There is a fine line between courage and stupidity. Eight men congregated at Smithfield Plantation in southwest Virginia on April 7, 1774, prepared for a perilous adventure. They were young men in high spirits, ready to set off into Virginia’s mostly unexplored western wilderness. Their intrepid leader was Deputy Fincastle County Surveyor John Floyd. Their guide was the original longhunter, James Knox, who knew the terrain.[1] A separate eight-man team led by Deputy Surveyor Hancock Taylor had already left. Their task was to survey lands that had been promised to veterans of the French and Indian War twenty years before as a reward for their service. Now, however, the Old Dominion was on the verge of a new war with the Shawnee and Mingo tribes. Crossing the Alleghenies at this moment was reckless; some of the expedition’s members would never be seen again.[2]

Many of the surveys had already been conducted, which added to the madness. Thomas Bullitt led an expedition down the Ohio River from Fort Pitt in 1773, marking off lots for veterans of the old war or men who had bought their warrants.[3] When Bullitt finished, Fincastle County refused to accept his plats. The surveys had not been done by county surveyors, as was required by law, and some of them encroached on unceded Cherokee land. So, despite the danger, Fincastle Surveyor William Preston was sending his own men out now to do the job correctly.[4]

Floyd’s team followed the New River north-northwest into the beauty of what is now New River Gorge National Park. They met Taylor’s team where the New joined the Gauley to form the Great Kanawha River. They continued on foot until they passed the river’s falls, then traveled in canoes made on site. Fincastle County was vast, stretching all the way to the Mississippi River and encompassing what are now southwest Virginia, southern West Virginia, and all of Kentucky. The sixteen Virginia men made their first surveys for Col. George Washington along the Kanawha, floated north to the river’s mouth, and continued their work along the left bank of the Ohio River and its north-flowing tributaries.[5]

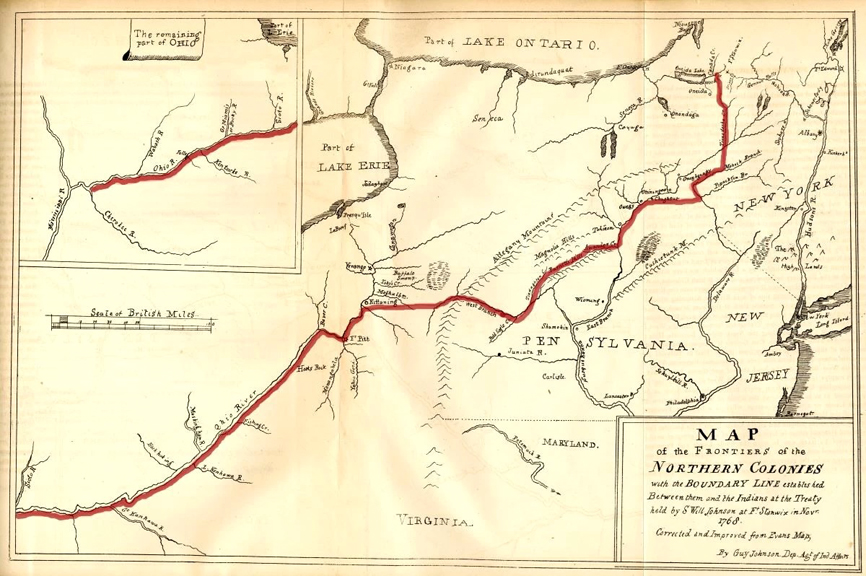

The danger increased while they worked. The Cherokee and the Six Nations Confederacy of Iroquois tribes (the Haudenosaunee) had sold this land to Virginia and North Carolina in 1768 and 1770. Though nominally under Haudenosaunee authority, the Shawnee and Mingo rejected those agreements, and Captain Bullitt’s abrasive conduct the previous year had further strained relations. Floyd and Taylor encountered hunters and settlers fleeing east, as well as a few individuals who were foolishly determined to stay. Others, seeking safety in numbers, asked if they could join the surveyors. The Shawnee, the explorers learned, “had placed themselves on both sides of the [Ohio] river, and … intended war.” Floyd tried to hire a fleeing man who could speak Algonquian as a hedge against trouble. The man “refused,” a team member noted, “and told us to take care of our scalps.” Undeterred, the Virginians continued down the river, surveying more land for prominent men such as Patrick Henry and Hugh Mercer.[6]

The tension burst into a war when several Mingo were murdered on the upper curve of the Ohio, northwest of Fort Pitt.[7] Although news of the atrocity reached the surveyors, Floyd and Hancock were determined to continue their work. But acrimony followed dissent, and men began to disappear.[8] Back at Smithfield, Colonel Preston grew concerned and sent Daniel Boone and Michael Stoner to find his surveyors.[9] James Knox made his own way back, escorting the original settlers of Kentucky’s first town, Harrodsburg.[10] Floyd also made it out, but Hancock Taylor, the uncle of an American president, was among those never seen again.[11]

Virginia’s Western Land

There were no banks or stock markets in colonial America. Even precious-metal coinage, called “specie,” was rare. Land was the only obtainable form of durable wealth, and demand for it was therefore immense. A hundred acres of good land was considered enough for a once-poor man to become self-sufficient. The military bounty land Floyd and Taylor surveyed in 1774 was first promised in 1754, when Gov. Robert Dinwiddie announced that 200,000 acres on the south side of the Ohio would be granted to the officers and men of the Virginia Regiment raised for service in the French and Indian War.[12]

Those parcels were just tiny dots in the enormous expanse of land granted to Virginia by King James I in its charter. Early Jamestown leader John Smith tried to explain the vastness of the colony in 1616: “Virginia is no ile (as many doe imagine) but part of the Continent adioyning to Florida; whose bounds may be stretched to the magnitude thereof without offence to any Christian inhabitant.”[13] As initially conceived, Virginia’s northern border would have stretched to the Alaska coast opposite Russia. Robert Beverley boasted in his 1705 history that Virginia “was a Name at first given, to all the Northern Part of the Continent of America,” and the names of other colonies “for a long time served only to distinguish them, as so many parts of Virginia.”[14] The president of the College of William and Mary teased in 2016, “Some like Maryland, the Carolinas, Kentucky and West Virginia acknowledge their ancestry. Other states are more reluctant to acknowledge from whence they sprang.”[15] Notable in the latter group is Massachusetts, which has often portrayed the Mayflower’s landing as America’s origin story. But these colonies were all stacked along the Atlantic coast. In the West, the Old Dominion’s claims were limited only by Spanish control and a few competing colonial claims. Alaska was never realistic, but eastern Minnesota was. The North Carolina line was surveyed in 1779. The First Colony governed Pittsburgh until 1780, when the current state border with Pennsylvania was agreed to. Even then, everything above North Carolina (which included Tennessee), south of the Great Lakes, and west of Pennsylvania to the Mississippi belonged to Virginia.[16]

There were four types of land possession in colonial America: sovereignty (held by the monarch), charter territory (a colony’s designated extent), occupancy (by Indians or settlers, according to treaty), and title (individual ownership of real estate). They did not always align. Sovereignty under European convention was established through discovery or conquest and ultimately defended by military power. Charters were granted by the Crown. British practice was to leave the right of occupancy in the hands of the Natives by default, while acquiring land through purchases and treaties.[17] The first of these treaties was made in 1646.[18]

It was illegal to settle on land not so acquired, but individuals sometimes violated the law. The law implementing the 1646 treaty made this a felony.[19] The injustices associated with private purchases of Indian land were likewise recognized early on and banned by Virginia in 1658 and 1705 and by royal proclamation in 1763.[20] Pennsylvania went so far as to establish “death without the benefit of clergy” as the punishment for western squatters who refused to vacate.[21] After the colonies declared independence, in 1779 Virginia specifically banned settlement north of the Ohio River and authorized the use of military force to expel trespassers.[22] Congress did the same in 1783.[23] Few of these measures were effective for long.

The treaties that opened Kentucky to settlement also set the Ohio River as the outer limit of white settlement. As boundaries go, it was excellent. There was certainly no mistaking where it was, but there were serious problems. The villages of the Shawnee, Mingo, and Delaware were on the north side of the river, but they used Kentucky for hunting and resented the Haudenosaunee’s sale of the land. The conflict that took Hancock Taylor’s life is known as “Lord Dunmore’s War,” after Virginia’s last royal governor. It ended with an armistice negotiated at Camp Charlotte in Ohio late in the fall of 1774.

The armistice made Kentucky safer for settlement just five months before the Revolutionary War began. When the first Virginians marched north to face the Redcoats at Boston under captains Daniel Morgan and Hugh Stephenson, many others were traveling west in search of new chances to prosper.

The Bounty Land System

In 1778, after proposing the secret expedition to Gov. Patrick Henry, George Rogers Clark daringly captured the previously French settlements of Kaskaskia and Cahokia along the Mississippi River in what is now Illinois. Still more impressive was the capture of Vincennes along with British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, who normally operated out of Detroit.[24] Clark’s volunteers were asked after the capture of Kaskaskia to enlist in a new unit called the Illinois Regiment.[25] Before Clark set out, Assembly members Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and George Wythe promised in a letter, “we have no doubt but some further reward in Lands in the Country will be given to the Volunteers who shall engage in this Service in addition to the usual pay if they are so fortunate to succeed.” More specifically, they suggested, “We think it just & reasonable that each Volunteer entering as a common soldier in this expedition, should be allowed three hundred acres of Land & the officers in the usual proportion, out of the Lands which may be conquered.”[26] This was a promise that applied to a discrete group of volunteers who were taking on a particularly difficult mission. But Governor Dinwiddie had set a precedent, and land was the only thing of real value Virginia had to offer its soldiers. Further awards were inevitable.

Volunteers had to be turned away at the start of the Revolution, but recruiting and retention became increasingly difficult as the war progressed. In 1779, the Commonwealth began offering increased inducements, including 100 acres of land, to enlisted men who served “during the continuance of the present war.” This was later expanded to offer 100 acres to Virginians who enlisted in the State or Continental lines and served for three years, and double if they enlisted for (and served to) the end of the war. Field and company officers received much larger allotments but had to serve the duration.[27]

The Commonwealth decided in 1780 to award 15,000 acres to each of its major generals, 10,000 acres to its brigadier generals, and an additional one-third over the previously established awards to field and company officers. In 1782, the state awarded each long-serving veteran “one sixth part in addition to the quantity of the land apportioned to his rank” for each full year above six that he served. Because the war lasted eight years it was possible, therefore, to obtain an extra two-sixths, but few men qualified. In a special award, the Commonwealth made Friedrich Wilhelm, Baron de Steuben, eligible for a major general’s share.[28] Though a Virginian, the commander-in-chief was awarded no land for service in the Revolution.

Standard Bounty Land Acreages for Virginia Veterans

| Rank | 3 Years | End of War |

| Soldier or sailor | 100 | 200 |

| NCO | 200 | 400 |

| Subaltern | None | 2,000 + 666⅔ |

| Captain | None | 3,000 + 1,000 |

| Major | None | 4,000 + 1,333⅓ |

| Lt. Colonel | None | 4,500 + 1,500 |

| Colonel | None | 5,000 + 1,666⅔ |

| Brig. General | None | 10,000 |

| Maj. General | None | 15,000 |

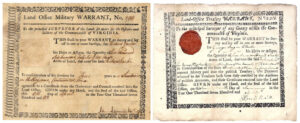

Virginia also made “waste or unappropriated lands” available to anyone for £40 per hundred acres, payable to the Virginia Treasury. Thus, there were two kinds of warrants: military warrants and treasury warrants. The warrants authorized a licensed surveyor to measure out a specific plat. Though warrant holders could technically acquire any treaty-acquired, undeeded land in Virginia, all the available good land was in the west.[29] Each claimant was required to participate in the survey, bringing his own chain carrier and marker if necessary. Like Fincastle’s William Preston, surveyors were county employees nominated, examined, and certified by the College of William and Mary, which took a percentage of their fees. The college also licensed deputies like John Floyd and Hancock Taylor.

As anticipated by many who had gone west, Virginia retroactively allowed “actual settlers” to buy 400 acres of the land they occupied at very low prices and to purchase another 1,000 acres at reduced rates. These claims were given priority, “preempting” any others. Preemption warrants were limited to one per person, but land jobbers gamed the system by carving the initials of friends or family members into the trees marking their claims.[30] Land not acquired by treaty was off limits. The law stipulated that “No entry or location of land shall be admitted within the county and limits of the Cherokee Indians, or on the north west side of the Ohio river.” Trespassers on Native land were to be forcibly removed. To the advantage of preemption claimants, treasury warrants could not be surveyed until a year after the statute was enacted, or May 1780.[31]

To receive land after the war’s end, a commissioned officer (or his heirs) first had to acquire a written certification of sufficient service “from any general officer of the Virginia line, or the commanding officer of the troops on the Virginia establishment as the case may be.” A common soldier could receive his certificate from his regiment’s colonel or commanding officer. The grantee then had to appear in any Virginia court and attest to his own service under oath. The clerk of the court endorsed the certificate, recorded it in his own records, and sent a list of all recorded certificates to the Land Office in Richmond each October. The warrants issued by the Land Office entitled the bearer to have a survey made. When that was done, the governor issued “deed polls” or “patents,” granting title to the land.[32] Many veterans were unable to navigate this cumbersome and lengthy process.

The Bounty Land Reserves

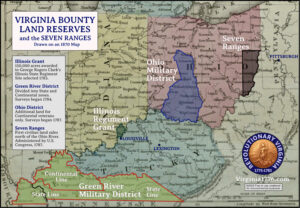

Virginia designated three districts of western land for its discharged warriors. The Green River District in Kentucky was to be shared by the Commonwealth’s State and Continental lines. State troops, called Provincials before independence, were under the command of the governor and intended for service protecting the Commonwealth. Given that Virginia had to defend its western expanses virtually alone, the State Line contributed significantly to the Old Dominion’s war efforts. Set aside in 1779, the Green River District included “all the lands between the Green river and the Tenissee river, from the Allaghany mountains to the Ohio river.”[33] It covered about three-sevenths of what became the Commonwealth of Kentucky, encompassing an estimated 6 million acres.[34] The Cumberland River ran through the eastern part of the district, and “land on Cumberland” was sometimes used as shorthand for military land in the early days. Later, a second reserve of more than 4.2 million acres was created in Ohio for the larger Continental Line. Lots in the Ohio Military District were to be distributed when no quality Green River District land remained.[35] The Ohio land was bounded by the Sciota and Little Miami rivers, and “land on Sciota” was a common shorthand. In 1781, the General Assembly awarded Clark’s men 150,000 acres “in such place on the north west side of the Ohio as the majority of the officers shall choose,” to be divided by “fair and equal lot among the claimants.” This territory was known as the Illinois Grant, though it is now in the State of Indiana.[36]

Virginia designated three districts of western land for its discharged warriors. The Green River District in Kentucky was to be shared by the Commonwealth’s State and Continental lines. State troops, called Provincials before independence, were under the command of the governor and intended for service protecting the Commonwealth. Given that Virginia had to defend its western expanses virtually alone, the State Line contributed significantly to the Old Dominion’s war efforts. Set aside in 1779, the Green River District included “all the lands between the Green river and the Tenissee river, from the Allaghany mountains to the Ohio river.”[33] It covered about three-sevenths of what became the Commonwealth of Kentucky, encompassing an estimated 6 million acres.[34] The Cumberland River ran through the eastern part of the district, and “land on Cumberland” was sometimes used as shorthand for military land in the early days. Later, a second reserve of more than 4.2 million acres was created in Ohio for the larger Continental Line. Lots in the Ohio Military District were to be distributed when no quality Green River District land remained.[35] The Ohio land was bounded by the Sciota and Little Miami rivers, and “land on Sciota” was a common shorthand. In 1781, the General Assembly awarded Clark’s men 150,000 acres “in such place on the north west side of the Ohio as the majority of the officers shall choose,” to be divided by “fair and equal lot among the claimants.” This territory was known as the Illinois Grant, though it is now in the State of Indiana.[36]

Clark’s Men Convene

Major combat ended in the east after Yorktown but continued in the west through the Battle of Blue Licks in August 1782. Six months later, the officers of the Illinois Regiment met at Dutch Station near Louisville to “adopt some mode of having the Land promised them in the Illinois Country ascertained and laid off.” They elected General Clark their chairman and appointed Walker Daniel, the Commonwealth attorney for the Kentucky Judicial District, their administrative agent, to be compensated with a major’s share of land.[37]

They chose five of their number to act as deputies, three making a quorum, to oversee Daniel’s work, hire surveyors, and petition the Virginia General Assembly to incorporate a town in the land they selected. The deputies were General Clark, Lt. Col. John Montgomery, Capt. William Shannon, Lt. William Clark (the general’s first cousin), and Capt. John Bailey.[38] After limited exploration, they claimed land directly across the Ohio from Louisville. They tasked Daniel with drawing up a petition to the Assembly in Richmond “praying an Explination” of the 1781 law, so they could proceed to distribute the land.[39]

The General Assembly gamely responded in October with a statute formalizing the selected land, the town, and appointing a new set of ten commissioners. The Assembly instructed them to “govern themselves by the allowances made by [Virginia] law to the officers and soldiers in the Continental Army.”[40] Henry, Jefferson, Mason, and Wythe had intended the awards to Clark’s men to be especially generous. By not doing the math, however, the legislature ensured, in law, that veterans of the Illinois Regiment would, in fact, receive less from Virginia than other soldiers did.

The State and Continental Lines

Under pressure from its veterans, the Old Dominion moved to quickly distribute military bounty land. It had already required veterans to submit their claims by January 1, 1783 (June 1 for those living out of state).[41] However, the war with the Indians (the Revolution’s western front) remained unresolved, and negotiations were underway to cede Virginia land north of the Ohio to Congress. With so much going on at once, post-war land administration was going to be complicated and dangerous.

In Old Virginia, Lt. Col. Richard Clough Anderson and General Clark were put forward by their comrades to be principal surveyors for the Continental and State lines. Their first task was hiring the deputies who would fan out across southwest Kentucky with chains and compasses to take most of the actual measurements. Anderson received recommendations from Abraham Hite, Jr., and Joseph Neville, both of Hampshire County (now West Virginia).[42] “I wish our mountaineers may all of them answer your expectations,” Hite wrote, adding, “If my business will possibly admit my spending as much time, I am determined to be with you when you get to surveying.”[43] James Wood of Winchester, Frederick County, also recommended some candidates. “Colo. Wood is good enough to mention Lieut. [John] Heth and myself to you by letter which you will receive with this,” wrote former artillery lieutenant Elias Langham. “We are desirous to be of your party whenever the Lands are laid out for the Military Line.”[44]

The officers had gotten ahead of the legislature, but Virginia formalized the processes for the Continental and State lines in November. It appointed “deputations” of officers for the two categories of veterans. The twelve members of the Continental deputation were Maj. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg, Maj. Gen. Charles Scott, Maj. Gen. George Weedon, Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, Brig. Gen. James Wood, Col. William Heth, Lt. Col. Oliver Towles, Lt. Col. Samuel Hopkins, Lt. Col. Jonathan Clark, Lt. Col. Benjamin Temple, Capt. Nathaniel Burwell, and Capt. Mayo Carrington. The members of the State deputation were Gen. George Rogers Clark, Col. William Brent,[45] Col. George Muter, Col. Charles Dabney, Major Thomas Meriwether, Capt. Christopher Roane, Capt. John Rogers, and Capt. Machen Boswell. The deputations were directed to “appoint superintendants on behalf of the respective lines, or jointly, for the purpose of regulating the surveying” of the bounty lands, and to appoint principal surveyors (Anderson and Clark) for each line. Any five officers from the Continental deputation were sufficient to conduct business. Three members of the eight-officer State deputation were enough to make decisions.[46]

A joint meeting of the deputations was held in Richmond on December 17. The Continental officers formally elected Anderson as their principal surveyor, and the State officers chose Clark.[47] With Illinois Regiment responsibilities competing for his time and attention, Clark chose Continental veteran Maj. William Croghan as his chief deputy. The deputations also agreed to divide the Green River District into two zones. This would prevent the Continental and State surveyors from interfering with each other.[48] They decided

that a due south line shall be run from the mouth of Cumberland River twenty miles—thence a due east line, crossing Cumberland river, until it shall intersect the main Green or Barren River; that all the country bounded by the Cumberland river, the said East line, the great Barren, Green, and Ohio Rivers, shall be appropriated to the bounties of the Continental Line, as far as the same shall go—and that all the remaining part of the said tract of country on the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers, as described by the several acts of assembly, shall be appropriated to the bounties of the said state line.[49]

Part of the original Green River District had been lost to North Carolina when the state line was surveyed in 1779. To compensate, the Commonwealth had added land between the Tennessee River and the Mississippi.[50] According to William Croghan, the entire district encompassed six million acres. Most of it was not expected to be surveyed for Virginia’s veterans, who were only expected to accept “good” land. Two-thirds of the land was assessed to be “Barren and lands unfit for cultivation.” The State zone was larger, nearly three and a half million acres, while the Continental zone included about two and a half million acres.[51] This confirms that the deputations knew Virginia intended to hold back some Ohio land for Continental veterans.

Land-rich but cash-poor, Virginia did its best to use the one resource it had to do justice to its veterans while ceding most of its western land to help the thirteen confederated states pay off their war debts. Though Clark and others had successfully put force behind Virginia’s claim to the west, many factors were out of the Commonwealth’s control. The vastness of the territory, a flood of westward-bound veterans, Native resistance to expanded settlement, and British refusal to vacate forts along the Great Lakes soon put the newly independent states on the brink of another war.

[1] Notes regarding long hunters, Draper Manuscripts Collection, C, 5:42–45, Wisconsin Historical Society; Humphrey Marshall, The History of Kentucky (George S. Robinson, 1824), pp.7–9.

[2] Thomas Hanson, “Thomas Hanson’s Journal,” in Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg (eds), Documentary History of Dunmore’s War, 1774 (State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1905), 110-133.

[3] Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), December 3, 1772; Jack M. Sosin, “The British Indian Department and Dunmore’s War,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 74, no. 1 (1966), 42.

[4] W.W. Abbot et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (University Press of Virginia, 1983-1995), 10:70-71; Neal O. Hammon, “Land Acquisition on the Kentucky Frontier,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 78, no. 4 (1980), 297-321; Neal Hammon and Richard Taylor, Virginia’s Western War, 1775-1786 (Stackpole Books, 2002), xvii.

[5] “Hanson’s Journal,” 110-111; William Cecil Pendleton, History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia: 1748-1920 (W.C. Hill, 1920), 225-260.

[6] “Hanson’s Journal,” 113-114, 117-121.

[7] “Hanson’s Journal,” 119; Glenn F. Williams, Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Westholme, 2012), 71-72.

[8] “Hanson’s Journal,” 124-126, Hammon and Taylor, Virginia’s Western War, xxii-xxiii.

[9] Thwaites and Kellogg, Documentary History of Dunmore’s War, 49-51.

[10] “Hanson’s Journal,” 127; Neal O. Hammon, “Land Acquisition,” 302; Hammon and Taylor, Virginia’s Western War, xxvi-xxix.

[11] American Archives, ser. 4, 1:707; Thwaites and Kellogg, Documentary History of Dunmore’s War, 23, 164, 172-173.

[12] William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes At Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, 13 vols. (various publishers, 1821-1823), 7:661-662.

[13] John Smith, A Description of New England (London: Humfrey Lownes, 1616), 3.

[14] Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia, 4 vols (London: R. Parker, 1705), vol. 2, pp.1-2.

[15] Taylor Reveley, “In the beginning was Virginia, and Virginia led,” Commemorative Session of the Virginia General Assembly, January 30, 2016, www.wm.edu/news/stories/2016/in-the-beginning-was-virginia%2C-and-virginia-led.php.

[16] Some of the north parts of this territory intersected with the noncontiguous charter land extensions of Massachusetts and Connecticut.

[17] Paul W. Gates, History of Public Land Law Development (Washington, DC: Public Law Land Review Commission, 1968), 1

[18] Hening, ed., Statutes, 1:323-326.

[19] Ibid., 1:324.

[20] Gates, History of Public Land Law, 33-34.

[21] James T. Mitchell and Henry Flanders, eds., The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801, 18 vols. (Harrisburg: Clarence M. Busch, 1896-1915), 7:153.

[22] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:40, 179.

[23] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 34 vols. (Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 25:602, 694.

[24] William Hayden English, The Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778-1783 and Life of Gen. George Rogers Clark, 2 vols. (Bowen-Merrill Company, 1896), 1:88. Vincennes is now in Indiana, immediately opposite Illinois on the Wabash River.

[25] Clark Grant Board of Commissioners proceedings, 1783-1846, BV2557, Historical Society of Indiana, 2-3.

[26] English, Conquest of the Northwest, 1:96-97; Cynthia Miller Leonard (ed.), The General Assembly of Virginia, July 30, 1619-January 11, 1978 (General Assembly of Virginia, 1978), pp.125-127.

[27] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:23-27, 55 n.†, 10:160-161.

[28] Ibid., 10:375, 11:84.

[29] Gates, History of Public Land Law, pp.37-38.

[30] Neal Hammon and James Russell Harris, “‘In a dangerous situation’: Letters of Col. John Floyd, 1774-1783” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 83, no. 3 (1985), 213-214.

[31] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:52-54, 56, 58, 161. Richmond replaced Williamsburg as the state capital in 1780.

[32] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:50-52, 60-61

[33] Ibid., Statutes, 10:55-556 n.†, 159. One tract already in the possession of Richard Henderson was excepted.

[34] James A. Ramage, “The Green River Pioneers: Squatters, Soldiers, and Speculators,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 75, no. 3 (1977), 171-190, 172-173. The area was reduced by the 1779 Virginia-North Carolina (Kentucky-Tennessee) state line survey and expanded to the west in 1781 for an estimated net of six million acres.

[35] George W. Knepper, The Official Ohio Lands Book (Columbus: Ohio Auditor of State, 2002), 19.

[36] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:565; Robert A Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 3 vols. (University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 2:657.

[37] James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781, Virginia Series vol. 3 (Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), 413-415; William Shannon, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865 (Kentucky), Library of Virginia; Thomas Perkins Abernathy, Western Lands and the American Revolution (Russell & Russell, 1959), 301.

[38] James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 414-415, 417.

[39] Anon., ed., Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, session convening October 20, 1783 (Richmond: Thomas W. White, 1828), 71; James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 416.

[40] Hening, ed., Statutes, 11:335.

[41] Ibid., 11:83.

[42] Joseph Neville to Richard Clough Andersion, June 27, 1783, Anderson Latham Collection, folder 1, p.6, Library of Virginia, Richmond. I am not related to Joseph Neville.

[43] Abraham Hite, Jr. to Anderson, June 26 and July 28, 1783, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 1, pp.1-4, 6, 12-13, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[44] Elias Langham to Anderson, July 19, 1783, Anderson-Latham Collection, folder 1, p.10, Library of Virginia, Richmond; John H. Gwathmey, Historical Register of Virginians in the Revolution (1938; reprinted Genealogical Publishing, 2010), 373, 457.

[45] William Brent Bounty Land Claim, Library of Virginia.

[46] Hening, ed., Statutes, 11:309-310.

[47] William Pitt Palmer et al., eds., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (James E. Goode, 1875-1893), 3:550, 558

[48] Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, December 1821 session (Richmond: Thomas Richie, 1821 [sic.]), 220.

[49] Library of Virginia: Anderson-Latham Collection, 1771-1881, Acc. 23634, folder 5, p.1-4.

[50] Hening, ed., Statutes, 10:465-466.

[51] Palmer et al., eds., Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 4:475-477.

3 Comments

Excellent overview of the convoluted system for awarding bounty lands during and after the war. It truly was bewildering, and that’s before we consider the reactions of Native Americans already living on, or using, the land. It was a system that seemed designed to provoke conflict, not only between Native Americans and white settlers moving west, but also among the white settlers themselves. I seem to recall that some lawsuits between whites living in Kentucky under Virginia law and those who bought their lands through the Transylvania Company weren’t settled until after the Civl War. Discussions of land always bring the Delaware chief Gelelemend to my mind. He migrated from the east with his nation before the war as it consolidated itself in eastern Ohio. Over time, he should have had land claims recognized by multiple outside authorities, British, Native American, Virginian, and Pennsylvanian. He received a Captain’s commission in the Continental Army, and would have been entitled to land under that as well! I don’t think he got to enjoy any of those. Thank you for laying it all out so cleanly.

Thanks, Eric! There’s more to come on this. Three generations of my ancestors lived in the little town of Killbuck, Ohio. (For other readers: Killbuck was Gelelemend’s English name.) My grandfather was born there. I would love to know more about him.

Great article. My ancestor serviced in the Rev. War in Pennsylvania but then moved with other members of the Porterfield and Buster families to Kentucky after the war. Never could understand how or why they made this move there. A museum curator in Virginia said they were probably gifted bounty land in Kentucky from their uncle General Porterfield, who stayed behind in Staunton, VA. This article put more of the pieces together. My Kentucky Porterfield/Buster relatives eventually experienced tragedy with Indians or Tories in Kentucky so moved further west but their 2 lonely graves are still there in Kentucky where they homesteaded.