George Washington’s childhood is a rather elusive historical research topic. It is not that there is a lack of stories, tales, and legends published about Washington’s early years, but the task of separating authentic information from widespread mythology has compelled judicious historians to exercise tremendous skepticism when offered an assertion about his youngest days. Much of what has been written about his childhood cannot be documented with primary sources. The scholarly consensus is that the history of Washington’s childhood is fraught with a “frustrating combination of misinformation and ignorance.”[1]

One aspect is the question of Washington’s first teacher.[2] Edward Lengel edited a series of articles on George Washington, the first of which described this uncertainty.

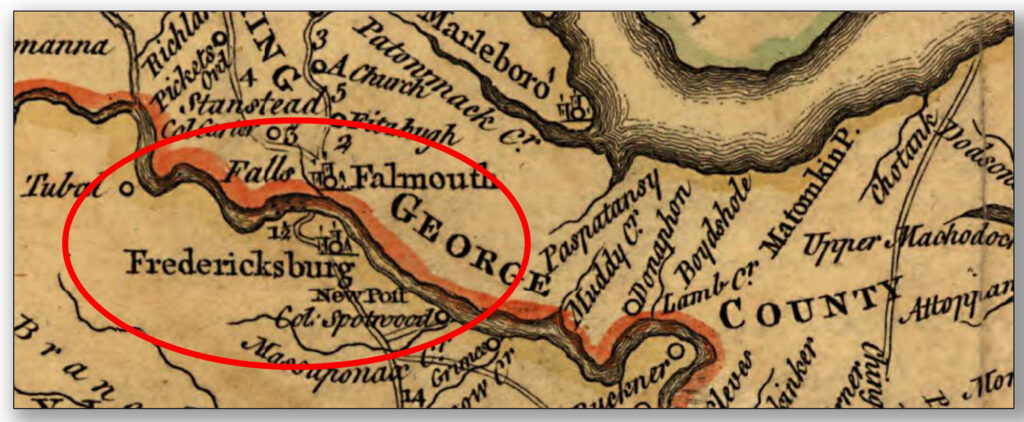

Some have stated that he was taught by one of Augustine’s [his father’s] tenants, a man by the name of Mr. Hobby. Others have suggested that he attended Reverend James Marye’s school in Fredericksburg, but there is very little direct evidence to validate either of these statements.[3]

Many nineteenth-century historians were convinced of the Hobby story, including Washington Irving, Caroline M. Kirkland, Benson Lossing and Henry Cabot Lodge.[4] Even the original “debunker” William E. Woodward affirmed the story in 1926.[5] But after John C. Fitzpatrick, editor of the Writings of George Washington whose scholarship was considered “unrivaled,’ proclaimed in 1933 that “Hobby is the fertile imagination of the Reverend Mason Locke Weems, of the ‘I-can-not-tell-a-lie’ and cherry-tree fame,” scholars became reluctant to concede Hobby’s very existence.[6] Then after Douglas S. Freeman, in 1948, wrote that the case of Hobby “cannot be accepted,” and categorized the Hobby story under the heading “Myths and Traditions,” only a small minority of scholars dared continue to include Hobby in their accounts.[7] Philip Levy described the transition:

By the end of World War II, Hobby was all but gone from most biographies, his entire story . . . having been an invention . . . Hobby only appeared alongside the Cherry Tree—both as objects of sniggering dismissal . . . There was a man named John Hobby living near Ferry Farm in the mid-eighteenth century, but that is all documents allow.[8]

However, about the same time Levy made this proclamation, the editor-in-chief emeritus of the Washington Papers (2004-2010), Theodore Crackel, proclaimed the following:

John Hobby, Washington’s first teacher, was a young convict—probably in his early twenties—transported to Virginia in 1736 on the ship Dorsetshire for stealing several silver spoons and a purse with a silver clasp from a London silversmith. Augustine (Gus) Washington, George’s father, purchased the young man’s seven-year indenture at shipside on the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia.[9]

In accord with Levy’s analysis, most biographers continue to discard Hobby. Some strong scholars, however, agree with Theodore Crackel. Willard Sterne Randall, a reputable Washington biographer, published the Hobby story in 1998.[10] Jack D. Warren still finds the Hobby history very reasonable.[11] Craig Shirley, Donald Parkerson, and Andrew Browning maintain the Hobby story today.[12] By examining an abundance of primary sources, many of which have not previously been unveiled, this study will attempt to finally resolve the mystery of Washington’s first teacher. The aim is to provide a compelling comprehensive resource that completely illuminates the issue.

Research Question One: Where does the assertion originate that George Washington had a private tutor when a child?

About 1786, David Humphreys, an aide de camp to General Washington, began to prepare a biography of the general. He furnished his manuscript to Washington to correct any errors. In the manuscript, Humphreys wrote, “his education was principally conducted by a private tutor.” Washington tacitly approved this detail, and the work was published and circulated, without pushback, during Washington’s lifetime.[13]

To identify exactly who this private tutor was, we first need to look to Washington’s stepson’s tutor. There is indubitable evidence that Washington hired the Rev. Jonathan Boucher, an Anglican minister, to tutor Jacky from 1768 to 1773.[14] During those five years Boucher and Washington lived in “habits of intimacy” and the two had “a very particular intimacy and friendship.”[15] As tutoring was their common bond, the question naturally came up at some time during those five years as to Washington’s own educational experience a child.

In his Autobiography, Boucher wrote that he had been informed that Washington was “taught by a convict servant whom his father bought for a schoolmaster.”[16] The word “bought” refers to the purchase of an indenture that would place the convict into the buyer’s service for a period of years.[17] Boucher wrote this long before any of the nineteenth-century mythmakers wrote a word about Washington’s early education. Furthermore, when Boucher wrote his Autobiography in 1786, he knew that Washington was alive and well, and was a potential reader. Boucher even wrote to Washington, transmitting a piece of his writing and expressing as a far-reaching ideal “That You will approve of all that I have written.”[18] It betrays reason, then, that Boucher would embarrass himself with an outright fabrication that one or more of his important potential readers could easily ridicule.[19] Still, these are second-hand accounts; responsible research requires us to ascertain whether Humphrey’s and Boucher’s claims can be further corroborated by other compelling primary sources.

Research Question Two: Was there a “convict servant” that Augustine Washington “bought for a schoolmaster” in the 1730s?

Augustine Washington, George Washington’s father, was intimately acquainted with the transport of convicts to Virginia, having sailed from London on a ship full of them that landed in Virginia in July 1737.[20] The following year the Virginia Gazette published a list of four indentured convicts Augustine reported as runaways, one identified as Edward Ormsby, an indentured tailor who arrived in Virginia in September 1736 aboard the ship Dorsetshire.[21]

The ship also carried a passenger/convict named Charles Peale, whose son Charles Willson Peale became one of the most honored portrait artists in early America.[22] Charles Peale’s biography, gleaned from his original letter books, identified where he landed in America:

He was banished to the colonies, a tragedy from which he never fully recovered. In 1736 or 1737, Charles Peale arrived in the small settlement of New Post on the Rappahannock River in the interior of Virginia.[23]

The convict Charles Peale, shortly after disembarking from the Dorsetshire on the Rappahannock, was engaged by Alexander Spotswood, apparently as a tutor for the Spotswood children, and subsequently advertised a child’s textbook.[24]

Research Question Three: Was there another convict on the ship Dorsetshire who also became a tutor near Ferry Farm?

Another convict aboard the Dorsetshire with Peale and Ormsby was John Hobby.[25] One reason given by historians for being uncertain about Hobby is that he “seldom appears on the records,” but significantly more about him has been discovered.[26]

Hobby was convicted in 1735 of stealing “three Tea Spoons, a Shagreen Pocket Book with Silver Clasps, and a Silver Pen and Pencil” and sentenced to “transportation” to Virginia.[27] Like Peale, the convict Hobby was amply literate and became a tutor and a schoolteacher in the vicinity of Ferry Farm. Records associated with Ferry Farm include these particulars about John Hobby:

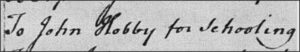

1747: “paid to John Hobby for 18 months of schooling”

May 7, 1751: “paid John Hobby for schooling 2 children.”

October 1753: “To Mr. John Hobby for schooling.”

December 20, 1753: “To Mr. Hobby for schooling”

December 25, 1754: “To John Hobby for schooling”

October 1755: “To John Hobby for schooling.”

October 1756: “To Mr. Hobby for schooling”

April 1757: “To Mr. Hobby ½ years schooling”[28]

A traveler to the region explained the phenomenon of the employment of Peale and Hobby:

Often a clever servant, or convict, that can write and read tolerably, and is of no handicraft business, is indented to some planter, who has a number of children, as a schoolmaster.[29]

Within a year of his arrival in America, Hobby was a co-signer on a deed which referred to William Strother and was signed by James Strother.[30] This is relevant insofar as it was from the estate of William Strother, Sr., that Augustine Washington purchased Ferry Farm in 1738.[31] William Strother’s son, Anthony, was a witness to Augustine Washington’s last will and testament in 1743.[32] William Strother’s uncle was William Thornton of Brunswick Parish, and John Hobby signed a 1739 indenture of “William Thornton of Brunswick Parish.”[33] A few years later, Hobby witnessed William Thornton’s will.[34]

The documents from the 1730s signed by John Hobby, referencing the Strothers and the Thorntons, place Hobby in association with residents of Ferry Farm, including one known to have been a classmate of Washington. The fact that Washington attended a “school” with other children is certain insofar as George Mason wrote to Washington as early as 1756 referencing a common friend, “your old school-fellow.”[35] Moncure Conway claimed he was privy to an unpublished Strother-family document that revealed that William Strother’s daughter Jane, raised on Ferry Farm before George’s family bought it, was one of Washington’s schoolmates.[36]

John Hobby witnessed a number of land deeds, indentures and wills for people connected in various ways to the Washington family.[37] Hobby was also appointed sexton of the Washington family’s parish, making it fairly certain that the Washington family knew him.[38] His employment by the Parish is confirmed by a February 14, 1766, indenture in which he “used as collateral his earnings in the parish.”[39] One of the principal duties of church sextons was to dig graves, which explains why Washington biographers who accept the Hobby story occasionally identify him as a grave digger.[40]

There is even more direct evidence that Washington knew Hobby. A book that Washington acquired when he was about seventeen or eighteen at Ferry Farm includes a handwritten note which reads, “I was running Hobby’s dogs.”[41] “Running dogs” was an expression used for fox hunting, a sport Washington pursued for much of his life, beginning around age sixteen.[42]

So what can we say with certainty? 1) John Hobby was a real, historical resident living near Ferry Farm during the entire time George Washington lived there; 2) Hobby was a convict; 3) Hobby was transported to the Rappahannock, near Ferry Farm, in 1736, when George Washington was nearing school-age; 4) transported convicts were ordinarily indentured upon arrival, some by Augustine Washington; 5) Hobby was paid as a tutor and teacher in the Ferry Farm region; 6) Hobby was associated with families well-acquainted with Ferry Farm, including Augustine and George Washington; 7) Hobby was appointed to be the sexton of the Washington family’s church. When coupled with Jonathan Boucher’s testimony that young George was “tutored by a convict bought by his father,” the correlation with John Hobby is overwhelming.

How, then, do these facts square with the point of view of many recent scholars that “This is an old story first put out by Parson Weems, who identified the man as John Hobby . . . However, there is no evidence that he was a tenant or former indentured servant, much less a convict, brought to Virginia by Augustine.”?[43] It appears that the main reason Hobby’s story has been so summarily dismissed is that the most prominent source of it was Mason Locke Weems, author of The Life of Washington, best known for the cherry tree legend.[44] The fact that Weems propagated the Hobby story has become nearly fatal to acceptance of it, as it has become standard among historians to eschew and ridicule Weems’ narratives.

Closing the Case with a New Revelation

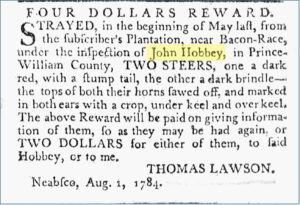

This investigation unearthed a connection never discovered before. Thomas Lawson ran an iron works in Dumfries, Virginia, and in 1771 when it came to hiring, Lawson employed a person recommended by his friend, George Washington.[45] Additionally, sometime before 1783, Lawson also hired the old King George County school teacher, John Hobby.[46] This is hardly a coincidence. Having been Washington’s first teacher would certainly have given George cause to endorse Hobby as a manager for Lawson’s plantation; a 1784 advertisement for lost cattle confirms that Hobby was employed by Lawson.[47]

John Hobby was still residing in Dumfries in 1796.[48] He had lived to see his famous student become President of the United States twice. In 1795 Dumfries also became the home of Mason Locke Weems.[49] Weems’ in-laws lived in an estate named Bel Air, about a half mile from Neabsco Creek near which John Hobby and Thomas Lawson worked and resided. The Prince William tax records insinuate, for at least three years (1795-1798), that John Hobby and Mason Locke Weems were neighbors![50]

Weems wrote about Hobby as if he had encountered him in a tavern on numerous February 22nds, “in his cups.”[51] Here is what Weems said about Hobby:

The first place of education to which George was ever sent, was a little ‘old field school,’ kept by one of his father’s tenants, named Hobby; an honest, poor old man, who acted in the double character of sexton and schoolmaster. On his skill as a grave-digger, tradition is silent; but for a teacher of youth, his qualifications were certainly of the humbler sort; making what is generally called an A. B. C. schoolmaster. Such was the preceptor who first taught Washington the knowledge of letters! Hobby lived to see his young pupil in all his glory, and rejoiced exceedingly. In his cups–for though a sexton, he would sometimes drink, particularly on the General’s birthdays–he used to boast that ’twas he, who, between his knees, had laid the foundation of George Washington’s greatness.[52]

Whether Weems received reliable information from Hobby can be convincingly determined. Later in his biography of Washington, Weems claimed that Hobby identified of one of Washington’s classmates in the Ferry Farm region, “William Bustle.”[53] If Hobby was the product of Weems’ “fertile imagination” as historians have insisted, then Weems pulled the name of Washington’s classmate out of thin air. No. According to Stafford County (Fredericksburg) records, “William Bussell” had a daughter there in 1755, which indicates that he was approximately the same age as George Washington and in the same neighborhood.[54] Bussell is listed in the same parish register as the Fowke children whom we know were tutored by Hobby, as well as the immediate family of Jane Strother, who Moncure Conway was convinced was another Washington schoolmate.[55] In the Records of King George County for the 1750s, one finds “William Bussell” listed on numerous documents with the Strothers, and several other Washington neighbors whom John Hobby was associated with in King George. This all corroborates Weems’ account provided by John Hobby. The fact that Weems spelled “Bussell” differently suggests that it was certainly an oral, not written, report from Hobby, which Weems spelled phonetically.

It is clear that what Weems wrote about Hobby is corroborated by several verifiable sources. The fact that Weems refers to “old Hobby” is further indication that Weems knew him at Dumfries, as he was not at all “old” when he tutored in Brunswick Parish.

After evaluating the abundance of evidence that predates Weems, and the evidence of the propinquity of Weems to Hobby, a judicious historian is compelled to concede that Weems’ account of Hobby is, on the whole, authentic, and that modern biographers who consider the tutor Hobby as “invented,” “fabricated,” or “imagined” by Weems have missed the evidence. The preponderance of original records confirms Crackel’s allegation that John Hobby was real; he was a convict and indentured as a tutor; that Hobby was a sexton at Brunswick Parish; that Hobby was Weems’ neighbor; and, as Jack D. Warren believes, “there is little reason to doubt” Hobby was George Washington’s first teacher.[56]

[1] Joseph Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2005), 7.

[2] Kevin J. Hayes, George Washington: A Life in Books (Oxford, 2017), 17, “The story of Washington’s education is shrouded in mystery.”

[3] Jessica E. Brunelle, “The Youth of George Washington,” in A Companion to George Washington, 1-14, edited by Edward G. Lengel (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 10.

[4] Washington Irving, Life of George Washington: Early Life, Expeditions, and Campaigns (1855), 14-15. Caroline M. Kirkland, Memoirs of Washington (1857), 42-43. Benson Lossing, Life of Washington: A Biography, Personal, Military, and Political, vol. 1 (New York: Mason Brothers, 1860), 24. Henry Cabot Lodge, George Washington, vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1899), 46.

[5] William E. Woodward, George Washington: The Image and the Man (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1926), 23.

[6] John C. Fitzpatrick, George Washington Himself: A Common-sense Biography Written from His Manuscripts (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1933), 517. Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, Vol. 50 (1941), 13-14.

[7] Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography, vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948), 64n. Freeman seemed to be dismissing the rumor of Hobby as the sexton of Truro Parish near Mt. Vernon which Hobby certainly was not. This likely arose from the tremendous confusion in the secondary literature wherein some speculated that the sexton of Truro Parish, William Grove, was one and the same person as John Hobby, which he was not. E.g., Memoirs of the Long Island Historical Society, Vol. 4 (1889), xxix-xxx.

[8] Philip Levy, George Washington Written Upon the Land (West Virginia University, 2015), 43.

[9] Theodore Crackel et al., “George Washington’s Use of Trigonometry and Logarithms,” Proceedings of the Canadian Society for History and Philosophy of Mathematics (2013): 2.

[10] Willard Sterne Randall, George Washington: A Life (1998), 22.

[11] Jack D. Warren, “The Childhood of George Washington,” The Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine 49:1 (1999), 5801.

[12] Donald & Jo Ann Parkerson, Transitions in American Education: A Social History of Teaching (RoutledgeFalmer, 2014), 66; Craig Shirley, Mary Ball Washington: The Untold Story of George Washington’s Mother (Harper, 2019), 122; Andrew H. Browning, Schools for Statesmen: The Divergent Educations of the Constitution’s Framers (University of Kansas, 2022).

[13] David Humphreys, David Humphreys’ “Life of General Washington”: with George Washington’s “Remarks” (University of Georgia, 1991), reprint of the 1786 manuscript in the collection of the Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia, PA, 101; Washington’s original feedback to Humphreys’ biography is in the collection of the Mt. Vernon’s Ladies Association. Jedidiah Morse published the sketch in 1789 and in future years in The American Geography; it showed up overseas in H.D. Symonds, The Monthly Visitor, and Entertaining Pocket Companion, Volume 1 (London, 1797), 325.

[14] George Washington to Jonathan Boucher, May 30, 1768. Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (Penguin, 2010), 155.

[15] Jonathan Boucher to George Washington, May 25, 1784. Jonathan Boucher, “Autobiography” (March 1786) in Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 1738-1789 (1797), 48.

[16] Though the title suggests it was written after 1789, the manuscript is titled “Autobiography of Jonathan Boucher, March 1st, 1786. Ash Wednesday.” Reminiscences, 1. Boucher, op. cit., 49.

[17] Emily Salmon, “Convict Labor During the Colonial Period,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities (2020).

[18] Jonathan Boucher to George Washington, 8 November 1797.

[19] This claim in Boucher’s Autobiography has been evaluated similarly in the past. “The truth regarding Washington’s tutor must have been known to Boucher… Who was more likely than Boucher to know whether Washington’s teacher was a convict?” The Nation: A Weekly Journal Devoted to Politics, Literature, Science, Drama, Music, Art, Industry, Vol. 48 (1889), 828 & Vol. 64, no. 1659, 284. Boucher’s first experience in America was in the 1750s tutoring on the Rappahannock River across from King George County, not far from where Hobby taught. W.C. Ford, “Letters of Jonathan Boucher to George Washington,” New England Historic and Genealogical Register, Vol LI (1898), 58.

[20] Virginia Gazette, July 22, 1737, 4.

[21] John Peters, bricklayer; Richard Martin, sailor; Richard Kibble, carpenter; and Edward Ormsby, tailor, are mentioned by Augustine Washington in the Virginia Gazette, June 9, 1738, 4, being convicts who tried to run away. Peters’ surname is first found in Va. Gaz., Nov. 18, 1737, having come from Kent on the same ship, and tall in stature. His status as a convict aboard the ship Forward, is found in Peter Wilson Coldham, The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614-1775 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co., 2002 [hereafter Bondage]), 594, 623. Virginia Gazette, June 9, 1738.

[22] Bondage, 617; David C. Ward, Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic (University of California Press, 2004), 5, “Charles Peale was duly embarked on the ship Dorsetshire.”

[23] Charles Willson Peale, The Collected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: A Guide and Index to the Microfiche Edition (New York: Kraus Microform, 1980), 4.

[24] Charles Coleman Sellers, Charles Willson Peale, Part 1 (American Philosophical Society, 1947), 26, speculates that Spotswood “had taken the young man into his household as a tutor.” Virginia Gazette, July 21-28, 1738.

[25] Bondage, 394.

[26] Virginia Quarterly Magazine, Vol. 24, no. 4 (1948), 235.

[27] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, Sessions paper (17350702), www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/17350702.

[28] Stafford County, Virginia Deed Book O, 1748-1763, 145. “The Estate of Chandler Fowke.” his indicates that Hobby was a teacher in 1745. Inventory Book 3, King George County, Virginia, 75-78. “The Estate of Abraham Kinnian,” May 7, 1751. Abraham Kinnian/Kenyon was the owner of “Albion,” which was willed to his daughter Frances, who married Anthony Strother, uncle of Jane. Fiduciary Accounts Book 3, King George County, Virginia 1740-1765, 117 – 118; account of Elizabeth Moon, ward of Richard Tutt (her uncle).

[29] Edward Kimber, “Itinerant Observations in America” (1746) in Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. 51 (1956), 335. Boucher concurred in 1773, preaching that 2/3rds of tutors in the colonies were “indented servants or transported felons.” Boucher, A View of the Causes and Consequences of the American Revolution (1787), 184. Without proof, Bradley T. Johnson, General Washington (1894), 14, surmised that Hobby also had been a “university man” in England prior to his exile.

[30] Spotsylvania County, 1721-1800: Being Transcriptions from the Original Files at the County Court House, Volume 1 (1905), 144.

[31] King George County, Virginia Deed Book 2, 220-225.

[32] George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Will of Augustine Washington, April 11, 1743.

[33] King George County Deed Book 2, 294-295.

[34] King George County, Virginia Will Book A1, 153-154.

[35] George Mason to George Washington, June 12, 1756.

[36] M.D. Conway, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 78 (1889), 738-739.

[37] Spotsylvania County, 1721-1800: Being Transcriptions from the Original Files at the County Court House, Vol. 1, 153. S. J. Quinn, The History of the City of Fredericksburg, Virginia (1908), 42. N.b. another Trustee was Ira Thornton and Hobby witnessed an indenture and will of William Thornton. 1735-1743 King George County, Virginia Deed Book 2, 366-368, 470-474, and book 3, 75. George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Augustine Washington, April 11, 1743, Will. Deeds 4, 1752-1765, King George County, Virginia. “Will of Will Rosser,” King George County, Virginia Will Book Al, 196-197; “Will of Mary Meese,” Stafford County Va Will Book M; 1729-1748, 513-515. “Will of Anne Redman,” King George County VA Wills, 1752-1780, 77-78; “Will of John Steward,” King George County, VA Wills, 1752-1780, 288-290. Virginia County Court Records: Deed Abstracts of King George Co., VA, 1753-73, quoting King George Co., VA Deed Bk, 643-64.

[38] William Allason, Ledger Book, 1767; Ledger E, 3. This is corroborated by the 2014 Master Interpretive Plan of the Falmouth District: “the Washington family did attend the Brunswick Parish Church, where Hobby was the sexton.” cdn.staffordcountyva.gov/Planning%20and%20Zoning/architectural%20review%20board/Master%20Interpretive%20Plan.pdf; also corroborated by The Register of Overwharton Parish, Stafford County, Virginia, 1723-1758 (1961), 172.

[39] Deeds 5, 1765-1783, King George County, Virginia.

[40] Gregory Lewin, A Summary of the Law of Settlement (1827), 459.

[41] Peter Lillback, George Washington’s Sacred Fire (Providence Forum, 2006), Chapter 7, note 17.

[42] www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/athleticism/foxhunting (Accessed May 29, 2025).

[43] Robert Previdi, Presidential Studies Quarterly; Vol. 29, Iss. 2 (1999), 498.

[44] Mason L. Weems, Life of Washington (1808). Hereafter LOW.

[45] Virginia Governors Executive Papers – Thomas Jefferson, Prince William County, Henry Lee, Sr. to Thomas Jefferson from Henry Lee, Sr., 9 April 1781; also Virginia Gazette, Number 429, 28 July 1774, 4 column 1; Tayloe and Lawson were both original trustees of the town of Dumfries. 2014 Town of Dumfries Comprehensive Plan, 50. The Washington family was deeply networked with the Iron industry which made George’s connection with Lawson very natural. See Lawson to Washington, June 19, 1761.John Posey to George Washington, May 25, 1771.

[46] 1783 & 1787 Personal Property Tax List, Prince William County, VA; The 1783 list indicates Hobby was “Laws. overser.” The 1787 List includes “Thomas Lawson & John Hobby” together in the same space; Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser, Sept. 16, 1784; John Hobby also witnessed an indenture in Prince William in 1791 that referred to “Dumfries Road.” Deed Abstracts of Prince William County, VA 1791-1796 Ruth and Sam Sparacio, eds. (1993), 25. On April 26, 1768, George Washington and his family “lodged” at Mr. Thomas Lawson’s home. George Washington, Diary, April 26, 1768. A letter to George Washington from Thomas Lawson, June 19, 1761, is in the Washington Papers. Washington arbitrated a dispute between Lawson and John Graham. George Washington, Diary, April 19, 1770.

[47] Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser, September 16, 1784.

[48] 1796 Personal Property Tax List, Prince William County, VA.

[49] In 1795 Weems married Washington’s second cousin, Frances Ewell, at Bel Air, in Dumfries. Paul L. Ford, Mason Locke Weems: His Works and Ways. In Three Volumes, Volume 2, xx.

[50] John Hobby is recorded on the tax lists of Dumfries until 1798. Weems took residence there in 1795.

[51] LOW, 12. The idiom, “in his cups,” means drunk. Christine Ammer, The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms: American English Idiomatic Expressions & Phrases (2013), 230.

[52] LOW, 12.

[53] LOW, 24.

[54] “Baptism of Bussell, Agathy, Daughter of William, October 26, 1755,” Overwharton Parish Register, 1720-1760 (1899), 24.

[55] Ibid., 54-55.

[56] Jack D. Warren, “The Childhood of George Washington,” The Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine 49:1 (1999), 5801.

4 Comments

Thank you for this well-researched article!

Thank you Mr. Gardiner for evaluating and reporting this information you have clearly explained. One question:

In Westmoreland Co., Va., there is a historical marker titled “History at Oak Grove” that states:

“Here George Washington, while living at Wakefield with a brother, went to school, 1744–1746. Here Union Cavalry came on a raid through the Northern Neck, May 1863. Several miles north of this place, James Monroe, fifth President of the United States, was born, 1758.” (Marker #67-J)

How does this part about GW fit in with the story you tell above? Is there truth to it? It was erected in 1928, along State Route 3.

Great article! Well written and well researched. Thank you!

This is superbly researched and I think you perfectly settled the matter. Excellent article!