BOOK REVIEW: The Fate of the Day: The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780 by Rick Atkinson (Crown, 2025) $42.00 Hardcover

The revolt that led to the loss of its thirteen Atlantic coast colonies was one of the slowest moving train wrecks in the storied history of the British Empire. Beginning as early as 1761 with the use of writs of assistance to enforce an increasingly onerous trade and customs regime, the coming decades would witness numerous missteps dramatically altering global map lines. In his latest work, The Fate of the Day, journalist turned military historian Rick Atkinson continues his detailed narrative of the American Revolution, covering the period from 1777 to 1780 in which it spiraled from colonial scrape to global conflict.

Like the first volume of his projected trilogy, The British Are Coming, this new work is primarily a military history of the conflict told with great attention to detail and lucid (and lurid) accounts of battles large and small. Saratoga, Bennington, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Charleston receive thorough coverage, but battles such as Hubbardton, Oriskany, Paoli, Newport, and Stony Point receive a few pages as well. As with its predecessor, Fate of the Day contains those intimate details of conflicts that provide the reader a keen sense of the chaos and terror with which eighteenth-century battles were conducted. Combatants often lacked a clear sense of the local geography and faced a disturbing lack of uniformity in battle dress between Continentals, militia, irregular forces, and a multitude of Hessians that made friendly fire a constant danger.

Like the first volume of his projected trilogy, The British Are Coming, this new work is primarily a military history of the conflict told with great attention to detail and lucid (and lurid) accounts of battles large and small. Saratoga, Bennington, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Charleston receive thorough coverage, but battles such as Hubbardton, Oriskany, Paoli, Newport, and Stony Point receive a few pages as well. As with its predecessor, Fate of the Day contains those intimate details of conflicts that provide the reader a keen sense of the chaos and terror with which eighteenth-century battles were conducted. Combatants often lacked a clear sense of the local geography and faced a disturbing lack of uniformity in battle dress between Continentals, militia, irregular forces, and a multitude of Hessians that made friendly fire a constant danger.

Atkinson expands his field of coverage in this second volume to include the French court as Europeans became increasingly aware that what was going on across the vast Atlantic was not merely some small brushfire. Individuals, such as the Marquis de Lafayette and “Baron” Friedrich von Steuben, and European monarchs alike viewed the conflict as creating new possibilities personally and politically. Appropriately, Atkinson sets his prologue in Paris and provides a greater range of diplomatic history throughout in this volume.

Back in North America, the narrative commences with what Atkinson terms the “March of Annihilation,” Gen. John Burgoyne’s ill-fated invasion from Canada to meet up with Gen. William Howe’s army, thereby cutting New England off from the rest of the colonies. The focus of much of the first third of the book, that campaign (which Howe’s successor would rue as “the height of impropriety and bad policy”) would ultimately lead to the French alliance and eventual appearance of their troops, and even more importantly their naval forces in American waters.

By 1777, the British were knee deep in North America. A third of their naval and fully one half of their land forces were fighting there. Additional troops were hired from German principalities. This growing strain was creating serious political unrest back home in England. We see the English opposition increasingly rising up against what it viewed as the government’s policy of solving a political problem with the use of military force. As the North ministry doubled down on coercion, William Pitt the Elder, the great hero of Seven Years War, rallied those who viewed the American cause sympathetically, prophetically warning that efforts to subdue America by force were doomed to failure:

You cannot conquer America . . . Your efforts are forever vain and impotent . . . If I were an American, as I am an Englishman, while a foreign troop was landed in my country I never would lay down my arms. Never, never, never!

During this period of the war, command of British armies transitioned from Howe to Henry Clinton. Howe captured New York and Philadelphia, and triumphed in multiple battles with the American army such as Brandywine and Germantown. Yet it was this Philadelphia campaign that left Burgoyne exposed in the Hudson Valley, and Howe’s failure to deliver a decisive blow led to his recall in February 1778.

Valley Forge proved transformational to the American Army in several respects, and Atkinson touches upon the story of how the arrival of von Steuben led to dramatic improvements in its effectiveness as a fighting force. This is one of the few military aspects of the story that could have benefitted from greater attention, as von Steuben’s efforts would show themselves as the snow and ice thawed in the spring of 1778.

In June at Monmouth Courthouse, Washington’s revitalized army finally matched the British and credibly claimed victory when the Recoats chose to vacate the field and continue their march to New York rather than chance the knockout encounter that had one time been at the heart of British strategy. Having faced a more professional American army at Monmouth, Clinton would constantly overestimate American strength, and stay largely bottled up in New York as the expansion of the war led the British government to fear for the safety of its Caribbean empire and require what resources he could spare be sent there rather than focusing on Washington. Coastal raids and eventually a Southern strategy would emerge as the new British gambit.

In his account of Monmouth, Atkinson shows a great deal of sympathy for Charles Lee, to whom history (not to mention Broadway musicals) has not always been kind. Washington’s less-than-precise orders left Lee with enough latitude to justify his decision not to press harder, in Atkinson’s judgment. Insolence, not disobedience, was Lee’s real fault and it was his insistence on a public trial that would force the Board of War to choose between him and Washington that ultimately doomed him. At the end of the day, however, rehabilitating the eccentric Lee seems a chore. His personality did not serve him as Washington’s subordinate, and his service would not be missed.

While the conflict on land dominates Atkinson’s accounts, the navies are not neglected. As Fate of the Day opens, almost all the naval firepower, aside from smaller coastal ships and some raiders under John Paul Jones and others, belonged to the British. Their ability to move troops by sea frustrated Washington, who could only guess at where they might land. Atkinson profiles the British admirals, particularly Richard “Black Dick” Howe, whose brother commanded on land, in depth. One of the great questions is what might have occurred at the Battle of the Capes (and hence Yorktown) had Black Dick not decided that he had had enough and returned to England in September of 1778.

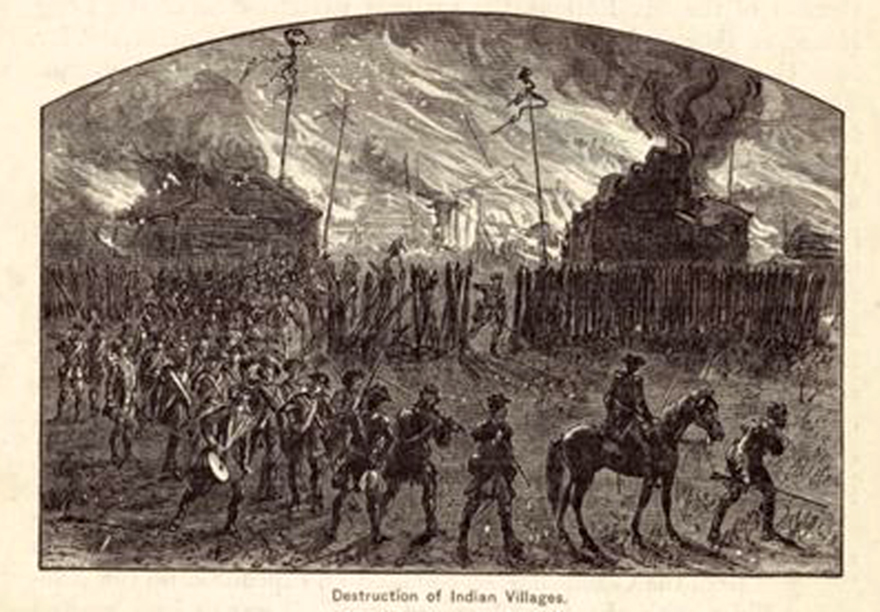

The role of native Americans also features larger in this new volume. At the outset of the war, Congress had sought their neutrality, but British advantages in material goods and the constant westward push of white settlements led the bulk of natives to side with the British forces. Atkinson does not focus sustained attention on the war’s impact on native populations. They are mostly present as allies or hated enemies. Fierce warriors, they could also be hard to control, and atrocities committed by and against them are increasingly part of the narrative as the war drags on. Atkinson includes Franklin’s acknowledgment that “almost every conflict between Indians and whites was ‘occasioned by some injury of the latter towards the former.’”

Although he leaves off in North America with what is perhaps the high point in the conflict for the British, the seizure of Charleston, all was not well at home. In the epilogue, Atkinson provides a rich account of the Gordon Riots, and astutely notes that King George III’s resolute use of force would turn a horrific event into support for the government’s use of force overseas as well. Despite suffering an estimate 26,000 casualties to date, support for continued war in America continued to prevail over the growing opposition of Pitt, Edmund Burke, and others. Meanwhile, more and more Americans, steeled by war’s hardships, were beginning to see America as their country, and Congress as their government, as the future Chief Justice John Marshall would write.

Atkinson is the latest in a tradition of journalists turned serious historians, such as Douglas Southall Freeman and Allan Nevins. Given the depth of research, deliberation in judgment, and painstaking attention to crafting a compelling, clear narrative, this volume is worth reading with the same care as it was written, as we are likely to have another lengthy period before seeing the final volume.

2 Comments

A very informed and thought-provoking review. My wife and I had the pleasure of attending Atkinson’s talk and book signing at Mt. Vernon last week. His talk and your review whet the appetite for “getting on” with digging in to his latest volume. Atkinson is a keen student of military history. Above all, he is such a fine writer.

It is well written. No question it is a good read., and is (seemingly) well researched, but it uses a lot of modern sources. The familiar myth that Horatio Gates looked older than he was, had stooped shoulders, wore his glasses perched at the end of his nose, and was called “Granny” is a prime example. I debunked this often repeated trope in JAR eleven years ago.