The Treaty that Redefined North America

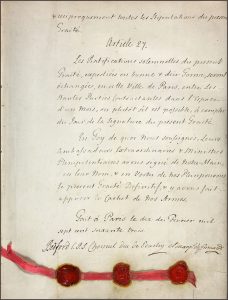

On Wednesday August 10, 1763, crowds of Bostonians gathered after nightfall and stood watch over the harbor. Under the glow of the bonfires that lined the town’s shoreline, the people assembled to view a fireworks display, which signified the importance and special nature of the occasion: Earlier that afternoon, at one o’clock, Governor Francis Bernard read King George III’s proclamation of peace. The Treaty of Paris 1763 had ended the French and Indian War (1754-1763).[1]

The peace negotiators called the Treaty of Paris 1763 the “Definitive Treaty of Peace and Friendship.” The Treaty redrew the physical map of North America and changed the way the British Empire governed its colonies. The Treaty also prompted King George III to issue a royal proclamation that redefined relationships between Europeans and Native Americans. Bostonians greeted the Treaty of Paris 1763 with exuberant fanfare because it promised a lasting peace.[2]

For the first time ever, Great Britain’s copy of the Treaty of Paris 1763 is on display in North America.[3] In honor of the 250th anniversary of the Treaty, the 1763 Peace of Paris Commemoration—a coalition of partners and funders including state and national chapters of the Society of Colonial Wars—joined forces with the Bostonian Society to bring the victor’s copy of the Treaty to Boston. The Treaty that redefined North America will be on display at the Old State House through October 7, 2013.

Old State House Council Chamber

Visitors will find the Treaty on display in the Council Chamber at the Old State House. Throughout the war, the Council Chamber served as the “war room” of Massachusetts. The Governor filled the room with maps of New France (Canada), New England, New York, the Atlantic seaboard, the Caribbean islands, and New Spain, which he and his advisors used to follow the progress of the war and to plan military operations for Massachusetts’ provincial forces.[4] From the east-facing window of the chamber, the Governor and his councilors watched soldiers embark for New France and the Canadian Maritimes from the Long Wharf. According to Bostonian Society Historian Nathaniel Sheidley, the Council Room stood “at the center of [Massachusetts’] staging of the war.”

Undoubtedly the thunderous booms of the August 1763 fireworks display reminded many colonists of artillery explosions and gunfire, which might have triggered a recollection of their experiences with combat. The Treaty of Paris 1763 exhibit highlights the Treaty of peace by presenting it alongside several artifacts of war. The exhibit curators borrowed Governor Spencer Phips’ 1755 proclamation declaring the “Penobscot tribe of Indians to be Enemies, Rebells, and Traitors to his Majesty King George the Second.”[5] The proclamation promised bounties to soldiers who brought Penobscot prisoners and scalps to Boston: £50 for each Penobscot male above twelve years old; £25 for women and boys under twelve years old; £20 for the scalps of Females and boys under twelve years old.[6]

New Map of North America

The Treaty of Paris 1763 redrew the map of North America. The articles of the Treaty favored Great Britain, which as the victor received the West Indian islands of St. Vincent, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada, two Grenadines, and all lands east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans, which went to the Spanish.[7] Visitors can visually grapple with the change in geography just as contemporary Britons did, with the “New Map of North America” printed by Carrington Bowles in London in 1763. An original edition of the map hangs in the Council Chamber. The map quotes articles from the Treaty to explain the new boundary lines.[8]

Cultural Encounters with Peace Making

At the end of the French and Indian War, delegates from Great Britain, France, and Spain gathered in Paris, France and negotiated acceptable peace terms. These representatives did not consider Native Americans as they made peace.

Native Americans in the Great Lakes region and the Ohio and Illinois countries felt betrayed by their French allies who ceded Canada and all lands east of the Mississippi River—Native American lands—to the British. Several Native American leaders, among them an Ottawa war chief named Pontiac, united Native American peoples with the goal of using arms to push the British east of the Appalachian Mountains. By the end of 1765, the Native American alliance dissolved when both the British and Native Americans reached accommodations that included recognition of Native sovereignty and acceptance of the British presence.[9]

A nine-row wampum peace belt on display near the Treaty highlights the differences between European and North American peace-making customs. Whereas a select group of elites made peace in Europe, entire communities made peace in North America. Prior to a peace negotiation, Native American communities came together to make wampum belts. Belts reflect the handiwork of dozens of women, usually family heads. Upon arriving at a peace conference, the community-elected delegates exchanged and circulated wampum peace belts as a sign that they would negotiate in good faith and with the backing of their respective communities. Colonists also made and exchanged wampum belts with Native American peoples. Wampum peace belts symbolized active community assent to and acceptance of peace.[10]

Limitations of the Peace of Paris 1763

The Bostonians’ fireworks display illustrates the joy with which they received the news of peace and demonstrates their pride in the British Empire. The people of Massachusetts believed themselves to be the freest people in the world because they were British subjects. The actions of the colonial governors of Massachusetts to engage in the war, the House of Representatives to raise funds to support the war, and the willingness of Bay colonists to fight in the war speak to the colonists’ desire for a collaborative relationship with their London-based rulers. After the war, the colonists wanted to be more involved in the empire, not less.[11]

The Treaty of Paris 1763 made the British Empire the largest empire in history. British holdings in North America included vast territories of unorganized lands in the continental interior and more than thirty organized colonies on the eastern seaboard and in the Caribbean. Great Britain needed a substantial amount of money and military support to protect these lands. In addition, the war doubled the imperial debt to approximately £146,000,000. In an effort to govern these new territories and service its financial obligations, the King and Parliament endeavored to closely manage the North American colonies, impose new taxes upon them, and enforce trade duties that the colonists had long ignored. These actions constituted a dramatic departure from the small, local, and representative governance to which the colonists had been accustomed.[12]

The “Definitive Peace” embodied in the Treaty of Paris 1763 did not bring the long-lasting peace the Bostonians had hoped for on August 10, 1763. Violent colonial protestations against the Stamp Act erupted in 1765 and by 1775, war once again raged in North America. Only this time, the war emerged as one for independence from the British Empire, not the spread of it.

[1] The Treaty of Paris 1763 ended a war that spanned nine years and four continents (North America, South America, Europe, and Asia). North Americans called the war the French and Indian War while the Europeans knew it as the Seven Years’ War. “Boston, August 12, 1763,” The Boston Post-Boy & Advertiser, August 15, 1763, Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers, 1690-1922; “Boston, August 15,” The Boston Gazette, August 15, 1763, Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers, 1690-1922.

[2] Historians specify 1763 when discussing the Treaty of Paris made in 1763 to differentiate that treaty from the Treaty of Paris negotiated in 1783. The Treaty of Paris 1783 ended the American War for Independence.

[3] According to Donald C. Carleton, Jr., Project Director of the 1763 Peace of Paris Commemoration, France lent its copy of the Treaty of Paris 1763 for display at Historic New Orleans about five years ago. The National Archives of the United Kingdom loaned the Treaty of Paris 1763 for display in the Old State House.

[4] Five men served as Governor of Massachusetts between 1754 and 1763: William Shirley, Spencer Phips, Thomas Pownall, Thomas Hutchinson, and Francis Bernard.

[5] The Massachusetts Historical Society loaned the proclamation to the Bostonian Society for this exhibit.

[6] The Penobscot people still remember Phips’ proclamation as a notorious and controversial document. “Wabanaki Timeline – Phips Proclamation | Abbe Museum,” accessed August 19, 2013, http://abbemuseum.org/research/wabanaki/timeline/proclamation.html.

[7] The French gave New Orleans to the Spanish as part of a secret Franco-Spanish agreement, which they reached prior to the signing of the Treaty of Paris 1763. France also ceded Senegal, Minorca, two posts in Sumatra, all posts established in India after 1749, all posts in Hanover and Brunswick, Germany, and agreed to evacuate the Rhineland and give it to the King of Prussia. Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, First Vintage Books Edition (New York: Vintage Books, 2001), 565–566; William M. Fowler, Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America, 1754-1763 (New York: Walker & Company, 2005), 268, 272, 505–506.

[8] Richard H. Brown lent the map to the Bostonian Society for this exhibit. Louis Stanislas De La Rochette engraved the new map, which Carrington Bowles of London printed in 1763.

[9] Anderson, Crucible of War, 620–632; Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 278–314.

Recent Articles

Dr. Warren’s Crucial Informant

John Dickinson and His Letters

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

Recent Comments

My family is descended from Luther Kinnicutt. We have discovered information about...

We all have a bias toward believing that our own contribution to...

Thank you! I grew up in Middlesex County during the Bicentennial, so...