“I am drove almost to death for money. We are rich poor cursed rascals. By God, alter our measures or we shall be a hiss, a proverb, and a bye word, and derision upon earth.” Ethan Allen writing to Ira Allen, August 18, 1786.[1]

How could two renowned, high-ranking men from Vermont’s Revolutionary period, the brothers Ethan (1738-1789) and Ira (1751-1814) Allen, have fallen into such dire straits in the nation’s early years that they feared the loss of all they worked for? Unsurprisingly, revolutions inevitably serve up unexpected consequences and the hard times the two men faced in the period between war’s end and the War of 1812 vividly proves that hard truth.

For the historian removed by more than two centuries attempting to unravel the circumstances of their distress, and that of others swept up in their charisma, requires some effort. It is a complicated story, but is one that shines through when the approximately 150 lawsuits in which they are named, one including a future president of the United States, are examined.[2] (You can see a list of lawsuits here.) While there are shadowy other suits lurking in the background, extant records comfortably reveal at least this extraordinary number and the huge financial stakes they posed.[3]

Before the lawsuits began, the frontier the Allens occupied offered an abundance of opportunities to the resourceful entrepreneur. Their early exploits involved removing themselves from Connecticut northwards to thwart the opposing claims of New York and New Hampshire governments to this terrain that later became Vermont in 1791. Flexing their unhindered control, together with brothers Heman and Zimri and cousin Remember Baker, the five formed the Onion River Land Company (ORLC) in 1774. When Ethan led the attack on Fort Ticonderoga on the New York side of Lake Champlain the following year, the family claimed ownership of 65,000 acres of northern Vermont land forming the basis of their wealth. Building on an ethos of swindling and fraud, he and Ira distinguished themselves both before and during the war, selling off as much as they could, lining their pockets as quickly as possible.[4]

Unfortunately, the victims of the brothers’ shady operation, and assorted business associates, occasionally resorted to filing lawsuits trying to claw back the money they paid. Inevitably, they found themselves unable to obtain any recourse because of the brothers’ inability and/or unwillingness to disgorge their ill-gotten gains. Their command in running a loose frontier government and its important land granting and recording processes allowed them to both profit from the inherent disorder and to put a spin on unfavorable circumstances when challenged.[5] This assured them that their cherished reputations remained intact and kept their losses to a minimum. However, that dream of financial reward began to unravel, faltering in the same way that Samuel Taylor Coleridge gave voice to in his Rime of the Ancient Mariner: “Water, water everywhere nor any drop to drink,”[6] the equivalent of Ethan’s lament to Ira in 1786 that “we are [land] rich [money] poor rascals.”

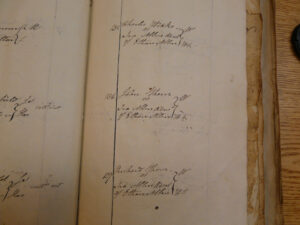

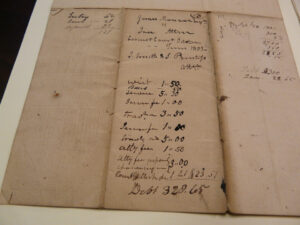

The many extant court documents demonstrating the truth behind Ethan’s observation from this time forward exposes their stumbles on dozens of occasions. It constitutes a rich resource of previously untapped information about the brothers, allowing reconstruction of some lesser-known aspects of their dealings. Frustratingly, those records are not complete. But they do, at least, show the nature of the disputes they were involved in unfolding in state and federal courts, the names of the parties and their attorneys, relevant dates, and a maze of final dispositions. Delving into the dusty, dirty docket and record books, and the case files, and interpreting the cryptic, abbreviated entries made by clerks (one admitting in a case that important papers had been “lost or mislaid”[7]), make reconstructing these dynamic courtroom moments a constant challenge. Nonetheless, they do identify an evolution of the law taking place with its increasing sophistication after the war. This includes the financial aspects underlying the brothers’ transactions when the traditional British pound-shilling-pence monetary valuations yielded to the implementation of dollars and cents after passage of the Coinage Act of 1792; as well as experimental ways to resolve disputes (i.e., the short-lived Bankruptcy Act of 1800).

Ethan Allen

At six feet, two inches tall, the 220-pound Ethan Allen towered over his brother, Ira, thirteen years younger, standing at five feet, seven and one-half inches, and possessed of a slender, wiry frame earning him the nickname of “Stub.”[8] The eldest of six brothers, Ethan exemplified what it took to establish and maintain a no-nonsense frontier reputation. In the realm of his financial affairs when repaying a debt, he wore a public mask of a benevolent benefactor graciously bestowing money to a creditor not out of a sense of obligation, but because it was, for him, “honorable” to do so.[9] Ethan successfully spun that reputation so well during his lifetime that one of Ira’s associates reminded him after his brother’s death in 1789 that “though possessing many eccentricities, peculiar to himself, [he] exhibited, through life, a strong sense of honor, and an invincible spirit of patriotism.”[10] Notwithstanding, the façade that Ethan sought to portray cracks deeply when the period court documents are examined. Notably, they demonstrate that the hero of Fort Ticonderoga left behind a legacy of at least twelve frustrated creditors making claims against his estate of over £407 and $1,714.

Aside from the land sales Ethan participated in with the ORLC in the pre-war years, the first financial transactions he engaged in resulting in posthumous lawsuits took place in 1777 on New York’s Long Island. Never before disclosed, we now know that they occurred while he was in British custody but free on parole following his capture early in the war. Three claimants (Charles Hicks, John Thorn, Richard Thorn) filed their lawsuits in a Vermont court over a decade later in 1793, years after Ethan’s death, each naming Ira as the defendant in his role as administrator of Ethan’s estate.[11] The men alleged that on August 20, 1777, they had met with Ethan for an unstated reason, perhaps related to his need for money to pay providers of his shelter and food. It could have also been connected to the war in some fashion because claimant Thorn held the position of major in the local rebel militia.

In exchange for Ethan’s signing three documents (“commonly called a promissory note,” the suits record) agreeing to repay money in three months’ time, they each provided him with £15. Apparently, his captors became aware of the transactions when, five days later, on August 25, they canceled his parole, placing him back into custody. Never referring to his meeting or existence of the loans, the closest Ethan ever came to explaining the reason behind the revocation was that it was done “under pretext of artful, mean and pitiful pretences, that I had infringed on my parole.”[12]

In the early stages of the ensuing lawsuits for Ethan’s notes, Ira received legal assistance from a recent Yale graduate, twenty-three-year-old attorney and Burlington postmaster John Fay; he would continue to represent Ira in other cases in the next years. The matters received numerous continuances in the courts between 1793 and September 1795 when each went into default resulting in awards to the plaintiffs of over £95. The defaults were attributed directly to Ira’s apparent disdain for the proceedings because, as occurred in dozens of other suits, he simply chose not to attend; neither do the papers indicate that Fay attended. As with so many of the plaintiffs in their suits involving Ira, the three plaintiffs’ success proved a Pyrrhic victory. When sheriffs repeatedly tried to collect the amounts owed from him, Ira said he had spent all of Ethan’s estate on his surviving relatives, leaving the plaintiffs to console themselves with filing meaningless attachments on his property.

In other litigation involving Ethan, two years after receiving the Long Island loans, his first documented foray into the legal world as a named litigant occurred in Bennington in December 1779. There, he and Ira joined together to bring suit against their brother Levi, in the matter of General Ethan Allen & Ira Allen versus Levi Allen. The claim concerned Levi’s failure to convey certain rights to land in St. Albans to his brothers in breach of a pre-existing agreement to do so. After receiving evidence, the court found for the plaintiffs, ordering that Levi convey the land as he had promised.

To assure their survival in these times, Ethan and Ira became masters at manipulating the legal system. Ethan’s boldness in challenging Levi in court reflects a certain comfort level with the legal system. Earlier, in 1767, he counseled brother Heman in a lawsuit giving him specific instructions in the preparation of a legal document, an effort he repeated in 1787 when providing legal advice to Levi (after their reconciliation) in the preparation of another document.[13] It is ironic that Levi received such Janus-like treatment from Ethan as it was he his brother relied on to pay off debts out of his own pocket, for which he never received reimbursement. This later required Levi to make several claims against Ethan’s estate for sums owed which, as in virtually every matter involving the finances of Ethan and Ira Allen, he never received.

The drumbeat of Ethan’s neglect to pay his creditors dogged him after 1777. Failure to repay several other debts and notes he signed (Sam Hand, John Armstrong, Jr., Joab Stafford), his refusal to settle book accounts with a another (Alexander Frazier), his several breaches of contract (William Blodgett, Wolcott Hubbell, Chauncey Ensign), and, just six days before he died, his refusal to convey land to an attorney (Timothy Hollibert) demonstrate the diverse ways he escaped accountability for his obligations. But for his life ending when it did, there is little reason to believe that Ethan, even in the face of approaching financial collapse, would have changed the course of his questionable dealings. Only a short time after his death, Ira stepped out from under his shadow to shoulder even larger financial losses extending out over the next two decades, ones that neither of them could have ever imagined.

Ira Allen

Ira led a rich, diverse life with many highs and a crushing ending. During the war years, he: oversaw the confiscation and sale of Tory lands; acted as the government’s treasurer between 1777 and 1786 (using “sloppy” bookkeeping methods[14]); served as secretary to Gov. Thomas Chittenden; worked, as a member of the twelve-man Council; and supervised the division of land as Vermont’s first surveyor-general to a throng of hungry newcomers arriving in the 1780s and 1790s—a position allowing him to extract large sums of money from land jobbers. While other like-minded grifters pursuing dreams of profits in land elsewhere engaged in the same kind of the conduct, Ira’s slippery ways marked him as different, as one who “perfected what his less resourceful counterparts merely practiced.”[15]

The inside understanding of politics, financing, and land dealing processes that Ira gained during those experiences proved invaluable. They served him so well that by 1790 he became major-general of militia, allowing him to assume the nom-de-plume of “General Allen.” Such cumulative notoriety allowed him to claim ownership to some 120,000 acres of land located in more than fifty towns.[16] With the improvements he made (houses, barns, sawmills, gristmills, and forges), together with income from tenants, in 1793 officials estimated his total statewide worth at £100,000.[17]

Unfortunately, Ira’s inability and/or unwillingness to pay the debts he incurred along the way failed to match his land grabbing acumen. In short, Ira was not a detail man. As his legal woes began to unfold in the 1790s it became increasingly clear that many of his past land transactions were based on questionable deeds. They were ones he creatively negotiated, drafted, processed, and recorded with trusting town clerks relying on his representations for accuracy and truthfulness employing their rudimentary recordkeeping techniques, but with little oversight.

Ira’s sloppy ways had ramifications decades later when parties claiming rights to land he conveyed earlier fought in court trying to use his papers to substantiate their positions. In one instance in 1784, while acting as proprietors’ clerk for the town of Georgia, he signed a deed directing that it be recorded. It was not, remaining in his possession for over two decades until 1805 when officials stumbled upon it among his papers.[18] In 1859, one lawsuit noted that in June 1798, Burlington’s proprietors alerted the public to the messiness Ira caused with the town’s land records under his control. Allen, they wrote, “hath generally avoided mentioning the name of the original grantee in his deeds of conveyance.”[19]

Additionally, when interacting with town clerks recording his deeds, Ira proceeded in a highly suspicious manner. He refused to follow the accepted practice of leaving the original deed of land he sold with the town clerk for recording. Instead, he left them with a copy in a process so unusual that Chittenden Country Sheriff Stephen Pearl, accompanying him to Alburg sometime around 1794 to record a deed, was questioned during a lawsuit. When deposed under oath about what Ira said to Pearl about why he did not follow the normal routine, the sheriff responded that “they were such a pack of people there he dared not trust his original deeds with the town clerk.”[20] For a man so well-versed in land transactions, the shortcuts and secrecy Ira employed in his work raises the prospect of fraud. But who would dare to question General Ira Allen, a man of such high repute? He made the rules, but also abused them repeatedly with abandon, showing that he worked under a veil of unaccountability and disdain for the process.

In tandem with his land dealings, Ira’s business dealings in New England, New York, Upper Canada, England, and France allowed him to cut a wide swath unlike any other among his increasingly resentful peers. Their inevitable disputes with such an individual willing to stretch the bounds of accepted behavior covered a gamut of interests. They came to consume the time, money, and emotion of many forced to appear in Vermont’s state and federal courts to resolve their abundant souring land, business, and personal dealings.

While the surviving documentation of Ira’s lawsuits taking place after statehood in 1791 provide a general understanding of what occurred, those beforehand are cursory, delivering but little information. The names of litigants are recorded, but the substance of their claims are difficult to ascertain because of the abbreviated way that clerks recorded the courts’ business. Nonetheless, there is a story to tell from what has survived.

Family Lawsuits

While Ira came to litigate with many individuals and companies from inside and outside Vermont, his earliest cases involved his immediate family. None of it was pleasant, vis-à-vis his participation with Ethan in their suit against brother Levi in 1779. Notwithstanding, following the early deaths of all his brothers, and cousin Remember Baker, he was appointed administrator of their estates. This obligated him to take responsibility to preserve their assets, respond to creditors’ claims, and, for those matters reduced to lawsuits, appear in court to protect their interests. Inevitably, the fate of each only repeated the outcome of Ethan’s estate with Ira remaining in character, neglecting his duties, and allowing them to go into default, with some incurring significant assessments against them.

Notably, of all the lawsuits Ira experienced in his lifetime, none inflicted more monetary damage than the one involving his niece, Lucinda, resulting in a huge judgment in her favor in 1798.[21] Thanks to the legal documents describing what happened, we now know much more about it than what has been described in the past. They also provide an excellent example of how a complicated case wound its way through Vermont’s federal circuit court sitting as a court of chancery exercising equity pursuant to the recently enacted Judiciary Act of 1789.

It began in April 1778. Close to death, Lucinda’s father, Ira’s brother Heman, agreed to convey ownership to a substantial number of Burlington-area acres to Ira with his promise to place them into approximately-one-year-old Lucinda’s hands when she turned eighteen. Ira agreed to do so, signing a huge £30,000 bond (also covering his role in administering Ethan’s and Remember’s estates) to ensure it happened.

Upon Heman’s death weeks later, Ira moved quickly (as he did with the other estates) to put as much property under his control as possible. In a deposition sworn to by Heman’s wife Abigail as a part of the approaching litigation, she witnessed Ira immediately take control of “ten tuns of wheat” and “a large sum of money” she estimated at “several hundred pounds.” The next day, she was present during a conversation between Ethan and Ira when they read Heman’s will and talked about the value of the land Lucinda was to receive at her majority. “If the Country should never be made a State,” she heard Ethan say, referring to the prospect of Vermont’s statehood, he estimated the lands would be worth “fifteen thousand pounds.”[22] In response, Abigail said Ira “made no reply.” With Heman’s interests to large tracts of valuable land now under Ira’s control, and the prospect of Lucinda’s interference years away, the path opened for him to develop both those and what he owned into the vision he planned for the region.

Ira’s commingling of assets from other sources with his own, in this case as well as others in the future, without accurately documenting amounts he was legitimately responsible for on their behalf, caused considerable hardship. Notwithstanding, court documents do reveal him making two statements acknowledging his obligation to Lucinda as she was about to turn eighteen. In the fall of 1793, according to her physician, she was then in “a very deranged state of mind” when Ira came to see her. He told the doctor that “he need spare no expense to cure Lucinda” because “she was able to pay any [amount] and that she was intitled to a pretty Estate; which was in his hands.” He estimated that her land was worth “eight or ten thousand pounds,” as well as other obligations owed to her valued at “three and four thousand pounds.”[23] Ira also questioned Heman’s widow, Abigail, at the same time, asking “Should Lucinda die, what would become of her ten thousand pounds?”[24]

Lucinda survived her illness, married Burlington businessman Moses Catlin, and reached the age of majority in 1795 when she should have gained access to the property under her uncle’s control. Belying the false concern he expressed for her well being just two years earlier, Ira refused to convey those very lands. There was too much at stake for entrepreneur Ira to give up at that moment, forcing Moses Catlin to institute a lawsuit on both their behalfs which went on to affect many others besides the Catlins. This included the interests of the entire town of Colchester and forty-four Burlington landowners for the years it took to resolve their litigation when those lands were attached because of Ira’s interests in them. It was a mess for anyone to try and unravel, all attributable to Ira’s abysmal bookkeeping.

The case of Moses and Lucinda Catlin v. Ira Allen began in May 1795 in the federal circuit court sitting in Windsor. Noted attorneys Nathaniel Chipman and John Allen represented the Catlins. Ira was apparently able to muster sufficient money to pay for legal assistance in the monumental case, engaging the powerhouse team of Stephen Jacobs, Daniel Buck, and Samuel Miller to stand in for him. Chipman and Allen sought two forms of relief on Lucinda’s behalf: payment of the £30,000 bond for breaching Ira’s 1778 promise to convey the lands in issue, or their deeds. Little progress was made in the next two years as Ira’s attorneys obtained a series of continuances.

Because Ira was in England by this time and unable to personally contest the claim, judgment was rendered for the Catlins for the entire amount of the bond. Arguing against such a high award, Jacobs, representing Ira, requested that the amount be “chancered” pursuant to the Judiciary Act of 1789 authorizing chancery jurisdiction in the federal courts. The court agreed and in May 1798 reduced the amount to $46,720, the sum reflecting the time of transition between the use of pounds and dollars in the courts’ judgments. Finally, years after she should have received ownership of her departed father’s legacy, success arrived for young Lucinda, vindicating something that should never have occurred in the first place. Unfortunately, unable to recover such a large sum from the perpetually financially challenged Ira, the Catlins filed attachments on the lands in question.

As the case lingered in the courts in the summer of 1797, Ira’s brother Levi weighed in on the emotional toll inflicted on the family. Attacking Ira’s role as administrator for the various family estates, Levi quipped that:

Ira always came in when life was done

To see what worldly goods remain

To which my feelings ne’er could bend

Ira – the executor to what remained.[25]

But many others outside of the family also awaited their turn to experience the pitfalls of dealing with Ira Allen.

More Lawsuits

The tenor of Ira’s lawsuits changed markedly in 1795 after the Catlins filed their complaint and when he absented himself from the state in October and headed for Europe. In the few years beforehand, the monetary stakes behind Ira’s legal troubles were comparatively benign. When he appeared as a plaintiff (30 percent of the time), the issues ranged from seeking the repayment of a small loan to gaining compensation from individuals for damage inflicted to walnut trees. The scant successes he gained in these few matters appear more as petty harassment against his enemies than of any substance. In other cases when he was scheduled to prosecute his grievances, the records repeatedly note his failure to attend the proceedings.

When named as a defendant, the stakes were markedly different. At the same time the Catlins filed their suit, records reveal Ira conceding substantial amounts of money to out-of-state business associates; a pattern he followed in the time leading to his final flight from the state in 1803. Four New York City merchant and trading companies successfully pressed their cases against him, arguing that despite signing promissory notes to pay amounts owed for the goods they sold, he refused to do so. His powerful attorneys, Stephen Jacobs and Daniel Buck, recognized the futility of contesting the claims (as they would in the upcoming Catlin matter) and agreed to the imposition of some £157 and $28,186 in judgments.[26]

Perpetually land rich while monetarily destitute, Ira became desperate to find ways to keep his north country enterprises afloat. He envisioned the creation of a canal in Upper Quebec bypassing the rapids on the Richelieu River that hindered the transport of goods and passengers between Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River. If he could obtain the financial backing of the British government for such a huge project, then perhaps his problems would disappear.

But before heading for England in October 1795, Ira’s remaining cases for the September 1795 terms of the courts demonstrate his complete lack of interest to engage any further with anyone suing him. In some ten cases naming him individually for relatively small sums of money (including his failure to deliver cattle to two claimants who previously paid him) and as administrator of Ethan’s estate, he simply failed to attend the proceedings. Even a third complaint he instituted against a man for the destruction of walnut trees ended with his not appearing. As the clerk’s entries repeatedly describe, when the court was ready to hear his cases and the bailiff was ordered to summon the parties forward from the throng of people in the courtroom, “the [defendant] being three times called doth not come.” Ensuing default entries littered the records thereafter, followed by abbreviated “non-est” (short for non-est inventus) entries, meaning that the sheriff was unable to find Ira to lodge judgments against him.

With great relief, Ira departed Vermont, mentally and physically exhausted, for Boston to prepare for his European adventures. But not before ridding himself of those making his life such a misery in the courts. Writing to Chittenden County sheriff Stephen Pearl (who earlier witnessed Ira’s disdain for the people of Alburg by calling them “a pack”), Ira vented with vulgarity. “I feel myself beyond the reach of my enemies, Poor D—n-d s—s,” he said, “Any statements they can Send will appear like Envy, & Calm Deliberation will yet Govern me.”[27] As always in his past, self-preservation at the expense of others while avoiding financial ruin dominated his goals. Accountability was never a part of the equation, but “Calm Deliberation” was his refuge.

To Europe and Back

Excited at the prospect of obtaining British assistance for his canal plan, Ira only met with cold disdain. His disagreeable reputation, association with shady characters, and questionable business practices preceded him, marking him as someone no one of repute cared to work with. Bent on revenge, and with France roiled in revolutionary turmoil, he made the short trip across the Channel seeking to engage that government in an outrageous plan. Now, he proposed the complete removal of a British presence in North America, replaced by an entirely new entity called “United Columbia.” Seeing an opportunity to foil its arch enemy, the French government engaged with Ira in an ambitious plan to ship 20,000 muskets to North America for use in an attack. However, the plan soon collapsed with their seizure at sea by a British ship. In the end, Ira found himself thrown into a French jail where he languished until his release in September 1799.[28]

Following his return to America in 1801, Ira continued to try and profit from the failed musket adventure. After convincing a British court to release a portion of the weapons and having them shipped to New York, he sought to exploit discord in the southern states. This latest plan envisioned the sale of weapons to, among others, the State of Virginia, where he went to meet with Gov. James Monroe. Monroe received Ira’s proposal favorably, but remained uncommitted until the muskets were examined by an associate. In the meantime, to assure Ira’s good faith, Monroe wisely insisted he sign a $600 bond promising to pay $300 to compensate the associate for his troubles. On March 28, 1801, Allen agreed and signed the bond.

As with so many of Ira’s escapades, this effort went awry, forcing Monroe to file a lawsuit against him in Vermont’s federal court seeking the $600 bond, as well as $1,000 in damages. In May 1803, the future president succeeded in his claim and obtained a judgment in his favor in the amount of $600. As Ira did previously in the matter involving his niece, Lucinda Catlin, he sought and obtained relief from the court, which exercised its “chancery” jurisdiction and reduced the fine to $300, plus $28.65 in costs.[29]

It was not often that Ira ever received a favorable result from the courts, such as what he experienced in Lucinda’s and Monroe’s cases. His physical absence between 1796 and 1801 did nothing to stop dozens of others from filing their own grievances in the courts seeking redress. They ranged from debt and note obligations, payment of taxes, seeking compensation for services rendered, settling amounts owed on book accounts, breach of contract, and the sale of livestock. Even his own attorneys, Elnathan Keyes and William Harrington, received similar treatment from their client, forcing them to file their own suits for payment of over $2,000 in legal fees. As usual, they received nothing in return, with Keyes only able to attach 10,000 acres of Ira’s Caledonia County land.[30]

None of these suits was a surprise to Ira because family members wrote to him in Europe many times explaining his dire legal situation at home. Tone deaf to their warnings, he continued to believe in his self-importance and called on the courts to delay the cases. He contended that his time spent in Britain and France constituted “sufficient grounds for continuing all suits against me till I can have an opportunity to answer in my own defence.” Ending, he demanded that “I therefore expect justice in the State of Vermont.”[31] Alas, the uncertainty of when he would, if ever, return to Vermont, coupled with the widespread harm he imposed on his neighbors, prompted immediate court attention as the judgments continued to mount up against him.

Flight and Bankruptcy

By 1803 Ira stood alone, virtually friendless, facing a deluge of adverse judgments. A recent ruling that he owed more than $69,823.36 to brother Ethan’s heirs struck hard, convincing him to get his affairs in order before fleeing. With the assistance of confidants, he stole away in the dark, sailing south on Lake Champlain to Ft. Ticonderoga. Remaining steadfast to avoid accountability for his obligations, he headed to Kentucky with another plan to remove the stain of debt from his reputation.

In 1800, Congress passed a short-lived law affording relief to debtors, entitled An Act to establish an uniform System of Bankruptcy throughout the United States. One provision allowed for the discharge of a debtor’s obligations if a creditor who was owed more than $50 filed a petition with the court saying he was the only individual with such a claim and that he would not contest entry of a decree of bankruptcy. Ira was able to obtain the assistance of former Vermonter Matthew Lyon, recently elected by Kentucky to the U.S. House of Representatives, to act as a purported creditor making the necessary, but bogus, claim. The scam worked, and Ira (now passing himself off as a Kentucky resident) received the sought-after decree from the court that he was a bankrupt, thereby wiping out his debts. With similar abuses taking place elsewhere and recognizing the inherent weakness of such a process, just two months later Congress repealed the law.[32]

Appearances proved deceptive as the declaration Ira received failed to keep the wolf from his door. Returning to Vermont once he peddled himself as destitute, but nobody was buying it and the suits kept coming. Ira then made his final split from his beloved homeland and left for Philadelphia. Struggling to survive, he entered into an unwise agreement in March 1806 with Isaac Scott, an associate he dealt with when he was in England. It concerned an unidentified promise Ira made, guaranteed by a bond he signed obligating him to pay $32,072.90 if he did not perform. That result inevitably happened and Scott instituted a suit against him in a Vermont federal court seeking payment of the bond. Ira had no real defense to Scott’s claim other than to argue that he could not be sued in a Vermont court because he was not a resident of the state. The issue was ultimately resolved when a jury determined otherwise, finding that Ira “was an inhabitant of the State of Vermont.” When he failed to appear for a subsequent hearing, a default judgment against him sought entire amount.[33]

Ira continued to eke out an existence in Philadelphia until he died in 1814, finally laid to rest in a pauper’s grave.

Conclusion

Ethan and Ira Allen rode on the coattails of the American Revolution, attending to wartime needs while also pursuing their voracious land-grabbing instincts. Cut from the same cloth, the two shared many of the same characteristics: instinctively self-centered, self-important, and impulsive in their relationships with others on whom they unapologetically exercised their sharp-elbowed, me-first ways. Some saw through it, steering away, while others became enraptured, trusting in their dynamic reputations and promises convincing them to enter into financial relationships that many regretted. Ethan and Ira were not evil men, but products of their times. The persistent threat of insolvency hanging over their heads throughout their lifetimes made them outliers, ones loose with the truth and willing to indulge in swindling the unwary when necessary.

Notwithstanding, the historiography surrounding the two men has been kind and largely forgiving, allowing them to maintain their outsized reputations for over two centuries. History’s failure to acknowledge the many harmed by them only further demonstrates the indifference the two shared for those they victimized. It is a concern that deserves attention. Those family members, farmers, business associates, attorneys, and others suffering losses because of them, counting in the millions of dollars, are voices too long ignored. Thankfully, the court records can now speak for them and allow the record to be set aright.

[1] Ethan Allen to Ira Allen, August 18, 1786, Allen Family Papers (AFP), mss-062, University of Vermont Silver Special Collections, Burlington, VT.

[2] Specific amounts of money reported herein are from period documents that variously use both pound-shilling-pence and dollars-cents sums. The overall amount of all lawsuits can be interpreted as a modern day grand total exceeding $4,000,000. For further information see: www.measuringworth.com/calculators/exchange/. Thanks to JAR contributor Robert Wright for his assistance valuing early American currency.

[3] RG 21, Vermont U.S. District/Circuit Courts, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Waltham, MA; PRA-01043, Vermont State Archives and Records Administration (VSARA), Middlesex, VT; AFP. See also, J. Kevin Graffagnino, Ira Allen: A Biography (Barre: Vermont Historical Society, 2024), passim.

[4] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 25-27.

[5] For more on the Allens’ manipulation of warranty and quitclaim deeds, see Gary G. Shattuck, “’A Heathenish Delusion’: The Symbolic 1777 Constitution of Vermont,” Master’s Thesis. American Military University, 2016.

[6] William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems (London: 1798).

[7] Thomas Brush v. Ira Allen, VSARA.

[8] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 19.

[9] Ethan Allen to Levi Allen, January 29, 1787; “Levi Allen’s Acct. Current with Genl Allen deceased,” August 28, 179?, AFP.

[10] Sentinel and Democrat, April 15, 1802; Glenn Fay, Jr., Ambition: The Remarkable Family of Ethan Allen (Burlington, VT: Onion River Press, 2024), 127.

[11] Charles Hicks, John Thorn, Richard Thorn v. Ira Allen, Admin. of Estate of Ethan Allen Estate, VSARA.

[12] Ethan Allen, A Narrative of Col. Ethan Allen’s Captivity (Walpole: Thomas & Thomas, 1807), 126.

[13] Ethan Allen to Heman Allen and Ethan Allen to Levi Allen, AFP.

[14] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 70.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid., 129.

[17] James Benjamin Wilbur, Ira Allen: Founder of Vermont, vol. 2 (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928), 53.

[18] Brush v. Cook in William Brayton, Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the State of Vermont (Middlebury, VT: Copeland and Allen, 1819), 87.

[19] Townsend v. Administrator of Estate of Downer, 32 VT. 183 (1859).

[20] Deposition of Stephen Pearl, April 13, 1807, NARA.

[21] Moses and Lucinda Catlin v. Ira Allen, NARA, VSARA.

[22] Deposition of Abigail Wadhams, September 20, 1797, NARA.

[23] Deposition of Daniel Sheldon, September 22, 1797. NARA.

[24] Deposition of Abigail Wadhams.

[25] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 281.

[26] Minturn & Champlain, Broome & Platt, Caleb & Frost and James Seaman v. Ira Allen, NARA, VSARA.

[27] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 166.

[28] Ibid., 174-190.

[29] James Monroe, Esq. vs. Ira Allen, NARA.

[30] Elnathan Keyes v. Ira Allen, AFP and William Harrington v. Ira Allen, VSARA.

[31] Wilbur, Ira Allen, vol. 2, 312.

[32] Graffagnino, Ira Allen, 204-205.

[33] Isaac Scott v. Ira Allen, NARA.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...