The American Declaration of Independence boldly proclaims “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” These words encouraged Americans to fight for freedom and have inspired disadvantaged groups though out the world. Historian Joseph Ellis called the phrase “the most potent and consequential words in American history, perhaps in modern history.”[1] This essay examines the origin, meaning and impact of these remarkable words.

John Adams, the Continental Congress’s leading proponent for independence, introduced a resolution on May 15, 1776 that each colony adopt their own government and constitution. Adam’s resolution stated that “authority under the said Crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted under the authority of the people . . . for the defense of their lives, liberties and properties.”[2] After its approval, Adams wrote that “Congress has passed the most important Resolution, that ever was taken in America.” It was a “compleat Separation from her [Britain], a total absolute Independence.”[3] Years later Adams believed the May 15 Resolution was the real declaration of independence and other documents were “Dress and ornament rather than Body, Soul and Substance.” He told Benjamin Rush that the Declaration of Independence was a “Theatrical Show [and] Jefferson ran away with . . . all the Glory of it”[4]

Although Continental Congress had been waging war for a year, delegates wanted unanimous support to formally declare independence. On April 12, 1776, North Carolina became the first legislature to authorize representatives to “concur with other delegates . . . in Declaring Independency.”[5] One month later, the Fifth Virginia Convention authorized their delegates to propose independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee proposed that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States.”[6] Congress postponed the vote for three weeks to assure unanimous approval. On June 11, Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of independence. Committee members included Thomas Jefferson (Virginia), John Adams (Massachusetts), Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania), Roger Sherman (Connecticut) and Robert Livingston (New York).[7]

The Committee of Five asked thirty-three-year-old Jefferson to write the first draft. Jefferson had established a reputation as a skillful writer in 1774 by enumerating grievances against King George III in A Summary View of the Rights of British America. He had recently written additional grievances which he sent to Williamsburg for inclusion in the Virginia Constitution. In fact, Jefferson was imploring the Virginia legislature to recall him from Philadelphia to Williamsburg to help write the Virginia Constitution, but Virginia recalled Richard Henry Lee instead.[8]

Jefferson remained in Philadelphia and rented the second floor of a three-story home at present day 700 Market Street where he wrote the first draft of the American Declaration of Independence. Jefferson was on three other committees and wrote two committee reports during the seventeen-days, from June11 to June 28, he had to write the Declaration. Jefferson probably did not miss Congressional sessions because two of six Virginia delegation members were absent. Furthermore, Congress usually met six days a week. Given these time constraints, Jefferson likely wrote the declaration over a few days. John Adams supposedly claimed that Jefferson wrote the declaration in a day or two.[9]

One month earlier in Virginia, George Mason wrote the Virginia Constitution and Declaration of Rights. Declaration of Rights proclaimed

That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural Rights . . . among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing and obtaining Happiness and Safety.[10]

Thomas Ludwell Lee, Richard Henry Lee’s brother, wrote some of the Virginia document which also included Jefferson’s charges against the King. The Virginia Convention first heard Mason’s draft on May 27 and ordered copies printed for review. On June 1, the Virginia Gazette published the draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. On June 12, one day after the Committee of Five was appointed, Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Gazette published the draft of the Virginia Declaration. Two other Philadelphia newspapers printed the document within two weeks. Jefferson and other committee members most likely saw a copy of the draft. Pauline Maier and other historians agree that Jefferson likely had “in hand two texts” when he drafted the Declaration of Independence: George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, and grievances against the King which Jefferson wrote for the Virginia Constitution.[11]

Although the draft of the Virginia Declaration had been widely published, the Virginia Convention made changes and did not approve it until June 12. Most delegates were enslavers and had difficulty with “all men are born equally free.” One delegate, Robert Nicholas, predicted the statement could be “the forerunner of . . . civil convulsion.” Edmund Pendleton proposed qualifying the phrase with “when they enter a state of society.” Enslaved people were not “constituent members of society” and therefore would not have the proposed rights. The Virginia Convention approved the Declaration of Rights with changes shown in parenthesis

That all men are (by nature) equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, (when they enter into a state of society,) . . . the enjoyment of . . .[12]

Despite these changes, newspapers throughout the colonies continued publishing Mason’s first draft, rather than the approved version.

Jefferson began the Declaration of Independence by stating “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” His first draft continued,

that all men are created equal and independent; that from that equal Creation they derive Rights inherent and unalienable; among which are the preservation of Life, and Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.[13]

Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights draft stated,

That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural Rights . . . among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing and obtaining Happiness and Safety.[14]

Both documents stated that governmental power is derived from the people and if government is inadequate or destructive, people should “alter or abolish it.” These remarkable similarities suggest that Jefferson referred to the Virginia Declaration when writing the American Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson listed twenty-one abuses against the king including imposing standing armies “in times of peace,” taxing without consent and suspending colonial legislatures. He stated that the king had “destroyed the lives of our people . . . [and was] transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation & tyranny.” John Adams and Benjamin Franklin made a few changes to his initial draft.[15]

On Friday June 28, the Declaration “was read” to Congress and the draft ordered “To lie on the table.” Congress reconvened on Monday July 1, as 130 British war ships arrived in New York Harbor and 53 ships appeared near the coast of Charlestown, South Carolina.[16] Congress voted on Lee’s resolution for independence and only nine colonies voted affirmatively. South Carolina and Pennsylvania were opposed; two Delaware delegates disagreed and New York’s Provincial Congress had not authorized delegates to vote.

Congress met again on July 2 while British troops disembarked on Staten Island. South Carolina’s delegates voted affirmatively. John Dickinson and Robert Morris from Pennsylvania opposed independence and did not attend the session. James Wilson changed his vote and joined Benjamin Franklin and John Morton in voting for independence. Caesar Rodney broke Delaware’s tie by riding seventy miles during a midnight thunderstorm and voting for independence. Twelve colonies voted for independence; New York continued to abstain.[17] After the affirmative July 2 vote, and for most of July 3 and 4, Congress formed a “committee of the whole” and carefully edited Jefferson’s draft. Delegates improved the wording of many sentences and eliminated twenty-five percent of the document.[18] They removed a section blaming the king for importing slavery which Jefferson called “a cruel war against human nature itself.” Congress also eliminated sentences disavowing a bond with “British brethren,” claiming the injustices were “the last stab to agonizing affection; and manly spirit bids us to renounce forever these unfeeling brethren.” Delegates retained Jefferson’s pledge to hold the British people “as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.”

In the final paragraph, Congress added an appeal “to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions” and inserted “a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence.” Delegates eliminated Jefferson’s statement to “renounce all allegiance and subjection to the kings of Great Britain, & all others who may hereafter claim by, through, or under them.” They inserted Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence, “That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown.” Congress retained Jefferson’s last sentence, “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”[19]

Jefferson resented these changes and admitted “writhing a little under the acrimonious criticism.”[20] He later made Declaration copies which he sent to a few friends with deleted sections restored and Congress’s changes placed in the margins. Richard Henry Lee thanked him, stating that “the Manuscript had not been mangled . . . pitiful, that the rage of change should be so unhappily applied.” Edmund Pendleton, president of the Virginia Convention, also responded with consolation and reassurance.[21]

On July 4, 1776, “After some time,” delegates approved the Declaration which was again read aloud and called “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.” [22] The Declaration probably was not signed on July 4, although records are conflicting. Twenty-nine-year-old John Dunlap, a nearby printer, worked throughout the night of July 4 and made perhaps 200 copies printed on one side of a single sheet of paper, now known as Dunlap broadsides. Since New York delegates had not approved the Declaration, “unanimous” was removed from the title, and the names of John Handcock and Charles Thompson, president and secretary of Congress respectively, were printed as signing and attesting to the Declaration.

Congress ordered the Declaration sent to various groups. It was soon reprinted in newspapers and read aloud throughout the colonies often igniting celebrations. One copy was sent to England and on July 9 the Continental Army in New York, facing British warships in the harbor, gathered to hear the Declaration.[23]

On July 9, the New York legislature gave their delegates permission to vote for independence and on July 19, a majority of New York delegates approved the Declaration. The Continental Congress then ordered “That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and style of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America.’” Timothy Matlack, clerk to the secretary of Congress, created a handwritten parchment copy of the Declaration. On August 2, “The declaration of independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed.”[24]

In 1811, Benjamin Rush recalled the mood of August 2, “a pensive and awful silence which pervaded the house when we were called up, one after another to the table . . . to subscribe what was believed by many . . . to be our own death warrant.” Rush continues “The Silence & gloom of the morning were interrupted . . . only for a minute by [rotund] Col: Harrison of Virginia who said to [slender] Mr Gerry at the table, ‘I shall have a great advantage over you . . . when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead.’ This Speech procured a transient smile.”[25] On August 2, forty-nine delegates signed the Declaration and most not present on that day signed over the next four months.[26] In all, fifty-six patriots from thirteen states courageously signed “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.”

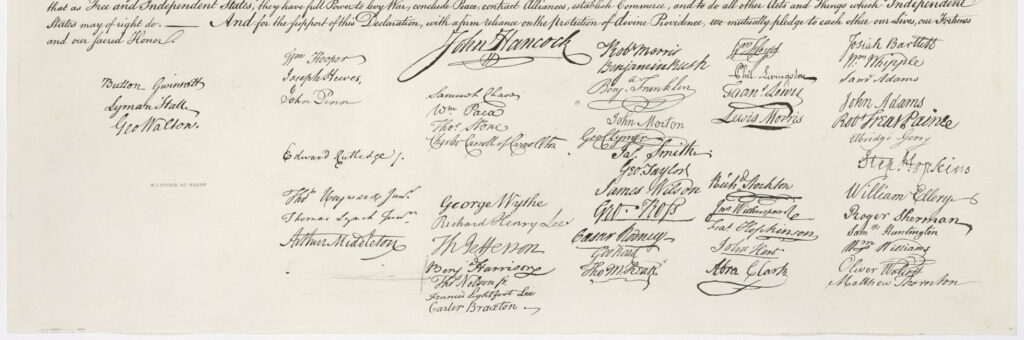

In 1774 and 1775, Continental Congress delegates signed Articles of Association, a Petition to the King, and an “Olive Branch” Petition. New Hampshire delegates signed the documents first underneath the text on the upper left. Other delegates from Northern to Southern colonies signed in columns progressing from left to right. However, in signing the Declaration of Independence, New Hampshire delegate Josiah Bartlett curiously signed on the upper right and delegates from Northern to Southern states signed in columns progressing from right to left. (Figure 1) This unusual progression for English and other modern languages created an asymmetrical distribution of signatures with open spaces on the left and only three Georgia signatures in the far-left column. Northern signatures on the right are crowded and overlapping. The Declaration displays an unusual distribution of remarkable signatures of John Hancock, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, James Wilson, Robert Morris and Roger Sherman. Delegates signed two other documents in 1778 and 1789, Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. Oddly, these documents were also signed from right to left.

Jefferson and Continental Congress delegates created a masterful document justifying separation from Great Britain and declaring the rights of man and the role of government. Many of these concepts originated from British Enlightenment writers who educated colonists knew well. John Locke wrote in 1689 that men are “by nature, all free, equal, and independent” and the rights of men include “his property, that is, his life, liberty and estate.”[27] John Adams wrote that “the lowest of the people are . . . entitled to . . . light to see, food to eat . . . All men are born equal.”[28] George Mason envisioned rights of man as life, liberty, property, happiness and safety. Jefferson included life, liberty and happiness and curiously excluded property. In 1764, James Otis wrote that government should provide “Happy enjoyment of life, liberty and property.”[29] James Wilson believed that “happiness of the society is the first law of every government.” John Adams agreed “happiness of society is the end [that is, the goal] of government.”[30]

After the Declaration of Independence was approved and publicized, it was largely forgotten. George Washington became president in 1789 and was followed by John Adams. Both promoted a strong federal government. Jefferson defeated Adams after one term and became president in 1801, advocating decentralized government, strong states’ rights and individual rights of man. The Declaration of Independence regained recognition during Jefferson’s presidency and as anti-British sentiments increased during the War of 1812.

In 1819, the North Carolina Raleigh Register published a Declaration of Independence supposedly written in May 1775 in the rural county of Mecklenburg, North Carolina but never publicized. With no definitive evidence of its existence before 1819, the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration remains controversial to this day.[31] Nonetheless, when John Adams read a Massachusetts newspaper article about it, he sent a copy and an inquiry to Jefferson. Jefferson noted similar phrases in both Declarations and compared the Mecklenburg Declaration to a “volcano . . . having broken out in North Carolina . . . I believe it spurious.”[32] Adams wrote that Jefferson had “copied . . . the expressions of it verbatim into his Declaration.” He later concluded that “Either these resolutions are a plagiarism from Mr. Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, or Mr. Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence is a plagiarism from those resolutions.”[33]

Later in his life, Jefferson responded to other accusations of plagiarism. In 1823, he wrote that Richard Henry Lee claimed the Declaration was “copied from Locke’s treatise” and that John Adams said it was “contained in Otis’ pamphlet.”[34] Jefferson explained that in writing the Declaration he was “harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversations, in letters, printed essays or in the elementary books of public right.” He was “neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing.”[35] “Whether I had gathered my ideas from reading or reflection I do not know. I know only that I turned to neither book nor pamphlet while writing it.”[36] Most likely Jefferson turned to Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and he may have referred to a copy of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

In 1819, Congress debated whether Missouri, a slave state, should be admitted to the union. For Jefferson, allowing government to control slavery represented a failure of individual rights of man and American Revolutionary ideals. Jefferson wrote that legislating slavery, “a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror . . . the [death] knell of the Union.” He admitted “I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves, by the generation of ’76 . . . is to be thrown away . . . my only consolation is to be that I live not to weep over it.[37]

Jefferson supported individual rights and proposed that “each generation [has] a right to choose for itself the form of government . . . most promotive of its own happiness.” Jefferson’s generation did not resolve the evils of slavery. He proposed gradual emancipation and deportation but admitted that “justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” In his Autobiography he wrote “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [slaves] are to be free.” [38]

Three months before his death, Jefferson requested that his tombstone state he was “Author of the Declaration of Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia.”[39] Although he was probably more draftsman than author, he found solace in his contribution to the Declaration of Independence. Within six months of his death, Jefferson’s heirs in order to pay debts sold Monticello and auctioned one hundred and thirty slaves, men, women and children. In his will, Jefferson freed five of Sally Heming’s male children; two were his sons.[40] A eulogist in Maine claimed that the Declaration was a testament to “the native equality of the human race . . . this great truth was proclaimed to the world.”[41]

As Western territories continued to joined the Union, debates over slavery and the true meaning of the Declaration intensified. South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, debating Oregon’s admission, claimed in 1848 that “all men are created equal” is a “hypothetical truism,” which has “fixed itself deeply in the public mind” and was inserted in the Declaration “without any necessity.” Calhoun predicted that the controversy would “ingulf . . . our political institutions, and involve the country in countless woes.”[42] In 1854, Congressman John Pettit, referring to “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” stated “I hold it to be a self-evident lie . . . tell me that the imbecile . . . is my equal physically, mentally . . . and you tell me a lie.”[43]

Abraham Lincoln opposed expansion of the “monstrous injustice of slavery” and ran for the Senate against Stephen Douglas in 1858. During their debates, Douglas noted that many Declaration signers were slave holders and claimed that if “every man who signed the Declaration of Independence declared the negro his equal . . . you charge the signers of it with hypocrisy.”[44] Douglas won the election.

The Declaration’s proclamation remained controversial, to the point that controversy ignited civil war. The document nonetheless declares a fundamental principle upon, one upon which American independence was based: “All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

[1] Joseph J. Ellis, American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic (New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 2007), 56.

[2] “Friday, May 10, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 4:342; “Wednesday, May 15, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 4:358.

[3] John Adams to James Warren, May 15, 1776, Papers of John Adams, ed. Robert J. Taylor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 4:186-187; John Adams to Abigail Adams, May 17, 1776,” in The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 1:410-412.

[4] John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1813, in The Adams-Jefferson Letters, ed. Lester J. Cappon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,1959), 2:392-393; John Adams to Benjamin Rush, June 21, 1811,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5649.

[5] “Minutes of the Provincial Congress, April 12, 1776,” Colonial Records of North Carolina, ed. William Saunders (Raleigh: Josephus Daniels, 1890), 10:512.

[6] “Friday, June 7, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:425.

[7] “Tuesday, June 11, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:431.

[8] John Ferling, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson and the American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 131-132.

[9] Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 102-104.

[10] George Mason, “First Draft of The Virginia Declaration of Rights,” in The Papers of George Mason, ed. Robert A. Rutland (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 1:276-278.

[11] Maier, American Scripture, 125-129, 268; Nobel E. Cunningham, In Pursuit of Reason: The Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Ballantine, 1987), 47-50.

[12] Mason, “Final Draft Declaration,” The Papers of George Mason, 1:287-291.

[13] Thomas Jefferson, “First Draft, A Declaration by the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in General Congress assembled,” in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford, (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 2:133-140; “Friday, June 29, 1776” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:492.

[14] Mason, “First Draft Declaration,” 1:276-278.

[15] “Friday, June 28, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:491-502; Jefferson, “Reported Draft, A Declaration,” The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 2:141-144.

[16] John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 124; Maier, American Scripture, 44-46.

[17] David McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 134-135; Francis D. Cogliano, Revolutionary America, 1763-1815: A Political History (London: Routledge, 2000), 67-68.

[18] “Tuesday, July 2, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:506-507.

[19] “Thursday, July 4, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:510-515; Jefferson, “Reported Draft,” The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 2:141-144; Jefferson, “Engrossed Copy,” The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 2:145-147.

[20] Jefferson to James Madison, August 30, 1823, The Works of Thomas Jefferson,12:308.

[21] Richard Henry Lee to Jefferson, July 21, 1776, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 1760-1776, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 1: 47; E. Pendleton to Jefferson July 22, 1776, August 10, 1776, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 1:245.

[22] “Thursday, July 4, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:509-515.

[23] Maier, American Scripture, 155-160; McCullough, 1776, 137.

[24] Maier, American Scripture, 150-151; “Friday, July 19, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:590-591; “Friday, August 2, 1776,” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:626.

[25] Rush to John Adams, July 20, 1811,” Founders on Line, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5659.

[26] Robert Ferris, Richard Morris, Signers of The Declaration of Independence (Arlington, Virginia: Interpretive Publications, 1982), 100, 140.

[27] John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (Project Gutenberg E Book, 2010), vol. 4, Ch. 8, sect. 95, p. 32, Ch. 7, sect. 87, p. 28.

[28] John Adams, “The Earl of Clarendon to William Pym. No. III,” in The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1865), 3:356.

[29] Patrick J. Charles, “Restoring ‘Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness’ in Our Constitutional Jurisprudence,” William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 20, no. 2 (2011-2012): 457; James Otis, “Rights of the British Colonies,” in Collected Political Writings of James Otis, ed. Richard Samuelson (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2015), 125.

[30] James Wilson, “Considerations, August 17, 1774” in Collected Works of James Wilson, ed. Kermit L. Hall, Mark David Hall (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007) 1:20; Adams, “Thoughts,” Works, 4:131.

[31] Scott Syfert, The First American Declaration of Independence? The Disputed History of the Mecklenburg Declaration of May 20, 1775 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014), 68-149; V. V. McNitt, Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence (Palmer, Massachusetts & New York: Hampden Hills Press, 1960), 32-82.

[32] John Adams to Jefferson, June 22, 1819,” The Works of John Adams, 10:355; Jefferson to John Adams, July 9, 1819, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:131-134.

[33] John Adams to William Bentley, July 15, 1819, The Works of John Adams, 10:381; John Adams to Bentley, August, 21, 1819,” The Works of John Adams, 10:383.

[34] Jefferson to Madison, August 30, 1823, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:306-309.

[35] “Thomas Jefferson to Richard Henry Lee, Monticello, May 8, 1825,” The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:408-409.

[36] Jefferson to Madison, August 30, 1823, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:306-309.

[37] Jefferson to John Holmes, April 22, 1820, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, ed. J. Jefferson Looney (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 550–551.

[38] Jefferson to Samuel Kercheval, July 12, 1816, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:13; Jefferson to Holmes, April 22, 1820, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, 550-551; Jefferson Autobiography, January 6, 1821, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 1:48-49.

[39] Jefferson’s Will, March 1826, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, 12:483.

[40] “After Monticello,” Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello, Smithsonian NMAAHC/Monticello, web.archive.org/web/20120411071606/http://www.slaveryatmonticello.org/slavery-at-monticello/after-monticello.

[41] “Eulogy Pronounced at Boston, Massachusetts, August 2, 1826, by Daniel Webster,” “Eulogy Pronounced at Hallowell, Maine, July 1826, by Peleg Sprague,” in A Selection of Eulogies, Pronounced in the Several States, in Honor of Those Illustrious Patriots and Statesmen, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (Hartford: D. H. Robinson & Co. and Norton & Russell, 1826), 195, 145.

[42] John C. Calhoun, “Speech on the Oregon Bill, June 27, 1848,” Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun, ed. Ross M. Lence (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund,1992), 354-356.

[43] John Pettit, February 20, 1854, 33d Congress, First Session, Appendix to the Congressional Globe, 214, www.congress.gov/congressional-globe/appendix-page-headings/33rd-congress/1st-session/14828.

[44] Abraham Lincoln, “First Debate at Ottawa, Illinois,” 7; Stephen A. Douglas, “Fifth Debate at Ottawa, Illinois, October 7, 1858,” 5, archive.org/details/LincolnDouglasDebateTranscripts/Transcript%20Lincoln%20-%20Douglas%20Debate%205/.

3 Comments

Thoroughly researched and a succinct presentation, especially given the article’s breadth.

A very interesting article, thank you! A more general question, if you please? It is my impression that the English Bill of Rights rarely gets a look-in on this topic, while Locke in the same year always gets a nod or two. There are commonalities in the format of the two declarations including the complaints against the king and his government, and broad appeals to rights (“Subject’s… Vindicating and Asserting their auntient Rights and Liberties” in 1689 rather than being “endowed by their Creator” in 1776). The question to answer was posed in 1649 by Charles I at his trial: “By what authority, I mean lawful, am I called hither?” Parliament in 1689 and Congress in 1776 provided lasting written replies that are worth referencing.

This article is a gem. Sparkling. Excellent research. Wide and deep. Thank you so very much. I have come through personal study to similar conclusions. Indeed, the Declaration of Independence drew from a number of tributaries. Lee, Mason, Jefferson, Adams and others were gifted thinkers and writers with a passion for freedom, fair play, liberty with responsibility. They understood the extremes of anarchy and authoritarianism. These men in turn drew from Locke and those before. Moreover, as a theologian, I see that all the salient wondrous things in the Declaration find an address in the Sacred Scriptures. Michael Novak with his insightful work articulates some of the Hebrew roots of American founding. Your articles adroitly draw from primary sources. With the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence on the horizon is most important to grasp the opponents and components of liberty lest we repeat the melancholy moments of the past.