The ten weeks between the American victory at Yorktown and the close of 1781 were a journey from the mountain top to the valley for the Continental army. On the summit, the army’s leaders looked down on the morale-boosting victory they had chased for years, and the successful removal of a British army under Gen. Charles Cornwallis from the equation. The view was, however, short-lived, as only weeks later they found themselves on the valley floor. The army was in perilous condition, faced with serious deficiencies that revealed themselves at a place called Videau’s Bridge in the first week of 1782. By January 1, the evacuation of Cornwallis’s army and the push of remaining British forces from the interior to the coast was complete, but victories in war often face counterattacks, and victories unable to withstand them are meaningless. Everything the Americans had accomplished had to be held to yield permanent results and provide leverage to their peace negotiators in France.

Contemporary participants viewed Yorktown as a positive step toward peace, destined to carry significant weight in the negotiations, but no one viewed it as the end of the war and planning for the next campaign carried on. Gen. George Washington’s intelligence reports told him the British planned to reinforce their southern positions, and on January 3 he wrote to Elias Dayton of a fleet leaving New York harbor bound with reinforcements for Charles Town, South Carolina.[1] The report turned out to be false, but Washington was daily forced to weigh such intelligence and react to possible British movements, keeping him and the northern army occupied full time. Armed conflict between Yorktown and the new year was light, but the lull disintegrated when the calendar rolled into 1782.

In the South, the action began right away. Charles Town was under the command of Cornwallis’s replacement, Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie. His immediate orders were to consolidate and hold British positions. Complicating his mission was an influx of Loyalist refugees, who in the wake of Yorktown faced violent retribution and persecution in a state of lawlessness and civil war as Patriots swept through and solidified their control inland. Through all the challenges, the path to Videau’s Bridge began with the simplest of needs for General Leslie, food. The combination of troops, refugees, and Charles Town’s natives overwhelmed the British army’s food supplies, and as Patriot forces moved closer, the territory available to forage steadily declined. Leslie quickly “began to feel seriously the effects of the restriction of his foraging ground.”[2] The challenge became dire, and the British had reportedly slaughtered nearly 200 horses due to a lack of feed.[3]

Collecting food supplies meant venturing into the interior where conflict was unavoidable, but Leslie had no viable alternative. He caught a possible break in late December, receiving intelligence that the main Patriot force watching his foraging ground, Brig. Gen. Francis Marion’s brigade, had become disorganized, spread thin, and was vulnerable to an attack.[4] A victory over Marion’s forces could push the Patriots back and reopen a vital supply line. Leslie decided on an offensive strategy and ordered an incursion timed with the new year. He dispatched Maj. William Brereton with over 350 men, including a cavalry unit under Maj. John Coffin, into the interior across the Wando River near a British outpost at Hobcaw’s Point. A force of such size was destined to attract attention, purposely providing Leslie with the opportunity to both collect supplies and land a blow on the enemy. It was high risk to say the least, and Leslie’s decision reflects the challenging circumstances. But the potential reward was substantial.

Leslie’s intelligence on the vulnerable state of Marion’s brigade may be understated, as we do not possess the original source, but rather Leslie’s declaration that “Having received such information of General Marian’s situation on the north side of the Cooper as to induce me to detach against him, a party under the command of Major Brereton … was crossed to Daniel’s Island and moved from thence.”[5] What we know with certainty is that the events that followed reveal the fascinating story of a brigade indeed in disarray and suffering from the internal squabbles of its officers, an unfortunate microcosm of the Continental army at large in 1782. The contents of Leslie’s intelligence report would be a treasure for researchers of the post Yorktown era, but there remains ample material to examine the path to Videau’s Bridge and the confrontation that resulted. Both are in need of proper historical analysis, and as the following paragraphs demonstrate, the exercise yields an updated narrative.

Scouts under Patriot Col. Richard Richardson spotted Brereton’s forces shortly after they crossed the river and moved inland on January 2. Richardson quickly informed Marion of the incursion and requested reinforcements to engage the enemy, which Marion obliged by ordering the cavalry of Col. Hezekiah Maham to join with Richardson’s forces immediately.[6] At this juncture the first complication of the engagement surfaced. Maham was an experienced cavalry officer, but since shortly before Yorktown had refused to lead his unit due to a dispute over rank and command structure with another cavalry commander, Col. Peter Horry.[7] Command of Maham’s troops fell to the inexperienced Capt. John Carraway Smith. Adding to the inexperience of command, the unit had a number of post-Yorktown replacements new to the cavalry and untested in combat.

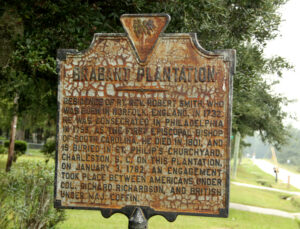

Smith’s orders were to locate the enemy and “charge with vigor-at all hazards” any cavalry he encountered as long as their infantry was not a threat, and then send word to Marion so he could bring up the full strength of the brigade’s infantry.[8] Their immediate infantry support, Richardson’s unit, was largely made up of former Loyalists who had taken the recent offer of clemency from South Carolina Gov. John Rutledge on the condition they joined the South Carolina militia for six months. The inexperienced cavalry and the makeshift infantry came together the morning of January 3. That afternoon they came across British troops resting at a plantation named Brabant owned by a Rev. Robert Smith. The British had positioned themselves well, protecting the approaches to their position with a swamp to one side and a causeway with a bridge on the other. While the British had set themselves up well defensively, the American commanders began a series of tactical errors.

The militia went undetected by the resting British troops and Richardson, rather than attacking the position immediately, executed a flanking maneuver to swing around and approach the British position from the north. As they did so the Americans passed an ideal position upon a small ridgeline, complete with trees, a fence line, and a ditch they could have occupied and waited for the British to pass through.[9] Instead, Richardson moved his troops beyond the ridge line and to the bottom of its embankment area, stationing them in a frontal position to the British. He then left the unit to move toward the British position and conduct his own reconnaissance run before commencing an attack. The British cavalry’s vanguard under Capt. Archibald Campbell spotted Richardson a short distance from their camp and gave immediate chase.

Richardson turned, rode hard back to his men, and arrived with British cavalry in hot pursuit. He had just enough time to order Captain Smith to mount his cavalry and charge the British pursuing him. Impressively, the inexperienced unit mounted quickly and engaged the enemy well enough to not only halt their charge, but to turn them around and send them riding hard back toward their camp. It would be the Patriot high water mark, as from there the unit’s inexperience steadily emerged. As the British cavalry retreated to their lines American horsemen charged headlong after them without hesitation. No one recorded that Captain Smith or Colonel Richardson tried to stop them. The element of surprise had clearly been lost, and British infantry had been given a precious few minutes to prepare, plenty for a well-trained professional unit. The American cavalry was running full speed into a disaster, and in the confusion and fog of battle no one called a halt.

When everyone arrived back at the British position it turned deadly for the Americans. The British cavalry crossed the bridge safely and put the creek between themselves and the pursuing Americans who never slowed. The Americans met a well-timed volley of fire from the British infantry, and several Patriots were killed. The British cavalry took the opportunity to join with the balance of their mounted colleagues, and all British forces converged on their side of the bridge. They now had a combined infantry and cavalry unit at arms and in control of the battlefield. In only minutes the Americans had been drawn into a fight they were neither prepared nor well-positioned for. Even their path for retreat was complicated. As one historian described the scene, “All was at once in confusion, horses and men wedged together upon a narrow causeway, the front striving to retreat and the rear pushing them on.”[10]

The British cavalry took full advantage of the American confusion and attacked, wreaking chaos throughout the American ranks. The American inexperience manifested fully as “The recruits, terror-stricken and having not the slightest idea which way to turn, suffered heavily and were even ridden down by some of the more experienced Patriots trying to get out of the melee.”[11] Several experienced American officers rallied a few men well enough to prevent the unit’s complete destruction, but by and large American troops scattered in every direction. The Royal Gazette in Charles Town reported that British cavalry chased several groups of panicked Patriots for up to six miles before giving up their pursuit, adding insult to injury and embarrassment for the Americans who suffered a rout that came uncomfortably close to a massacre.[12]

Variation in casualty numbers are of course common in many wars, the Revolutionary War especially, and Videau’s Creek incredibly so. A detailed review of the historiography in chronological order permits some clarity on the casualty question. The first secondary work on the battle, William Dobein James’s Sketch of a Life of Francis Marion published in 1821, claimed “Twenty-two Americans were buried on the causeway; how many were killed in the pursuit is not known. Of the British, Capt. Campbell was killed, and several of his men, but the number was not ascertained.”[13] James provides no source for his claim of twenty-two dead, and this author has been unable to locate a primary source that supports the number. James served under Marion at times during the war and his father was also close to Marion. He collected oral histories from veterans and civilian witnesses in addition to his own recollections. As he described it, “I became an eyewitness of the scenes hereafter described; and what I did not see, I often heard from others in whom confidence could be placed.”[14] Perhaps he took the number from a lost newspaper article, or an oral history interview he conducted.

Author W. Gilmore Simms in his work The Life of Francis Marion, released in 1844, repeats the numbers but admits in his preface that James was the source for nearly all his material.[15] South Carolina politician and amateur historian Edward McCrady covered the battle in his work The History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1780-1783, but as his description is a mirror image of James, the source of his number of twenty-two killed is obvious. In Charles Town, Loyalist newspaper The Royal Gazette listed fifty-seven Patriots killed in its January 5 edition and then upped the figure to over ninety just four days later. These numbers are clearly suspect and inflated, part of the era’s partisan propaganda wars, and are nowhere near the figures exchanged in primary sources, nor any other secondary source. Such a number would have equaled nearly a 25 percent casualty rate for the Americans, and it stands to reason such a loss would have somehow made its way to General Washington in writing. A review of Washington’s papers reveals no word of the Videau’s Bridge affair was sent to him, and no reports on the battle went beyond Gen. Nathanael Greene in the chain of command. Modern works mentioning Videau’s Bridge have stuck with the oft repeated twenty-two killed and numerous others wounded and missing. They do not appear to have scrutinized the figures of the early authors against primary sources.

The main primary sources are Marion’s letters to Nathanael Greene and the orderly book of Maham’s unit. Sorting Marion’s after-action reports chronologically as he gathered information and updated Greene seems to clear up much of the confusion. His first report to Greene was on January 5, and he broke out the report between Continentals and militia, relaying that “Our loss at this time cannot well be ascertained” but that it appears “not more than five or six killed, wounded, and missing, and about as many of the militia.”[16] This would place the total at around twelve or so total casualties. Marion’s letter, however, hedges his numbers at several points, with two instances in the letter where he confusingly tells Greene that missing men have arrived, writing of “scattered men who are coming in hourly.”[17] As one reads through the letter it is natural to think that perhaps he should have stopped with “Our losses cannot well be ascertained at this time.”

The next source to examine is the orderly book of Maham’s unit, which contains a report dated January 8, listing the casualties for their corps as five killed, two wounded, and three captured.[18] This seems a reasonable fit, as the final source comes just over a week later when Marion had time to gather information and take account of men who had fled the field in such a panic as to separate themselves from the army for a short time and confuse the ability to accurately determine losses. In a letter to Greene on January 15, Marion seems to have had a better grasp of the battle’s events, admitting the action was “much greater” than he first believed.[19] He now listed casualties as six killed, nine wounded, and fifteen missing. It is possible some or many of the missing returned later. Marion also reported twenty-nine horses as missing. Some of the missing men may have become separated from their horses, delaying their return to the army. In the end Patriot casualties cannot be accurately decided, but were likely much less than the twenty-two killed typically reported by secondary sources.

British casualties were listed by Leslie as one killed and two wounded in his letter to Gen. Henry Clinton at the end of January, but this seems improbable. Individual accounts of Patriots fighting their way out of the crowded melee with the British cavalry at the bridge by slashing with swords and firing pistols are numerous in the early sources. These combine with similar accounts of the successful initial charge by Smith’s cavalry on the British group pursuing Richardson. Marion mentioned several British casualties from that moment in his initial report to Greene on January 5. Enough sources exist to indicate that British casualties were likely more than the three claimed by Leslie. Marion reported them as four killed, fourteen wounded, and one prisoner taken. Those numbers align with the primary accounts and evidence more closely than Leslie’s. It is no stretch to believe that in the shadow of victory Leslie was not concerned with relaying accurate numbers to Clinton on a matter closed weeks prior for an operation that yielded its intended effect.

The final analysis of Videau’s Bridge is not about the inadequate historiography and confusing casualty figures. The post-Yorktown situation for the Continental army and the attached militia units was filled with challenges and marred by self-inflicted failures. Videau’s Bridge opened 1782 and demonstrated both. The dispute between Colonels Maham and Horry proved costly. Maham was an experienced cavalry officer and his absence clearly disadvantaged Patriot forces. The limited historiography has well noted the effect of Maham’s absence, but not the cause. Maham was not on leave, or ill, or away on important military business when the fight took place. He was in the same vicinity as Marion and others who either participated in the battle or were on their way to do so. Maham was in a fit of insubordination, refusing to lead his men due to the ongoing dispute over his rank in relation to that of Colonel Horry.

Maham’s refusal, a personal choice, has not been given the weight it deserves in analysis of the confrontation. Near the end of February, the Americans would suffer another defeat at a place called Wambaw Creek, where again the cavalry’s failure was a leading factor in the loss, once more Maham’s corps, once more without Maham. The limited historiography of that confrontation consistently notes Maham’s absence as due to insubordination over the issue of his rank, something that began much earlier. The dispute between Maham and the army began in the summer of 1781 and evolved from there.[20] By January Maham had made numerous complaints, requests or declarations about the affair, and several pieces of evidence demonstrate the importance of the issue during the week of Videau’s Bridge. On January 4, as his corps must have been staggering back from their loss at the bridge, Maham wrote to Greene asking that his corps be not only under his sole command, but that it be considered “independent” and answerable only to Greene.[21] On January 8, at General Marion’s request, both Horry and Maham reported to his headquarters to make their case on the rank issue personally.[22] The evidence proves that for Videau’s Bridge Maham was in the area, available, aware of the situation, and chose not to serve with his men, leaving them filled with inexperienced officers and new recruits.

Additionally, important to the analysis of Videau’s is a piece of evidence previously overlooked. On December 15 Governor Rutledge wrote to Marion and asked that “an escort of twenty-five men, and a proper officer from Maham’s corps” be sent to him before December 31 to escort him to Greene’s camp for business and then on to the opening of the new state legislature session in Jacksonborough.[23] The men were dispatched, confirmed by both Marion and Maham mentioning their absence in early letters to Greene within two days of the loss at Videau’s, complaining the men were “now much wanted here.”[24] The officer sent is not mentioned, but the timing of their complaints to Greene was clearly influenced by the cavalry’s embarrassment. The absence of these men from the Videau’s Bridge action doubtlessly hurt the Patriot effort and stands as further reason Maham’s leadership was needed. His failure to put the needs of the larger war effort over his own priorities was counterproductive, but such issues were not unheard of in the Continental army during 1782.

Finally, Richardson’s tactical decisions were costly. Richardson was ultimately the officer in charge and failed to control the cavalry’s movements, allowing them to precipitate an irresponsible chase of the British and separate themselves from the assistance of their infantry. He failed to account for the inexperience of his cavalry, particularly the officers. These factors were well known to Richardson, and he should have managed the unit more closely. He was to engage only cavalry and then send his position to Marion so the full brigade could be brought up, yet he took steps that permitted a full engagement. He also failed to position his men well and use the ground he held to his advantage. Rather than waiting for the British to come to him in a position of strength, he poorly positioned his men and then allowed himself to personally be spotted by British cavalry, setting off the chain of events that saw a bulk of Marion’s brigade overrun and scattered from the field of battle.

The battle was consequential. The Continental army began the year with an embarrassing loss that drove them from the field of battle in a panic and validated the intelligence Leslie held that Marion’s army was weak and disorganized. Infighting among the army’s command structure yielded negative results on the battlefield and further weakened Marion’s army. The British successfully foraged for needed supplies, and months after the Yorktown victory the Continental army and its militia units proved once more incapable of facing any type of British-led troops in the field. Finally, Marion wrote to Greene that “The want of ammunition will also prevent me from making the opposition I ought to do.”[25] A mere ten weeks from their greatest victory the Continental army was back to the suffering of embarrassing defeats, wanton lack of supplies, and infighting among their officers. Videau’s Bridge was the first of several such losses of 1782, and the path to peace after Yorktown must have seemed as far away as ever for some of the Patriots on the ground in South Carolina during those first few days of a new year that many hoped would be the war’s last.

[1] George Washington to Elias Dayton, January 3, 1782, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07638.

[2] Edward McCrady, The History of South Carolina in the Revolution, vol. 4 (New York: The McMillan Company, 1902), 589.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The report of this intelligence was passed on after the battle via Alexander Leslie to Sir Henry Clinton, January 29, 1782, contained in The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:162. Analysis and commentary on the leadup to Videau’s Bridge provided by the editor of Greene’s papers, Dennis M. Conrad.

[5] Alexander Leslie to Henry Clinton, January 29, 1782. Report On American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Vol. 2 (Dublin: John Falconer, 1906), 389.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See Peter Horry to Nathanael Greene, January 12, 1782, in The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:189n1-4 for a detailed examination of the dispute between Maham and Horry, complete with correspondence and annotations.

[8] Original letter is in Mahan’s orderly book in the New York Public Library, quoted here from The Papers of Nathaneal Greene, 10:162.

[9] William Dobein James, Swamp Fox: General Francis Marion and His Guerrilla Fighters of the American Revolutionary War (1821; repr., United States, 2013), 89.

[10] Ibid, 89.

[11] Warren Ripley, Battleground: South Carolina in the Revolution (Charleston: Post-Courier Books, 1983), 214.

[12] The Royal Gazette, Charles Town, South Carolina, January 5, 1782.

[13] William Dobein James, Swamp Fox: General Francis Marion and His Guerrilla Fighters Of The American Revolutionary War (Charleston: n.p., reprinted in 2023), 90. This title was originally published under the title of William Dobein James, A Sketch of the Life of Brigadier General Francis Marion and a History of his Brigade: From its Rise in June 1780, Until Disbanded in December 1782 (1821). Both texts are the same with only a title change made to the modern reprint of the text.

[14] Ibid, 4.

[15] W. Gilmore Simms, The Life of Francis Marion (1844).

[16] Marion to Greene, January 5, 1782, Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:161.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid, 10:163n5.

[19] Marion to Greene, January 15, 1782, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:196.

[20] See Greene to Horry, July 30, 1781, Papers of Nathanael Greene, 9:107.

[21] Hezekiah Maham to Greene, January 4, 1782, Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:158.

[22] Marion to Greene, January 15, 1782, Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:197n5.

[23] John Rutledge to Marion, December 15, 1781, The Documentary History of The American Revolution, ed. Robert W. Gibbes (Columbia, SC: Banner-Steam Power Press, 1853), 224.

[24] Maham to Greene, January 4, 1782, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:158, and Marion to Greene, January 5, 1782, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:162.

[25] Marion to Greene, January 5, 1782, Papers of Nathanael Greene, 10:161.

Recent Articles

The American Princeps Civitatis: Precedent and Protocol in the Washingtonian Republic

Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia

The Course of Human Events

Recent Comments

"General Israel Putnam: Reputation..."

Gene, see John Bell’s exhaustive Analysis, “Who Said ‘Don’t Fire Till You...

"The Deadliest Seconds of..."

Ed, yes Matlack's son was reportedly a midshipman on the Randolph. That...

"The Whale-boat Men of..."

From my research the British Navy kept a very regular schedule across...