Borden H. Mills, writing on the Saratoga campaign a century ago, noted:

The task of determining, with any degree of certainty, what militia units actually participated in the battles or were present at the surrender is a stupendous one. All that can be done is to present the known facts and draw certain conclusions therefrom, which may, or may not, be in accordance with the actual situation then existing.[1]

Researchers have continued this quest and expanded our understanding, including Journal of the American Revolution authors Matthew Novasad, in his article on Ebenezer Lathrop’s Connecticut militia company, and Dean Snow in his article on Continental and militia cavalry.

Brig. Gen. James Brickett’s Massachusetts militia brigade was one of those organizations which challenged Mills. He concluded that it consisted of four Essex County militia regiments, identifying one as the 4th Essex County Regiment under Col. Samuel Johnson, another as a regiment of volunteers commanded by Major Charles Smith, and stated that “No evidence as to the service of any other regiments in this brigade has been found. This is unfortunate, as the brigade appears to have had a most creditable record in the campaign.”[2]

Saratoga National Historical Park historian Charles W. Snell indicated in his 1951 report on the organization and strength of American forces at Saratoga that Brickett’s brigade was composed of portions of two Essex County militia regiments, though with Smith in command of the 3rd and Maj. Benjamin Gage in command of the 4th; and two Middlesex County militia regiments, the 3rd under Col. Francis Faulkner and the 6th under Col. Jonathan Reed.[3]

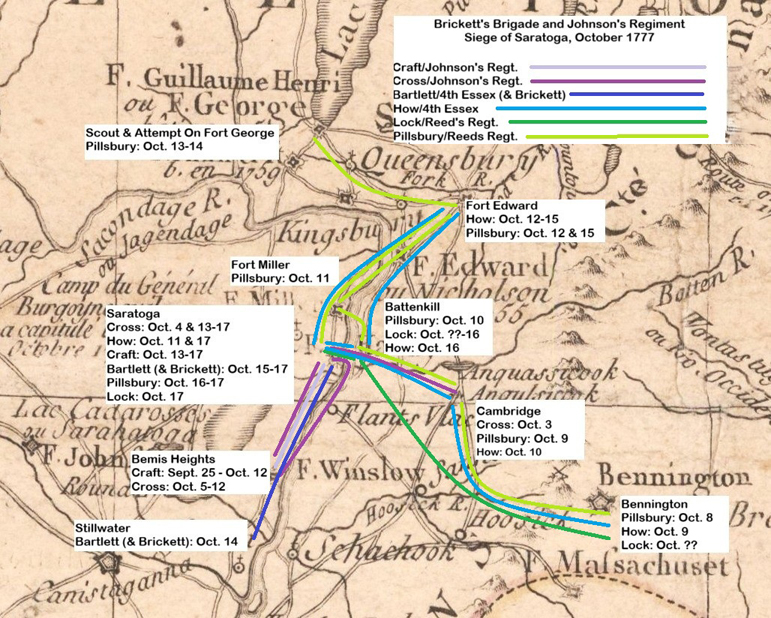

Further examination suggests that it is unclear as to what extent, if at all, Brickett exercised command over a brigade during the last few days of the Saratoga campaign. The companies of the regiments which mobilized when Brickett did in September marched separately for the most part, and arrived at Saratoga after the October 7, 1777, Battle of Bemis Heights. Widely dispersed, they took up positions on both the east and west bank of the Hudson River, and as far north as Fort Edward during the final week of the campaign. Following the surrender on October 17, three regiments escorted the prisoners, now called the Convention Army, in two separate columns from Saratoga, New York, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the barracks they would occupy in Charlestown on Prospect and Winter Hill. One regiment, though it was severely under strength, included a troop of cavalry.

Brickett, a physician, served as a surgeon in the French and Indian War. At the start of the Revolutionary War he was a lieutenant colonel in James Frye’s Essex County regiment, and was wounded at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.[4] Brickett’s appointment as a brigadier general in July 1776 led William Tudor to write to John Adams, saying: “Doctor Bricket of Haverhill who was a Lieutenant Colonel last Campaign and could not be return’d qualified for a Field Officer this, is sent by the Massachusetts in the Capacity of Brigadier General of the New Levies ordered to Ticonderoga.”[5]

Brickett’s role as a brigade commander in 1776 is well documented. He arrived at Fort Ticonderoga on August 13, and remained until November 18, when Col. Jeduthan Baldwin noted in his journal: “Genls. Gates, Arnold & Bricket left Camp.” His brigade’s arrival was noted in the general orders which directed that: “The Brigade of the Massachusetts Militia Commanded by Brigadier General Brocket [sic] is to encamp upon the high ground to the westward of the old fort of Ticonderoga. General Bricket and Colonel St. Clair will agree upon the spot, and mark out the camp accordingly.” On August 14 his brigade was ordered to detach eight officers and one-hundred and seventy men “to join and do duty with the Corps of Artillery.” Three days later it was directed to parade four of its officers and one-hundred and eight men “to take 20 Battaus to Skeenesborough,” a task they were assigned again on August 28.[6]

Brickett dined with Baldwin on multiple occasions, and went out with him at least once as he laid out defensive works in anticipation of a British attack from Canada. On October 16, Baldwin noted: “I Breakfasted with Genl. Bricket. one of our Spies came in from Crown point & Says that the Enemy were incampt. in Col. Hartleys fort & on Chimney point.”[7] On October 26, when an attack was thought to be imminent, Brickett was assigned to defend Fort Ticonderoga itself, “the Old Fort,” and its covered way.[8] In the absence of an attack, mundane matters such as court martials occupied him and his men’s time until they returned home.[9]

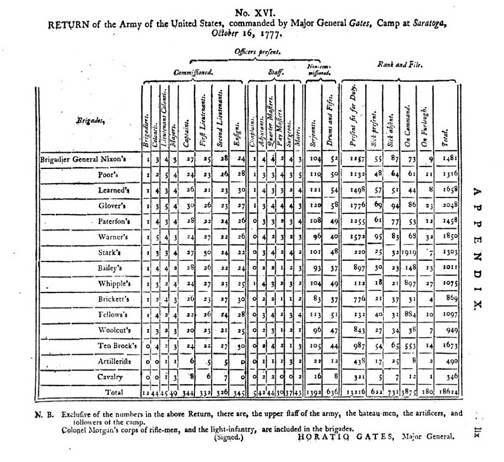

One year later Brickett served again, but with little mention of him or his brigade during the short time they were in camp at Saratoga. Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates’ return of the troops of the Northern Army at Saratoga on October 16, 1777, lists Brickett as the commander of one of the thirteen American infantry brigades present the day before the surrender.[10] The return lists the number of officers, staff, non-commissioned officers, and “rank and file” in each infantry brigade by commander, as well as the artillery and cavalry as a whole. It does not list individual regiments or companies. Mills’ conclusion that Brickett’s brigade consisted of four regiments appears to be based on the number of officers listed, “two colonels, four lieutenant-colonels, three majors and 26 captains.”[11]

Mills’ conclusions and Brickett’s strength as documented in Gates’ return raises several questions. A Massachusetts resolution passed August 9, 1777, directed that militiamen mobilized to support the Northern Army were to be organized into companies of sixty-eight men including non-commissioned officers, with one captain and two lieutenants for each company, and the resulting companies were to be “drafted into Regiments consisting of eight companies each, as near may be … [with each regiment having] one Colonel, one Lieut Colonel, one Major.” Each regiment’s field officers were authorized to appoint an adjutant, quartermaster, surgeon and surgeon’s mate, and brigadier-generals a brigade major and chaplain.[12] Under this arrangement a brigade of four regiments would be authorized four colonels, four lieutenant colonels and five majors.

Mills and Snell did not address why there were four lieutenant-colonels listed as present with the brigade when Mills concluded that at least one of its regiments, and Snell two of its regiments, were led by majors. Neither recognized that while the October 16 return lists thirty ensigns as present in Brickett’s brigade, the August 9 Massachusetts resolution did not authorize the appointment of any ensigns, and there are no ensigns recorded as having served in Smith’s, Gage’s or Reed regiments, or any of the other Massachusetts militia regiments with the Northern army under the August and September mobilizations. This calls into question the reliability of the numbers reported not only for Brickett’s brigade, but the two other Massachusetts militia brigades at Saratoga, Brig. Gen. Jonathan Warner’s which is listed as having twenty-six ensigns, and Brig. Gen. John Fellows which is listed as having twenty-eight.[13]

Mills, presumably relying on the fact that Brickett was from Haverhill, in Essex County, Massachusetts, concluded that if there were four regiments in Brickett’s brigade, “Probably all were from Essex county.”[14] Mills was mistaken in crediting Johnson with command of the 4th Essex, and Smith with command of a regiment of volunteers. It was Johnson, mobilized in August to serve until the end of November, who commanded a regiment drawn from several Essex county regiments. Smith commanded one of the two designated Essex County regiments when a September resolution specifically called for “at the least one half of all the Able bodied militia in the Counties of Berkshire, Hampshire, Worcester and Middlesex & the third & fourth Regiments of the County of Essex… [to march] to join the Army under General Gates … & to be under his Command for thirty Days after their arrival in Camp.”[15]

The 3rd Essex, under the command of Col. Jonathan Cogswell, drew its companies from the towns of Ipswich, Topsfield, and Wenham.[16] Cogswell does not appear to have served in the Saratoga campaign, and tried to resign his commission in December.[17] On October 2, 1777, Essex County’s Brig. Gen. Michael Farley notified the Massachusetts Council that he had alerted “the 3rd Essex Co. regt. commanded by said Smith, Major,” and while men from its companies in Ipswich and Wenham would serve, “not a man had responded to the call from the town of Topsfield.”.[18] Once alerted, the regiment marched with three companies, one under Capt. Richard Dodge of Wenham, who served in the Continental Army in 1775 and 1776, a second under Capt. David Low of Ipswich, and the third, a company of light horse, under the command of Capt. Robert Perkins.[19]

In September 1776 the field officers of the 3rd Essex had petitioned for the recognition of a cavalry unit as a part of the regiment, noting “That there has bin for a long Term of Time a Troop of Horse belonging to the aforesaid Regiment,” and as its members had noted voted for the officers in the regiment’s foot companies “we apprehend they will not willingly do Duty in Said Companies. And they are so Remotely Situated from each other, that they will not be able to form a foot Company with any Conveniency … and they are Desirous that they might be Allowed to Ride.”[20] Official recognition and approval for a company of not more than fifty-eight men, who would elect their captain, lieutenant, cornet and own quartermaster was granted on March 19, 1777. Each member of the company was required to have

a good and serviceable horse [and appropriate riding gear] … and further equip himself with a good carbine or firelock, not less than three feet long in barrel, with a belt and swivel, a case of good pistols, with a cutlass, a flask or cartouch-box[21]

Farley’s message specifically noted that “a troop of horse under the command of Capt Robert Perkins … marched from Ipswich, the horse Sept 30, 1777, the foot Oct 1, 1777.”[22] The Reverend Manasseh Cutler of Ipswich similarly noted in his diary that the 3rd marched on two separate days, writing:

Sept. 29, Mon. Mustering men to go the Northern Army. Half the militia called for. All the troop [Perkins company of light horse] in this town concluded to go. Sept. 30, Tues. The troop marched. They halted at Mr. John Brown’s and sent for me to pray with them. Oct. 2, Thurs. The foot [soldiers] marched.[23]

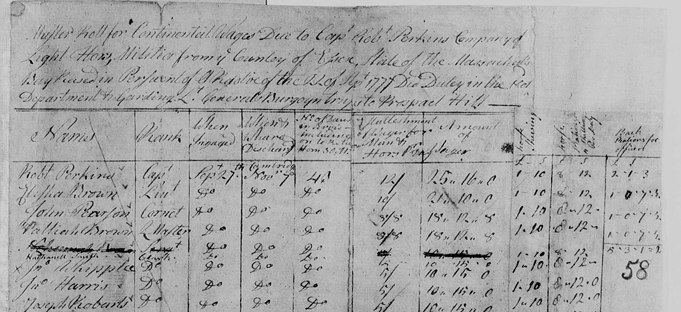

Five months after the Saratoga campaign, as no provision had been made to reimburse “any Detachm[ent] of Light Horse that has ben detached or recomm[ded] to march to reinforce the Continentall Army,” those mounted troops who had served were approved to receive the same pay and rations granted to light horse in the Continental Army.[24] A muster roll in the Massachusetts State Archives “for Continental Wages Due to Cap’t Rob.t Perkins Company of Light Horse Volunteers of the Reg’t of Militia Commanded by Maj. Charles Smith,” pictured here, includes columns for “horse Shewing,” listed for all as one pound, ten shillings regardless of rank; “horse Rations in Shilling Per Day” at eight pounds, twelve shillings each, four shillings a day for the forty-three days that they served; and “Back Rations for officers,” for Captain Perkins, Lt. Elisha Brown, Cornet John Pearson, and Quartermaster Palatiah Brown.[25]

Mills listed the 4th Essex County Regiment, under the command of Col. Samuel Johnson, as the second identifiable regiment with Brickett. Snell, likely relying on records in the Massachusetts Archives, determined that the 4th Essex was mobilized in September 1777 under Maj. Benjamin Gage. While Johnson was appointed to command the 4th Essex in 1776, the regiment he commanded in August 1777 was composed of militia drawn from several Essex County militia regiments, rather than just the 4th Essex. Two of his subordinates, Lt. Col. Ralph Cross, appointed a major in the 2nd Essex February 12, 1776, and Maj. Eleazer Crafts, chosen as major of the 6th Essex on April 24, 1777, kept journals of their service during the Saratoga campaign. Neither mentioned Johnson’s regiment being brigaded with Brickett.[26]

The 4th Essex, as mobilized in September, appears to have consisted of seven companies from the regiment’s designated catchment area: two from both Andover and Haverhill, and one each from Boxford, Bradford and Methuen. Soldiers in two companies, Pvt. David How in Capt. David Whittier’s Methuen company, and Lt. Israel Bartlett with Capt. Nathaniel Marsh’s Haverhill company, kept journals of their service and documented their arrival dates at Saratoga as October 11 and October 16 respectively.[27]

The September 22 resolution which called for the mobilization of the 3rd and the 4th Essex County regiments directed Berkshire, Hampshire, Worcester and Middlesex counties to provide “at the least one half of all the Able bodied militia,” rather than designated regiments. Snell, who like Mills concluded that Brickett’s brigade consisted of four regiments, determined that in addition to two Essex County regiments there were “portions of the following regiments: … Col. Francis Faulkner’s Third Middlesex County Regt. … [and] Col. Jonathan Reed’s sixth Middlesex County Regt.”[28]

While Reed was commissioned as the colonel of the 6th Middlesex on February 14, 1776, the regiment he commanded during the Saratoga campaign consisted of ten companies drawn from four different Middlesex County regiments, the 3rd, 4th, 6th and 7th. The regiment, consistently referred to as “Col. Reed’s” rather than the 6th Middlesex Regiment in company muster rolls, included notable and diverse personnel, but “Colonel” Francis Faulkner was not among them. Faulkner, appointed as a lieutenant colonel in the 3rd Essex in February 1776, is not listed as having served during the Saratoga campaign, and was not promoted to command the regiment until the 3rd’s original colonel, Eleazer Brooks, was promoted to brigadier-general in October 1778.[29]

Among those who did serve under Reed during the Saratoga campaign were several men who had been on Lexington Common the morning of April 19, 1775, with Capt. John Parker’s company, when the first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired. John Buttrick, who served as a major in 1775 and gave the order “Fire! For God’s sake fire!” at the North Bridge, commanded a company from the towns of Concord and Acton as a captain. William Prescott, who as a colonel was chosen to lead 1,200 men on to Bunker Hill the night of June 16, 1775, and is said to have told his men “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” served as a volunteer in Capt. James Hosely’s company from Townsend and Pepperell. Among those less well known were two soldiers in Capt. Samuel Farrar’s company, Eli Burdoo, a free black man from Lexington, and Peter Nelson, an enslaved fourteen year old from Lincoln.[30]

Mills’ statement that “the brigade appears to have had a most creditable record in the campaign” likely credits to Brickett the service of Johnson’s Regiment, which participated in the Pawlet Expedition (often referred to as “Brown’s Raid”) in September, and fought in the Battle of Bemis Heights. Johnson’s Regiment may have been included under Brickett on the October 16 return, but its attachment to his brigade (if that occurred) would have been for a few days at best. Its inclusion would account for a second colonel and three majors, and likely the twenty-six rather than nineteen captains listed, but not four versus two lieutenant colonels, or thirty ensigns. Brickett’s estimated strength, projected from identified company rosters and with Johnson’s Regiment included, would likely be several hundred men above its reported strength of 1,113.[31]

The 3rd and 4th Essex, and Reed’s Regiment, did not march until after the September raids were concluded, and did not start arriving at Saratoga until after the Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7. Cross, mobilized in August to serve with Johnson, would note that on October 5: “Arrived att our Camp att Still Water,” and Craft on October 6: “This day Col. Johnson came to camp from Tye. we now joined our Regiment.”[32] The following day, Johnson and his men fought at Bemis Heights. Cross wrote in his journal that on October 7, “Att Noon all the Whol Camp was ordered to Arms … Coll Johnson with one halfe the Regiment was ordered to march & my selfe with Major Crofts with the Rest halfe … We Lost in our Regiment 10 Kill’d & 34 Wounded.” Craft’s entry for the day noted:

our Regiment was ordered to the rear of Col. Poor’s Brigade … We marched out of our lines about 4 o’clock … we all eagerly ran to the field, but were soon met by a shower of grape shot and small arm ball. Capt. Flint fell close by me the first minute we got up.[33]

After the battle, when Gates initiated his pursuit of Burgoyne’s retreating army on October 10, Craft noted that their regiment was one of three that remained behind.[34] Cross, who was assigned to break up the British bridge of boats, noted that on October 11 and 12 he transferred baggage and stores from Stillwater and the American camp to Saratoga, and then October 13 marched from Bemis Heights to Saratoga, “1/2 miles Short of the Me[e]ting House & Encamp’d & one mile from the Enemies Lines,” where they stayed until October 18, when they received orders to march to Albany.[35]

It is questionable as to what degree, if any, Brickett exercised command over the regiments attributed to his brigade during the Saratoga campaign. The regiments arrived at the front piecemeal, and were dispersed across the area of operation, well away from their nominal brigade commander. Brickett, traveling with Marsh’s company of the 4th Essex County regiment, left home October 4 and did not reach Stillwater, New York, until October 14, a week after the battle and the day after Cross and Craft had left.[36] On October 15, two days before the surrender and with a ceasefire in effect, Bartlett recorded that their company “Marched and arrived at Head Quarters at 12 O’clock. Encamped in the Woods – Good House & Grand fire,” and remained at Saratoga, on the west side of the Hudson River, until October 18 when they were ordered to “march in order to take charge of the prisoners, who are to march to Boston.”[37]

When Brickett arrived at Saratoga, companies from at least two of the regiments attributed to his brigade were positioned on the east side of the Hudson River, as far north as Fort Edward. In Reed’s Middlesex Regiment, Benjamin Lock, with Capt. Samuel Farrar’s company, noted in his journal that after passing through Cambridge, New York, he went to “head quarters att Saratoga” and camped at “a place cald Batenrill.”[38] Buttrick’s company “arrived at Saratoga on the 10th, where they encamped two days. The 13th they went to Fort Edward. The 14th and 15th, went out on a scout, and the 16th brought in fifty-three Indians, several Tories (one of whom had 100 guineas), and some women.”[39] Joshua Pillsbury, with Capt. Joseph Varnum’s company, arrived at Fort Edward on October 12. On October 13 he recorded “Skoouted towards the Lake and Brought in Several prisoners,” and the next day “Marched and Skooute to Lake George to Take the Fort but could not,” so they returned to Fort Edward on October 15.[40] How, with the 4th Essex, wrote in his diary that he too arrived at Fort Edward on October 12, remained there until October 15, noting that day: “This morning our Scouts Brought in upwards of 50 Indians that ware made prisoners Yesterday Near Fort George,” and on October 17, “This morning we march’d To Salletoga with all the Reg’t.”[41]

Following Burgoyne’s surrender on October 17, General Gates notified the Massachusetts Council:

I have the Pleasure to send your Honourable Council, the inclosed Copy of a Convention, by which Lieutenant-General Burgoyne, surrendered himself, and his whole Army, on the 17th Instant, into my Hands; they are now upon their march towards Boston; General Glover, and General Whipple, with a proper Guard of Militia, escort them[42]

Brickett’s men, all from eastern Massachusetts, and with just three weeks left to serve, were ideally suited to escort the five thousand or so British and German troops on their march to Boston under the terms of the Articles of Convention.

Even during this period, Brickett’s role as a brigade commander was limited. Once the Convention Army was across the Hudson, the British and German columns traveled on two separate routes until they reached Western, now Warren, Massachusetts. Brig. Gen. John Glover wrote in 1780 that Brickett commanded “about five Hundred Militia … to Guard a Division of the Convention Troops from Saratoga to Cambridge – which charge he executed with Judgement and Prudence.”[43] A German officer noted, “On order of Colonel Reid [Reed], a militia regt. was to escort the German corps.”[44] Johnson’s Regiment, obligated to serve until November 30, was not with them. Cross noted the regiment received orders at noon on October 18 to march for Albany, where they halted for four days, and then after stopping two days because he was ill, he reached the Catskills on October 29, “where I found the Whole Brigade with Gen. Warner.”[45]

British Ens. Thomas Anburey would later write “We were escorted on our march by the brigade of a General Brickett,” who he said, “was very civil, and often used to ride by the side of the officers, to converse with them.” At some point, when a British officer mentioned to Brickett that he was uncomfortable for want of a pair of boots, Brickett offered to sell him the ones he had on, but only for gold, not paper money. Offer accepted, Brickett immediately dismounted and had to be convinced to wait until they reached their quarters that night to complete the bargain, leading Anburey to conclude “So much for an American Brigadier-General”.[46]

Regardless of Anburey’s slight, Brickett and his men were part of the influx of thousands of militia into the Northern Army who provided Gates with a robust force to block Burgoyne’s escape and force his surrender. The October 16 return provides a starting point for understanding the composition of the brigade attributed to him: the 3rd Essex, with its volunteer light horse troop; the 4th Essex under its major, serving separately from Johnson’s Regiment; and a hybrid regiment from the Middlesex militia formed from available personnel, best referred to as “Reed’s” rather than the “6th” Middlesex County regiment.

[1] Borden H. Mills, “Troop Units at the Battle of Saratoga,” The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association, 9, no. 2 (1928), 144.

[2] Ibid, 148.

[3] Charles W. Snell, “A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’ Army …” (Saratoga National Historical Park, 1951), 29-30. Brickett’s name appears to have been first typed with an “s”, then struck over with a “c.” This has led some authors to misspell Brickett’s name as “Briskett.”

[4] George Wingate Chase, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts (Haverhill, MA: Published by the Author, 1861), 623.

[5] William Tudor to John Adams, August 19, 1776, Massachusetts Historical Society, “Adams Papers Digital Edition,” www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/ADMS-06-04-02-0220.

[6] Doyen Salsig, ed., Parole: Quebec; Countersign: Ticonderoga, Second New Jersey Regimental Orderly Book, 1776 (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1980), 202-203, 210, 222.

[7] Thomas Williams Baldwin, The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin (Bangor, ME: Printed for the DeBurians, 1906), 70-86.

[8] Salsig, Parole: Quebec; Countersign: Ticonderoga, 274.

[9] Robert O. Bascom, Orderly Book of Capt. Ichabod Norton of Col. Mott’s Regiment (Fort Edward, NY: Keating & Barnard, 1898), 45.

[10] John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition From Canada, as Laid Before the House of Commons (London: J. Almon, 1780), Appendix lix.

[11] Mills, “Troop Units at the Battle of Saratoga”, 148.

[12] “Chapter 222 – Resolve For Drafting One-Sixth Part Of The Militia To Reinforce The Continental Army,” August 9, 1777, The Acts And Resolves Public And Private Of The Province Of The Massachusetts Bay (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1918), 20:88-90.

[13] A search for ensigns serving with a Massachusetts militia regiment at Saratoga in Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the American Revolution returns only one, Oliver Barron of Chelmsford, who is listed as a “Captain, serving as Ensign” in Capt. John Ford’s company of Reed’s regiment. (Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the American Revolution (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1897), 1:691.) This appears to be an error. A transcription of the muster roll for Ford’s company lists Barron under the heading of “Privates,” as “Esq.,” (esquire), not with the rank of ensign, and indicates he was being paid at the rate of two shillings a month, as were all of the other privates in the company. Wilson Waters, History of Chelmsford Massachusetts (Lowell, MA: Printed for the Town, 1917), 262.

[14] Mills, “Troop Units at the Battle of Saratoga,” 148.

[15] “Chapter 307 – Resolve Providing For A Reinforcement To The Northern Army,” September 22, 1777, The Acts And Resolves Public And Private Of The Province Of The Massachusetts Bay (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1918), 20:125-126.

[16] “List of the Field-Officers of the several Regiments of Militia in this Colony, as chosen by the House,” digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A106148.

[17] Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the American Revolution (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1897), 3:722.

[18] Muster Roll Index Card of Charles Smith, Massachusetts State Archives. Accessed through FamilySearch at: “Alexander, Alexander, Washington, Massachusetts, United States records,” www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSQZ-JSP7-5?view=explore, Image Group Number 007843811, images 548 and 549 of 3044.

[19] Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the American Revolution, 4:834; 9:1023-1024; and 12:168.

[20] “Notes Chapter 33,” The Acts And Resolves Public And Private Of The Province Of The Massachusetts Bay (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1886), 5:696.

[21] Ibid, “Chapter 33 – An Act For Raising And Forming A Company Or Troop Of Horse In The Third Regiment Of Foot In The County Of Essex,” March 19, 1777, 5:621-623.

[22] Muster Roll Index Card of Charles Smith, Massachusetts State Archives. Accessed through FamilySearch at: “Alexander, Alexander, Washington, Massachusetts, United States records,” www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSQZ-JSP7-5?view=explore, Image Group Number 007843811, images 548 and 549 of 3044.

[23] William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler, Life Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D (Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co, 1888), 1:63-64. Cutler’s diary entry for November 7, which states: “About 12 o’clock Burgoyne came into town, attended by a party of the American Light Horse as a guard” supports the claim that Burgoyne was escorted from Saratoga to Cambridge by Continental cavalry. Cutler is unlikely to have confused militia cavalry from his community who he prayed with a month earlier with Continentals.

[24] “Chapter 872 – Resolve Establishing Pay And Rations Of Detachments Of Light Horse,” March 11, 1778, The Acts And Resolves Public And Private Of The Province Of The Massachusetts Bay (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1918), 20:327.

[25] “Muster Roll for Continental Wages Due to Cap’t Rob.t Perkins Company of Light Horse Volunteers of the Reg’t of Militia Commanded by Maj. Charles Smith,” Massachusetts State Archives, accessed through FamilySearch at: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSJ7-C97B-P?lang=en&i=115, Image Group Number 00784381, image 116 of 682. New Hampshire militia Brig. Gen. William Whipple noted in his journal that he paid nine shillings to shoe his horse in Exeter, New Hampshire, en route to Saratoga. William Whipple, Memorandum and Expenses, Burgoyne Campaign, 1777, Portsmouth New Hampshire Athenaeum, John Langdon Papers, Catalog Number MS050 B08 F36.

[26] Pvt. Ezra Ross of the 3rd Essex County regiment also served under Johnson. Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 12:583. Ross, ill on his return home, stopped in Brookfield, Massachusetts. There, he had an affair with Bathsheba Spooner, then conspired with her and two British deserters from the Convention Army to murder her husband on March 1, 1778. All four were arrested within a few days, tried, and hung in Worcester, Massachusetts on July 2, 1778. 1777march.blogspot.com/2023/07/july-2-1778-three-revolutionary-soldiers.html.

[27] Henry B. Dawson, Diary of David How (Cambridge, MA: H.O. Houghton, 1865), 47. Chase, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, 401.

[28] Snell, “A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’ Army,” 29-30.

[29] For Reed, see: Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 13:77. For Faulkner, ibid, 5:564. For Brooks, ibid, 2:572.

[30] Benjamin Wellington, who claimed to be the first armed American taken in the Revolution on April 19, 1775, was among those from Lexington. (Charles Hudson, History of The Town of Lexington (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913), 2:730.) For Buttrick, www.nps.gov/people/major-john-buttrick.htm; for Prescott, www.nps.gov/articles/000/william-prescott.htm; for Burdoo, www.nps.gov/people/eli-burdoo.htm; for Nelson, www.nps.gov/articles/000/massachusetts-1777-peter-nelson.htm.

[31] Snell indicates that Johnson had 472 men in his regiment, but is not clear as to how he came to this conclusion. Using an average company size based on known numbers across the 3rd and 4th Essex and Reed’s regiment where actual numbers are missing, Brickett’s brigade would number just over 900 men without Johnson, and almost 1,400 with Johnson. This difference may be due to where some of Brickett’s men were on October 16.

[32] Joseph Williamson, ed., “The Journal of Ralph Cross, of Newburyport, Who Commanded the Essex Regiment, at the Surrender of Burgoyne, in 1777,” The Historical Magazine, Second Series 7, no. 1, (1870), 10. James M. Crafts and William F. Crafts, The Crafts Family (Northampton, MA: Gazette Printing Company, 1893), 690.

[33] Williamson, “The Journal of Ralph Cross”, 10. Crafts, The Crafts Family, 690.

[34] Crafts, The Crafts Family, 691. The editors state the regiments which remained behind were under a general named “Varnum,” but Brig. Gen. James Varnum of Rhode Island was not at Saratoga.

[35] Williamson, “The Journal of Ralph Cross,” 10-11.

[36] B.L. Mirick, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts (Haverhill, MA: A.W. Thayer, 1832), 180.

[37] Chase, History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, 401.

[38] Benjamin Lock, “My March From Home into the army in ye year of our Lord King Hancock 1777,” National Archives Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File S. 18492, for Benjamin Lock, Massachusetts, catalog.archives.gov/id/196193964?objectPage=35. Lock was at the confluence of the Battenkill Creek and the Hudson River. Whipple and his brigade of New Hampshire militia were posted there October 10. Two field pieces which arrived that night were sent on to Fort Edward the following day. William Whipple, Memorandum and Expenses, Burgoyne Campaign, 1777, Portsmouth New Hampshire Athenaeum, John Langdon Papers, Catalog Number MS050 B08 F36.

[39] Lemuel Shattuck, A History of the Town of Concord (Boston, MA: Russell, Odiorne, and Company, 1835), 356.

[40] Ray W. Pettingill, “To Saratoga and Back,” The New England Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1937), 787.

[41] Dawson, Diary of David How, 48.

[42] Horatio Gates to the Massachusetts Council, October 19, 1777, Albany, New York. The Independent Chronicle and Universal Advertiser (Boston, MA), October 23, 1777; Boston Gazette, October 27, 1777.

[43] Frank A. Gardner, MD, “Colonel James Frye’s Regiment,” The Massachusetts Magazine, 3, no. 3 (1910), 195-196.

[44] Helga Doblin, trans., The Specht Journal (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), 102.

[45] Williamson, “The Journal of Ralph Cross,” 11.

[46] Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America (New York: Arno Press, 1969), 2:53-54.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...