River crossings during the American Revolution were common events. Historians, patriotic organizations and living history enthusiasts focus on several of these crossings with commemorations and reenactments. The most celebrated of all crossings is Washington’s Crossing of the Delaware on December 25, 1776. State parks, in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, recognize the crossing and events of late 1776 and early 1777 that helped to change the course of the Revolution. Lord Charles Cornwallis’s crossing of the Catawba River, in North Carolina, at Cowans Ford on February 1, 1781, initiated Nathanael Greene’s race to the Dan River in Virginia. Greene’s crossing of the Dan took place on February 15 of that year. Both Cornwallis’s and Greene’s crossings are commemorated annually although Cowan’s Ford now lies inside the secure area of the McGuire Nuclear Power Station and is not readily accessible. Another river crossing in Virginia that is celebrated annually is Anthony Wayne’s crossing of the Potomac on May 31, 1781, in route to reinforce Lafayette in countering the maneuvers of Lord Cornwallis. Of the crossings above, only Cornwallis’s crossing of the Catawba was opposed by enemy forces. Each of these crossings were part of a larger campaign.

An opposed crossing in Virginia of the lower James River by Patriot forces under command of Col. William Woodford, in November of 1775, is relegated to a footnote in the Revolution. This crossing was one of the first operations in a series of linked events that evolved into the campaign to remove royal colonial governance from the Colony and later State of Virginia. Just as Washington’s crossing of the Delaware changed the course of the Revolution in the middle colonies, Woodford’s crossing of the James River in November 1775 changed the course of the Revolution in Virginia.[1] Opposed river crossings are dangerous and risky operations, particularly for new untrained or inexperienced units, and Woodford’s force, unlike Cornwallis’s at Cowans Ford, suffered no losses in this crossing. One of the important elements in the success experienced during this crossing was the effective employment of rifles by skilled Patriot riflemen.

The Rifle vs. the Musket

The first ten companies authorized as part of the new Continental Army by the Second Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, later increased to thirteen companies, were designated as rifle companies.[2] The decision to specifically authorize rifle companies was to provide the New England units forming around Boston, often referred to as the as the “Army of Observation” and armed primarily with short range, smooth bore weapons, with accurate long range infantry firepower, increasing the standoff distance because Patriot forces lacked artillery.[3] Rifles were plentiful in the backcountry of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia and these original rifle companies were formed in the western and norther counties of the colonies where strong Patriot sentiments dominated. Virginia’s initial contribution was two rifle companies commanded by Daneil Morgan from Frederick County and Hugh Stephenson from Berkeley County. These two companies along with Maryland’s two companies and Pennsylvania’s nine provided a national character to the new Continental Army. All thirteen companies went into action around Boston by mid-August 1775.[4]

By 1775, the rifles in use in the North American backcountry had developed into a distinctly different weapon than the smooth bore musket.[5] Rifles and the riflemen who employed them had great value early in the Revolution. Accuracy and range were the great advantages to employing rifles over muskets. Lacking cannons early in the Revolution, rifles were a substitute for providing long range fires to increase standoff distances. Many residents of the borderlands or frontier regions of the middle and southern colonies owned their own rifles and used them regularly. In Virginia minutemen who brought their own rifles received additional monetary compensation for their service. Designating units as rifle vs. musket incentivized the use of rifles and helped solve the challenges associated with equipping thousands of men with publicly sourced weapons that were in short supply – it was quicker and simpler to pay a man to bring his own weapon.[6]

Dr. James Thatcher recorded the exploits of these original riflemen employed around Boston in his diary.

Several companies of riflemen, amounting, it is said, to more than fourteen hundred men, have arrived here from Pennsylvania and Maryland; a distance of from five hundred to seven hundred miles. They are remarkably stout and hardy men; many of them exceeding six feet in height. They are dressed in white frocks, or rifle-shirts, and round hats. These men are remarkable for the accuracy of their aim; striking a mark with great certainty at two hundred yards distance. At a review, a company of them, while on a quick advance, fired their balls into objects of seven inches diameter, at the distance of two hundred and fifty yards. They are now stationed on our lines, and their shot have frequently proved fatal to British officers and soldiers who expose themselves to view, even at more than double the distance of common musket-shot.[7]

Surviving diaries of the original Continental Army musket and riflemen serving around Boston record the effectiveness of riflemen in engaging targets at long range in attempts to increase standoff distances and counter British artillery.[8]

The James River

The James River begins in the Appalachian Mountains of Western Virginia and flows 444 miles before emptying into the Chesapeake Bay. The James is Virginia’s largest river, with a 10,000 square mile watershed. The lower James River is a brackish tidal estuary that flows first into Hampton Roads before entering the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The lower James is the home of Jamestown, the first permanent English Colony in America. The James is over two miles wide near Jamestown with a normal two-to-three-foot tidal range. It is a formidable body of water.

For the last 100 years the Virginia Department of Transportation has operated a ferry crossing for transporting cars, trucks and pedestrians from James City County on the north bank to Surry County on the south bank of the James. The crossing, over two miles in length, uses several modern diesel-powered ferries and takes twenty minutes. This crossing is located near where some of the first military engagements took place in Revolutionary Virginia and where Patriots first crossed the James in November 1775.[9]

Enemy and Friendly Situation in the fall of 1775

Virginia’s royal colonial governor, John Murray, known as Lord Dunmore, established his seat of government afloat after being driven from the colonial capital in Williamsburg. By late October, Dunmore garrisoned his 175 British regulars of the 14th Regiment of Foot at the Gosport shipyard, across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk; the shipyard was owned by Loyalist and Scotsman Andrew Sproul. Dunmore, with support from several British warships and armed Loyalist vessels, raided for supplies throughout Tidewater Virginia and seized merchant ships entering the Chesapeake Bay, denying the Patriots critical supplies and solving some of his own supply challenges. He very effectively employed his regular soldiers, marines, sailors and Loyalist volunteers in raiding and limited offensive operations to break up Patriot formations and keep his opponents south of the James from fully organizing politically and militarily against the crown.[10]

Dunmore made up for his small numbers of land forces by arming several shallow-daft vessels that operated as an extension of the British Navy warships assigned to support him. He embarked raiding parties aboard these vessels, patrolled the local waters and landed forces at key locations to prevent Patriots from moving freely on the numerous navigable waterways in Tidewater Virginia. Several Royal Navy vessels rotated through Virginia waters during the summer and fall of 1775. At the time of the Patriot crossing of the James River in November, two Swan class sloops-of-war, the Kingfisher and the Otter, supported Dunmore and his naval and land forces. Dunmore’s intelligence was good; he was able to receive timely reports on the movement and numbers of Patriot forces. This allowed him to posture his limited land and naval forces to best counter Patriot movements.[11]

The Patriot government operating first from Richmond and later Williamsburg ordered the mobilization of over 9,000 men with legislation approved during August 1775. By late October, 1,000 men assembled at College Camp, located on the campus of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, with additional men at Hampton.[12] The challenge came in arming, equipping and supplying this number of men to build offensive military capacity. As these actions were underway, the Patriot Committee of Safety, on October 24, ordered Colonel Woodford with his 2nd Virginia Regiment to cross the James River and liberate Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties from royal colonial rule and defeat the forces of Lord Dunmore.[13]

While the Patriots were able to build a land force or army rather quickly, building a navy with any capacity took considerably longer. As a result, Dunmore and his limited number of land and naval forces effectively controlled the waterways of Tidewater Virginia during the fall of 1775. This included the lower James River, the river Woodford needed to cross to reach and engage Dunmore and his forces operating primarily in two coastal counties, Norfolk and Princess Anne. Because of the mercantile interests associated with the Borough of Norfolk, many residents were Loyalists, making the largest city in Virginia key to military control of the region and future state. Ejecting or at a minimum neutralizing Dunmore and his military capabilities to better protect the Patriot citizens and suppress Loyalist sentiment and support became a priority for Virginia’s Patriot government.[14]

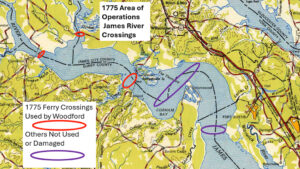

On October 26-27, 1775, Lt. Matthew Squire commanding the sloop-of-war Otter attempted to force entry into the Hampton River to destroy the town of Hampton as punishment for Patriot actions. This attempt failed, repulsed by Woodford with some of the same forces he needed to cross the James and attack Dunmore. This action delayed the crossing of the James and allowed for repositioning of the two British sloops-of-war to oppose the Patriots efforts to cross. Repulsed at Hampton, Captain Squire moved the Otter and her supporting shallow-draft tenders up the James River and on November 1 shelled the Jamestown Ferry House and attempted to damage the James River ferries docked on Jamestown Island, but damage was minimal.[15]

Long Range Rifle Fire

Edmund Pendelton, the President of Virginia’s Committee of Safety, reported to the Second Continental Congress during mid-October 1775 that, “Lord Dunmore, it is said, is very much afraid of the riflemen, and has all his vessels calked up on the sides. Above a man’s height, however, they may perhaps pay him a visit, ere long.”[16] The main factor in this first successful defense of the ferries was the rifle and the riflemen who professionally employed the weapon. Lacking cannons, sufficient gunpowder and shot, the Patriots effectively employed rifles in the hands of experienced riflemen to defend key locations along Virginia’s shoreline. While land-based forces could not protect every potential landing site or ferry crossing they did man and protect key infrastructure needed to cross the James River, near Williamsburg.

The first well-documented use of rifles in defending against well-armed landing parties occurred at Hampton on October 26-27. Colonel Woodford’s arrival with a volunteer company of Culpeper District riflemen, led by Capt. Abraham Buford, on the morning of October 27 stopped the attack on Hampton and resulted in the first reported British and Loyalist casualties in Virginia.[17] Dunmore’s landing parties operated from tenders and barges equipped the three- and four-pound cannons and smaller swivel guns. Effective against shore targets from ranges beyond 300 yards, riflemen targeted the exposed gunners and crew members manning these shallow-draft landing vessels. While there are few reported kills, the well-aimed long range rifle fire was effective in interrupting their loading and firing processes, rendering them only marginally effective and keeping them 300 to 400 yards from the shoreline.[18] “It is incredible how much they dread a Rifle,” wrote John Page to Thomas Jefferson.[19]

Dunmore’s intelligence efforts and the lack of effective operational security by the Patriots revealed the plans to cross the James. The arrival of companies in Williamsburg was regularly reported in the Virginia Gazette. Loyalists south of the James River feared the arrival of Patriot forces and reported events to their associates and family in Great Britain. Rumors that the Patriots planned to occupy destroy the Borough of Norfolk circulated widely.[20] After the Otter returned to Norfolk Harbor in early November, Dunmore ordered the sloop-of-war Kingfisher accompanied by multiple tenders and lading barges up the James River to interdict and stop the crossing of Patriot forces to the south side of the river.

The Crossing

Patriot forces numbering about 250 men, or four companies, about thirty-five percent of Woodford’s assigned forces, probably under the command of Lt. Col. Charles Scott of the 2nd Virginia Regiment, crossed, likely on the evening or morning hours of November 8-9, under the cover of darkness. This initial detachment included a mix of both musket and riflemen. Woodford’s task-organized regiment consisted of eleven companies, six of his 2nd Virginia companies and five from the Culpeper Minute Battalion. About 40 percent of Woodford’s men were from units designated as rifle companies.[21] This initial crossing probably took place before the Kingfisher and her tenders arrived to interdict it.

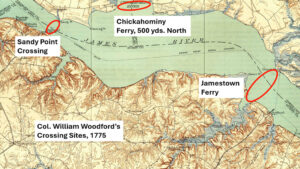

On November 9, at about 1:00 pm, the sloop-of-war Kingfisher under the command of Lt. James Montagu, and three tenders arrived off Burwell’s Ferry, just downstream from Jamestown Island, and attempted to board a small vessel lying about 300 yards from the shore. The boarding party from the Kingfisher made two attempts to board the smaller vessel, both repulsed by a ten-man rifle guard stationed there to protect the ferry. These riflemen were members of Capt. John Green’s Culpeper District rifle company assigned to Col. Patrick Henry’s 1st Virginia Regiment, likely under the command of Ens. John Lee.[22] About three hours later the Kingfisher began heavy cannonading, and one six-pound shot went through the house at the waterside and hit the ferry house occupied by a large family. However, no one was hurt. About three hours later Kingfisher again fired three or four broadsides and remained near the ferry but did not attempt another landing or venture near the shore.[23] That evening the Kingfisher and tenders moved downstream to Mulberry Island, the site of another crossing point, today part of Fort Eustis, an active US Army installation, and destroyed some boats on both sides of the river that were not under guard.[24]

The Kingfisher returned to the waters off Jamestown Island on November 13 but made no attempt to land troops. Two days later, on the evening of November 15, the Kingfisher attempted to land a party on a beach about one-half mile east of Jamestown Island, today Archers Hope near the Colonial Parkway. Two of Captain Green’s men were patrolling the beach; one remained in place while the second went for reinforcements. The man on the beach continued to fire until he heard a loud scream after which the landing party turned away and returned to the Kingfisher. The Kingfisher and tenders returned to Jamestown Island on November 16, put a six-pound ball through the kitchen chimney of Colonel Travis’s house and fired on a Patriot courier boat crossing the river above their anchorage, but did no other damage. Four additional companies, another 250 men with supplies, crossed between November 9 and 18; the Kingfisher and tenders failed to stop them.[25]

The Kingfisher’s operations in the river did delay the crossing of the remainder of Colonel Woodford’s force. To counter the Kingfisher and her tenders, Patriots simply moved the crossing upstream to Sandy Point in Charles City County. This added ten to twelve miles and an additional ferry crossing near the confluence of the Chickahominy River with the James River, where Virginia Highway 5 crosses today. The James River is much narrower at Sandy Point, allowing the riflemen on each bank to provide sufficient standoff. Woodford and his last three companies, about 200 men, crossed on the evening of November 18-19. It took ten days to move over 700 men and their equipment to the south side of the river but with no loss of personnel or critical equipment.[26]

The Kingfisher and her tenders remained near Jamestown for one more day, returning to Norfolk on November 20. Before they returned, Capt. John Green’s riflemen captured an oyster boat attempting to deliver fresh oysters to the Kingfisher; Green’s men dined on oysters that evening. Now safely on the south side of the James River, Colonel Woodford on November 22 ordered 215 privates, 103 of them riflemen, with NCOs and officers, five companies, to march to Great Bridge with only weapons and blankets, to test the enemy’s defenses. The men were led by Lt. Col. Charles Scott of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and Maj. Thomas Marshall of the Culpeper Minute Battalion. Scott’s detachment arrived on November 28 followed by Colonel Woodford and the main body on December 2. One week later, on December 9, in the Battle of Great Bridge, Woodford’s musket men and riflemen bloodied Dunmore’s regulars and Loyalist militia.

Conclusion

The successful crossing of the James River by Patriot forces between November 9 and 19, 1775, initiated a series of events that led to Lord Dunmore’s eventual departure from Virginia in early August 1776.[27] Virginia was now free to send men and resources to support General Washington’s army. Had this crossing failed or even been significantly delayed, the history of the Revolution would have been much different. Virginia’s political leadership led the movement at the Second Continental Congress for independence, with Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introducing the resolution for independence on July 2, 1776. With Virginia, the Revolution had life.[28] Virginia’s success in removing royal colonial governance form the colony started with the successful crossing of the James River in November 1775, an operation conducted under enemy pressure and where the riflemen proved their value.

[1] The Virginia campaign of 1775-76 to remove royal colonial authority and governance from the colony and later state began with the Gunpowder Incident in April 1776 in Williamsburg and ended with the Battle of Cricket Hill-Gwynn’s Island in July 1776 when Lord Dunmore departed Virginia, never to return. This campaign lasted fifteen months.

[2] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905), 2:89-90, 173, 223.

[3] Robert K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, 1983), 4-44. The Army of Observation would evolve into the Continental Army over the summer of 1775.

[4] Patrick H. Hannum, “Americas First Company Commanders,” Infantry, 102, no. 4 (October-December 2013), 12-19.

[5] John W. Wright, “The Rifle in the American Revolution,” The American Historical Review, 29 (1924): 293-299.

[6] Third Virginia Convention, The Proceedings of the Convention of Delegates, Ordinances, August 1775, 33, www.google.com/books/edition/_/bQEtAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22Ordinance%20for%20raising%20and%22; Patrick H. Hannum, “Virginia’s 1775 Regular Company-Level Military Force Structure,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 15, 2022, allthingsliberty.com/2022/09/virginias-1775-regular-company-level-military-force-structure/.

[7] Dr. James Thacher, Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War from 1776 to 1783, www.americanrevolution.org/thacher.html. Also see Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), September 9, 1775, for another account of the accuracy of rifle fire by the Maryland riflemen around Boston.

[8] Kenneth Roberts, March to Quebec, Journals of Members of Arnold’s Expedition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1946), 409, 476, 471, 508-9.

[9] Virginia Department of Transportation, Ferries, Jamestown-Scotland Ferry, www.vdot.virginia.gov/about/our-system/ferries/.

[10] Dunmore’s most successful operation occurred on November 15, 1775, at Kemp’s Landing, where he neutralized the Princess Anne District Minute Battalion forming there, allowing him to issue his Proclamation declaring martial law and limited emancipation of indentured servants and enslaved of the rebels. Patrick H. Hannum, “Recognizing the Skirmish at Kemp’s Landing,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 17, 2018, allthingsliberty.com/2018/12/recognizing-the-skirmish-at-kemps-landing/; Patrick H. Hannum, “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation: Information and Slavery,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 30, 2019, allthingsliberty.com/2019/12/lord-dunmores-proclamation-information-and-slavery/.

[11] The Otter arrived in Virginia in early June 1775 and operated in support of Dunmore through his departure from Virginia in early August 1776. The Kingfisher arrived in Virginia in early September 1775 and operated in support of Dunmore through early March 1776, when ordered to Boston. Each vessel had a crew of 100 men. NDAR, 1:428; 2:343 & 428; 4:245; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), September 29, 1775; (Dixon & Hunter) October 14, 1775; Samuel Leslie to William Howe, November 1 (postscript November 260, 1775, Peter Force, ed., American Archives (AA), Ser. 4, 3:1717, archive.org/details/AmericanArchives-FourthSeriesVolume3peterForce/page/n857/mode/2up.

[12] Samuel Leslie to William Howe, November 1, 1775, AA, 4:3: 1717-17.

[13] Third Virginia Convention, Ordinances, 29-37, Scribner & Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia (Charlottsville: University of Virginia Press, 1978), 4:270-71.

[14] Revolutionary Virginia, 4:14.

[15] Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), November 2, 1775; Page to Jefferson, NDAR, 2:190-92.

[16] Edmund Pendleton to Richard Henry Lee, October 15, 1775, in David John Mays, ed., The Letters and Papers of Edmund Pendleton, 1734-1803 (Charlotteville: University of Virginia Press, 1967), 1:121-23.

[17] Virginia Gazette (Pinkney) October 26, 1775, November 2, 1775.

[18] Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), November 2, 1775; Page to Jefferson, NDAR, 2:190-92.

[19] John Page to Thomas Jefferson, November 11, 1775, in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (NDAR) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966), 1:991.

[20] John Johnson to ? November 16, 1775, Revolutionary Virginia, 4:414-17.

[21] Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), November 9, 1775; Virginia Gazette (Purdie) November 11, 1775, Third Virginia Convention, Ordinances, 29-37; Hannum, “Virginia’s 1775 Regular Company-Level Military Force Structure.” Not all the units designated as rifle or musket companies of battalion were equipped exclusively with the designated weapons, but the preponderance of weapons would have been the primary weapon designated. See, multiple documents in Revolutionary Virginia, volumes 4-7.

[22] Pension Application John Lee, VAS871, revwarapps.org/VAS871.pdf, Lee continued his service in the 2nd Virginia State Regiment as a captain and major through October 1781.

[23] Page to Jefferson, NDAR, 2:190-92; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 10, 1775.

[24] Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 17, 1775.

[25] Pendleton to Lee, November 27, 1775, 1:121-3.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Patrick H. Hannum, “Cricket Hill and Gwynn’s Island: Captain Arundel’s Only Fight,” Journal of the American Revolution, February 26, 2025, allthingsliberty.com/2025/02/cricket-hill-and-gwynns-island-captain-arundels-only-fight/.

[28] Journals of the Continental Congress, V, 507 & 510-18. For example, four months after Dunmore was ejected from Virginia, 20 percent of the troops that crossed the Delaware River with Washington were from Virginia. All these units were directly involved in ejecting Dunmore during the summer of 1776. Had Dunmore remained a threat to Virginia this would not have been possible. With Virginia and her resources, the Revolutionary movement had a chance of success. This successful campaign to remove Dunmore relied on the riflemen for long-range fire until the summer of 1776 when Virginia’s forces, in the final engagement of the campaign, effectively employed cannons during the fight at Gwynn’s Island, 9-10 July 1776.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...