Introduction

As America enters its semiquincentennial year in 2026, there will be numerous celebrations and remembrances of the nation’s founding. The names George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and others will ring familiar as patriots who drafted key documents such as the Declaration of Independence, rode across the countryside to alert colonists that “the British are coming,” and organized and led a grass-roots army to fight for American independence. Lesser known but of tremendous importance in telling the full story of the Revolution are Crispus Attucks, William Lee, Agrippa Hull, and other Black patriots. This article focuses on Black patriots of the American Revolution in order to increase awareness of their crucial role, presenting an overview of key individuals, resources to guide readers in where to learn more, and three specific teaching strategies, each supported by a model that teachers can use in or adapt to their own teaching context.

The Role of Black Patriots in the American Revolution

It is important that study of the American Revolution be inclusive of Black patriots and make visible the key role that African Americans, both enslaved and free, played in the Revolutionary War. Historians estimate that five thousand African Americans, some while still enslaved, fought for the new nation’s independence from Great Britain.[1] Crispus Attucks, for example, was the first man to die for the American rebellion against the British.[2] Attucks was a sailor of mixed African and Indigenous ancestry who was in a group protesting against British troops quartered in Boston. A riot broke out, and in the midst of the chaos British soldiers fired into the crowd. This event, known as the Boston Massacre, resulted in five deaths, including that of Crispus Attucks.

William Lee was a valet who served seven years alongside George Washington from Valley Forge to the siege of Yorktown.[3] Lee continued to serve Washington during his eight-year presidency and was granted his freedom in Washington’s will in recognition of his “faithful services during the Revolution.”[4]

Prince Dunsick was kidnapped in Africa (the specific nation is not known) and sold into slavery as a child.[5] He was enslaved in Massachusetts and was enlisted in the Continental Army as a substitute for his enslaver. He is representative of the many enslaved men forced to enlist by their enslavers.

Born free in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Agrippa Hull chose to enlist in the Continental army, desiring to fight for the cause of liberty and having hope that an American victory would lead to the end of slavery.[6] Two military leaders, including the famed Polish engineer Col. Tadeuscz Kosciuszko, noted Hull’s intelligence and good humor, and personally selected him to serve as their orderly, a role that came with immense responsibility and required trust.[7] After the war, Hull returned to Stockbridge and became the “largest Black landowner … [amassing] more wealth than forty percent of the town’s white householders.”[8]

Prince Hall was a free black abolitionist who encouraged enslaved and free blacks to serve in the Continental Army,[9] believing “if blacks were involved in founding the new nation, it would aid in attaining freedom for all blacks.”[10] In his ongoing pursuit of freedom, he petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature to end slavery as early as 1777.[11] Hall “rooted his argument in a powerful vision of natural rights, arguing that slavery itself violated the ‘natural and inalienable right to freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind.’”[12]

Also of note is famed poet Phillis Wheatley. She “had an unusual experience in bondage: Her owners educated her and supported her literary pursuits. In 1773, at around age 20, Wheatley became the first African American and third woman to publish a book of poetry in the young nation. Shortly after, her owners freed her.”[13] She then went on to tour America and Europe to speak out against slavery and for the cause of freedom for all people.

Researching the Role and Contributions of Black Patriots

Having piqued student interest and curiosity regarding Black patriots who served in the Revolutionary War by sharing about Crispus Attucks, William Lee, Prince Dunsick, Agrippa Hull, Prince Hall, and through her words, Phillis Wheatley, teachers should next encourage students to go deeper by having them research additional stories and respond in ways that help students learn, envision and personalize those stories. Though sometimes teachers are hesitant to use Wikipedia, it has excellent resources for this assignment, at least as a starting point. On Wikipedia, “Notable Black Patriots” provides names and links to detailed information on more than forty Black patriots.[14] Five additional resources are useful for this assignment. The National Park Service’s “African Americans in the Revolutionary War” provides profiles of nine Black patriots as well as additional related articles of interest.[15] Two particular articles that will help students move beyond individual stories and see a bigger context include “Patriots of Color in Massachusetts”[16] and “Enslavement and Enlistment” which examines “how changing Massachusetts laws concerning the enlistment of men of color in the military affected their opportunities to serve during the Revolution as well as their chances of being emancipated, if enslaved.”[17] George Washington’s Mount Vernon website features “Give Me Liberty: African Americans in the Revolutionary War.”[18] In addition to sharing the story of William Lee and other Black patriots, the site talks about the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, a 225-man regiment that included 140 Black soldiers. The website History, a spinoff from the History Channel, hosts the graphically rich “7 Black Heroes of the American Revolution.”[19] This site includes videos and historic images curated by Alamy, Getty and more that could be useful for students who want to include visual elements in their responses. PBS’s “Africans in America: The Revolutionary War” details the history of the Revolutionary War.[20] The site includes a timeline and big picture narrative about America’s history leading up to, through and past the Revolutionary War. It also includes links to specific Black patriots who served in the Continental Army both on land and at sea. Finally, the Journal of the American Revolution (JAR) website has a myriad of in-depth, well-researched articles on various aspects of Blacks, both men and women, in the Revolutionary War era. The best way to find relevant articles is to go to the “Search JAR” box on either the Home or Archives page and enter any of the following key words: “Black,” “African,” “slave,” and “slavery.” Another option is to enter known names, regiments, etc. into the search tool.

Student Expressions of New Learning

Once students have conducted research to learn about one or more Black patriots, the next step is to provide guidance that leads to deeper understanding and sharing. There are a variety of ways that students can report and express what they have learned. They could create a poster presentation, PowerPoint, or Powtoon. They could focus on details of the courage and sacrifice made by the patriot they researched and compose a letter of gratitude to that individual. They could imagine themselves as the patriot they researched and write a letter, poem, diary or journal entry from that person’s perspective. What has that patriot seen, done and experienced? What has gone well? What caused them heartache? Who did they love or loathe and why? As students compose such entries, teachers should emphasize the integration of factual knowledge gained from student research. Responses that combine both factual information and perspective-taking contribute positively to head knowledge and heart knowledge. The section that follows details three specific examples of student projects with supporting models that teachers may find useful in their classrooms. Below is a model of the first project, offering an example diary entry from the perspective of William Lee, the African American patriot who served as valet to Gen. George Washington.

Project 1: Example Diary Entry from the Perspective of William Lee

| This is a fictional diary entry written from the perspective of William Lee, valet to Gen. Washington during the Revolutionary War. The entry is written nine days after the passing of George Washington at Mount Vernon. This imaginary diary entry integrates factual information from two websites: George Washington’s Mount Vernon (“William (Billy) Lee”) and Wikipedia (“William Lee (valet)”).

From the Diary of William Lee (1750-1810), valet to George Washington Christmas Day, 1799 Nine days ago he did die and on that day did I, now 49 years old, gain my freedom as the general did free me in his will, praising me for my faithful services during the Revolution. The Revolution, yes, but for years before and after as well. It is hard to believe and something I want to be remembered of me, that I was the personal valet of General George Washington and President George Washington. Some thirty and one years have passed since the general purchased me via a promissory note. I heard him tell that that note was for 61 British pounds, the currency of the time. It still baffles me how money can be ascribed to a human life. I believe one day this will change, though it may take another war to make that happen. The day Washington purchased me, he also purchased my brother Frank and two other slaves. Thankfully Frank and I were given house jobs—I as the valet and Frank as the butler. People might be surprised to know that not only did I manage the general’s equipment, I also helped him bathe and dress and even tied the ribbon in his hair each morning. Throughout the war years—all dreadful eight of them—I was at Washington’s side. He chose me because I was excellent at horsemanship, something I proved on fox hunts where I was in charge of blowing the horn. Oh, how Washington loved to hunt! From Valley Forge to the siege of Yorktown, I rode by his side in the thick of every battle, ready to find him a spare horse or hand him a telescope or whatever he might need. It was glorious when the war ended—no more fighting, guns and roars of canons, though they continue in my nightmares to this day. How eager I was for his inauguration on that bright day of 1789, but a bad fall while working at the office in Alexandria resulted in my not being able to attend. Though I have struggled with pain all these years since, I am grateful that doctors were able to design a steel brace making it so I could continue working for Washington as he changed roles from General to President. As my infirmity progressed and my mobility decreased, I became a shoemaker at Mount Vernon. Alcohol has provided some relief, but one much be careful with it, for it can also become a private devil! The whole household has seen the General’s demise in these weeks as he has been bedfast, and the doctors have bled and leeched him multiple times. When he finally passed, Martha herself, with tears in her eyes, came to me and told me I had been released, would receive a pension of 30 dollars a year and that I was welcome to stay at Mount Vernon if I so desired. I was the only one granted my freedom that day. Others enslaved will have to wait until Martha passes. For me there is no question. Near Washington is where I belong. One day I will die and be buried here, but in the meantime, I will enjoy life with my wife Margaret. Oh, beautiful Margaret, born a free black woman in Philadelphia, how she brings joy to my days and will help me to embrace this new freedom. I know she will help me, for she loves me and I her. |

Trifold Brochure and Written Explanation

The trifold brochure is a valuable way for students to examine and present findings about something they have researched. Such a brochure could be used to get into the mind of a fictional character, but in this study of Black patriots, the brochure’s focus is relaying key facts and information about a real person’s life. In creating the brochure, students should include at least five pictures or drawings and at least eight paragraphs, each with a topical header. The first paragraph of the brochure should include the name and a brief description of the patriot. The last paragraph should focus on patriot’s legacy. The topics of the remaining paragraphs are up to the student. Good things to include may be free or enslaved status, childhood, family details, where the person lived, hardships, sacrifices and accomplishments.

Given that the specific format is a trifold brochure, it is important to pay attention to layout so that when it is printed two-sided and folded, the first paragraph is on the front and the final paragraph is on the back center. These brochures could be created by hand or by using programs like Microsoft Word or Canva. The example below provides a sample trifold brochure created using Canva and focused on Agrippa Hull. Accompanying the brochure, students should compose a two-paragraph essay. The first paragraph should provide an explanation of the choices made for the brochure – the topics, focus and images. The second paragraph is metacognitive in nature as students explain what they learned or perceived more clearly as a result of this activity. At the end of the essay, students should list what sources they used to find information on the Black patriot and cite images used in the brochure. An example student essay corresponding to the brochure on Agrippa Hull follows the trifold.

Project 2: Example Trifold Brochure featuring Agrippa Hull

| Explanation of Trifold Character Brochure for Agrippa Hull

Why I chose what I did: For my brochure I chose to focus on Agrippa Hull who was a free Black man who enlisted in the Continental army at the age of 18 and served as the orderly of both Gen. John Paterson and the famed Polish engineer Col. Tadeusz Kosciuszko. After the war, Agrippa Hull returned to his home of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he became a landowner, married, had four children and ran a farm and boardinghouse. I organized my brochure using the following categories, which are presented in chronological order: 1) Agrippa Hull; 2) Enlistment; 3) Gen. John Paterson’s Orderly; 4) Valley Forge; 5) Col. Tadeusz Kosciuszko; 6) A Dangerous Prank; 7) Hudson River Valley to South Carolina; 8) After War’s End; 9) Wit and Wisdom; 10) West Point; 11) Legacy. The portrait of Agrippa Hull dates to 1848 and is by an unknown artist who based the painting on Anson Clark’s daguerreotype taken several years earlier. I included a picture of George Washington and Tadeusz Kosciuszko with the flags of the United States and Poland in order to show the important role the men’s collaboration played in winning the American victory. I found a picture of an early 1800s pistol with gold inlay to depict the gift Kosciuszko gave to Agrippa Hull at the end of the war. The two had spent over four years together in battle and developed a close friendship. Since there was no photography during the time of the Revolutionary War and I could not find any paintings of Black families on eighteenth century Massachusetts farms, I used my own imagination and put in descriptors into Gemini of what I thought the family and property might look like. From the initial image generated by Gemini, I made multiple edits to arrive at the one included in the “After War’s End” section of the brochure. Finally, I was thrilled to find an 1830 view of The United States Military Academy at West Point. The timing of this portrait is within one year of when Agrippa Hull went there to share stories about his time with Col. Kosciuszko who was being honored on the occasion. What I learned: Creating the trifold brochure caused me to think carefully about what was most important to share about Agrippa Hull’s life. In order to create a brochure that would make logical sense and be aesthetically pleasing, I had to think about what information should go together and what illustrations would emphasize key points. Having done this activity, I feel like I know highlights of Agrippa Hull’s life well enough that I could share them with others. What surprised and impressed me the most in doing the research for this project was seeing how Agrippa Hull, due to his intelligence and good humor, won the favor of influential military leaders including Gen. Tadeusz Kosciuszko whose engineering skills – building forts and bridges and planning marches through mountains, ravines and forests – were influential to the American victory. Kosciuszko relied on Hull, not only as his personally selected orderly responsible for delivering messages, preparing uniforms and tending horses, but also as a trusted friend. Hull could have stayed back in Stockbridge and not participated in the fight for independence, but believing in the cause of liberty and hoping that a free United States would bring an end to slavery, he enlisted. He survived the brutal winter at Valley Forge, marched over 5,000 miles from the Hudson River Valley all the way to South Carolina to help secure American victory. He was a man who confronted racism with wit and wisdom, and just as he persevered through the war years, so he did after the war as he established a home and family. Agrippa Hull contributed to the establishment of this nation that I have the privilege to enjoy today. Where I found information for my brochure: Woelfle, Gretchen, Answering the Cry for Freedom: Stories of African Americans and the American Revolution, (Honesdale, PA: Calkins Creek, 2016, pp. 29-37). The direct quote in the “Wit and Wisdom” paragraph is from page 36. Where I found the images for my brochure: 1. Portrait of Agrippa Hull[21] https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/agrippa-hull.htm and information[22] from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h8.html 2. Washington and Kosciuszko with flags of America and Poland[23] 3. Revolutionary War Era Flintlock Pistol with Gold Inlay[24] https://historyimagined.wordpress.com/2016/06/10/pistols-for-the-uninformed/ 4. Black family on early 1800s Massachusetts farm I created that myself using Gemini, https://gemini.google.com/u/1/app 5. 1830 View of West Point Military Academy[25] https://www.pictorem.com/2094324/1830%20View%20of%20West%20Point%20Military%20Academy.html |

Story Portrait and Written Explanation

A story portrait is an activity that requires students to focus on the main point of a story and to represent their understanding in a one-page graphic design that resembles a framed picture or portrait.[26] In the context of studying Black patriots, the “story” is what research has shown about the patriot’s life. The story portrait can be a drawing with an ink pen, colored pencils, markers, or may be created using images from magazines or printed from a computer. The portrait could also be created entirely online using a program such as Canva.

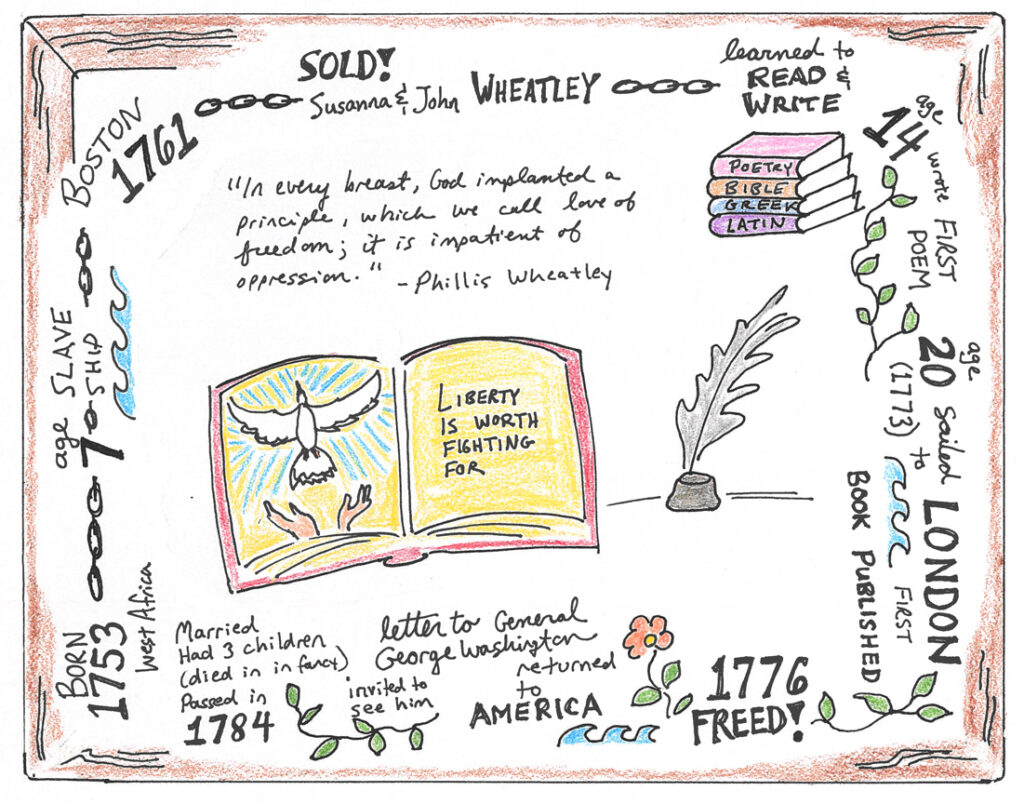

The first step in creating a story portrait is to draw a border or frame around the “portrait” based on a significant or important idea from the short story. The border may consist of words, pictures or both. Inside the border in the “portrait” area, students should draw a symbol for the main idea or point they want to emphasize about the patriot’s life. After generating the symbol that represents the “big idea” of the patriot’s life and/or contribution, students should consider a related theme and write it in a phrase or sentence within the frame. Finally, students will find a quote that blends the symbol and the theme statement together and write the quote somewhere on the portrait to complete the picture. It is important to note that the quote does not need to be said by the patriot but must ring true as something important to the patriot. Below is an example story portrait focused on Phillis Wheatley. After creating the story portrait, the student should compose an explanation of at least two paragraphs explaining their drawing. As part of this, students should be sure to discuss the main idea of the patriot’s life and provide context for the quote included in the portrait. At the end of the essay, students should list what sources they used to find information. An example explanation focused on Phillis Wheatley follows the story portrait.

Project 3: Example Story Portrait featuring Phillis Wheatley

| Explanation of Story Portrait for Phillis Wheatley

My story portrait focuses on the life of Phillis Wheatley who was the first African American to have their poetry published. I wanted to include many important details from Phillis Wheatley’s life and found the “frame” the best place to do that. My story portrait traces key events in Wheatley’s life and should be read starting in the lower left corner where it says “Born 1753 West Africa.” From there, go up the left side. There you will find that Wheatley was sold into slavery at age seven. I included chains to connect the events and waves to show that she was shipped across the ocean in a slave ship. The next big year in Wheatley’s life was 1761 when she arrived in Boston and was sold to Susanna and John Wheatley, which is how she got her last name. Her first name, Phillis, came from the name of the ship that brought her into the harbor at Boston. Reading across the top of the frame, you will see more chains since Wheatley was enslaved, but then I included a vine of leaves showing something better than chains as Phillis learned to read and write. Specifically, she read the Bible and poetry and learned to read and speak Greek and Latin. At age 14 Phillis Wheatley wrote her first poem, and her enslavers recognized her talent. In 1773 at age 20, Phillis sailed to London with the Wheatley’s son. The purpose of their trip was to find a publisher for her poems. While in London, the Wheatleys granted Phillis her freedom. It is thought they did this fearing she might not return to America otherwise, since in London she could live as a free person. In 1776 Phillis returned to America and wrote a letter to General George Washington. The war was still going on, and Washington was not yet president. General Washington saw how passionate Phillis was for the cause of freedom and invited her to meet him in person. From here Phillis Wheatley’s fame continued to grow. She married and had three children, though tragically all died in infancy. She passed in 1784 at the age of 31 and was buried with her third child. I chose an open book and quill pen as the symbols to represent Phillis Wheatley since she was known as a great writer. On the left page of the book I drew a picture of a dove being released as a symbolic of freedom. I chose “Liberty is worth fighting for” as the theme statement because through her writings Phillis promoted freedom. It is likely because of her own enslavement that she so treasured freedom – both personal freedom and the freedom of nations from tyranny, such as America’s freedom from the tyranny of Great Britain. Finally, the quote I chose represents freedom, stating that it is “in every breast,” implanted there by God, and it is “impatient of oppression.” This quote is in Phillis Wheatley’s own words in a letter she wrote to Reverend Samson Occom in 1774. Where I found information on Phillis Wheatley 1. https://www.amrevmuseum.org/news/in-the-news-1774-newspaper-printing-of-phillis-wheatley-s-letter-rebuking-slavery[27] |

Closing Thoughts

Through the resources and activities in this article, students gain exposure to the often overlooked but crucial role of Black patriots in the American Revolution. Besides gaining head knowledge, the activities help to promote heart knowledge – a sense of deeper understanding, empathy, and respect for the contributions made by African Americans, both enslaved and free, to secure the independence of a new nation. Those wanting to go deeper into this aspect of history will likely be interested in The Seeds of America trilogy by Laurie Halse Anderson that begins with Chains and then goes on to Forge, the title a reference to Valley Forge, and Ashes[29] which examines the transition of African Americans, many still in flight from enslavers, after the end of the American Revolution on October 19, 1781 when British Gen. Charles Cornwallis surrendered to Gen. George Washington at Yorktown. Also deeply compelling is M. T. Anderson’s duology The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing: Volume I – The Pox Party and Volume II – The Kingdom of Waves.[30] This series comes from the unusual perspective of Octavian, an enslaved African who is sheltered from the outside world and initially does not see himself as a slave given that he lives with his mother and a group of scientists and professors at the Novanglian College of Lucidity where he receives a classical education. In volume two, Octavian has escaped the college and opts to serve in the British navy, fighting against the Continental Army. Whether focusing solely on shorter biographies or teaching those in tandem with in-depth works of historical fiction, teachers using the strategies shared in this article will broaden student understanding of the complexity of the American Revolution and the important role of Black patriots in securing the nation’s independence.

[1] “The Revolutionary War,” Africans in America: Revolution, PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html.

[2] “Crispus Attucks,” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/people/crispus-attucks.htm.

[3] “William ‘Billy’ Lee,” American Battlefield Trust, 2024,

www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/william-billy-lee.

[4] “Give Me Liberty: African Americans in the Revolutionary War.” George Washington’s

Mount Vernon, www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/african-americans-in-the-revolutionary-war/.

[5] “Prince Dunsick,” National Park Service. www.nps.gov/people/prince-dunsick.htm.

[6] Gretchen Woelfle, Answering the Cry for Freedom: Stories of African Americans and the American Revolution (Honesdale, PA: Calkins Creek, 2016), 31.

[7] Ibid., 31-32.

[8] “Agrippa Hull,” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/agrippa-hull.htm

[9] “Prince Hall,” Africans in America: Revolution, 1998,

www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2p37.html.

[10] “Prince Hall,” Wikipedia, last modified March 10, 2024,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Hall.

[11] “Petition to the Massachusetts Legislature (1777).” National Constitution Center. 2024.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Colette Coleman, “7 Black Heroes of the American Revolution,” History, www.history.com/news/black-heroes-american-revolution.

[14] “Notable Black Patriots,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Patriot.

[15] “African Americans in the Revolutionary War,” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/chyo/learn/historyculture/african-americans-in-the-revolutionary-war.htm.

[16] John Hannigan, “Patriots of Color in Massachusetts,” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/articles/000/john-hannigan-patriots-of-color-paper-1.htm.

[17] John Hannigan, “Enslavement and Enlistment,” National Park Services, www.nps.gov/articles/000/john-hannigan-patriots-of-color-paper-3.htm.

[18] “Give Me Liberty: African Americans in the Revolutionary War,” George Washington’s

Mount Vernon, www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/african-americans-in-the-revolutionary-war/.

[19] Colette Coleman, “7 Black Heroes of the American Revolution,” History, www.history.com/news/black-heroes-american-revolution.

[20] “Africans in America: The Revolutionary War,” PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html.

[21] “Agrippa Hull,” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/agrippa-hull.htm.

[22] “Historical Documents: Portrait of Agrippa Hull, 1848,” PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h8.html.

[23] “168. Jexzcze Polska Nie Zginela, George Washington, Tadeusz Kosciuszko,” Dom Aukcyjny Ostoya, www.aukcjeostoya.pl/produkt/343052/168-jeszcze-polska-nie-zginela-george-washington-i-tadeusz-kosciuszko/.

[24] Caroline Warfiled, “Pistols for the Uninformed,” History Imagined: For Readers, Writers, & Lovers of Historical Fiction, June 10, 2016, historyimagined.wordpress.com/2016/06/10/pistols-for-the-uninformed/.

[25] “1830 View of West Point Military Academy,” Pictorem, www.pictorem.com/2094324/1830%20View%20of%20West%20Point%20Military%20Academy.html.

[26] Jacqueline Glasgow, Using Young Adult Literature: Thematic Units Based on Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences (Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, 2002).

[27] “In the News: 1774 Newspaper Printing of Phillis Wheatley’s Letter Rebuking Slavery,” Museum of the American Revolution, March 29, 2022, www.amrevmuseum.org/news/in-the-news-1774-newspaper-printing-of-phillis-wheatley-s-letter-rebuking-slavery.

[28] Charita Gainey, “Why did Phillis Wheatley Disappear?” TED-Ed, August 16, 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgrwWuaRuso.

[29] Anderson, Laurie Halse: Chains (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2008); Ashes (New York, NY: Atheneum, 2016); Forge, (New York, NY: Atheneum, 2010).

[30] Anderson, M. T.: The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation: Volume 1 – The Pox Party (Cambridge, MA: Candlewick, 2006); The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation: Volume II – The Kingdom on the Waves (Cambridge, MA: Candlewick, 2008).

2 Comments

For more detailed information on the subject see:

List 13. African Americans Serving in the Armies of the Revolution

https://www.academia.edu/42861654/African_Americans_Serving_in_the_Armies_of_the_Revolution

And:

“You never see a regiment in which there are not a lot of negroes”: An Overview of African Americans in the Continental Army and Comparison to Black Soldiers with British and Loyalist Forces

https://www.academia.edu/129467933/_Many_of_them_have_Proved_themselves_brave_An_Overview_of_African_Americans_in_the_Continental_Army_and_Comparison_with_Black_Americans_with_British_and_Loyalist_Forces

Contents

1. “Expressly forbid enlisting any Boys – Old Men – or Slaves”: Black Men in Continental Regiments

2. “To be Sold at Public Vendue”: Two European Armies and the Institution of Slavery

3. “All Negroes, Molattoes, … who have been admitted into these Corps be immediately discharged”:

British and Loyalist Corps’ Limited Use of Black Soldiers

Ten Facts: Black Patriots in the American Revolution

https://www.academia.edu/76438882/Ten_Facts_about_Black_Patriots_in_the_American_Revolution or https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-black-patriots-american-revolution