first memorials in the late eighteenth century to recent ones erected within the previous decade shows that there have been several important changes to the monuments over the last 240 years. Until the mid-nineteenth century, there were relatively few memorials to the Revolution, and those that were built were generally dedicated to the leaders of the Revolution or men who had taken up arms. These monuments frequently accused the British of being cruel and dishonorable enemies. The 1890s to the 1930s saw the greatest surge in monument building, largely driven by recently-formed lineage groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution. In this era, monuments were more diverse, with memorials dedicated to Patriot women like Margaret Corbin, and foreign officers such as Casimir Pulaski. The British were also portrayed more sympathetically. These changes were driven by political and social developments in the United States. Women sought to highlight their political participation in the Revolution as they pushed for the right to vote, and the mass immigration of foreigners encouraged newcomers to seek recognition for the role of their ethnic groups in establishing American independence. The British were no longer considered barbaric as Anglo-American relations improved. After a period of relatively few monuments from the 1940s through the 1960s, there was another surge with the bicentennial in 1970s. In the years since, the greatest development has been the increased recognition of black Patriot participation in the Revolution, with monuments erected across the country to honor their service. Despite these changes, there has also been some continuity in the memorials. The themes have largely remained the same since the late 1700s, with monuments consistently emphasizing the patriotism, unity, and sacrifice of the American Patriots who fought for freedom.

Monuments to the American Revolution were rare prior to the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike the aftermath of the Civil War, there were few veterans’ organizations to fund the construction of monuments and the United States lacked the industrial capacity to build them.[1] The first memorial was authorized by Congress on January 25, 1776, which was to be dedicated to Gen. Richard Montgomery, killed at Quebec in December 1775. Congress resolved that Montgomery had given worthy examples of “patriotism, conduct, boldness of enterprize, insuperable perseverance, and contempt of danger and death.” To honor his patriotic sacrifice, Congress ordered that “a monument be procured from Paris, or any other part of France, with an inscription, sacred to his memory.”[2] Wartime exigencies prevented the structure’s completion until 1787, when it was dedicated at Saint Paul’s Church in lower Manhattan. A few monuments were erected in the 1790s. Jean-Antoine Houdon, a French sculptor, produced a statue of George Washington between 1785 and 1791 which was placed in the capitol rotunda in Richmond.[3] In Lexington, Massachusetts, the state legislature funded the construction of a monument dedicated in 1799, commemorating those who died at the first engagement of the Revolutionary War. Other early memorials included an 1828 monument to Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko at West Point, and an obelisk in Baltimore dedicated to George Washington constructed between 1815 and 1829. The handful of monuments built during this era were disproportionately concentrated in the northern states.

Early monuments often emphasized the perceived barbarity of the British, while they stressed that Americans fought for their individual and national freedom. The 1799 Lexington monument honored the men who were “the first Victims to the Sword of British Tyranny & Oppression,” adding that these individuals “Defend[ed] their native Rights” and “nobly dar’d to be free!!” Erected in 1817, a monument in Paoli, Pennsylvania, memorialized the dead of the 1777 battle, stating, “Sacred to the memory of the Patriots who on this spot fell a sacrifice to British barbarity.” Similarly, the Groton Monument in Connecticut recognized the “The Brave Patriots, who fell in the massacre at Fort Griswold” when fighting against a crown force commanded by “THE TRAITOR, BENEDICT ARNOLD.”[4] In 1833, a monument was erected to honor Americans killed in the 1778 attack on the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. The memorial praised the “small band of patriotic Americans” who unsuccessfully tried to fight off “a combined British, Tory and Indian force” but said of crown forces that “wide-spread havoc, desolation, and ruin marked his savage and bloody footsteps.” [5] These early monuments illustrate that Americans at this time believed the generation before them did their patriotic duty in the name of freedom against a barbaric enemy.

The first real increase in American Revolution monuments took place in the years leading up to the Civil War, as the revolutionary generation disappeared and the nation split in two. Most memorials continued to be built in the north, but the monuments recognized many peoples and events. An obelisk in Needham, Massachusetts, honored those who had fallen at Lexington, while a monument in Westchester County, New York celebrated the three men who had captured John Andre and foiled Benedict Arnold’s plot to turn West Point over to the British. The 1850s also saw one of the earliest monuments in the South, the Washington Light Infantry Monument erected in 1856 to commemorate the American victory at the Battle of Cowpens.[6]

There are two likely reasons why monuments increased in number just before the Civil War. First, the last men of the Revolution were dying off. By the time of the Civil War, only a handful of veterans were living, and Americans sought to honor a passing generation.[7] Secondly, the American Revolution served as a unifying event for a nation that was being rent asunder. Monuments helped reinforce the unity between North and South, which had fought together to defeat Great Britain. A monument erected in Pennsylvania to commemorate the Battle of Crooked Billet addressed disunion directly. It adhered to the common theme of British barbarity, saying that the Americans were “cruelly slain” by the British when fighting for “American liberty.” But it also added, “The Patriots of 1776 achieved our independence. Their successors established it in 1812. We are now struggling for its perpetuation in 1861. The Union must and shall be preserved.” With this statement the memorial emphasized the Revolution’s legacy of national unity, a central reason for the uptick of monuments in this era.

Several monuments were put up for the Revolution’s centennial during the 1870s and 1880s. On April 19, 1875, the Concord Minuteman statue was dedicated at the Old North Bridge, one-hundred years to the day after the war began. Facilitating the erection of memorials, Congress began funding the construction of certain monuments. In New York, an obelisk celebrating the victory at Saratoga received $95,000 in congressional funding, and the structure was completed in 1883.[8] In 1881, Congress allocated $100,000 to build a monument at Yorktown to commemorate the decisive battle of the war. This disbursement completed the objective of a congressional resolution from 1781 to build a monument to the Franco-American victory.[9] At least one centennial monument was dedicated to a British soldier. A stone was placed by an American millionaire to John André where he had been hanged in Tappan, New York, ninety-nine years earlier. The monument noted that men in both armies mourned someone “so young and so brave” and the inscription softened the anti-British rhetoric that had appeared on many monuments. The inscription observed that the stone was placed “not to perpetuate the record of strife, but in token of those better feelings which have since united the two nations.” A monument to André, who was considered a British spy, proved controversial, and an attempt was made to destroy the monument with dynamite in 1882.[10]

The greatest surge in monuments to the Revolution took place from the 1890s through the 1930s. The primary reason for this expansion was the foundation of lineage groups, namely the Sons of the American Revolution, founded in 1889, and the Daughters of the American Revolution, founded in 1890. The Society of the Cincinnati also contributed to the proliferation of monuments. Originally established in 1783 as a hereditary society for American and French officers, seven of the individual state societies were defunct by the late 1830s. All seven of those societies, however, were reorganized between 1881 and 1899. These organizations were at the forefront of monument building, raising money for plaques, statues, and memorials. They provided an organized means of raising funds to build monuments which did not previously exist. For example, the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati gave a statue of George Washington as a gift to the city of Philadelphia, which was dedicated in 1897.[11] Among the many monuments built by the Daughters of the American Revolution during this era was a granite boulder monument to Patrick Henry in 1922.[12]

Most early monuments were dedicated to the Revolution’s leaders or to men who bore arms, but the early 1900s saw the emergence of monuments to women, which coincided with the apex of the women’s suffrage movement. The first monument to revolutionary women was built in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1896. It honored women who gathered water from a nearby spring despite knowing that British-allied Indians and Loyalists laid in wait to ambush the fortified settlement. By gathering water per their normal routine, the women deceived the crown forces into believing they were unaware of their presence and were able to bring more resources into the community. Funded and erected by the Lexington Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, the structure is said to be the first monument built “by women—for women.”[13] Women such as “Molly Pitcher” had monuments erected in their honor. Molly Pitcher is generally believed to have been Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, who may have carried water to soldiers at the Battle of Monmouth and then manned an artillery piece after her husband was wounded and incapacitated. In 1916 a statue was erected at Molly Pitcher’s gravesite in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Margaret Corbin was likewise honored for her service. Corbin’s husband was killed at the Battle of Fort Washington in 1776, and she took his place on the artillery crew, aiding in firing the cannon. She was severely wounded after being hit by grapeshot in the chest, shoulder, and jaw and had to be carried away from the front line.[14] In 1909, a memorial was dedicated to her in Manhattan at the battle’s location, while another was built seventeen years later in Highland Falls, New York, were she had died in 1800. Deborah Sampson, the most famous woman to formally enlist in the Continental Army, received a monument in Plympton, Massachusetts, the town of her birth, in 1906. As women fought for the right to vote, they were increasingly recognized as having played an important role in winning the Revolution.

Some of the most prominent figures to be honored in this period were foreigners who aided the Revolution, particularly Friedrich Von Steuben, Casimir Pulaski, Tadeusz Kościuszko, and the Marquis de Lafayette. The National German-American Alliance strongly advocated for statues of Von Steuben, the Continental Army’s drillmaster, and eventually succeeded in having statues placed at Valley Forge and in Washington, D.C.[15] Casimir Pulaski statues were built in several American cities during this era, including Providence, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C. A monument was dedicated to Pulaski in 1929 in the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts, which was densely populated with Polish immigrants. That same year, Congress passed a resolution establishing General Pulaski Memorial Day each October.[16] In Chicago, which had also seen significant Polish immigration, the Kosciuszko Society successfully campaigned for a statue of the Polish engineer, which was dedicated in 1904. Between 1890 and 1910, statues of Lafayette, Von Steuben, the Comte de Rochambeau, and Tadeusz Kościuszko were erected in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. Monuments to these foreigners enabled immigrants to latch on to the memory of the American Revolution, because they could celebrate the role of their countrymen in founding the nation.

One of the most memorialized individuals during the surge of monument building was Nathan Hale. A young schoolteacher from Connecticut, Hale was tasked in 1776 with spying on British forces in New York City. Hale was captured and hanged as a spy on September 22, 1776 at the age of twenty-one. As early as 1846, Hale’s hometown of Coventry, Connecticut, had dedicated an obelisk to him. Between 1886 and 1940, statues and monuments were dedicated to Hale in Hartford, New Haven, New London, Manhattan, Huntington (New York), and Washington, D.C. To many Americans, Hale represented the epitome of patriotism and sacrifice, and his Hartford statue, located in the capitol building, was inscribed with his supposed final words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”[17]

With improving Anglo-American relations and the alliance during the world wars, more monuments were dedicated to the British and depicted them as honorable enemies. In 1895, a small monument was erected at the Guilford Courthouse battlefield in memory of Lt. Col. John Stuart, who was killed in the battle. The marble marker acknowledged it was built “in honor of a brave foe.” A monument was dedicated in 1914 by the Frances Bland Randolph Chapter of the DAR to British Maj. Gen. William Phillips in Petersburg, Virginia. Philips is buried there, having died of disease in 1781, and he remains one the highest-ranking British military officers buried in the United States. When a small memorial was dedicated on the Brandywine battlefield in 1920 it made no distinction between those who had died on either side, instead simply stating “In Memory of Those Who Fell in the Battle.” In 1930, a monument was erected to Patrick Ferguson at the King’s Mountain battlefield, where he had been killed in 1780. The monument said that Ferguson was “A soldier of military distinction and honor” and added that “This memorial is from the citizens of the United States of America in token of their appreciation of the bonds of friendship and peace between them and the citizens of the British Empire.” Between the 1890s and 1930s, Americans shifted away from their early tendency to depict to British as cruel enemies, instead portraying them as misguided but honorable foes.

While several monuments were erected to British soldiers in this era, this was generally not the case with African Americans or American Indians. Black Patriots were almost entirely written out of the history. The only exception to this pattern was an 1888 monument on Boston Common to Crispus Attucks and the other victims of the Boston Massacre. Native Americans were sometimes recognized as having been important actors during the Revolution but were portrayed in different ways. Indians who sided with the British were depicted as uncivilized savages. When an obelisk was built in 1912 commemorating the Battle of Newtown, it honored John Sullivan for “destroying the Iroquois Confederacy” and “opening westward the pathway of civilization.” A statue of George Rogers Clark in Charlottesville, Virginia, was dedicated in 1921, and titled him the “Conqueror of the Northwest.” He sits prominently on a horse, towering over Indians in his front, while several armed men follow him forward. The Bryan Station monument honoring women in Lexington, Kentucky, noted that the women “faced a savage host in ambush.” Natives who sided with the rebelling colonists, such as Wappinger sachem David Nimham, were depicted more favorably. Nimham was a captain in the Stockbridge Militia, an Indian unit which served in the Continental Army. He and many others were killed at an engagement in what is now the Bronx. In 1906, the Bronx chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a monument to Nimham and the other Stockbridge Indians, stating that they “as allies of the Patriots, gave their lives for liberty.”

New monuments declined in number from the 1940s through the 1960s but saw a significant resurgence during the 1970s with the bicentennial. One of the most prominent bicentennial monuments was the Signers of the Declaration of Independence Memorial on the National Mall, built by the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration. Other monuments to the great men of the Revolution were erected for the bicentennial. In Maryland, Havre de Grace built a statue to Lafayette, commemorating his assistance in helping name the city.[18] Casimir Pulaski was honored with a statue in Hartford. The most commonplace monument for the bicentennial were small memorials within local communities honoring those who took up arms during the Revolution. Towns and counties across the country, ranging from Westfield, Massachusetts, to Chemung County, New York, to Dickson County, Tennessee, dedicated small and simple memorials for those who served.

Monuments from the 1970s onward increasingly recognized the diversity of the American Revolution. Women have continued to be commemorated for their role in the Revolution. Sybil Ludington, a teenage girl who supposedly warned of a British attack, received a statue in Danbury, Connecticut in 1971.[19] A statue of Deborah Sampson was unveiled in Sharon, Massachusetts, in 1989. Men in the service of foreign armies have also been recognized, with Bernardo de Galvez, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana, having been honored with two statues in Washington, D.C.; he was granted honorary United States citizenship in 2014 for “risking his life for the freedom of United States citizens.”[20]

The most significant evolution in recent monuments has been the new emphasis on the role of black men in the Revolution. Black Patriots have at last been recognized for their service to the war and sacrifice for American freedom. In 1982, the black soldiers of the First Rhode Island Regiment were honored with a small monument in Westchester County, New York, for their service “in defense of America’s freedom.” A larger monument was dedicated to the First Rhode Island Regiment in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 2005. More recently, in 2012, a monument was erected to the black Patriots of the Revolution in Washington, Georgia. The monument emphasizes that black Americans, “some free and others enslaved—fought for freedom. Every freedom, every sacrifice, every hardship of each patriot is the foundation for today’s freedoms.” In 2009, a monument was dedicated to Haitian soldiers who fought under the French flag alongside the Americans at Savannah in 1779.

Given the controversy surrounding Confederate monuments in recent years, it is impossible not to draw comparisons and contrasts between memorials to the Confederacy and the Revolution. A significant similarity between the two is the time period in which most memorials were constructed. Many observers have commented that most Confederate monuments were not built until decades after the Civil War. This pattern is also true for American Revolution monuments. Very few were built in the immediate aftermath of the war; rather, monuments were not erected in significant numbers until the 1850s. The spike in Revolution monuments from the 1890s through the 1930s also closely parallels the construction of Confederate monuments.[21] In both cases, lineage groups advocated for and funded the construction of many monuments. Indeed, the Daughters of the Confederacy was founded just four year after the DAR. Another reason for Revolution monuments in the decades after the Civil War was that it served as a symbol for the unity of the nation. It helped bind the country through its common origins because northerners and southerners had joined together to gain their national independence. This theme is best illustrated by a monument on the Guilford Courthouse battlefield in North Carolina. Dedicated in 1904, the small monument reads “No North Washington” on one side and “No South Greene” on the other. Washington, a southerner, spent most of the war in the North, while Greene, a northerner, led the campaign that ultimately won the war in the Carolinas.[22]

In other ways, however, Confederate and American Revolution monuments differ. Although the thirteen colonies were far from united, with perhaps fifteen percent of the population remaining loyal to the king, one of the central themes in Revolution monuments is unity of the American people. Americans have honored the Revolution as the event which unified the disparate colonies and created American nationhood. Conversely, Confederate monuments commemorate those who served in the cause of American disunity. Secondly, monuments to the Revolution have come to celebrate the racial diversity of the revolutionaries, which Confederate monuments cannot accurately commemorate.

Over the course of 230 years, monuments to the American Revolution have seen both change and continuity. Modern memorials no longer accuse the British of being barbarians, and today’s monuments much more accurately reflect the diverse nature of the Revolution, including women and African Americans. Patterns in the erection of monuments followed broader trends in society. Statues were built to honor foreigners who fought for the United States, often by immigrant communities who wanted to emphasize the role of their nation in creating the nation. Monuments for women began to appear in greater numbers in the early 1900s, during the suffragette movement. Likewise, the critical service of black Patriots was increasingly recognized in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. At the same time, several basic themes in the monuments have remained the same. From 1776 to the present, these monuments have consistently emphasized unity, patriotism, freedom, and sacrifice.

[1]Jim Percoco, “Revolutionary War Monuments: The Revolutionary War in Four Minutes,” YouTube video posted by “American Battlefield Trust,” November 21, 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=55&v=uNCeTvvs3ks.

[2]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 4: 90.

[3]Tracy L. Kamerer and Scott W. Nolley, “Rediscovering an American Icon: Houdon’s Washington,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Autumn 2003, www.history.org/foundation/journal/autumn03/houdon.cfm, accessed July 31, 2019.

[4]Francis Manwaring Caulkins, ed. Emily S. Gilman, The Stone Records of Groton (Norwich, CT: The Free Academy Press, 1903), 58.

[5]The Valley of Wyoming: The Romance of its History and Poetry, also Specimens of Indian Eloquence (New York: Robert H. Johnston, 1866), 44.

[6]U.S. National Park Service, Washington Light Infantry Monument, www.nps.gov/cowp/learn/historyculture/washington-light-infantry-monument.htm, accessed August 1, 2019.

[7]For an examination of some of the last surviving veterans, see Don N. Hagist, The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2015).

[8]U.S. National Park Service, Saratoga National Battlefield Brochure, www.nps.gov/sara/planyourvisit/upload/2015_MON_brochure.pdf, accessed August 1, 2019.

[9]Yorktown Centennial Commission, Report of the commission created in accordance with a joint resolution of Congress, approved March 3, 1881, providing for the erection of a monument at Yorktown, Va., commemorative of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1883), 3-4.

[10]Julian Harris Saloman, “Andre Monument in Tappan,” South of the Mountains28, no. 4 (October-December 1984): 6-11.

[11]Ceremonies attending the unveiling of the Washington monument in Fairmount Park and presented to the city of Philadelphia by the state Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania Saturday, May 15th, 1897(Philadelphia: Press of Allen, 1897).

[12]“Patrick Henry Monument,” Daughters of the American Revolution, www.dar.org/national-society/historic-sites-and-properties/patrick-henry-monument

[13]Randolph Hollingsworth, “‘Mrs. Boone, I presume?’ In Search of the Idea of Womanhood in Kentucky’s Early Years” in Bluegrass Renaissance: The History and Culture of Central Kentucky, 1792-1852, eds. James C. Klotter and Daniel Rowland (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 101.

[14]Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle of America’s Independence (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 138-319.

[15]U.S. Congress, Senate, National German-American Alliance: Hearing Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate Sixty-Fifth Congress Second Session on S.3529 a Bill to Repeal the Act Entitled “An Act to Incorporate the National German-American Alliance,” Approved February 25, 1907, 65th Cong., 2nd sess., 1907, 137-138.

[16]“Joint Resolution To Provide for the observance of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the death of Brigadier General Casimir Pulaski, Public Resolution No. 16,” U.S. Statutes at Large 46 (1931): 28.

[17]For the memorialization of Nathan Hale, see Virginia DeJohn Anderson, The Martyr and the Traitor: Nathan Hale, Moses Dunbar, and the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), chap 10.

[18]Erika Butler and David Anderson, “Havre de Grace’s Lafayette statue is a tribute to United States’ Bicentennial, city’s name,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 2017, www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/harford/aegis/ph-ag-hdg-lafayette-statue-20170623-story.html, accessed August 2, 2019.

[19]The monument was a smaller version of a statue dedicated ten years earlier to Ludington in Carmel, New York. Ludington’s ride is almost certainly a myth, but the story has been used by Americans to shape and create narratives about our national history. See Paula D. Hunt, “Sybil Ludington, the Female Paul Revere: The Making of a Revolutionary War Heroine,” The New England Quarterly88, no. 2 (June 2015): 187-222.

[20]U.S. Congress, House, Conferring honorary citizenship of the United States on Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gálvez, H.J.Res.105, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., introduced in House January 9, 2014, www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ229/PLAW-113publ229.pdf.

[21]“Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy,” 2016, Southern Poverty Law Center, www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/com_whose_heritage.pdf. See pages 14 and 15 for a chart showing when Confederate monuments were erected.

[22]Niels Eichhorn, “Empty Pedestals and Absent Pedestals: Civil War Memory and Monuments to the American Revolution,” Journal of the Civil War Era, September 12, 2017, www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2017/09/empty-pedestals-absent-pedestals-civil-war-memory-monuments-american-revolution/.

9 Comments

This seems like an impressive amount of work.

Do you have any future plans to open the monuments list to viewers?

That’s something I have considered, if others would find it useful. In the meantime, I’ll keep updating the database as I come across new monuments.

Excellent article. As I started collecting old postcards showing RevWar monuments a few months ago, your list would be invaluable to me! While there is no statue to George Washington upon British soil, there is a statue of him in London. When the statue was sent from Virginia in 1924, it was acompanied by crates of dirt, with instructions to place the dirt beneath the statue. The reason given was that Washington had vowed to “never set foot on British soil” !

Thanks for this article. My 7th grade students’ favorite monument to the Revolution is the Boot Monument at Saratoga, a monument to Benedict Arnold (described as “the most brilliant soldier” but otherwise unnamed). It shows Arnold’s leg which was wounded at Quebec and Saratoga, and was erected in 1887.

Very nice article. Another study of monumentation/commemoration, focused on Saratoga, is by Donald Linebaugh, “Commemorating and Preserving an Embattled Landscape”, found in The Saratoga Campaign: Uncovering an Embattled Landscape (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England,2016), pgs 229-258).

A very interesting article.

I’d love to know more about the immediate postwar and how Loyalists dealt with the defeat and remembered the revolution and war. From what I’ve read so far in Brannon’s book, Patriots and Loyalists worked together to bury the hatchet and allow the country to become unified again in the postwar years – a very American way of dealing with such a problematic issue. The fact that there were few suggests Brannon is right: the two sides were somewhat silent on the war in the immediate postwar period. Neverthelss, it would be interesting to know how loyalists reacted to any early monuments that were dedicated to Patriots and how they dealt with the suggestion that they were supporters of a barbaric side.

Any chance you could now share your list ? Thanks !

What about the Battle of Bunker Hill Monument completed in 1843 commemorating the first battle, or at least one of the first battles, of the American Revolutionary War? Lafayette helped lay the cornerstone.

Otherwise, thanks for compiling this data.

I wish to pass along another American Revolutionary Monument dedicated in 2022 in the Town of Fishkill, NY in the mid Hudson Valley, the home of the once Wappinger tribe. The last Official Wappinger Sachem was Daniel Nimham. He would be mostly known fighting and dying for the American Cause with a group of Indians called the Stockbridge Militia, based in Stockbridge NY.

Making the sculpture of Daniel Nimham became a 20 year journey for me, of intense research and study which I am still continuing after the dedication. For more information, pictures and a film about the making of the sculpture: “Creating the Sachem Daniel Nimham Sculpture”, and the Wappinger and Mohican Stockbridge please visit my webpage below.