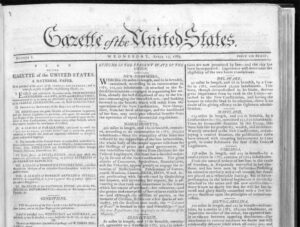

Many Americans celebrated April 30, 1789, as a defining moment for the United States, a sort of political BC/AD demarcation point in the republic’s short history.[1] Once the initial jolt of national optimism and political unity induced by President George Washington’s first inauguration had worn off, however, the first administration took up the thankless business of governing.[2] A range of pressing internal and external crises faced the challenged nation, including: (1) Native unrest in nearly every direction; (2) continued British occupation of the Northwest, parts of New York and around Lake Champlain; (3) Spanish antagonism on the Mississippi River; (4) Algerian pirates threatening American mariners in the Atlantic; (5) general European commercial hostility; and, (6) the alarming state of American debt and credit.[3] Yet governance under the new Constitution ostensibly placed the reins of power into more capable hands, allowing federal statesmen to make sense of the tangled trail of trouble suffocating the infant nation.[4] To communicate the success of the new constitutional order and its administrations, editor John Fenno of Boston relocated to the seat of government to publish the Gazette of the United States. He had hoped to educate Americans on the major issues facing the republic and, by projecting reverence of the Constitution and deference to federal union and its leaders and laws, create an American national identity and bind the union.[5] It did not take long for some Americans to perceive the shadow of monarchy in Fenno’s agenda.

During that brief moment of national cohesiveness, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson saw little in John Fenno’s gazette to give him pause. In fact, the secretary even patronized that editor with several generous printing contracts.[6] Yet during the second year of the Washington administration, Jefferson had become increasingly alarmed by what he described as internal “enemies of the government,” designing men who aimed to revert the republic back “into a monarchy.”[7] Among the issues that raised Jefferson’s suspicions were Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s proposals to charter a bank of the United States and have the national government assume all state debts and fund the national debt. From Jefferson’s perspective, not only were Hamilton’s advances disastrous policy favorable to northern elites; they conspicuously aimed to consolidate government authority at a central point, reminiscent of the old monarchical system. These initiatives found dedicated support in the pages of Fenno’s newspaper, along with frequent recommendations that citizens defer to national leaders and legislation.[8] In time, Jefferson came to see Fenno’s publication as dangerous monarchical propaganda.

Jefferson believed the national interest demanded a counterpoint to Fenno’s “paper of pure Toryism.”[9] He and protégé James Madison found a solution in New Jersey poet Philip Freneau.

* * *

Freneau’s earliest biographer, Lewis Leary, described that poet as a “young radical who never [forgot] his quarrel with a world which [made] no room for him.”[10] In fact, Freneau’s adventurous life embodied generations of his family’s daring escapades. He descended from French Huguenots, a persecuted people who fled from France to Britain before settling in the American colonies. Pierre Freneau, the poet’s father, found success trading lumber and Madeira before moving to Monmouth, New Jersey.[11] Pierre and wife Agnus welcomed Philip and his siblings into their home, which the couple outfitted with a robust library. The Book of the Common Prayer, The Works of the Late Reverend Isaac Watts, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare and editions of The Spectator initiated Freneau’s literary life, likely under the careful tutelage of Agnus. He may have attended a boarding school in New York, but by fifteen had certainly studied under Alexander Mitchell at Mattisonia Grammar School in Monmouth. Mitchell, a graduate of the College of New Jersey (Princeton), guided Freneau through Horace, Cicero and the Greek Testament while assisting the boy in English and Latin composition. Freneau’s father had wished for his eldest son to join the clergy, so the youth’s early schooling also included the necessary theological dimension. The College of New Jersey accepted Philip the following year, impressed enough with the sixteen-year-old’s erudition to let him begin his studies as a sophomore.[12]

At university, Freneau attended to, among others, John Milton, Francis Bacon, Joseph Addison, Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and Homer. He also formed close bonds with some fellow students, including Virginia aristocrat James Madison, Pennsylvania Scotchman Hugh Henry Brackenridge and Philadelphia’s William Bradford. This diverse collection of youths started the radical American Whig Society, a club animated by, according to scholar Lewis Leary, patriotism. Leary claimed it defended “every liberal and humane ideal” against the “Tory” Clio-Sophic Club.[13] These collegiate associations, nominally literary fraternities, actually served as platforms to argue contemporary politics, the American Whig Society defending the colonial position while (at times inaccurately) accusing their opponents of supporting Parliament during the deepening imperial crisis. It was during Freneau’s college years that he also began to blossom as a poet of some promise, his much-acclaimed “The Rising Glory of America” a testament to this observation.[14] It seems clear that, at this point in Freneau’s life, he had drifted from preparing for the clergy and gravitated toward poetry.

Shortly after graduating, Freneau moved to Philadelphia, possibly to study for the bar, and took note of the antislavery movement championed by men such as Dr. Benjamin Rush and French educator and abolitionist Anthony Benezet.[15] With few opportunities in that city, he moved yet again, finding employment as a teacher in Long Island, New York. Venting to college friend James Madison, Freneau explained that the “youth of that detested place, are void of reason and of grace,” before characterizing their parents as bullies, merchants “and other Scoundrels.” Freneau lasted thirteen days at that school before fleeing under the proverbial cover of night. The experience left him so traumatized that he composed the appropriately named poem, “The Miserable Life of a Pedagogue.”[16] Yet he returned to teaching in 1772 while finally trying his hand at becoming an Anglican minister. This time Freneau landed in Maryland, where his old friend Hugh Brackenridge presided as master of Somerset Academy at Back Creek. Brackenridge extended an offer to the poet to teach and the latter, likely desperate for a little money and stability, accepted. Recognizing his own impulsive and rather directionless nature, Freneau worried openly over what would satisfy his “‘giddy’ wandring brain.” In a letter to Madison, Freneau described himself as looking like an unkempt Irishman who survived a journey across the Atlantic. “My hair is grown like a mop, and I have a huge tuft of a Beard directly upon my chin.” Already cognizant of the miles of his years, he admitted “I Want but five weeks of twenty Years … and already feel stiff with age.”[17] He eventually quit Somerset and landed back at New York in early 1775.[18]

As the empire’s political turmoil grew increasingly violent, Freneau penned numerous poems defending American liberty and condemning alleged British oppression. “From a Kingdom that bullies, and hectors, and swears,” the poet howled, “We send up to heaven our wishes and prayers.”[19] As pointed out by scholar Jacob Axelrad, Freneau’s artistic efforts served more as patriotic propaganda than poetry.[20] “The New Liberty Pole—Take Care,” “Libera, Nos, Domine,” “American Liberty,” and “General Gage’s Confession” are but a sampling of the poems he wrote in response to the unfolding revolutionary drama. Whether poetically punishing loyalists, castigating British arrogance, venerating American freedoms or even satirizing a literary conviction of Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage for so-called crimes against humanity, Freneau’s verse championed the Whig cause.[21] But as war came, puzzlingly, Freneau boarded a vessel out of the British Empire and into what he had hoped would be a poet’s paradise.

Freneau embraced the unknown and embarked upon an adventure beginning at St. Croix in early 1776.[22] Both impressed by that island’s beauty and horrified by its brutal slave regime, Freneau passed his time in a sort of moral purgatory. His poetry from this period offers a stinging indictment of slavery and man’s insatiable desire to ruthlessly pursue wealth at all costs, yet he also partook of the island’s pleasures.[23] He kept abreast of American news, learning of the Declaration of Independence as well major military developments.[24]

Freneau returned to New Jersey in 1778, expressing horror and outrage at the death and destruction the British had wrought upon his childhood community. He joined the First Regiment of the New Jersey Militia, led by Colonel Asher Holmes, to protect the shorelines from further enemy deprivations.[25] Freneau’s poetry transformed as well, and, as observed by Jacob Axelrad, he began writing “for fighting men more than for critics.” He resigned from the militia to captain several vessels, patrolling the Caribbean for British prizes. While acting as third mate on the Aurora, his ship surrendered to a British warship and he found himself a captive. Freneau remained prisoner of war for six months, stuffed below deck of the prison ship Scorpion. Freneau memorialized his harrowing experience in perhaps his most famous work, the “British Prison Ship.”[26] After recovering at home, he began writing for a newspaper before spending another year at sea. The restless poet married Eleanor Forman and the couple settled in New York, Philip once again returning to the press in 1790.[27] His financial troubles only worsened as he and his wife prepared for their first child.[28]

* * *

As the Washington administration wrestled with political legitimacy, implementing Hamilton’s financial system and determining how to respond to the French Revolution, a shaken Madison and Jefferson plotted to recruit a dependable Republican to combat John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States. Jefferson condemned that paper “for its Toryism and its incessant efforts to overturn the government.”[29] Madison hoped a rival paper would act as an “antidote to the doctrines and discourses circulated in favour of Monarchy and Arastocracy.”[30] In similar language, Jefferson recognized the partisan utility of establishing a “whig vehicle of intelligence” to combat the “doctrines of monarchy [and] aristocracy” allegedly found within Fenno’s gazette. The secretary also remained alarmed by that editor’s perceived “exclusion of the influence of the people.”[31] Impressed with some of Philip Freneau’s work for the New York Daily Advertiser, the secretary reached out to the poet. Freneau already knew Madison, had written popular verse supportive of the American cause, fought for independence, and had also become suspicious of the Washington administration’s objectives. To Jefferson and Madison, Freneau held every qualification necessary to defend what they considered republican principles. It helped that both men estimated Freneau as intellectually brilliant.[32] In February 1791, Jefferson, who had never met Freneau, sent the poet a job offer. Almost certainly there was some other form of contact that involved Freneau directing a newspaper, as Jefferson wrote a very cryptic first letter. Reading between the lines makes it clear that Freneau must have known what Jefferson was getting at. Jefferson explained:

The clerkship for foreign languages in my office is vacant. The salary indeed is very low, being but two hundred and fifty dollars a year: but also it gives so little to do as not to interfere with any other calling the person may chuse, which would not absent him from the seat of government. I was told a few days ago that it might perhaps be convenient to you to accept it. If so it is at your service. It requires no other qualification than a moderate knowledge of the French.[33]

Clearly “any other calling” is code for newspaper editor. And equally clear, if there had been no prior communication, Freneau would have had no idea what exactly Jefferson was alluding to. Regardless, Freneau ultimately declined the offer.[34] Yet Madison and Jefferson both traveled to New York to pressure Freneau to come to Philadelphia. After initially refusing both attempts, the poet agreed to take on the endeavor if Jefferson and Madison met several demands. Freneau would relocate and edit a gazette if (1) Francis Childs of the Daily Advertiser paid for the undertaking, (2) partner John Swaines agreed to print the paper, (3) Freneau received one third of the profits (should any materialize) and (4) Freneau suffered no losses (should any accrue). Madison and Jefferson agreed to every point and, shortly afterward, Freneau relocated to Philadelphia. The Virginians finally had their editor and, at long last, Republicans had their paper, the National Gazette.

The newspaper war that unfolded during the first Washington administration may have had national implications, but the two rival printers actually labored just several blocks from one another.[35] Two dedicated philosophers, both at Philadelphia, offered the reading republic competing interpretations of American politics that reverberated from Massachusetts to Georgia, shaped partisan opinion and quickened the formation of the first party system. Jefferson, excited by recent developments, informed confidant David Humphreys about the new publication. “I shall soon be able to send you another newspaper written in a contrary spirit to that of Fenno,” he revealed, as “Freneau is come here to set up a National gazette, to be published twice a week, and on whig principles.” Jefferson then proudly announced “The two papers will shew you both sides of our politics.”[36] Madison and Jefferson further aided Freneau by encouraging subscriptions; even Madison’s father aided in this effort, volunteering to collect dues in Virginia’s Orange and Culpepper counties. Other elite Virginians, including, incredibly, the governor, aided in collecting payments.[37] Jefferson even replaced Benjamin Franklin Bache’s reliably republican Aurora with Freneau’s National Gazette in his newspaper exchanges with his daughter and son-in-law.[38] He reasoned that “Freneau’s two papers contain more good matter than Bache’s six.”[39] Madison contributed further by writing a series of essays for the publication.[40]

Philip Freneau’s paper did not announce a grand mission statement like Fenno’s Gazette of the United States. The first edition of the National Gazette arrived on October 31, 1791, and modestly promised to provide all necessary foreign news, cover congressional sessions and report any pertinent domestic developments. Yet the first domestic development Freneau addressed with force was Hamilton’s Funding and Assumption Plan. From the first edition, Freneau began chipping away at the veneer of majesty Fenno had labored to construct for national statesmen and laws. Hamilton, guided by corrupted “Machiavellian principles,” one writer warned, had devised a system to render American farmers dependent on scheming speculators and unscrupulous financiers. If Americans “wished to preserve their liberties,” he admonished, “they should avoid European systems of finance, and above all, never fund their public debt.”[41] Pseudonymous contributor “Farmer” agreed, condemning Hamilton’s fiscal initiatives as “wretched and oppressive policy.” The “yeomanry of America should be attentive to their critical situation,” he cautioned. True statesmen, he lectured, do not aim to “promote the grandeur of monarchy, or the power and influence of an aristocracy; but what will contribute to the happiness of the People.”[42] “Brutus” claimed that Washington’s “bad administration” was “undermining th[e] republican principles” of the American Revolution and encouraging “the underserving speculator.” He described Hamilton’s financial plans as “pregnant with evil” and designed to “aggrandize the few and wealthy, by oppressing the great body of the people.”[43] The following week he again denounced “active partizans of fiscal arrangements” for granting the Treasury Department “new assumptions of power.”[44] Each of these commentators accused the Washington administration of catering to moneyed elites while eroding general republican liberty. Critics also attacked other elements of Hamilton’s vision.

Hugh Henry Brackenridge published “Thoughts on the Excise Law, so far as it Respects the Western Country,” which offered a sympathetic survey of the young nation’s underdeveloped western region. The excise, he reasoned, fell particularly hard on western distillers, considering the difficulty of transporting goods to market, lack of access to the Mississippi River and general ravages of frontier violence. He blamed short-sighted wealthy men, “the germ of aristocracy,” for destroying “simplicity and true republicanism” while threatening western liberty. “Let the tax be suspended,” he pleaded.[45] Another writer condemned Hamilton’s Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures, attacking the government for promoting one interest above another, in this case industry over agriculture. American manufactures required national subsidies in the form of “bounties, premiums, and a variety of exclusive privileges” to survive, a form of federal assistance denied to small shopkeepers and farmers, he observed.[46] Unsettled by the prohibitive cost of shares for the Bank of the United States, “A Spectator” cautioned Americans to be on guard for “those who unceasingly praise and puff all the public measures which tend to raise the few into splendid opulence and generate monarchical and corrupt principles and habits.” He demanded bank subscribers be publicized so the public might learn which of them grew wealthy from their connection to government.[47] Far from demanding deference to national statesmen and their so-called wise policies, Freneau’s paper openly challenged both, normalizing dissent to national directives. It also provided sympathetic coverage of local actors and actions.

One observer urged for better roads to promote safer travel and circulate “newspapers through the entire body of the people.” This writer next advised national figures to return to their respective districts frequently to acquaint themselves with constituents and understand their needs and concerns to govern more effectively.[48] This is, not surprisingly, the inverse of what Fenno’s gazette expected of national leaders. The “opinions of the constituents,” wrote “A Friend of the Union,” in the Gazette of the United States, should “have little or no influence in legislation.” National figures brought “facts respecting the situation and interests of his constituents,” he counseled, but calculated the needs and concerns of the entire republic before crafting federal law.[49] Any eighteenth-century observer could extrapolate the ideological difference between these two positions: Republicans felt local people ought to instruct national figures and Federalists felt national leaders ought to legislate for the good of the whole nation rather than any of its specific parts. In other words, the former felt locals should send national representatives to Philadelphia to defend their interests and the latter expected national representatives to go to Philadelphia to learn before legislating.

Freneau also made certain to provide coverage of local assemblies governing responsibly. For example, he reported that the Pennsylvania legislature was considering constructing a canal to connect the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, while the Virginia legislature organized a lottery to fund an exploratory mission to “the southern parts of the United States . . . to the Gulph of Mexico.” This effort, Freneau revealed, “is carried on by the patronage of the state government, where it is frequently inspected by its officers, to prevent any errors or misinformation to the public.”[50] Both of these efforts revealed to readers initiatives that state governments engaged in to benefit local and potentially national interests. Another writer explained that the Washington administration’s use of the general welfare clause to charter the Bank of the United States ought to terrify every American. “Does not this doctrine . . . knock down every boundary between the general and state governments, and give infinite supremacy to the general government,” he bellowed. By this logic, he theorized, a president could employ the general welfare clause for any whim or desire and consolidate all authority at the national level. Americans ought to fear Federal power and guard against national encroachments on local autonomy, he urged.

Philip Freneau’s paper reported federal developments as a matter of course, but without the constant pomp and pageantry of Fenno’s paper. And when Freneau placed state and local developments alongside national news, he elevated the former to the importance of the latter for his readers. By normalizing skepticism of national men and initiatives and empowering local actors and directives, he urged his audience to remain vigilant of what many considered power’s relentless assault upon liberty. This form of coverage may very well have conditioned some Americans to see a dangerous conspiracy afoot; a designing cabal of elite Federalists intent on burning the federal Constitution and establishing a monarchy on its ashes. And Freneau provided plenty of space for conspiratorial thinking in his mission to instill political vigilance in his readers.

One writer warned that “Monarchy has always . . . [been] fascinating to a great part of mankind.” If Americans failed to check the present monarchical impulses threatening the republic, he predicted, “the cause of liberty will be abandoned, and mankind” will be condemned to idle “under the dominion of a tyrant.”[51] Another observer chastised Americans for lapsing into a “cold phlegmatic indifference” after the American Revolution. Since the close of the late war, he cautioned, “certain political magicians” had been at work convincing citizens that “the multitude of any nation” had no role to play in governing. Elite men gifted “by some supernatural means,” he darkly jested, claimed the exclusive right to govern.[52] His mention of the supernatural almost certainly is an allusion to the divine right of kings, the antithesis of the republican cause. Thus lackadaisical Americans, he reasoned, must awaken from their complacency and remain vigilant lest monarchy might corrupt republican purity.

Freneau condemned monarchies for keeping their subjects in ignorance. In comparison, an informed “representative republic,” he marveled, chooses its public servants. In order to secure liberty, “every good citizen will be at once, a centinel over the rights of the people” and challenge any expansion of federal authority. In another essay, Freneau urged Americans to be cognizant of the “imperceptible advances [of] tyranny” and “machinations of ambition.” Unless citizens remained vigilant, he claimed, the people will be crushed “by a succession of tyrants.” If Americans continued to permit the federal government to dominate the states, he later advised, the nation will be on “the high road to monarchy,” and there was “nothing worse, in the eye of a republican.” Citizens must be watchful, he pleaded, and consider the internal partitions and checks inherent in their constitutions as “the most sacred part of their property.”[53] In this essay, Freneau praised the carefully calibrated relationship between the branches of both the national and state governments and warned of national encroachments on state prerogatives. He also reminded the public of their solemn responsibility to guard against this form of dangerous consolidation.

Contributor “Caius” claimed republican principles were under attack by both ambitious men “cloaked in the garb of ministerial systems” and “a bold and persevering aristocracy.” Combined, designing parasites and haughty elites aimed to pollute the vibrant American Constitution with “all the vices, and infirmities, of the decayed, expiring constitution of Britain.”[54] Caius effectively argued that Hamilton’s financial system was enriching a corrupt cabal who owed their riches and influence to their self-interested attachment to government. And obvious aristocrats like Hamilton (and presumably even a tacitly complicit Washington) openly designed such policies to connect obedient leeches to their vision of the republic by strategically doling out sinecures. Terms like “ministerial,” “aristocracy,” “decay” and “vices” all wreaked of monarchy’s wretchedness for eighteenth-century Americans. Still another observer feared the Washington administration pursued “the most barefaced efforts . . . to substitute, in room of our equal republic, a baneful monarchy.” The national debt, for this writer, was “a monster, from whose foetid bowels proceed monarchy, aristocracy, and slavery.”[55]

Philip Freneau, watchman of liberty and guardian against despotism, hoped to awaken Americans to the constant threat power posed to liberty. Republican government, he reasoned, required vigilance in the face of such blatant internal threats. His paper’s constant skepticism toward the national government and conspiratorial diatribes against monarchy agitated Federalists, who grew alarmed by his apocalyptic view of American politics. Freneau’s gazette so unnerved President Washington that he, according to Jefferson, “got into one of those passions when he cannot command himself” at a cabinet meeting. The president, tired of the opposition press accusing him “with wanting to be king,” raged “that rascal Freneau” sent him three papers a day “as if he thought [Washington] would become the distributor of his papers.”[56] Freneau’s prose had not only enraged his opposition, it ignited the untamed temper of the American Fabius.

Philip Freneau published his gazette for about two years, his Philadelphia press going silent on October 27, 1793.[57] A few circumstances conspired to bring this about. Freneau, dedicated critic of the Washington administration, actually began to alienate his readers during the Citizen Genét Affair. France had sent minister Edmund-Charles Genét to the United States with letters of marque and commissions from the French government. When he arrived in South Carolina, he began recruiting Americans for the French struggle against Britain rather than presenting himself to President Washington. His blatant disregard for Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation was an affront not only to the president, but to the dignity of the nation. Even Republicans came to realize Genét’s actions were bad politics.[58] Yet Freneau’s gazette supported the Frenchman’s efforts, much to the dismay of some key supporters; many began canceling their subscriptions. And when Freneau’s printers began losing money over the scandal, they pulled their support. All of this happened, sadly, as the 1793 yellow fever epidemic decimated Philadelphia, leaving in its wake streets strewn with the dying, dead and decaying. The poet claimed he may start his press again with more advanced equipment from Europe; he did publish more papers, but never another issue of the National Gazette.[59] A few years after closing down his paper, Freneau wrote to James Madison, expressing his desire to start a new publication supporting what he described as “the good old republican cause.” Freneau expected his future endeavor to capture “the Spirit of the National Gazette,” a fighting paper dedicated to liberty and localism.[60] His “‘giddy’ wandring brain,” once again, remained committed to promoting egalitarianism but conflicted on how to most effectively advance that cause.

Philip Freneau’s incessant calls for vigilance and warnings of creeping monarchy may seem, in hindsight, a bit hyperbolic. But statesmen of the 1790s did not have the benefit of hindsight. Modern Americans appreciate the republic has endured more than two centuries of relatively stable constitutional government, surviving a civil war, the threats of global fascism, and 1960s civil unrest and Vietnam War protests. Nor did eighteenth-century Americans possess the conceptual tools to rationalize that a faction could somehow remain loyal to the Constitution while critical of a sitting administration. In 1958, Historian Marshal Smelser described the 1790s as an ”Age of Passion,” a moment when even the brightest minds of the federal republic felt more than they thought about politics. Emotion rather than reason, Smelser argued, informed most political actors’ reactions.[61] Conspiracy thinking ran through both proto-parties and each side reflexively assumed the worst of their opponents. Scholar Richard Hofstadter also famously recounted this alarming trend as a consistent element of America’s paranoid politics.[62] Most recently, James Roger Sharp framed the 1790s as a series of crises that nearly destroyed the nation, correcting the popular mythology that enlightened men of reason dispassionately governed the Early Republic.[63] Alexander Hamilton, himself prone to fits of paranoia and fear-mongering, provided perhaps the most level-headed assessment of the politics of apocolypticism that colored the decade:

Tis curious to observe the anticipations of the different parties. One side appears to believe that there is a serious plot to overturn the state Governments and substitute monarchy to the present republican system. The other side firmly believes that there is a serious plot to overturn the General Government & elevate the separate power of the states upon its ruins. Both sides may be equally wrong & their mutual jealousies may be materially causes of the appearances which mutually disturb them, and sharpen them against each other.[64]

John Fenno and Philip Freneau gave a voice and an ideological framework to partisans of competing political persuasions, arming Americans with the principles with which to combat their rivals in public. However, Fenno’s paper, though favorably biased toward the Washington administration, did not start as a party paper. The nation did not yet have national parties and that editor only wished to support the new constitutional order and its principled administrations.[65] His support of the perceived monarchical policies designed by Hamilton and embraced by Washington agitated a dissenting spirit that had never quite calmed since the ratification of the federal Constitution. Freneau’s paper, then, represents the first national publication specifically designed as an opposition press. Remarkably, that paper drew support not only from likeminded Americans, but from one of Washington’s own cabinet members. And within Freneau’s pages, he fiercely advanced his objectives: normalizing public suspicion of national actors and legislation, promoting local men and their actions and warning Americans to remain vigilant against so-called monarchical designs bent on destroying the republic. In many respects, echoes of this institutionalized fourth-wall opposition still compose part of the national fabric, represented in the conservative/liberal biases reflected in The Wall Street Journal and New York Times, The National Review and The Nation, even cable networks offer a similar dichotomy; naturally the times and issues have changed, but the rowdy and at times conspiratorial nature of American political dissent continues.

[1] Gazette of the United States, May 2, 1789; see also Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 (Oxford University Press, 1993), 45-46.

[2] James Roger Sharp, The Politics of the Early Republic: A New Nation in Crisis (Yale University Press, 1993); Elkins and McKitrick, Age of Federalism.

[3] Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Beginnings of the Military Establishment in America (The Free Press: A Division of MacMillan Publishing Company, 1975); Celia Barnes, Native American Power in the United States 1783-1795 (Rosemont Publishing and Printing Corporation, 2003); Richard J. Werther, The “Western Forts” of the 1783 Treaty of Paris,” Journal of the American Revolution , January 25, 2023, allthingsliberty.com/2023/01/the-western-forts-of-the-1783-treaty-of-paris/; Michael Allen, “The Mississippi River Debate, 1785-1787,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 36, no. 4 (1977): 447-67; Kevin T. Barksdale, “The Spanish Conspiracy on the Trans-Appalachian Borderlands, 1786-1789,” Journal of Appalachian Studies 13, no. 1/2 (2007): 96-123; Gary E. Wilson, “American Hostages in Moslem Nations, 1784-1796: The Public Response,” Journal of the Early Republic 2, no. 2 (1982): 123-41; Drew McCoy, The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1980); Max M. Edling, “‘So Immense a Power in the Affairs of War’: Alexander Hamilton and the Restoration of Public Credit,” William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2007): 287-326.

[4] Jack N. Rakove, “The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George Washington,” in eds., Richard Beeman and Edward C. Carter II, Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity (University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 261-94.

[5] Shawn David McGhee, “‘What Magic There is in Some Words!’: John Fenno’s Public Crusade for an American National Identity,” Journal of the American Revolution, January 30, 2025, allthingsliberty.com/2025/01/what-magic-there-is-in-some-words-john-fennos-private-crusade-for-an-american-national-identity/; Shawn David McGhee, “‘One Great People’: John Fenno’s Private Crusade for an American National Identity,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 1, 2025, allthingsliberty.com/2025/04/one-great-people-john-fennos-public-crusade-for-an-american-national-identity/; Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2009), 19-61.

[6] John Fenno to Joseph Ward, January 31, 1789, in John B. Hench, ed., “Letters of John Fenno and John Fenno Ward, 1779-1800, Part 1: 1779-1790,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 89, no. 2 (1979), 1:356.

[7] Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, May 9, 1791, in eds., Julian P. Boyd, et al., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 45 vols. (Princeton University Press, 1950-2021), 14:20.

[8] McGhee, “One Great People”; Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 19-61.

[9] Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, May 15, 1791 in Boyd., et al., Papers of Jefferson, 20:414-16.

[10] Lewis Leary, That Rascal Freneau: A Study in Literary Failure (Rutgers University Press, 1941), ix.

[11] Jacob Axelrad, Philip Freneau: Champion of Democracy (University of Texas Press, 1967), 3-8.

[12] Leary, That Rascal Freneau, 14-17.

[13] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 37-38; Leary, That Rascal Freneau, 34-36.

[14] John M. Murrin, “Princeton and the American Revolution,” Princeton University Library Chronicle 38, no. 1 (1976): 1-10; Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 31, 37-39.

[15] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 40-41.

[16] Philip Freneau to Madison, November 22, 1772, in eds., William T. Hutchinson et al., The Papers of James Madison, 17 vols. (University of Chicago Press, 1962-1991), 1:77-70; For the poem, see Fred Lewis Pattee, ed., The Poems of Philip Freneau: Poet of the American Revolution, 3 vols. (University Library, 1902-1907), 3:396-99.

[17] Freneau to Madison, November 22, 1772, in Hutchinson et al., Papers of Madison, 1:77-70.

[18] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 51-53.

[19] Philip Freneau, “Libera, Nos, Domine,” in Pattee, Poems of Freneau, 1: 140.

[20] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 57; See also William L. Andrews, “Freneau’s ‘A Political Litany’: A Note on Interpretation,” Early American Literature 12, no. 2 (1977): 193-96.

[21] For an outstanding analysis of Freneau’s patriotic propaganda, see Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 62-65.

[22] Ibid., 76-77.

[23] For a valuable treatment of Freneau and his art in St. Croix, see Jane Donahue Eberwain, Early American Literature 12, no. 3 (1977-78): 271-76.

[24] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 87-89.

[25] Ibid., 94.

[26] For a useful analysis of Freneau’ poem, “The British Prison Ship,” see Edwin G. Burrow, Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners during the Revolutionary War (Basic Books, 2008), 170-75.

[27] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 183.

[28] Leary, That Rascal Freneau, 192.

[29] Jefferson to Madison, July 21, 1791, in Boyd, et al, Papers of Jefferson, 20:657-58.

[30] Madison to Edmund Randolph, September 13, 1792, in Hutchinson, et al., Papers of Madison, 14:364-66.

[31] Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, May 15, 1791, in Boyd, et al, Papers of Jefferson, 20:414-16.

[32] See Madison to Charles Simms, August [23?], 1791, in Hutchinson et al, Papers of Madison, 14:73; See also Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, November 13, 1791, in Boyd., et al., Papers of Jefferson, 22:294.

[33] Jefferson to Freneau, February 17, 1791, in Boyd., et al., Papers of Jefferson, 19:351.

[34] Freneau to Jefferson, March 5, 1791, in ibid., 19:416-17.

[35] John Fenno’s Philadelphia office at the start this rivalry was 69 High Street, between Second and Third Streets. See masthead of the Gazette of the United States, November 2, 1791; Philip Freneau’s office was 239 High Street and Sixth Street. See masthead of the National Gazette, November 3, 1791. Both printers moved their offices, but remained in the general vicinity of each other.

[36] Jefferson to David Humphreys, August 23, 1791, in Boyd., et al., Papers of Jefferson, 22: 61-62.

[37] Jeffrey Pasley, The Tyranny of Printers: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 60-66.

[38] Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, May 15, 1791, in Boyd, et al, Papers of Jefferson, 20:414-16.

[39] Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, November 13, 1791 in ibid., 22:294.

[40] Pasley, Tyranny of Printers, 60-66.

[41] “Cauis,” National Gazette, January 16, 1792.

[42] “Farmer,” National Gazette, March 15, 1792.

[43] “Brutus” ibid.

[44] “Brutus” iNational Gazette, March 22, 1792.

[45]“Thoughts on the Excise Law, so far as it Respects the Western Country,” National Gazette, February 9, 1792.

[46] National Gazette, April 5, 1792.

[47] “The Spectator,” National Gazette, March 8, 1792.

[48] National Gazette, December 19, 1791.

[49] “A Friend of the Union,” Gazette of the United States, February 17, 1790.

[50] National Gazette, January 9, 1792.

[51] “Aratus,” National Gazette, November 24, 1790.

[52] “A Gentleman from Charleston,” ibid.

[53] National Gazette, November 24, 1791, January 16, 1792, February 2, 1792.

[54] “Caius,” National Gazette, February 6, 1792.

[55] “Sentiments of a Republican,” National Gazette, April 26, 1792.

[56] Notes on Cabinet Meeting on Edmund Charles Genet, August 2, 1793, in Boyd., et al., Papers of Jefferson, 26:601-603.

[57] National Gazette, October 27, 1793.

[58] Jefferson to Madison, August 25, 1793, in Boyd, et al, Papers of Jefferson, 26:756; Sharp, Politics of the Early Republic.

[59] Axelrad, Philip Freneau, 266.

[60] Freneau to Madison, December 1, 1796, in Hutchinson, et al., Papers of Madison, 16:419-20.

[61] Marshall Smelser, “The Federalist Period as an Age of Passion,” American Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1958): 391-419.

[62] Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style of American Politics and Other Essays (Alfred A. Knopf, 1965).

[63] Sharp, Politics of the Early Republic.

[64] Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, Enclosure [Objections and Answers Respecting the Administration], August 18, 1792 in ed., Harold C. Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 27 vols. (Columbia University Press, 1967-1987), 12:229-58.

[65] McGhee, “One Great People.”

One thought on ““The Good Old Republican Cause”: Philip Freneau’s Principled Stand against the Shadow of Monarchy”

I have heard it said several times that Hamilton favored a monarchy and that Washington concurred. This has been used to condemn both men albeit Washington to a (much) lesser extent. But I do not accept this conclusion. Yes, Hamilton feared a “tyranny of the States” more than a limited monarchy, but that is not the same as preferring a king. As for Washington, his entire life was directed at a republic WITHOUT a king. Had he wanted a king, HE could have been that king. Obviously such was not the case.

Hamilton saw that the biggest threat to the republic was bad finances ~ and he was right. We look upon his National Bank in light of what came after, not before or during that time in history! The US almost lost the revolution because of bad finances. It is a shame that the book almost completed by Charles Thompson, the Secretary of the Congress throughout the war was never put into print. According to Nathaniel Philbrick, author of the book Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution: “(T)he real Revolution was so troubling and strange that once the struggle was over, a generation did its best to remove all traces of the truth. No one wanted to remember how after boldly declaring their independence they had so quickly lost their way; how patriotic zeal had lapsed into cynicism and self interest . . .”Thomson, a man described by one historian as “. . . the Prime Minister” of Congress had decided after the war to write a history of the Continental Congress for though delegates came and went over the years, he had remained a part of that body. His friend John Jay told him, “. . .no person in the world is so perfectly acquainted with the rise, conduct, and conclusion of the American Revolution as yourself.” However, the matter did not go as originally planned. Soon after his retirement in July 1789, Thomson set to work on a memoir of his tenure as secretary to the Congress, eventually completing a manuscript of more than a thousand pages. But as time went on and the story of the Revolution became enshrined in myth, Thomson realized that the account, entitled ‘Notes of the Intrigues and Severe Altercations or Quarrels in the Congress,’ would contradict all the histories of the great events of the Revolution. As a result, around 1816 he decided that it was not for him ‘to tear away the veil that hides our weaknesses,’ and he destroyed the manuscript. ‘Let the world admire the supposed wisdom and valor of our great men,’ he wrote, ‘Perhaps they may adopt the qualities that have been ascribed to them, and thus, good may be done. I shall not undeceive future generations.’”

One wonders how much of the criticism of men like Washington and Hamilton would have survived the facts concerning the actions of the Congress during the war ~ and after. Very little is every achieved by duplicity even when practiced with the best of intentions.