On March 7, 1778, one of the deadliest naval battles of the Revolutionary War occurred off the coast of Barbados between the British ship Yarmouth and an American squadron led by the Continental frigate Randolph. The five-ship American contingent which sailed from Charlestown, South Carolina, led by Capt. Nicholas Biddle, was the largest joint Continental and state navy operation from that place during the war. Despite the relatively large assemblage of ships, the battle was brief and ended with the explosion of the Randolph and the deadliest seconds of the war.

The naval squadron which left Charlestown in February 1778 was a diverse mixture of ships and men. Of the four South Carolina vessels only one, the Notre Dame (eighteen 4-pound guns), was formally part of the state navy. Three ships, the Fair American (fourteen 4- and sixteen 6-pounders), General Moultrie (eighteen 4- and 12-pounders), and Polly (fourteen 4- pounders), had been privateer vessels until late 1777 when they were taken into state service. As diverse as the ships were the men who manned them, consisting of seasoned naval officers and crewmen, former prisoners, and men who had never been to sea before.

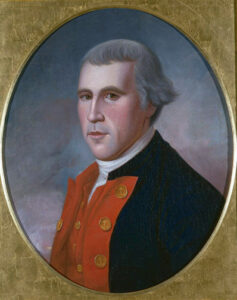

Certainly, the most well-known American captain and ship at the battle was twenty-seven-year-old Capt. Nicholas Biddle of the newly built Continental frigate Randolph. Biddle came from an established Philadelphia family and first went to sea at fifteen years old.[1] After a short time on a merchant ship, he went to London to seek a commission in the Royal Navy. He was soon rated a midshipman and served for a time on the man-of-war Portland. In 1773, he went on board the Carcass on a voyage of discovery to the Arctic Circle accompanied by a fellow midshipman named Horatio Nelson.[2] With the likelihood of open conflict in the American colonies, Biddle resigned his commission and returned to Philadelphia where, in August 1775, he held a commission in command of the state galley Franklin. By January 1776, Biddle received a commission from Congress and command of the Continental Navy brig Andrew Doria (fourteen guns, 130 men). In March, he was part of an expedition to the Bahamas where Continental Marines marched into Nassau and briefly took control of the town.[3] By mid-1776, not yet twenty-six years old, Biddle was already considered one of the most able captains in the navy, having also been successful in the capture of several commercial vessels.

On June 12, 1776, Biddle was named captain of the thirty-six gun frigate Randolph, one of the first warships authorized by the Continental Congress.[4] Built in Philadelphia that year by Joshua Humphreys and John Wharton, the ship measured 137 feet in length, 34½ feet in breadth, and about 690 tons.[5] There were twenty-six 12-pounders on the main gun deck and ten 6-pounders mounted on the forecastle and quarterdeck.[6]

Finding a crew for the Randolph proved to be difficult. In December, Congress empowered Biddle “to enlist in the Continental Service such of the sailors in the prison as he shall think proper.”[7] A British correspondent later speculated that nearly half the crew on the Randolph were former British sailors who enlisted to get out of prison.[8] On February 6, 1777, the Randolph set sail.[9] Captain Biddle declared the ship “the very best vessel for sailing that I ever knew.”[10]

The Randolph soon joined the multitude of ships in Charlestown. On arrival in the town, Captain Biddle befriended Richard Bohun Baker, a captain in the South Carolina Continental Line. On a visit to Baker’s family plantation, Biddle met his sister Elizabeth Elliott Baker. According to Biddle’s principal biographer, he soon became engaged to her. Biddle also acquired land, being listed in legal documents as acquiring 730 acres on the Wateree River from Joseph and Sarah Kershaw.[11] In early 1778, Biddle made a will leaving most of his property ($25,000 of South Carolina currency) to Elizabeth with the remainder to his mother and siblings.[12]

By late 1777, the Royal Navy was sending more ships to cruise the Carolina and Georgia coasts. Three Royal Navy warships, the Carrysfort (or Carysfort), Perseus, and Hinchinbrook appeared on the coast and effectively blockaded the Charlestown port. According to a few accounts, men from these vessels sometimes came ashore to converse with Loyalists.[13] Some sources speculated that these sailors and/or Loyalists ignited a fire in the city on January 15, 1778.[14]

Given the number of trading vessels captured off the bar and held in port, there was enormous pressure on navy commissioners and the state political leadership to clear the coast of enemy ships. In late 1777, only two warships were known to be in the Charlestown port, the Notre Dame and Randolph. On December 12, with the British ships still offshore, South Carolina’s president ordered four privateer ships to be taken into South Carolina service: the Fair American, General Moultrie, Polly, and Volunteer.[15] With stipulations that the crews only be held to one cruise and a bounty of thirty dollars, over 300 men signed up to crew the four vessels. Even with an influx of new sailors there were still not enough men for four ships. As such, the Volunteer, judged the least capable vessel, was removed from the coming expedition to break the blockade.

The new state navy ships and captains which were to accompany the Randolph on clearing the Charlestown bar are somewhat difficult to trace. Commanding three of the ships were experienced privateer captains.[16] Hezekiah Anthony, captain of the Polly, had been a lieutenant in the state navy in 1776 but left the service for a privateer ship in early 1777. Anthony was in several engagements with armed vessels before taking command of the Polly later that year. Charles Morgan of the Fair American was also an experienced privateer captain, being in service about the same time. He, with a captain named Francis Morgan, possibly his brother, briefly captured a fort on the west end of Bermuda in 1777. Morgan later captured several prizes on the return cruise. Less is known about Capt. Phillip Sullivan of the General Moultrie, but he was also listed as a captain of several privateer vessels in 1776 and 1777.[17]

Little is known about the four South Carolina vessels. According to one source the Notre Dame was a converted schooner named Islington and was involved in over half the merchant captures made by the South Carolina Navy in the war.[18] The first extant source on the Fair American pertains to its June 1777 action in Bermuda.[19] Even less is known of the General Moultrie and Polly privateers prior to 1778; both were thought to have been merchant vessels converted to privateer brigs. The Polly is first listed in Charlestown as a schooner in December 1776.[20] The General Moultrie is listed as a privateer in 1777, initially under the command of Jacob Johnston.[21]

By early January 1778, the three South Carolina privateers were under contract for six months service and ordered to join the Randolph near the mouth of the harbor. That same day, Capt. Joseph Ioor of the 1st South Carolina Regiment with fifty-two men boarded the Randolph with about one hundred other Continentals sent on board the other ships as marines.[22] One South Carolina Continental soldier reported a degree of coercion to go into the sea service. In early 1778, just as his enlistment was about to expire, he recalled that he was placed in the “prevost guard house” with several others in order to compel them to re-enlist. The next day a recruiting party arrived with bounty money, and he re-enlisted for service on the Fair American.[23]

On February 14 the wind turned and the squadron finally set sail. By some accounts, eighteen merchant ships also cleared the Charlestown bar that day. Perhaps as a surprise to all, no British ships were encountered off the coast. They had either removed to St. Augustine for replenishment, to escort in their prisoners, or in one instance went in pursuit of an inbound vessel.[24] The five-vessel squadron which put to sea contained as many as 770 men. About 315 of these were on board the Randolph, about 156 seamen on board the General Moultrie and approximately 100 more on board each of the three brigs.[25]

Escorting the few trading vessels for a time, the squadron soon arrived in the Caribbean to intercept British shipping. For three weeks the voyage was uneventful as they approached Trinidad and Tobago. On March 4 the Polly captured a small merchant ship which was made into a tender for the squadron.[26] Events changed at 5 p.m. on Saturday, March 7, sixty leagues to the east of Barbados when a large ship appeared to the northeast of the squadron. The ship turned out to be the Yarmouth, a two-decked, sixty-four-gun, third rate Royal Navy ship of the line commanded by Capt. Nicholas Vincent.[27] Upon spotting the six American vessels to the southwest, the Yarmouth immediately bore down on the American squadron.

Only seeing a large ship approach, those in Biddle’s squadron were unsure if it was a warship. According to participant accounts, there appeared to be no plan for how the ships were to proceed if this ship was an enemy vessel. One participant indicated that as soon as Captain Biddle saw it was a ship of the line he “hove out a signal to make sail.”[28] The captain of the Notre Dame afterward stated that Biddle “hove out no signal for drawing up in a line of battle, but laid his mizzentopsail to the mast, and got ready to engage.”[29] Charles Biddle postulated that since the General Moultrie did not heed the sailing order, the Randolph was obliged to engage the Yarmouth or lose the General Moultrie. Whether Biddle intended for the entire squadron or just the Randolph to engage the Yarmouth may never be known. Regardless, by the time the squadron could determine the ship was an enemy, three ships of the squadron were now within range of the Yarmouth’s guns.

Between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m., with its colors flying, the Yarmouth came within hailing distance of the closest ship, the General Moultrie. With their ensigns lowered, the General Moultrie answered the hail by claiming to be the Polly out of Charlestown. Next in line, the Randolph answered in an entirely different manner, raising its ensign and immediately firing a broadside from its thirteen 12-pounders. By several accounts, the Randolph began the battle with a flurry of cannon fire, firing at several times the rate of the Yarmouth. Captain Vincent later reported the Randolph “kept up his firing very smart for a quarter of an hour.”[30]

The unfolding battle became one almost entirely between the Randolph and Yarmouth. Within 100 yards of the Yarmouth at various points were the General Moultrie and Notre Dame. The Notre Dame fired a broadside early in the engagement which almost hit the Randolph.[31] According to Captain Blake of the 2nd South Carolina Continental Regiment on the General Moultrie, that ship fired three broadsides, with at least a few shots hitting the Randolph.[32] The two ships remained close by but could not fire out of fear of hitting the Randolph. Essentially alone in the fight, the Randolph was badly outgunned, the Yarmouth having twice the number and also higher caliber guns—eighteen 18-pounders to the Randolph’s 12-pounders. The Yarmouth also had substantially more men aboard, 483 including 87 marines.[33]

By all accounts the Randolph held its own in the fight, firing three or four times as fast as the Yarmouth, damaging their sails and rigging but also shooting away their bowsprit and part of the foremast. Five British sailors were killed and twelve wounded.[34] American casualties from the battle cannot be determined, but Captain Biddle was wounded in the leg and directed the battle from a chair on the main deck. Participants provided no more details of the battle itself, but there was no doubt what happened next. After about fifteen minutes of exchanging fire at a distance of three to four ship lengths or closer, the Randolph inexplicably exploded. Clear to everyone that could see, the powder magazine had ignited. Whether it was from an internal source or fire from the Yarmouth will likely never be known.

The explosion commenced what are thought to have been the deadliest seconds of the war with as many as 301 men losing their lives instantly or in the next moments. Some qualification is necessary to this claim. From the available accounts, the vast majority of the 301 men on the Yarmouth were assumed to have died instantly in the massive explosion or some seconds later in the water from their injuries, impact with the water, or drowning. Only one eyewitness mentioned survivors. Captain William Hall of the Notre Dame noted that the Yarmouth in the aftermath of the explosion “never stopped to save one man, but let them all drown.”[35]

Hall’s statement raises the critical question: did he see them or just assume there were survivors? By this time it was mostly dark, if not completely so. As he could not have seen possible survivors it would seem unlikely that he could have heard them. The most definitive record is from the four American survivors. Three men who survived in the water for five days after the battle later gave a sworn statement that made no mention of other survivors. One of the survivors later spoke with Charles Biddle and said nothing about other survivors.[36]

The naval battle off Barbados was the eighth most deadly battle of the war in terms of American losses.[37] There were more deaths from the Randolph than the better-known Battle of Flamborough Head which had 302 killed and wounded. Three well-known naval battles between the British and French at Ushant (1778), the Capes (1781), and the Saintes (1782) were far more deadly, having upwards of several times more deaths and casualties, broadly speaking. Numerous vessels, both larger and smaller than the Randolph, were lost at sea during the war as well. It would be impossible to determine how and over what period of time men from these ships perished and more importantly how many lives were on board. The most deadly known naval accident of the war occurred with a ship in port. The largest ship in the world, the 100-gun Royal George, sank while being repaired in 1782 near Portsmouth with the loss of between 800 and 1,000 men, women, and children.[38] There was at least one large gunpowder explosion with a large loss of life during the war. Some estimates of the magazine explosion in Charlestown on May 15, 1780, were that upwards of 300 people perished; it is more likely that nearly 100 people died in the explosion with perhaps the same number of injured.[39] It is likely that the explosion of the Randolph was the most deadly violent moment of the war, almost instantly taking the lives of 200 to 300 men.

Little has been written about the aftermath of the battle. Seconds after the explosion, parts of the Randolph rained down on the Notre Dame and Yarmouth, including an intact American ensign on board the latter. On the General Moultrie, Captain Sullivan had the colors lowered in surrender, but Captain Blake of the South Carolina Line intervened and informed the crew to make sail and depart the area. The Yarmouth attempted to pursue the American ship but due to the darkness and damage to their sails and rigging they soon gave up the chase.

Five days later the Yarmouth was patrolling in the area of the battle when it spotted a raft with a sail. Remarkably, the four men brought on board the Yarmouth, Hantz Workman (Wortman), John Kerry (Carew), Alexander Robinson, and Bartholomew Boudreau (Bordeaux), were survivors of the Randolph explosion. By their accounts they were members of the same gun crew in the captain’s quarters at the stern of the ship when the explosion occurred. Blown clear of the ship, they landed in the water relatively unscathed. All being good swimmers, they were able to fashion a raft from the wreckage. With no food they survived by drinking rainwater from a blanket. On board the Yarmouth, the rescued men reported they were not hungry but overwhelmingly tired. They were offered hammocks and hot tea. The men’s names were entered into the ship’s muster book as supernumerary prisoners. In Barbados they testified on what happened to the ship; their testimony being an important part of the “head bounty” paid for American sailors killed by the British Navy.[40]

The men remained on the musters of the Yarmouth through May when the ship went back to sea for Antigua. According to one muster, the four men were discharged in April 1778 with one, Bartholomew Bourdeau, being listed as sick at the hospital on the island.[41] Later musters noted three of the Randolph men serving on the Yarmouth. John Kerry was an able seaman until May 1780 when he deserted on the island of St. Lucia. Alexander Robinson rose to the rank of quarter-gunner in November 1778 and remained in the Royal Navy until February 1781 when he was discharged at Stonehouse Hospital in Plymouth, England. Nothing more is presently known about Hantz Workman beyond a note that his wages were “paid to [a] trustee” sometime in 1781.[42]

On the return to Charlestown from the battle, the Notre Dame captured eleven prizes, half of which made it to a safe port.[43] Captain Hall later resigned his commission, seemingly as a result of having been accused of failing to support Captain Pyne when his galley was under attack by a British ship. The General Moultrie and Notre Dame were in Charlestown harbor when the British fleet arrived in 1780 and were scuttled before the surrender of the city.[44] William Hall was made prisoner but soon paroled. In late 1780, he was one of sixty-three Charlestown men arrested and sent to St. Augustine, East Florida.

The Fair American and Polly returned to their owners after fulfilling six months service.[45] Not much is known about the two privateers in the late war period. By at least one account, Captain Anthony of the Polly was also captured at Charlestown but soon broke his parole and went to Philadelphia where he captained another privateer vessel, and was at sea as late as July 1781.[46]

The legacy of the battle off Barbados is somewhat complex. There was a degree of consternation among South Carolina leaders over the endangerment of the balance of their fleet on the cruise. The criticism spoke to a difference of doctrine between the Continental Navy, state navies, and privateers. In a broad context, the South Carolina Navy existed to defend the coast, prey on enemy merchant ships and supplement the Continental Navy. The port of Charlestown remained largely open, wartime trade flourished, and many merchants and warships were captured up until the city was captured in 1780. At a minimum, its ships and sailors, whether in the navy, privateer service, or in many cases both, faced enormous challenges with limited resources and fared moderately well for most of the war.

The explosion of the Randolph was a massive blow to the Continental Navy in men and material. It deprived the Continental Navy of one of its new frigates and most experienced captains, officers, and crew. For Captain Biddle, the crew, and the vessel the unanswerable question remains in what the men would or could have achieved had they survived the battle with the Yarmouth.

If a conclusion had to be drawn from battle, it may be best to judge the squadron not by what they achieved but by what they sought to overcome. The captains and crews of these three naval entities were never going to thwart, much less defeat, the Royal Navy. That they faced their enemy amid an uncertain outcome is a testament to their bravery and valor. Captain Biddle and his heroic fleet of sailors and ships may not have known it but they were a small but important nucleus of an expansive, storied naval heritage and historical tradition that is entering its second quarter of a millennium.

[1] Edward Biddle, “Captain Nicholas Biddle (Continental Navy),” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 43 No. 9 (September 1917), 175.

[2] Tim McGrath, “I Fear Nothing,” Naval History Vol. 29 No. 4 (August 2015).

[3] William Bell Clark, et al. ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (United States Government Printing Office, 1964 -), 4:373 (NDAR).

[4] NDAR, 5:479

[5] William Bell Clark, Captain Dauntless: The Story of Nicholas Biddle of the Continental Navy (Louisiana State University Press, 1949), 155.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Journals of the Continental Congress, December 7, 1776, VI:1009.

[8] NDAR, 12:231.

[9] Clark, Captain Dauntless, 174

[10] NDAR, 8:89.

[11] “Kershaw, Joseph And Wife To Nicholas Biddle, Lease And Release For 730 Acres On The West Side Of Wateree River And 150 Acres On The East Side Of Wateree River,” February 4, 1778, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Conveyance Books (Register of Mesne Conveyance) (S363001), 05C0 Page: 00021.

[12] Will of Nicholas Biddle, Charles Town, SC, January 12, 1778, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, South Carolina Wills (WPA Transcripts) 1774-1784 (S146002)

[13] Tim McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America’s Revolution at Sea (Penguin, 2015), 208.

[14] Harold A. Mouzon, Privateers of Charleston in the Revolution, (Unpublished Manuscript, ca. 1950), South Carolina Historical Society, 17.

[15] Michael J. Crawford (ed.), NDAR, 10:716.

[16] Heyward A. Stuckey, “ The South Carolina Navy and the American Revolution,” (Master’s Degree Thesis, University of South Carolina, 1972), 72.

[17] Mouzon, Privateers of Charleston, 4-6, 14-15, 49.

[18] John J. Sayen, Jr., “Oared Fighting Ships of the South Carolina Navy, 1776-1780,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 87 No. 4 (Oct., 1986), 225.

[19] NDAR, 8:194.

[20] Mouzon, South Carolina Privateers, 48.

[21] Mouzon, South Carolina Privateers, 50.

[22] Clark, Captain Dauntless, 230-1.

[23] Pension Application of William Taylor (R10439), National Archives and Records Administration.

[24] Clark, Captain Dauntless, 235.

[25] John Wells Jr. to Henry Laurens, February 17, 1778, Henry Laurens Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina. Accessions 13612.

[26] Clark, Captain Dauntless, 237.

[27] Journal of the HMS Yarmouth, NDAR, 11:543-44.

[28] Charles Biddle, Autobiography of Charles Biddle, Vice President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, 1745-1821 (E. Claxton and Company, 1883), 107.

[29] NDAR, 11:576.

[30] NDAR, 11:543-44.

[31] NDAR, 11:837-8.

[32] Charles Biddle, Autobiography, 395.

[33] UK National Archives, Kew. ADM 36/ 8072, Muster Roll of HMS Yarmouth, June-July 1778.

[34] NDAR, 11:576.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Charles Biddle, Autobiography of Charles Biddle. 107.

[37] Todd Andrlik, “The 25 Deadliest Battles of the Revolutionary War,” Journal of the American Revolution, May 13, 2014.

[38] Don Glickstein, After Yorktown: The Final Struggle for American Independence (Westholme, 2016), 266-7.

[39] Joshua Shepherd, “A Melancholy Accident: The Disastrous Explosion at Charleston,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 5, 2015, allthingsliberty.com/2015/08/a-melancholy-accident-the-disastrous-explosion-at-charleston/.

[40] NDAR, 11:623, 666-7.

[41] UK, National Archives, Kew. ADM 36/8072, Admiralty: Royal Navy Ships’ Musters (Series I), American Prisoners on Supernumerary Allowance.

[42] UK, National Archives, Kew. ADM 34/853, Navy Board: Navy Pay Office: Ships’ Pay Books (Series II).

[43] NDAR, 12:478.

[44] The Derby Mercury, June 16, 1780.

[45] A.S. Salley, Journal of the Commissioners of the Navy of South Carolina, October 9, 1776-March 1, 1779, July 22, 1779-March 23, 1780 (The Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1912), 1:159.

[46] Mouzon, South Carolina Privateers, 24.

4 Comments

Since the main purpose for the ships of the Continental Navy was purchasing, begging, borrowing or stealing gunpowder (powder could not be made in America, where no sulfur was to be had), and it was a measure of how well they succeeded that the land forces never ran out of powder after the Continental Navy was begun, I have often wondered whether the frigate RANDOLPH had acquired additional powder on her cruise, and that is the primary reason she blew up so quickly. We will never know. Many wags back then and now have claimed that the Continental Navy was a complete waste of money because so many expensive frigates surrendered without firing a shot, but if you were loaded to the back teeth with powder, you’d surrender too!

A very good article. Nicely done. I noticed with interest that the ship’s name, Randolph, is not used in the British muster book when it picked up the four survivors, merely saying they were saved from “the wreck.” Sailor to sailor, there must have been some empathy among the British seeing what those four men had survived.

The Randolph blew up taking with it the flower of Philadelphia youth. When it was crewed there was a rush among the city’s well-to-do to enlist their sons on her. I believe one of Timothy Matlack’s sons, for instance, was one of her midshipmen. The Randolph spent most of her time in Charleston careened on her side, as it was discovered on her shakedown cruise that she yawed terribly from undergrowth/barnacles that had grown there during her extended time blockaded in Philadelphia… and her mainmast had become unseated. Some claimed that this impacted her powder, making it more volatile… but I have no idea how that would have happened. It is more likely that one of her 12 pounders burst since they had been cast domestically at either Hopewell or Cornwall Furnaces in PA, and they had a devil of a time getting their guns to prove so the customary standards were diminished.

Ed, yes Matlack’s son was reportedly a midshipman on the Randolph. That item, with many other details, did not make into the article given space limitations. Unfortunately, I did not find a ship muster or anything like it to verify who, beyond a few officers, were on the ship when it exploded. I am not certain one exists. There was a change in the crew in Charleston with some sailor leaving the ship complicating matters further. How the ship exploded will likely remain a mystery in my mind. I am not certain that the remains of the ship have been located but that would be an interesting discovery.