Brevet Major General Peter Muhlenberg woke up in the ruins of Fort Littleton on the morning of March 6, 1784, mounted his horse, and continued his journey through the snow-covered mountains of western Pennsylvania.[1] With him were a servant, a pack horse, and a German veteran of Casimir Pulaski’s Legion.[2] They rode to Bedford, site of another French and Indian War fort, on the Forbes Road.[3] The general found warm accommodations at a tavern but prudently kept a low profile. He was an important man, and he had no desire to get drawn into the controversies of the day. He could not, however, avoid hearing people talk.[4]

I had flattered myself that, as we were going towards the frontiers, we should soon be out of the latitude of politics; but even here two men cannot drink half a gill of whiskey without discussing a point in politics, to the great improvement and edification of the bystanders. Especially so to me, while I stand by incog[nito], and hear the name of Muhlenberg made use of, sometimes in one way, and sometimes in another; for were I known, I believe no one would have the hardiesse to mention that name with disrespect, and look at me, for I have at present the perfect resemblance of Robinson Crusoe: four belts around me, two brace of pistols, a sword and rifle slung, besides my pouch and tobacco pipe, which is not a small one. Add to this the blackness of my face, which occasions the inhabitants to take me for a travelling Spaniard, and I am sure that my appearance alone ought to protect me from both politics and insult.[5]

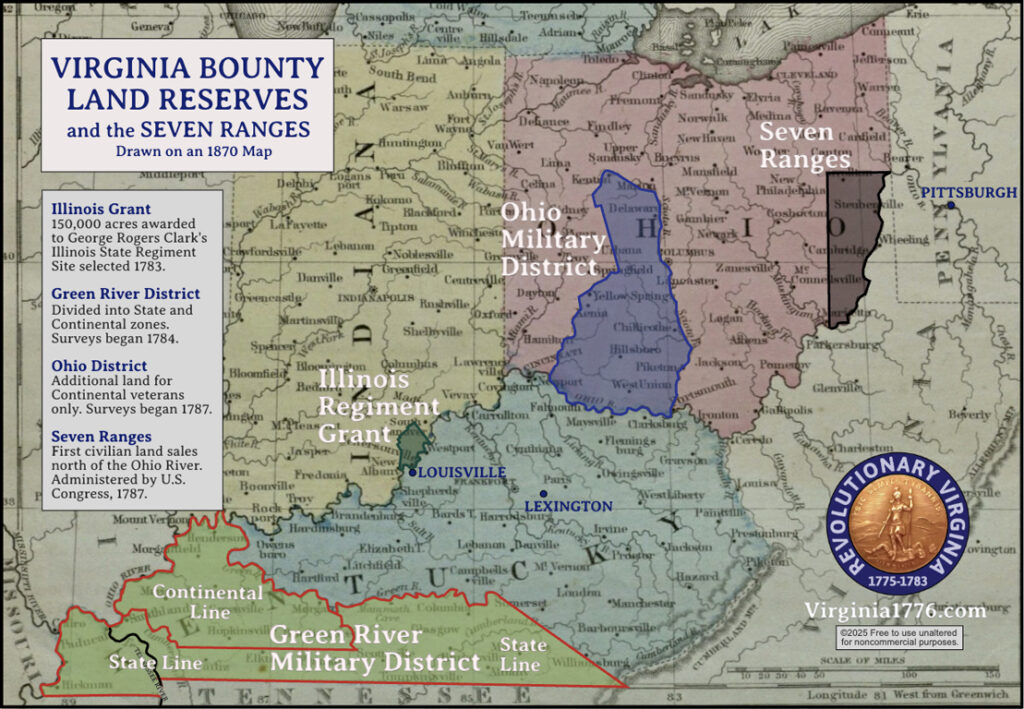

Though he had returned to his original Pennsylvania home after the war, the Fighting Parson was now one of the “superintendents” appointed to “locate the lands intended for the officers and soldiers of the Virginia line on Continental establishment.”[6] The Pennsylvania Dutch general was personally entitled to 13,333⅓ acres.[7] If he gave his warrant to the principal surveyor by March 15, he would have a chance at the best land. He had nine days left to get to Pittsburgh.

Collecting Warrants

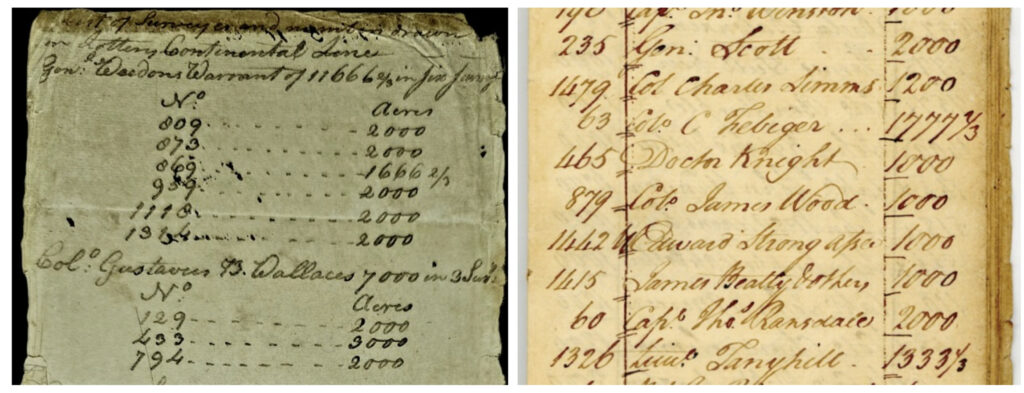

Richard Clough Anderson was the chief surveyor for Virginia’s Continental Line. William Croghan was the chief deputy and acting chief surveyor for the State Line. Veterans had been sending them their warrants for weeks, each endorsed on the back. Officers with large grants noted the number of surveys they wanted with their sizes. “I too precipitately yesterday determined on the number of surveys that wou’d suit best for my land in Cantucky,” wrote Capt. James Pendleton the day after delivering his warrant. “I am apprehensive it will put you to some trouble but must request that you will alter ye no. from four to two surveys and that one Contain two thousd acres & the other ye balance of the Warrant.”[8]

Lieutenant Colonel Anderson and Major Croghan left Richmond for Kentucky on February 19.[9] They rode 330 miles north to Pittsburgh. From there, they planned to float down the Ohio River to Fort Nelson at Louisville. They had been prisoners together during the war, and the business they were beginning now drew them still closer. They both married sisters of Gen. George Rogers Clark.

More warrants came to them as they traveled. A “much disappointed” Col. Thomas Gaskins arrived in Richmond a week after their departure. “The uncommon severity of the winter rendered it impossible for me to cross Rappahanock river till a few days past, which prevented me from having the pleasure of seeing you & furnishing you with a Marque agreeable to my promise.” It was now less than three weeks from the warrant deadline, and Gaskins was worried. “I have it now with me & shall if possible send it after you tho am afraid it will not be in my power.” Cognizant that his letter and its enclosure might arrive late, he leaned in: “Shall depend on your Friendship in doing me all the justice in your power.”[10] Gaskins gave his warrant to Capt. Edward Carrington, who forwarded it in the hands of Capt. Abner Crump.[11] A March 6 letter from Carrington indicates that some latitude was given in such cases.

Owing to the inattention of some of Colo. [James] Innes’s friends his land warrant did not get to your hands before you left this place. Capt. Crump will now deliver it to you, and his rec[eip]t for it being before the 15th of March you may adopt as your own act if you please and put the warrant on the footing of others. The principles on which those of Stevens, Lawson, and Parker have been admitted into the common lot I think apply well to this zealous officer and I hope the superintendents present will give their consent for its admission. [12]

Carrington noted that his brother, Capt. Mayo Carrington, would represent him in the selection of his land. He was not confident in Mayo’s ability to judge, and asked Anderson to assist, specifying that he wanted good soil as near to navigable water as possible. “I have lately determined to attempt the getting into the next assembly and have the most flattering hopes of succeeding,” he wrote, proposing, “let the officers to the westward take care of my interest there, and I will, in turn, support theirs here.”[13] Carrington was, in fact, elected to the Assembly that convened that May.[14]

To Louisville by Flatboat

Anderson and Croghan met Peter Muhlenberg at Pittsburgh on March 10. There was a crowd of veterans there, waiting for the river to thaw. Muhlenberg noted, “Colonel Anderson was kind enough to offer me passage on his boat, which is nearly ready, and to carry one horse for me.”[15]

As they waited, the Kentucky-bound Virginians socialized and did business together. Muhlenberg met the deadline to deliver his warrants to Colonel Anderson. They included several warrants carried for others, including one for Friedrich Wilhelm, Baron de Steuben, and some State Line warrants, which he gave to Major Croghan. Muhlenberg had a special relationship with Steuben because of their shared German heritage.[16] Killing time, Muhlenberg attempted to go fishing but was thwarted by lingering ice.

Finally, on March 28, Anderson’s boat was ready to go. Flatboats were raft-like vessels made for one-way river travel. They were disassembled at their destinations, where their wood was repurposed. Anderson’s boat was large enough to carry a heavy load of supplies, fifteen men, and nine horses.[17] It took an entire day to load it.[18]

Muhlenberg, Anderson, and Croghan departed in a three-boat convoy on March 31 and covered an average of sixty miles of river over the first three days. Two more flatboats joined them on the way. They stopped to hunt, explore some of the off-limits Ohio Military District, and exercise the horses.[19] Muhlenberg wrote:

As we were anxious to see the Land between Sciota & Miami, we lay by three or four days in different places. . . . They fully answer my expectations, and exceed any Lands I have hitherto seen in Quality and are delightfully stockt with Buffaloe & other Game. This is to be understood of the Lands within 4 & five mile of the river. I did not care to venture further for fear of losing my Scalp.[20]

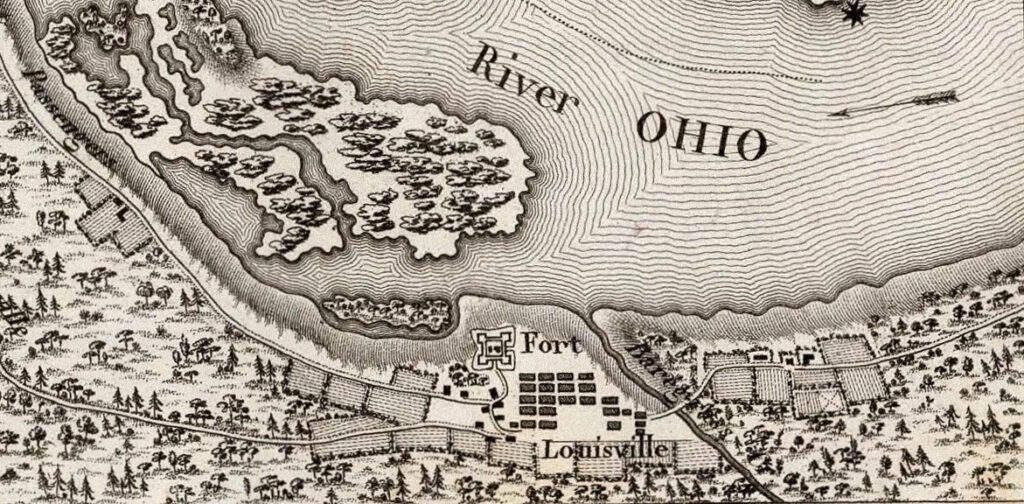

They pulled into Beargrass Creek opposite Fort Nelson on April 11. The town there was chartered four years earlier and named for America’s great ally, King Louis XVI of France. Muhlenberg noted that Louisville consisted of “a court-house, a jail, and seven huts, besides the fort.” The arrival of a general and several senior officers was a big event. The commandant of the fort, Maj. George Walls, saluted them by firing three cannons.[21] Walls had, when a captain, endangered the Christmas attack on Trenton by crossing the Delaware early to avenge the death of one of his men.[22]

The superintendents set up shop inside the fort and put the warrants under lock and key. Muhlenberg wrote to Kentucky’s three county lieutenants (militia commanders) to arrange protection for surveying parties.[23] The general discerned quickly that Indian diplomacy had been neglected. “I found three Shawanees here who were come on an embassy from the Nation to request a treaty,” he cautioned in a letter. “They seemd much alarmed at first, on finding so many Warriors assembling here, and pretended to think that mischief was intended ag[ains]t them. I explained the matter as well as I could, & a few presents, with a little Whiskey put them perfectly in humor again.” The “southern Indians” (the Chickamauga Cherokee), however, “had lately destroyd several Families in the vicinity of this place” and were unlikely to be so easily placated. “The Indians near Cumberland are it seems, totally unapprised of our coming down. This may induce them to march ag[ains]t us, which certainly would not have been the case, had proper Measures been taken.”[24]

The Continental and State Lotteries

Virginia avoided the chaos of individuals staking claims by requiring a lottery. The law required that “priority of location ought to be determined by lot . . . under the direction and management of the principal surveyors and the superintendants.”[25] Surveys were limited to “good lands,” but each veteran naturally wanted the best land he could get. Flat bottomland along a navigable waterway was especially prized. Commissioned officers drew their own lots, but enlisted men drew lots in “classes” totaling 1,000 acres each, then drew again to determine priority within the class. For warrant holders who skipped or missed the lottery, site selection would be done on a first-come, first-served basis. Continental surveys would move to the Ohio reserve when all of the good land in the Green River District was gone.[26] Veterans did not have to select their land in person, but claimants acting by proxy had to pay a fee of $1 for every 100 acres.

It took several days to prepare the ballots, organize the selection classes, and conduct various other tasks. The sabbath was observed, and Muhlenberg, who had loved hunting and fishing his whole life, took that afternoon to go fishing.[27] He did better with his line here than he had at Pittsburgh.

we now live as perfectly wild as if we were totally in the wilderness. Bear, buffalo, venison, turkey, and fish form our whole and sole diet. The fish caught in the Ohio are large and excellent in quality. . . . As our whole dependence for living is on hunting and fishing, we take it by turns, and I have this day caught eleven fine perch, besides some catfish.[28]

The lots were drawn in the third week of April. It took the Continentals two days and the State regulars one day.[29] The total number of Continental lots was 1,485.[30] Lot number one, the very first choice of land, was drawn by or for Dr. William Brown, a surgeon from Fairfax County who had been physician general of the army’s Middle Department.[31] Men who drew high numbers often held them until the Ohio Military District opened. Muhlenberg informed Steuben, “You have been rather unfortunate in drawing. The numbers are 663 = 810 = 1037.” He emphasized, however, that the key to finding good land was “to have people in pay who have explord & are well acquainted with the Country.” He added, “I have two of these with me, & you may depend Sir that nothing in my power shall be left undone, in order to render you locations as valuable as possible—one of them at any rate must be laid [on] Sciota, and if I find that it will be more to your advantage I shall lay two of them on Sciota, as for the first it will do very well on Cumberland.” He apologized for his “incoherent” letter, joking that “a Man must write wild who has for a Month livd on nothing but Bear & Buffaloe.[32]

“My own tickets were rather high in both,” Muhlenberg lamented to his diary, “so that Sciota will probably be the place on which I shall chiefly have my view.” In fact, two of his numbers were quite good. He drew 213, 294, and 1347.[33] He traded a thousand acres of his Scioto River land to Maj. George Slaughter, a former subordinate, for a plot of land nine miles from Louisville.[34] Slaughter should have kept this valuable land. He died penniless in 1818.[35]

The Illinois Land Lottery

Two weeks later, at the same place, the officers of the Illinois Regiment got to work dividing up their 150,000-acre prize. Their land was then in Illinois County, Virginia, but is now primarily Clark County, Indiana. The General Assembly had appointed four “gentlemen” and six veteran officers of the Illinois Regiment to serve as a board of commissioners to oversee the process.[36]

The first step had been to collect claims from veterans who believed themselves eligible. There were no warrants; it was up to the commissioners to decide who qualified. Notices were posted at the three Kentucky District courthouses, and commissioners were appointed to collect claims in each county.[37]

The deadline for turning in claims was April 1, 1784. The commissioners convened the next day to start making tough eligibility determinations. Any of Clark’s original volunteers who had declined to enlist in the Illinois Regiment were deemed ineligible. Veterans whose service began after the award statute was adopted on January 2, 1781, were also excluded. Maj. George Walls, the commandant of Fort Nelson, was one of these, despite his prior Continental service. Soldiers who had not served for at least three years were cut out, even if they had participated in the capture of Kaskaskia. Officers who resigned their commissions within twelve months of the taking of Kaskaskia were disqualified. Officers’ allotments were determined by their ranks on January 2, 1781, not their ranks at the war’s end.[38]

The commissioners may have been strict because their calculations required it. The grant’s 150,000 acres were not enough. Ordinary soldiers consequently received just 100 acres, a third of what was originally promised. Sergeants were given 200 acres. The commissioners decided to give Clark, the only brigadier general, 7,500 acres. This was 2,500 less than a standard brigadier’s award. The other officers received standard amounts for their ranks. This left 19,500 acres for late claims and other contingencies. This “residue” dwindled to 10,800 acres and was proportionally distributed in 1788.[39]

The commissioners may have been strict because their calculations required it. The grant’s 150,000 acres were not enough. Ordinary soldiers consequently received just 100 acres, a third of what was originally promised. Sergeants were given 200 acres. The commissioners decided to give Clark, the only brigadier general, 7,500 acres. This was 2,500 less than a standard brigadier’s award. The other officers received standard amounts for their ranks. This left 19,500 acres for late claims and other contingencies. This “residue” dwindled to 10,800 acres and was proportionally distributed in 1788.[39]

Illinois Grant Bounty Land Allocations

| Rank | Initial Acres | Residual

Distribution |

Total |

| Soldier or sailor | 100 | 8 | 108 |

| Sergeant | 200 | 16 | 216 |

| Subaltern | 2,000 | 156 | 2,156 |

| Captain | 3,000 | 234 | 3,234 |

| Major | 4,000 | 312 | 4,312 |

| Lt. Colonel | 4,500 | 351 | 4,851 |

| Colonel (none) | |||

| Brig. General | 7,500 | 549 | 8,049 |

The Illinois District was surveyed before distribution and divided into lots no larger than 500 acres.[40] William Clark was appointed principal surveyor and completed his work quickly. The commissioners approved his map on July 9, 1785. Then, as had been done for the Kentucky and Ohio reserves, a lottery was held to determine selection priority. On December 12, 1785, the commissioners appointed Abraham Hite and Edmund Rogers to draw “the classes and numbers,” while Walter Davis and William Croghan recorded “the names of the respective claimants and the numbers they drew.”[41] Officers drew multiple lots while private soldiers were grouped into classes of five.

A Rough Start for Surveying

Work in the Green River District faced immediate obstacles. The county lieutenants failed to organize a militia guard. The militia law’s draft-dodging penalty, six months’ service in the Continental Army, was rendered toothless by the end of the war.[42] James Logan of Lincoln County replied to Muhlenberg and Clark on April 27, explaining other problems.

If you had been pleased to informd me how those men was to been suported it would have incuraged me to have indeavourd to sent them. But it apears to me impose able to Raise a Guard with out provition. Therefore I have not attempted it. The Governor signifies to me the Superintendents are to furnish provitions. He also in forms me the Guard is for the porpose of Attending the surveyers in the Execution of there Office, which l would suppose from his instructions the men ought to be Immediately Marched to the Lands Alloted for the Army. However, if my own services as an indevidual would render any benefitt to either of the Lines I would Chearfully wait on them. But to Order Millitia out on such principles as having no provisions & going so far out of there way to the Lands Alloted for the Army I can not think it is practable.[43]

Frustrated, Muhlenberg convened the superintendents. They agreed to use money from the survey fund to hire guards and to bring along two “grasshoppers,” small brass cannons, from the fort.[44] Nevertheless, the superintendents began to doubt the expeditions’ feasibility. They faced danger from the angry Chickamauga, interference from squatters, and summer foliage would soon make wilderness travel difficult. The erstwhile priest wrote in his diary:

Many people are concerned in claims in that country, which they have no chance of obtaining, unless they can prevent our going there, and on this account many people here are strangely prejudiced and throw every obstacle in our way they possibly can. Though it is certain we shall be able to do very little this summer in the surveying business on account of the thickness of the woods and weeds. This consideration has induced me to think seriously of returning, and waiting for an opportunity when we can survey.[45]

Legitimate preemption and treasury warrant settlers were concerned that the surveys might start an Indian war. News from Fort Pitt appeared to prove them right.

In the evening several boats arrived from Fort Pitt, by whom we received intelligence that the Indians had a few days ago killed and scalped two men near Fort Wheeling, and cut off the head of one of them. This last circumstance, viz., the cutting off the head of one of the men, is looked upon by those who are best acquainted with the customs of the Indians as a declaration of war, or as a challenge to the friends of the killed to revenge their death.[46]

Muhlenberg called a meeting of the remaining officers. After a “long and tedious debate,” they decided to send a small team of surveyors to divide the district into State and Continental zones, but to postpone lot surveys to October. There was an immediate outcry, evidently from enlisted men who were far from home and could not afford two trips to Kentucky. Muhlenberg recorded that “some gentlemen are very violently in favor of proceeding immediately on this business, and urge it with warmth, notwithstanding all the obstacles that seem to forbid it.” An accidental injury brought his own ability to participate into doubt. He visited former army surgeon Alexander Skinner, who further assessed that his “constitution” was not up to it.[47] The general had contracted malaria during the war and would eventually die from it.[48] Despite failing even to hire paid guards, it was decided that “the superintendents should proceed immediately to explore the country, return by the 1st of August, and lay the locations before the Board.”[49] Muhlenberg, feeling coerced, was not happy with the decision.

They are to explore and locate the country without a guard, and without provisions, except what they can carry on their backs. They are to be obliged to run risks which few men would wish to undertake for others; and when perhaps this matter is determined on, few or none of those men who are at present so violent, will undertake the danger and fatigue. . . . I wish I may conjecture wrong when I think that one-half will never return; that much money will be expended on it, and the business remain unaccomplished.[50]

The Continental superintendents divided their zone into three sectors. They planned to head out in pairs, each with a paid guide who would earn five dollars a day. The State superintendents got similarly organized. The State-Continental division line surveyors headed out on May 12, and the other teams left on May 14.[51] General Clark stayed back to oversee work on the Illinois Grant distribution. William Croghan continued to fill in for him on the State Line work and took over completely when Congress called on Clark to negotiate peace (and land cessions) with the Indians.[52] When Indians killed Walker Daniel, the able and ambitious Croghan took over as administrator for the Illinois Grant commissioners, too.[53] He leveraged his positions and his acumen to amass a personal fortune.

Returning Home

On May 15, Muhlenberg wrote in his diary that Fort Nelson, “where we have hitherto quartered, is now almost desolate.” Only a few families undergoing smallpox inoculation remained.

He rode to Cox’s Station, near modern Bardstown. Colonel Anderson was there with a man named George May. May was the original surveyor of Kentucky County and an active investor in quickly appreciating land.[54] Anderson and Muhlenberg jointly purchased 200,000 acres from him. Then Muhlenberg headed home, likely to address the financing. Traveling alone was unwise, so he followed the usual practice of joining an assembly of strangers at English’s Station, near Crab Orchard.

Upon mustering, the company was found to consist of forty-two men, one woman, and three negroes, who were armed with nineteen guns, several brace of pistols, and some swords. From this place we have now to go one hundred and twenty miles to the next cabin or station, twenty-five miles to the next, and forty to the one after … as we have some reason to apprehend danger from the Indians, we have determined to march regularly, and to guard our camp at night, to prevent a surprise.

By “regularly,” he meant “in military formation.” On the first night, they camped three hundred yards off the path and slept in the open with no shelter but the trees. “It rained very hard during the whole night,” he wrote with the good humor that comes from hard experience, “but to make amends, we were regaled with an excellent concert by the wolves.” The third day was the most alarming.

We passed several graves where persons had been interred who were killed by the Indians; though in fact they cannot be called graves, as they only raise a pile of old logs over the bodies to prevent the wolves from devouring them. At 11 o’clock we passed a place where the Indians last year formed an ambuscade within six or eight yards of the road, and fired upon ten persons who were going to Kentucky. They killed nine out of the ten; the tenth, a girl of ten years of age, was thrown off her horse, knocked on the head with the butt of a gun, and scalped. She was found on the same day by a travelling company, who carried her to Kentucky, where she is still living. The other nine were thrown into a hole, where a tree had been blown up by the roots, and a pile of logs thrown upon them.

The grisly sights continued. After lunch they came to a section the general thought was “not improperly” called the “Shades of Death.”

It lies on a small creek between two mountainous precipices, and is covered so thickly with laurel, that the beams of the sun cannot penetrate at noonday. In the midst of the valley we found the bones of several human bodies, on which probably the wolves had made a repast. I proposed making a halt in order to bury them, but the gloominess of the place prevented the motion from being seconded.

As they crossed the Cumberland Gap, they came to a spring where they “found the bones of two grown persons and a child, who were butchered there last year while they were drinking.” Finally, when they crossed the Clinch River, they began to relax. The sight of John Anderson’s blockhouse in Carter’s Valley marked their return to civilization.[55]

Surveys Suspended

Virginia, meanwhile, was in the process of giving away its land across the Ohio River. “It is a well known fact of our revolutionary history,” Virginia legislators recalled in an 1834 committee report, “that the … state of Maryland absolutely refused to ratify the articles of confederation until some satisfactory arrangement should be made of the vast western domain. No subject, indeed, so much distracted the councils, and disturbed the harmony of the colonies, as that of the uncultivated territory.”[56] Congress had put the heat on, resolving a year before the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781:

That it appears more advisable to press upon those states which can remove the embarrassment respecting the western country, a liberal surrender of a portion of their territorial claims, since they cannot be preserved entire without endangering the stability of the general confederacy; to remind them how indispensable it is to establish a federal Union on a fixed and permanent basis, and on principles acceptable to all its members; how essential to public credit and confidence, to the support of our army, to the vigour of our councils, and the success of our measures, to our tranquillity at home, and to our reputation abroad, to our present safety and future prosperity, to our very existence as a free, sovereign and independent people.[57]

“Thus,” the Richmond legislators boasted, “at a most critical juncture, did Virginia make upon the altar of the public good, the most magnificent sacrifice perhaps ever recorded in the history of states; generously giving up a treasure which would have enriched her through all future time.”[58] In doing so, however, it withheld settlement rights in the Illinois Regiment’s 150,000 acres and the larger zone between the Scioto and Little Miami Rivers for its Continental veterans.[59]

The United States had wrested most of the continent east of the Mississippi from Britain, and Congress intended to likewise assert possession by right of conquest against Britain’s defeated Native allies. In the interim, Congress continued to observe the 1768 treaty line (the Ohio River and a meandering line that followed parts and branches of the Allegheny, Susquehanna, and Delaware rivers) as the western limit of settlement. Certain states and many individuals were not so patient. Thousands of veterans who had been demobilized into an economic crisis saw the West as their best opportunity.[60] From Fort Pitt, Brig. Gen. William Irvine reported that “great numbers of Men have crossed the Ohio, and have made actual settlements in different places from the River Muskingum to Wabash.”[61] Though collocated with land promised to George Rogers Clark by the Piankashaw Miami,[62] Natives and Congress alike viewed activity in the Illinois Grant as a perilous violation of the riverine boundary. Clarksville, the town chartered by Virginia for the zone’s administration, was already “settling fast,” which Muhlenberg feared would “give rise to an immediate quarrel.”[63]

Samuel Hardy, chairman of the Committee of the States (which ran things when Congress was in recess), wrote to Virginia’s governor in August to caution: “Should an Indian War be brought in consequence of steps taken” by Clark’s men, “the Cession of Virginia now relied on as a principal fund for redeeming the public securities of the United States, would prove an expense and disadvantage to the Union rather than a source from which any pecuniary Assistance could be drawn.”[64] Hardy, who was a Virginia delegate, added that Congress had appointed commissioners to negotiate “a General Treaty of Peace with the Indians,” but asked that the Commonwealth take “effectual steps” to prevent settlement north of the Ohio in the meantime.[65]

Far from Clarksville, Major Croghan’s survey team reached the Tennessee River in August and found the valley and the land beyond it settled by the Chickasaw. This was the most-desired land in the State Line zone, but all they could do was “number the warrants, and to make entries” based on the “vague information” they possessed.[66] Settlers elsewhere “earnestly represented to the legislature of Virginia, that if the State Line surveys were persisted in, the infant and defenceless settlements in Kentucky would be involved in all the horrors and calamities of an Indian war.”[67]

This, combined with Hardy’s rebuke, prompted the General Assembly to instruct Gov. Patrick Henry to halt surveys in the Illinois Grant and beyond the Tennessee River “for such time as he may think the tranquility of the government may require.” This was done on January 6, 1785.[68] Because the treeless “barrens” east of the Tennessee were regarded as inferior land, this had the effect of almost entirely suspending State Line surveys until further notice.[69]

[1] Peter Muhlenberg, “General Muhlenberg’s Journal, 1784,” in Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army (Carey and Hart, 849), 425-427.

[2] Worthington Chauncey Ford, et al., eds., Journals of the Continental Congress: 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Library of Congress, 1904–1937), 19:106-107; C. Leon Harris, transc., “Enlistments, Muster Rolls, and Pay Rolls of Gen. Pulaski’s Legion, March 1779 to November 1780,” Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters, https://revwarapps.org/b222.pdf.

[3] William A. Hunter, Forts of the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1753-1758 (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1960), 410-424.

[4] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 427. For Bedford inns and taverns see “Notes and Queries,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 39 (1915), 228-230.

[5] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 427-428.

[6] Ibid., 425.

[7] Muhlenberg, Life of Muhlenberg, 291. Land awards were given according to actual (not brevet) ranks at the end of the war.

[8] James Pendleton to Richard Clough Anderson, January 23, 1784, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 2, pp.1-3, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[9] Pennsylvania Packet, February 26, 1784, cited in Gwynne Tuell Potts, George Rogers Clark and William Croghan: A Story of the Revolution, Settlement, and Early Life at Locust Grove (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2020), 124-125n10.

[10] Thomas Gaskins to Anderson, February 25, 1784, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 2, pp.6-7, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[11] John H. Gwathmey, Historical Register of Virginians in the Revolution (1938; reprinted Genealogical Publishing, 2010), 196.

[12] Edward Carrington to Anderson, March 6, 1784, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 2, pp.9-12, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Cynthia Miller Leonard, The General Assembly of Virginia, July 30, 1619-January 11, 1978 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978), 153.

[15] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 428-429; Gwathmey, Virginians in the Revolution, 275.

[16] “Extract of a Letter of Richard Claibornes to Colo. R.C. Anderson dated Philada. 17 June 1785,” Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 3, pp.24-27, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[17] Peter Muhlenberg to the Baron de Steuben, April 23, 1784, M0367, box1, folder 25, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis.

[18] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 429.

[19] Ibid., 429-432.

[20] Muhlenberg to Steuben, April 23, 1784.

[21] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 435-436.

[22] Adam Stephen to Jonathan Seaman, January 5, 1777, Adam Stephen papers, 1749-1849, Library of Congress, Washington; David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 231-232.

[23] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 437, 442.

[24] Muhlenberg to Steuben, April 23, 1784.

[25] Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, October 1781 session (Richmond: Thomas W. White, 1828), 27. William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes At Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, 13 vols. (various publishers, 1821-1823), 11:311.

[26] Hening, ed., Statutes, 11:309-313.

[27] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 438. Theodore G. Tappert and John W. Doberstein, trans., The Journals of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, 3 vols. (Muhlenberg Press, 1945), 1:699. When Peter was a teenager, his father wrote that his “chief fault and evil bent” was toward “hunting and fishing,” but “not toward the gen[us] foem[ininum]” (girls).

[28] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 438. “Mushanengi” was the Algonquin name for muskellunge (“muskie”).

[29] Ibid., 438-439; Jonathan Clark Diary, April 20-21, 1784, Mss. A C593a, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky. Muhlenberg records the Continental and State line “lotteries” as having occurred on April 22-23 and April 24, respectively. Clark records attending the “ballot” on April 20 and 21, a two-day discrepancy. A lottery book in the Anderson papers is dated “21 April 1784.”

[30] Muhlenberg to Steuben, April 23, 1784.

[31] “Lottery Book, Falls of Ohio, Lewisville,” April 21, 1784, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 28, p.4, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[32] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:375; Muhlenberg to Steuben, April 23, 1784; Lottery Book, pp.9, 12, 15.

[33] Lottery Book, pp.2, 17, 31.

[34] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 439.

[35] Field v. Slaughter and Others, October 22, 1808, Court of Appeals of Kentucky.

[36] The gentlemen were Col. William Fleming, John Edwards, Col. John Campbell, and Walker Daniel. The officers were Brig. Gen. George Rogers Clark, Lt. Col. John Montgomery, Capt. John Bailey, Capt. Robert Todd, Lt. Abraham Chaplin, and Lt. William Clark (the general’s cousin). James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781, Virginia Series vol. 3 (Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), 413n1.

[37] Robert Todd in Fayette; Walker Daniel in Lincoln; and John Campbell, John Montgomery, and John Bailey in more populous Jefferson County around Louisville. James, ed., Clark Papers, 417.

[38] Clark Grant Board of Commissioners proceedings, 1783-1846, BV2557, p. 1-2, 5, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis.

[39] Clark Grant Commissioners proceedings, 14, 39; William Hayden English, The Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778-1783 and Life of Gen. George Rogers Clark, 2 vols. (Bowen-Merrill Company, 1896), 2:825-860.

[40] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:565. “Lot” in this sentence refers to parcels of land, not to a lottery.

[41] Clark Grant Commissioners proceedings, 25-27; Gwathmey, Virginians in the Revolution, 675.

[42] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 437; Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:416–421.

[43] James Logan to Peter Muhlenberg and George Rogers Clark, April 27, 1784, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 2, pp.24-26, Library of Virginia, Richmond. Punctuation added for clarity.

[44] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 439-440.

[45] Ibid., 439. See also Hening (ed.), Statutes, vol. 10, p.159-160.

[46] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 440.

[47] Ibid., 441-444.

[48] Muhlenberg, Life of General Muhlenberg, 69; “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 446.

[49] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 442.

[50] Ibid., 442-443.

[51] Ibid., 443-444.

[52] Potts, Clark and Croghan, 126.

[53] William Pitt Palmer et al., eds., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (James E. Goode, 1875-1893), 3:607.

[54] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 444-445; Hammon and Taylor, Western War, 51, 109-110, 202.

[55] “General Muhlenberg’s Journal,” 425-427, 445-551.

[56] Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, December 1834 session (Richmond: Thomas Ritchie, 1834 [sic.]), 95-96.

[57] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 34 vols. (Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 17:806-807.

[58] Journal of the House of Delegates, December 1834 session, 96.

[59] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:564-567.

[60] Paul W. Gates, History of Public Land Law Development (Washington: Public Law Land Review Commission, 1968), 59.

[61] Virginia Delegates to Benjamin Harrison, September 8, 1783, Paul H. Smith, et al., eds., Letters of Delegates to Congress: 1774-1789, 26 vols (Washington: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 20:643-633; Ford, ed., Journals of Congress, 25:534 n.2.

[62] James, ed., Clark Papers, 152-153; Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792 (University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 2:657.

[63] “Gen. P. Muhlenberg to His Excellency, the President of Congress,” July 5, 1784, in William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 30 vols. (P.M. Hale, 1886-1905), 17:159-161.

[64] Edmund C. Burnett, ed., Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, 7 vols. (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1921), 7:580.

[65] Burnett, ed., Letters of Congress, 7:579-580.

[66] Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, December 1821 session (Thomas Ritchie, 1821 [sic.]), 220.

[67] Journal of the House of Delegates, December 1834 session, 94.

[68] Hening, ed., Statutes, 11:447-448.

[69] Journal of the House of Delegates, December 1821 session, 220 and December 1834 session, 94.

Recent Articles

Siege: The Canadian Campaign in the American Revolution, 1775-1776

The Sieges of Fort Morris, Georgia

This Week on Dispatches: Scott Syfert on the Mecklenburg Declaration

Recent Comments

"The Sieges of Fort..."

Thank you for the article highlighting our Fort Morris. A few comments...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.