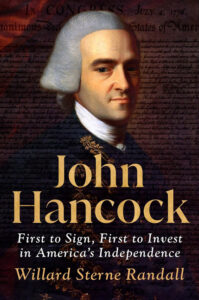

BOOK REVIEW: John Hancock: First to Sign, First to Invest in America’s Independence by Willard Sterne Randall (Dutton, 2025).

Trends of historical research over the past few decades have steadily moved away from the “Great Man” study of the past that produced a slew of works on singular characters of important periods in favor of an approach that focuses on the periphery of societies. Still, from the amount of biographies and character studies released in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it will probably come as a surprise to the reader that a name as famous in the founding mythology of the United States as John Hancock would be largely ignored. This work, John Hancock: First to Sign, First to Invest in America’s Independence, is noted biographer Willard Sterne Randall’s attempt to remedy this omission.

The early twentieth century saw the rise of an economic interpretation of the American Revolution popularized by Charles Beard; caught up in that generalized dismissal of the elite leaders of the Revolutionary movement was Hancock. Randall points out instances such as a scathing piece in the Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1930 that excoriated the Boston merchant, reducing him to his wealth and his well-known gout, a secondary indication of his social status as one of the colonies’ richest men. Hancock has long been notable as one of the most understudied figures among the founding fathers, something that has only been partially remedied in the past few decades with works such as Harlow Unger’s John Hancock: Merchant King (2000) and most recently Brooke Barbier’s King Hancock (2023). Still, despite receiving more attention than in previous decades of scholarship, the prevailing view of Hancock remained that of a foppish dandy rather than a foundational figure of the Revolution.

The early twentieth century saw the rise of an economic interpretation of the American Revolution popularized by Charles Beard; caught up in that generalized dismissal of the elite leaders of the Revolutionary movement was Hancock. Randall points out instances such as a scathing piece in the Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1930 that excoriated the Boston merchant, reducing him to his wealth and his well-known gout, a secondary indication of his social status as one of the colonies’ richest men. Hancock has long been notable as one of the most understudied figures among the founding fathers, something that has only been partially remedied in the past few decades with works such as Harlow Unger’s John Hancock: Merchant King (2000) and most recently Brooke Barbier’s King Hancock (2023). Still, despite receiving more attention than in previous decades of scholarship, the prevailing view of Hancock remained that of a foppish dandy rather than a foundational figure of the Revolution.

One reason for this lack of representation is the relative lack of documentation for Hancock’s early and more personal life, particularly when compared to the wealth of sources available for the top tier of founding figures such as John Adams or George Washington. Randall also points out that previous biographers had overly relied on the writings of the wealthy Bostonian’s political enemies. Working under some of the constraints of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, Randall relied on much of the recently digitized archival material that has gone so far in democratizing the research and writing process. These research limits do, however, noticeably impact the depth and length of this work; it comes in at only 288 pages in its printed version, short for a full-length biography and short by the standards of Randall when compared to his popular works on other founding figures.

This brevity is most apparent in the opening section covering Hancock’s early life. Only three short chapters cover his days before taking over a prominent trading house from his extremely wealthy uncle. The heady days of growing discontent and revolutionary rhetoric of the 1760s are addressed in Chapters 4 through 6 before getting into the meat of any discussion on Hancock, which must include his role as a rebel leader and time as president of the Second Continental Congress, covered in Chapters 7 through 13. The work finishes out with a brief overview of Hancock’s role as the first governor of Massachusetts and his political work in trying to set precedents for democratically-elected government in his home state.

In John Hancock: First to Sign, First to Invest in America’s Independence readers will get an easily digestible reassessment of the contributions of a man often overlooked in the story of how the United States came to be. What the reader will not get is a deeply detailed look into the private life of Hancock or a highly nuanced interpretation of his life and times. Notably for any work produced in the last several decades, Randall does not attempt to investigate the relationship of the Hancocks with the institution of slavery.

He also presents an image of the loud, early supporter of a break with Britain which contrasts with the more consensus view that Hancock was a moderate who was happy to profit from his relationship with the mother country until the various crises of the 1760s impacted his personal economy, and who often vacillated between the two points until relatively late in the game, at least when compared to radicals like Samuel Adams. At times the tone of this work can verge on the hagiographical, harkening back to an era of American biographies that contributed to the mythologizing of the founding era. The most apparent example of this is the uncritical presentation of Hancock’s well-known generosity as simple philanthropy rather than as a likely well-considered political tool.

Yet, even with these limitations, Randall’s biography succeeds in one crucial respect: it places John Hancock back into the core of the Revolutionary story, not as a footnote with a flamboyant signature, but as a consequential actor whose wealth, charisma, and political maneuvering deserve renewed attention. As a merchant, Hancock was integral to the economy of America’s most important port city, and as a politician he guided a fractured colonial legislative body toward a final break with Great Britain and molded the political atmosphere of Massachusetts in its earliest years. When revolutionary principles seemed to be dying in the post-war years leading to one of the first major challenges to newly established government in Shay’s Rebellion, Hancock was the man, sick and beaten down from a lifelong battle with gout, who returned to executive office as the only political figure with enough popularity to bring his state back together.

In that sense, this biography is not just a study of Hancock – it is a reminder of how easily history can overlook even the most visible figures. While this may not be the definitive work on Hancock’s life, it still has incredible value as an accessible and much-needed entry point into the life of a critical founding figure often reduced to a signature. As a narrative, this is an important gateway for readers into Revolutionary-era scholarship.

PLEASE CONSIDER PURCHASING THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON IN HARDCOVER OR KINDLE.

(As an Amazon Associate, JAR earns from qualifying purchases. This helps toward providing our content free of charge.)

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...