The Culper Spy Ring. An espionage network composed primarily of civilians funneling military intelligence to Gen. George Washington out of British-occupied New York City and Long Island. Washington once referred to it as “the channel upon which I most depend.”[1] It has been the subject of several books and a television show, so many would suspect there is little new information left to uncover.

With a Revolutionary War story so intertwined with local lore, mistakes are nonetheless still routinely found in the Culper Spy Ring’s history. Quite often when those errors arise though, they can be traced back to Morton Pennypacker, an early twentieth century Long Island historian famous for bungling his facts. He was the one who first attached a historical narrative to the ring. Yet, he is not to blame for the confusion over the occupation of Austin Roe, the primary cross-island courier for the Culper Spy Ring who resided in Setauket. This is one circumstance in which Pennypacker remains blameless.

The Myth of Austin Roe the Tavernkeeper

For decades, it has been held that Austin Roe worked as a tavernkeeper, operating a tavern from his home in Setauket. This supposed fact made its earliest appearance in a privately published book from 1904 entitled The Diary of Captain Daniel Roe. The author, Alfred Seelye Roe, a descendant of both Austin Roe and his brother Daniel Roe due to some kissing cousins, wrote, “Of Austin . . . it should be stated that . . . during the earlier part of his life, he kept a tavern in Setauket, where his unmarried brother, Justus, made his home with him. Later he moved to the south shore.”[2]

Since the release of that book, Austin’s occupation as tavernkeeper has been reintroduced in virtually every publication on the Culper Spy Ring to varying degrees and often plays a part in how the ring functioned. Brian Kilmeade’s George Washington’s Secret Six, for example, claimed Austin’s occupation provided him a cover, allowing him to travel into the city on “the pretense of purchasing provisions for his business.”[3]

That said, it was quite easy to believe Austin Roe owned a tavern since Washington did famously stay in Austin’s home during his 1790 tour of Long Island and a tavern would certainly make for suitable accommodations. Unfortunately, the diary Washington kept during his travels says only a single line regarding his visit to the home of Austin Roe on April 22, as the president was significantly more interested in local soil quality. Washington wrote, “thence to Seta[uket] 7 [miles] more to the House of a Capt[ain] Roe which is tolerably dec[ent] with obliging people in it.”[4]

Referring to Austin Roe by his military title as a captain in the Suffolk County militia, Washington notably did not describe Austin’s home as a tavern.[5] Washington’s statement would be less significant if Washington was not explicitly clear about the type of establishments he was staying in during his tour. The same day Washington mentioned lodging at the Roe home, he specifically identified the stop prior as a tavern—Hart’s Tavern, formerly in Patchogue.[6]

The day before, Washington also mentioned two private homes that were formerly business establishments. These two residences were no longer licensed as taverns but now occasionally offered lodgings to travelers for a price—perhaps what might be considered closer to an inn or bed and breakfast. Washington made sure to characterize both. He said of the location in South Hempstead that his party baited their horses “at the House of one Simmonds, formerly a Tavern, now of private entertainment for Money.”[7] Later that same day, Washington “dined at one Ketchums w[hich] had also been a public House but now a private one receiv[ing] pay for what it furnished.”[8]

Washington was also clear to denote when he was staying in private homes, but providing payment as though they were public establishments. He wrote of Islip’s Sagtikos Manor, “After dinner we proceeded to a Squire Thompsons such a House as the last, that is, one that is not public but will receive pay for everything it furnishes in the same manner as if it was.”[9]

Trusting that Washington was capable of discerning the nature of his own lodgings, there is no indication that Austin Roe owned a tavern or that his house, prior to that time, ever served as one. So how did the myth of Austin Roe’s tavern in Setauket come about?

The earliest reference to a “Roe’s Tavern” so far discovered comes from the diary of Dr. Samuel Thompson. Samuel Thompson was a local physician and Patriot who served on the Brookhaven Committee of Safety prior to Long Island’s occupation with several others who would become members of the Culper Spy Ring. He mentioned the tavern in his diary entry for April 29, 1800, but failed to specify the tavern’s location. A Roe Tavern assuredly did exist, only on the opposite side of the island in Patchogue. Various nineteenth century newspaper articles conflict on the exact opening year, but most generally believe the tavern in Patchogue was started at least by 1807 and begun by Austin Roe’s son, Justus Roe (not to be confused with Austin’s brother of the same name).[10]

Could Patchogue’s Roe Tavern have been open in 1800? Could the Roe home in Setauket have become a tavern closer to 1800? In a 1903 publication mentioning the subject—just a year before the release of The Diary of Captain Daniel Roe—historian Peter Ross states there was a short-lived Roe Tavern in Setauket run by various Roe family members, but never by Austin himself. That said, like most historians of the period, Ross also failed to indicate any sources.[11] As no primary sources substantiate his claims, even these statements should be considered with some healthy skepticism.

Regardless of whether a tavern run by a Roe relative existed in Setauket in 1800, Austin Roe would not have been involved as, by that time, he had already moved to a farm on Pine Neck in what is now East Patchogue.[12] A small remaining parcel of that farm still exists to this day. Given his location and with no evidence to the contrary, Austin Roe does not appear to have been involved in operating the Roe Tavern in Patchogue either, which was situated a few miles west of his home.

So if not a tavern or innkeeper, what was Austin Roe’s true calling?

Austin Roe the Joiner

Austin Roe was a joiner—a type of woodworker. He even swore to it under oath. He served as one of three witnesses to a will made in 1779 and, when the will was to be proved in 1794, the judge included Austin’s occupation in a typical manner for wills of the era, particularly when multiple individuals might have the same name. Even though this attestation came after the war, a variety of additional sources show that this was always Roe’s primary occupation.[13]

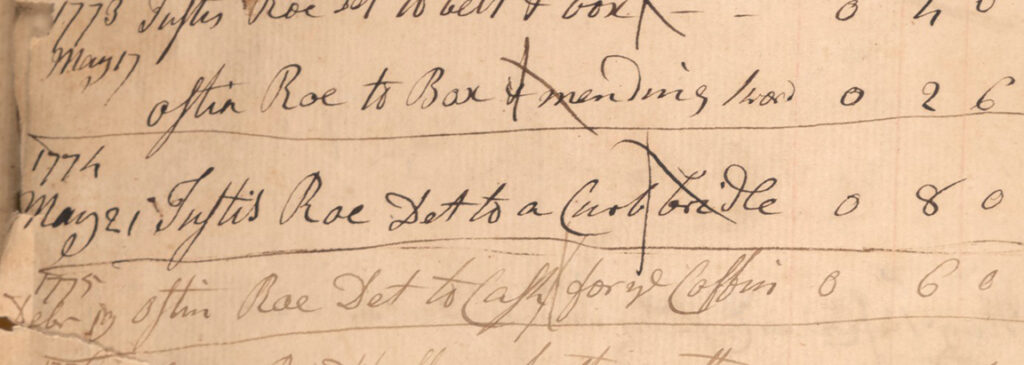

A joiner in the revolutionary era was “one whose trade is to make utensils of wood joined together” and Roe clearly was capable of producing an assortment of items.[14] From surviving account books where he is mentioned, multiple entries demonstrate his craftmanship.

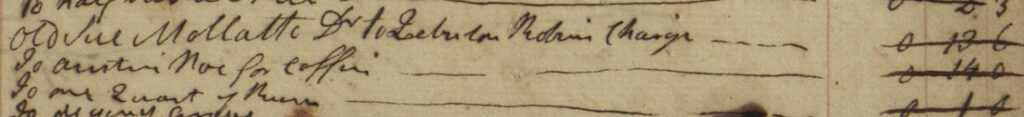

In most entries, Austin Roe was making windows—from crafting the frames and sashes, to puttying them in preparation for glazing the panes.[15] In addition, he could be seen producing and mending furniture, such as desks, chairs, and tables.[16] Sadly, responsibility fell to him to build coffins for members of the community.[17]

Roe clearly took on bigger projects as well. Less than a month after Washington’s visit in 1790, he completed building a house.[18] Not only does this point to a wider skillset with woodworking, but it also counters a family legend that he supposedly broke his leg in a rush to receive Washington, causing him to be permanently lame.[19] He also often took on the responsibility of procuring the raw material for his projects, cutting his own timber when necessary.[20]

In addition to his woodworking profession, Roe presumably kept a farm, as was the norm among others in his community. In fact, when the British took oaths of allegiance in 1778 from Austin Roe’s native township of Brookhaven, they failed to record most people’s primary occupations. They listed nearly everyone as a farmer who managed some semblance of a farm in the area, even well-known doctors and judges. Roe too was only listed as a farmer.[21]

Though records are scarce regarding Roe’s farm in Setauket, there are accounts related to him raising cattle for both beef and milk, and possibly sheep for wool. It is unclear how much land he had to dedicate to livestock as he frequently bought the fodder to feed the animals or paid to let them graze among his neighbor’s herds.[22]

Austin Roe the Joiner Becomes Austin Roe the Carter

Not surprisingly, when war came to Long Island, Roe found his life in upheaval. While records evince him plying his trade immediately before and after the Revolution, his joinery practice appears to have come to a screeching halt when Long Island succumbed to British occupation in the summer of 1776. The change could just be a result of an incomplete record, but more likely it was because there was less demand for wood products generally and due to the scarcity of raw material.

Throughout the occupation, wood was a commodity in high demand. British and Loyalist armed forces encamped on Long Island and in nearby New York City sought Long Island’s forests as the main source for their fuel. Thus, the price for the resource was high.

Soldiers had a tendency to help themselves to whatever they could reasonably take from Long Island’s residents. Trees were cut either without permission, or with promises to repay that would never be satisfied. Fences and wooden buildings might be stripped and stolen.[23] Additionally, with the impressment or confiscation of other necessaries like livestock or crops by the British, as well as robberies committed by Patriot privateers from the mainland, many in Austin Roe’s locality found themselves under financial dire straits throughout the war.[24]

It is for this reason—and also perhaps as part of a cover for his role in the Culper Spy Ring’s espionage operation—that Austin Roe spent more time carting. According to the entries in an account book believed to have belonged to spy ring member Abraham Woodhull, an entry on June 25, 1780—a time reflecting the height of the spy ring’s activities—Roe carted locally produced goods, such as butter, into New York City.[25] There he exchanged them for finer, imported goods, like wine, sugar and nutmeg.[26] He also carried out exotic fabrics, like a yard of denim, which at that time was a coarse cotton fabric so named because it was originally woven in Nimes, France (hence “de Nimes”).[27]

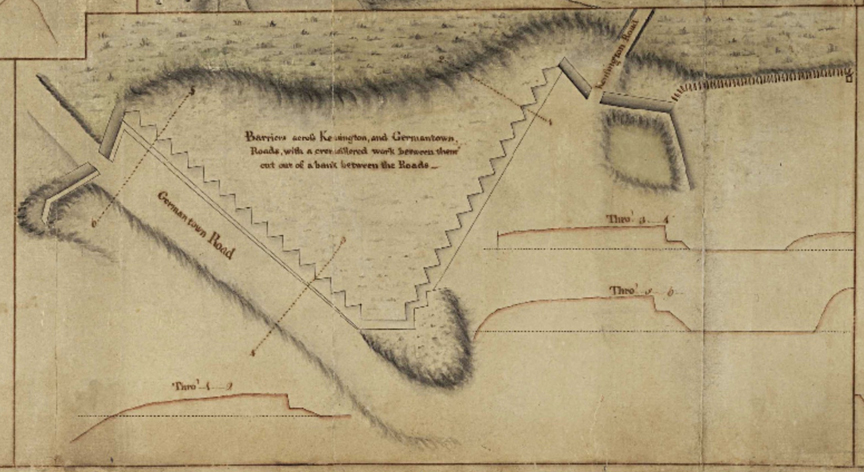

Many of these items that Roe carried from the city, particularly the fancy fabrics, were not generally intended for his neighbors. They were for the so-called “London Trade” or the illicit trading operation that took place on the north shore of Long Island. The Culper Spy Ring, and whaleboat courier Caleb Brewster in particular, employed smuggling as a cover to cross the Long Island Sound in the middle of the night as part of their espionage operation.[28] Both spying and smuggling were illegal, but the British were known to turn a blind eye to the latter.

The methodology also had Washington’s express blessing as he actively deterred Connecticut Gov. Jonathan Trumbull from taking action against the smuggling, knowing his spies were among them. Washington wrote, “The impossibility of obtaining intelligence from the enemy by any other means than giving persons some plausible pretext for entering their lines has laid us under the necessity of allowing particular people to carry in small matters of produce and to bring out goods in return.”[29]

As for Austin Roe’s trading partners in New York City, fellow spy ring member Robert Townsend was prominent among them. Townsend ran a store in partnership with Henry Oakman, known as Oakman & Townsend.[30] Information on Roe’s purchases is scarce in Townsend’s personal account books; there is only one entry that mentions specifically what he purchased: six pairs of wool cards, an imported product consisting of wire-toothed paddles used to prepare wool to be spun.[31] However, as Austin Roe and Robert Townsend had a variety of cash payments to one another and Townsend had consistent access to the same foreign goods Roe brought out of the city, Townsend’s business likely served as one of Roe’s key sources for products.

Transporting elegant items did not come without some risk. Goods leaving Manhattan were regularly subject to a thorough examination; local Loyalist John Hill was appointed as inspector for that purpose with his station located at the eastern terminus of the Brooklyn ferry.[32] This caused Roe to avoid carrying merchandise out of the city at least on some of his trips. After all, it was the documents he carried that were the most valuable items he transported to his hometown of Setauket.

To help Roe avoid suspicion for leaving the city empty-handed, Robert Townsend wrote a fake cover letter explaining that requested goods had not yet come in for Lt. Col. Benjamin Floyd.[33] A fellow native of Setauket, the ring used Floyd as a patsy, pretending they were transporting goods out of the city for his use. With Floyd in a relatively high military position, one presumes no questions would be asked about what he was ordering from the city. Now, the ring was simply pretending that Floyd’s requested items had never arrived in the city, providing Roe an alibi for his empty cart. Unbeknownst to the British and their allies, the papers below the cover letter had spy messages hidden in invisible ink.

Conclusion

Fortunately for Austin Roe, his espionage efforts and role as a carter during the war went off with relatively few hitches. He proved time and time again to be instrumental in the Culper Spy Ring operation. Most famously, he played a key role disseminating the ring’s intelligence that the British were planning an assault on the French fleet at Newport, Rhode Island. In that instance, he managed the impressive feat of transporting the information sixty miles from New York City to Brookhaven in a single day by horseback.[34] He was an essential link in the chain.

With the American victory and eventual end of the British occupation of Long Island, Roe was able to return to his trade as a joiner. Even when he became civically engaged, such as a subscriber or financier for the new local school, he would generously employ his craft to benefit those ends, like producing chairs and tables for the school.[35] While his prominent roles in local governance were also admirable—town trustee, poll inspector, overseer of highways, fence viewer, militia captain—perhaps his most valuable role yet was as a member of the Culper Spy Ring which helped shape the founding of the United States.[36] Due to continued discoveries surrounding Washington’s espionage network, the stories of Austin Roe and others can be celebrated—and told more accurately.

[1] The quotation is taken from George Washington to Nathanael Greene, January 2, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-30-02-0013. Matching intelligence supplied by Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper”) in his report of 24 December 24, 1780 appears in note 5 to George Washington to Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, December 29, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-29-02-0445.

[2] Daniel Roe, The Diary of Captain Daniel Roe, an Officer of the French and Indian War and of the Revolution: Brookhaven, Long Island, during Portions of 1806–7–8, ed. Alfred Seelye Roe, with introduction and notes by Alfred Seelye Roe (Worcester, MA: Blanchard, 1904), 12.

[3] Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger, George Washington’s Secret Six: The Spy Ring That Saved the American Revolution (New York: Sentinel, 2013), 56.

[4] George Washington, diary entry, April 22, 1790, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0001-0004-0022.

[5] Hugh Hastings, comp. and ed., Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783–1821 (Albany: J. B. Lyon, State Printer, 1901), 1:120.

[6] Washington, diary entry, April 22, 1790.

[7] Washington, diary entry, April 21, 1790.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] In the obituary of Justus Roe, Austin Roe’s son, it says he moved to Patchogue forty years earlier, which was 1807. “Died.” New-York Evening Post (New York), April 3, 1847, 2.; Austin Roe’s grandson, Austin, said that his father Justus built the original hotel and that he – Austin the grandson – had lived in a hotel his entire eighty years. With the article published in 1887, that is again 1807. “He Raged with Gen. Arthur,” The Corrector (Sag Harbor, N.Y.), March 19, 1887, 1.

[11] Peter Ross and William S. Pelletreau, History of Long Island: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time (New York: Lewis Pub. Co., 1903), 157.

[12] Based on names Austin Roe appears by, particularly the Avery family whose homestead is also located nearby in East Patchogue, it is evident he was living and recorded there as well. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Second Census of the United States, 1800, Brookhaven, Suffolk County, New York, population schedule, p. 3, image 126, roll 27, entry for Austin Roe. NARA microfilm publication M32. Austin Roe’s sister-in-law, Deborah Brewster Roe, stated he moved to a large farm on Pine Neck, which is in East Patchogue. Joseph B. Roe, “Joseph B Roe’s Notes of What Grandmother Roe Informed Him,” undated manuscript, Port Jefferson Historical Society, Port Jefferson, New York.

[13] Suffolk County, New York, Will Liber A: 325–28, Joshua Longbottom will; Surrogate’s Court, Riverhead.

[14] John Ash, The New and Complete Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 1. London: Edward and Charles Dilly; and R. Baldwin, 1775. s.v. “Joiner.”

[15] References to building windows. Abraham Woodhull, “Account Book, 1766–1800,” digital images 62, 133, 148, 175, Long Island Collection, East Hampton Library, East Hampton, NY, www.digitallongisland.org/record/36894.

[16] Reference to building a desk and a half dozen chairs: Woodhull, “Account Book” image 116; reference to mending a table and wagon in 1773: Joseph Denton, Betsey Denton, and Samuel Denton. Account Book, 1762–1802: Ledger entry for “Ostin Roe,” p. 8, Three Village Historical Society, Stony Brook, NY, liu.access.preservica.com/portal/asset/sdb%3AIO%7C991fec41-65c6-4426-96d9-cd20ac4e1543; reference to building a table and chair for the schoolhouse: “A Count [sic] of the Cost of the Schoolhouse,” January 13, 1797, manuscript sheet, Coll. HAWK/T 30.3.2, Thornton Hawkins Collection, Three Village Historical Society Archives, Setauket, NY.

[17] References to building coffins: Woodhull, “Account Book” image 62, 96; Another reference to building a coffin in 1775: Denton et al., Account Book, p. 8.

[18] Reference Austin Roe building a house dated May 17, 1790: “Contra” page, Woodhull, “Account Book” image 116.

[19] Roe, Diary of Captain Daniel Roe, 7.

[20] Reference to Austin Roe cutting timber: “Account of the Cost of the Schoolhouse,” January 13, 1797, Thornton Hawkins Collection.

[21] Austin Roe, Dr. George Muirson, and Judge Selah Strong are all recorded as farmers on Gov. William Tryon’s 1778 Oath of Allegiance list for Suffolk County. “A List of persons in Suffolk County, Long Island who took the following oath of allegiance and peaceable behaviour before Governor Tryon,” November 24, 1778, CO 5/1109, image 5 (lists Austin Roe), The National Archives (Kew, U.K.).

[22] “Austin put his cows to pasture in Drowned Meadow,” Woodhull, “Account Book” image 19. With Drowned Meadow as a tidal marsh, the cattle would have fed on marsh grasses or “salt hay.” Gordon Harris, “Gathering Salt Marsh Hay,” Historic Ipswich (blog), February 12, 2021. historicipswich.net/2021/02/12/salt-marsh-hay/.

[23] For specific examples of wood confiscation, see Huntington Town Clerk’s Archives, “Public Damages 1782–1783 p.1,” New York Heritage Digital Collections, nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16373coll130/id/356/. For a more general discussion, see John Gerard Staudt, “‘A State of Wretchedness’: A Social History of Suffolk County, New York in the American Revolution” (PhD diss., The George Washington University, 2005), 108–9.

[24] See Staudt, State of Wretchedness.

[25] Woodhull, “Account Book” image 13.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ellicott & Co., “Denim: A Mythic History,” Ellicott & Co. (blog), April 13, 2017, www.ellicott.co/blogs/posts/denim-a-mythic-history.

[28] There are several primary sources which speak to the Culper Spy Ring’s smuggling operations serving as a cover. Perhaps the clearest is in Nehemiah Marks’ counterintelligence report which states that Caleb Brewster met with James Smith at Old Man’s (modern day Mount Sinai) for goods, as opposed to Nathaniel and Phillips Roe, who Brewster met with for intelligence. Nehemiah Marks to Oliver DeLancey, December 21, 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, vol. 134, item 26, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[29] Washington to Jonathan Trumbull Sr., January 14, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-24-02-0113.

[30] Frank Sorrentino and Steve Russell Boerner, eds., Complete compilation of the transcription of Oyster Bay, N.Y. & New York, N.Y., merchant Robert Townsend’s account books, May 25, 1772 through June 1, 1785 (East Hampton, NY: East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection, February 3, 2017), 419, easthamptonlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Complete-compilation-of-Robert-Townsend-account-books-1773-1785-as-of-February-3-2017.pdf.

[31] Ibid., 357.

[32] Royal Gazette (New York), August 14, 1779, 3.

[33] Tallmadge described the situation in the postscript of a letter to Washington. Benjamin Tallmadge to Washington, July 22, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-27-02-0219.

[34] Robert Townsend’s cover letter written in Manhattan and Abraham Woodhull’s letter written in Setauket referencing Austin’s recent arrival in “great haste” are both dated July 20, 1780. Ibid., n. 2.

[35] “Account of the Cost of the Schoolhouse,” January 13, 1797, Thornton Hawkins Collection.

[36] Town of Brookhaven (N.Y.), Records of the Town of Brookhaven, Suffolk County, N.Y. [1798–1856] (Port Jefferson, N.Y.: Times Steam Job Print, 1888), 6, 19, 144, 203.

2 Comments

Neat article, Mark. I admire your determination to wade in, unsnarl, and clarify.

Excellent article. Very interesting in the Roe Tavern storyline and I appreciate this updated information even though much remains unresolved.