Among the foreign-born leaders who played crucial roles in the American Revolution, Hungarian-born Colonel Commandant Michael Kovats de Fabriczy stands out for his significant, yet often overlooked, contributions to the Continental Army.[1] Kovats played a key role in the establishment and development of the cavalry, overseeing the recruitment, training, and organization of regular cavalry units. His efforts helped transform an underdeveloped force into a formidable military asset, earning recognition from a British contemporary who described his cavalry as “the best the rebels ever had.”[2] The tricentennial of Kovats’ birth celebrated in Hungary and the United States in 2024 provides a unique opportunity to highlight his influence on the evolution of U.S. cavalry and his lasting impact on American military history.[3]

Hungarian Roots, Habsburg Service, American Inspiration

Michael Kovats de Fabriczy (also written as “Kowatz,” “de Kovats” in English, and “Fabriczy Kováts Mihály”) was born in 1724 into a noble family in the Protestant town of Karcag in the Kingdom of Hungary. He led a distinguished military career that spanned much of eighteenth-century Europe. At the age of sixteen, Kovats, highly educated and driven by a sense of adventure, joined a Hungarian Hussar regiment within the Habsburg Empire’s military.[4] Seeking further opportunities for advancement, he quickly rose through the ranks, serving in both the French Bercsényi Hussar Regiment and the Prussian Székely Hussar Regiment. Over the course of thirty years, Kovats participated in several major European conflicts, including the Austrian War of Succession, the Seven Years’ War, and, later, supporting the cause of Polish independence fighting for the Bar Confederation.

In the autumn of 1776, Kovats embarked on the final chapter of his military career, volunteering to support the American cause in the War of Independence. From 1773 onward, the Pressburger Zeitung, a weekly newspaper in the Kingdom of Hungary, provided extensive coverage of the American Revolution, publishing more than 100 articles detailing the conflict between the British redcoats and the Continental Army. These reports spanned the entire course of the war, from its outbreak to the conclusion of the revolution and inspired many across the Habsburg Empire, including Kováts.

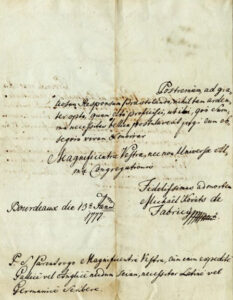

In 1777, Kováts traveled from the Habsburg Empire to Bordeaux, France, where he wrote a letter in excellent Latin to Benjamin Franklin, the American envoy to France. In the letter, Kovats modestly outlined his military achievements, emphasizing that his rise through the ranks was a result of his own efforts, discipline, and service. He also expressed his voluntary commitment to supporting the American cause, thereby offering his talents and experience to the fledgling United States:

Honourable Sir!

Golden freedom cannot be purchased with yellow gold. Those who fought for freedom used to listen to the fathers of their homeland. I, who respectfully submit this letter to You, am a free nobleman of Hungarian nationality. Not only did I receive training in the army of the King of Prussia but I also rose from the lowest rank to the rank of Major, and not by chance but rather by my military virtues, and not by the grace of fate, but rather by the very diligent observance of service discipline. In all sorts of campaigns and among bloody perils I learned all that is especially necessary for the training of recruits.

I also learned how to arm them with weapons capable of defeating the enemy, when after much learning they become seasoned soldiers, not least, in the midst of any military development and war event, how they should defend their beloved motherland. So I came here voluntarily and of my own free will, at the cost of immeasurable travel fatigue and efforts, to sacrifice myself most faithfully in all that is expected of a decent warrior in crisis situations and in the greatest perils, at Joseph’s expense and not least for the freedom of Blessing Congregation. So I arrived here, where, with the help of Mr. Fädevill, a merchant from this city and a loyal supporter of the Assembly and the cause, I had the chance to sail on board the Catharina Froom Darmouth (sic!), of which Whippy is the captain. Therefore, I ask Your Honour to help me by equipping me with a passport and a letter of faith to Blessing Congregation as a matter of urgency. And as I am still waiting here for my companions who have not arrived bere yet, Your Honour, as a true patriot would promote the public affairs with honour if you entrusted Mr. Fädevill, or another patron of your Honour’s cause here to transport them to Blessing Congregation as soon as they arrive.

Finally, in anticipation of your favourable response, I do wish to set off as soon as possible in order to live or die in uninterrupted military service where it is most necessary Your and the entire Blessing Congregation’s most faithful until death,

Mihaly Fabricy Kováts

Bourdeaux, 13th January 1777.

Postscript: I beg Your Honour to forgive me, that since I cannot yet speak French or English perfectly, I am forced to write in Latin or German.[5]

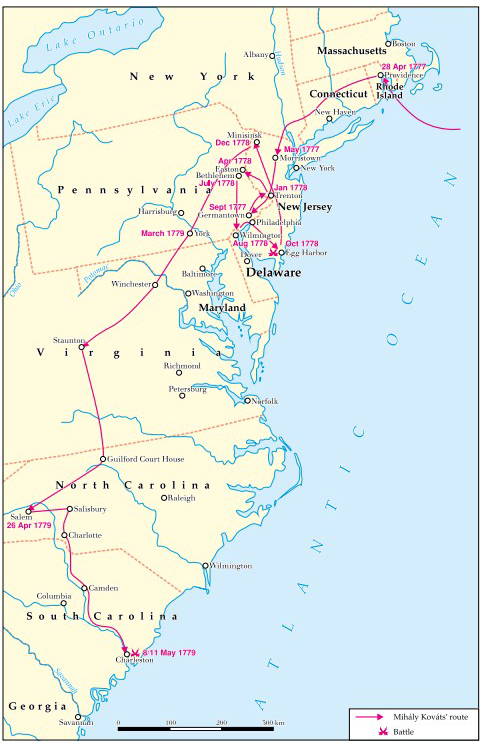

He signed his letter “fidelissimus ad mortem” or “most faithful unto death.” Less than a month after writing to Franklin, he set sail for America, arriving in the New World, in Rhode Island on February 26, 1777. Upon his arrival, Kovats was granted an audience with Gen. George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. The meeting, which took place on May 16, 1777, was hindered by communication barriers, as Kovats’ limited command of English necessitated the use of an interpreter. On May 23, 1777, the Second Continental Congress initially rejected Kovats’ offer to serve in the Continental Army, citing concerns over his language difficulties.[6]

Kovats’ resilience and keen understanding of the war soon opened up an opportunity for him. Having served in various European armies, he quickly assessed the underdeveloped state of the Continental Army, particularly in terms of equipment, organization, and composition, especially when compared to the British and European forces. Recognizing this gap, Kovats saw an opportunity to contribute his expertise in a way that could strengthen the rebel forces. His skills were soon put to use when he was appointed as a recruiting officer for the growing militias in Pennsylvania, particularly among German-speaking communities.[7] By 1777, these militias began to form free companies, which were eventually consolidated into a formal battalion. Kovats’ fluency in the German language and his experience in European military structures allowed him to play a crucial role in this development, marking a significant turning point in his military career and his contributions to the Continental Army.

Pole and Hungarian Brothers Be

Around the time that Kovats was establishing himself in the Continental Army, another prominent foreign-born figure arrived in America—Kazimierz Pułaski, a Polish nobleman and military leader.[8] Pułaski, who had previously fought alongside Kovats in the struggle for Polish sovereignty during the Bar Confederation, arrived in Boston Harbor in July 1777, on the personal recommendation of Benjamin Franklin.[9] Pułaski, like Kovats, had the opportunity to meet General Washington in August 1777. After the meeting Washington recommended Pułaski to Congress as the organizer of a cavalry regiment. This endorsement set Pułaski on a fast track to becoming one of the most prominent figures in the American cavalry.

In September 1777, at the Battle of Brandywine, Pułaski distinguished himself through his courageous actions on the battlefield. Despite a significant American defeat, Pułaski’s bravery did not go unnoticed, and soon the Continental Congress appointed him “Commander of the Cavalry, with the rank of Brigadier General.”[10]

On September 12, Col. Henry Arendt’s German Free Battalion was ordered to guard Chester, Pennsylvania, creating an opportunity for the reunion of two former European comrades—Kazimierz Pułaski and Michael Kovats—on American soil. Pułaski, a rising Polish nobleman with limited military organizational experience, would rely on Kovats’ expertise to help establish the American Light Cavalry. Kovats, at fifty-three years old and nearing retirement, found a new path into the Continental Army through his association with the ambitious thirty-year-old Pułaski. Despite their differences in age and experience, the two men’s fates quickly became intertwined.

In the months that followed, Pułaski, recognizing Kovats’ military knowledge, made him an adviser rather than a soldier, moving him out of Arendt’s Battalion. During the winter of 1777, Pułaski, energized by his new role, began submitting ideas and organizational proposals to Washington at Valley Forge. Meanwhile, Pułaski and Kovats spent the winter in Trenton, New Jersey, where they laid the groundwork for the future of the Continental Army’s cavalry.[11]

Pułaski submitted a bilingual manuscript to Washington’s high command, written in French with an English mirror translation. The manuscript, titled Memorandum relative to the cavalry, outlined Pułaski’s ideas for reorganizing and strengthening the Continental Army’s cavalry.[12] This document, which demonstrated Pułaski’s commitment to improving the American military structure, marked an important step in the development of the cavalry force, and set the stage for his collaboration with Kovats in the coming months.[13]

In the eight-page memorandum, Pulaski recommended the formation of a company of dragoons (heavy cavalry) and a company of “Bosniques” (light cavalry),[14] each with the appropriate officers and non-commissioned officers. The term “Bosniques” referred to a type of light cavalry unit known as the “Free Hussars” which had been part of the Prussian military during the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War, specifically created to counter the Russian Cossacks. Given that Pułaski had not participated in these conflicts—either by age or by birth—he had to rely on the expertise of Kovats, who had extensive experience in European cavalry units.

In another letter to Washington the same winter, Pułaski systematically outlined the organizational structure of the light cavalry regiment.[15] While it is evident that Pułaski’s manuscript covers various aspects of cavalry organization—from uniforms and the proper maintenance of saddles and bridles to the structure and composition of cavalry units—most of these ideas reflect Kovats’ nearly four decades of military experience.[16] Kovats, as an adviser to Pułaski, had a decisive influence on the Polish nobleman’s understanding of cavalry organization before Pułaski’s official appointment as colonel in 1778, highlighting the key role Kovats played in shaping the future structure of the American Light Cavalry.

Pułaski, despite his considerable military experience, had never served in the Prussian army and therefore did not have direct experience with its strict discipline or rule books. The influence of Kovats is most clearly illustrated by the fact that, beginning in January 1778, he was specifically named and commended for his contributions in the correspondence between Washington and his high command. These letters not only acknowledged Kovats’ military expertise but also marked the beginning of direct communication between Kovats and Washington, bypassing Kovats’ superior, Brigadier General Pułaski.

Kovats’ appointment as drillmaster

In early 1778, shortly after his arrival in Trenton, Pułaski recommended that Washington appoint Col. Michael Kovats as the cavalry drill master for the Continental Army. Pułaski emphasized the dire need for professional training within the cavalry and highlighted Kovats’ exceptional qualifications for the role, recommending him as an officer of great merit with a deep understanding of cavalry tactics. Pułaski assured Washington that Kovats’ expertise would be invaluable to the cavalry’s development and that appointing him would significantly enhance the mounted forces’ effectiveness during the early months of of 1778.[17]

Despite Pułaski’s strong recommendation, Washington initially hesitated to approve Kovats’ appointment, reflecting his cautious stance on placing foreigners in leadership positions within the Continental Army. Ater much deliberation, Washington granted Kovats a limited approval, appointing him as a training officer for the cavalry. This decision, though more modest than Pułaski had hoped, marked a significant step in recognizing Kovats’ value.

Kovats’ appointment as training officer and Washington’s eventual appointment of him as drillmaster can be better understood in the context of a letter written by Col. Henry Lutterloh on January 14, 1778, to Lt. Col. John Laurens.[18] Lutterloh underscored the urgent need for skilled officers to train and organize the Continental Army’s cavalry, which was still struggling with issues of discipline and proper training. Lutterloh argued that Kovats, with his experience in light cavalry, would be a more effective choice than the French officer previously considered.

To secure his appointment, Kovats took matters into his own hands. On February 4, 1778, Kovats personally wrote a letter to Washington.[19] In perfect English and extremely concisely, Kovats provided a detailed, itemized account of the cavalry equipment he had successfully purchased at favorable prices. He presented a quantitative and budgetary comparison, underscoring his own competence and expertise in managing the logistical aspects of the cavalry’s development.

Pułaski, as Kovats’ superior, continued to advocate for his advancement, emphasizing Kovats’ value to the cavalry, particularly in combat situations. Pułaski reiterated his earlier requests, including the need for Kovats to be formally appointed with authority to command a detachment, highlighting his potential to contribute significantly to the cavalry’s effectiveness in battle.[20]

By February 1778, the persistent correspondence between Pułaski and Washington suggests that the training of the cavalry had made significant progress. Pułaski’s repeated requests for Kovats’ formal appointment and his continued advocacy for Kovats’ role indicate the growing importance of resolving the matter. Pułaski’s frustrations were not limited to Kovats’ position. In his communications with Washington, the two men clashed over several key issues, including personnel decisions, recruitment, uniforms, and the cavalry’s pay scale. These disagreements gradually intensified, leading to broader tensions within Pułaski’s command by the end of February.[21]

Formation of the Pulaski Legion

With the arrival of spring in 1778, the war took on a new sense of urgency and momentum.[22] In a letter dated April 9, Washington outlined proposals for the officer corps of the “Legion” under Kazimierz Pułaski.[23] On April 18, the Congressional Committee, in conjunction with Washington, formally appointed Michael Kovats (referred to in official records as “de Kowatz”) to the rank of colonel. In addition to Kovats, Julius de Montfort, a French officer, was appointed major, and John de Zieliński was named captain.[24]

The new legion, based on the framework of the free troops originally organized by Pułaski, would later be known as the Pułaski Legion. In early April, Kovats initiated a recruitment drive by dispatching his proposed officers on a tour to enlist soldiers. As part of this effort, Colonel Kovats himself traveled to the Easton-Bethlehem area of Pennsylvania, where he arrived on April 16.[25]

According to German-language records from the Protestant community in Bethlehem, Kovats had visited this predominantly German settlement previously and relied significantly on the local population for supplies and provisions.[26] Having mastered the German language during his extensive service in Prussia and being well-versed in German customs and culture, Kovats was able to connect well with the local community. His references to his time serving in the army of Frederick II (the Great) likely endeared him to the German-speaking residents, who, as evidenced by these records, were eager to welcome the experienced and charismatic former Hussar officer. The German-speaking community’s familiarity with Kovats, combined with his linguistic and cultural affinity with them, made the area an ideal location for enlisting soldiers, providing a vital source of manpower for the growing unit. This strategic use of local resources and connections contributed to the early success of the Legion’s recruitment efforts.[27]

Bethlehem was also where the nascent Legion received its own battle flag. The Moravian Lutheran Sisters, often referred to as the Protestant ‘nuns’ of the Moravian Brethren of Bethlehem, are credited with crafting the red-white-green flag, one of the few surviving military flags from the Revolutionary War and one of the first flags to bear the abbreviation “US.” The flag’s design was created under the direct orders of Kováts.[28]

To help cover the significant costs of recruiting and equipping the Legion, the Continental Congress allocated $50,000 to Pułaski in a resolution passed on April 6, 1778. This funding was critical in enabling Pułaski and Kovats to recruit soldiers, purchase necessary supplies, and support the early efforts to establish the Pułaski Legion.[29] Recruiting, however, proved to be a challenging task. The Continental Congress granted Brigadier Pułaski permission to enlist 68 cavalrymen and 200 infantrymen for the Free Corps. Despite this authorization, the process of filling the ranks was fraught with complications, as evidenced in a letter dated May 1, 1778 from Washington authorizing Pułaski to supplement the Legion’s numbers with British prisoners, but only those who were deserters. Additionally, Washington stipulated that no more than one-third of the recruits could be former German (Hessian) soldiers.[30] Given Pułaski’s lack of experience with German soldiers—whether Prussian or Hessian—and his inability to speak German, it is clear that the proposal to enlist these deserters likely reflected the influence and expertise of Colonel Kovats, who, having served in the Prussian military and being fluent in German, was well-suited to manage the complexities of recruiting and integrating German-speaking soldiers.

Interestingly, the first combat mission of the Pułaski Legion is more closely associated with Colonel Kovats than with Brigadier General Pułaski. In July 1778, British forces, along with Hessian and Native American allies, launched an invasion of Wyoming Valley in northeastern Pennsylvania, a region fraught with tensions between settler communities and indigenous tribes. The British and their allies inflicted heavy casualties, killing at least 400 local militia members. In response, the governor of Pennsylvania called on the Pułaski Legion to intervene.[31] While Pułaski remained in Trenton overseeing the Legion’s infantry, Kovats took command of a small cavalry force and was dispatched to pacify the Wyoming Valley area.[32] Kovats’ leadership in organizing the response highlighted his growing influence within the Legion and the success of its early operations.

After receiving no orders for active service against the enemy for an entire month, Brigadier General Pułaski grew frustrated. On September 17, he sent an urgent letter to Congress, requesting that his legion be deployed to active duty as soon as possible. Pułaski emphasized the need for his troops to engage in the conflict, highlighting the delay and the importance of maintaining momentum in the ongoing war.[33] Two days later, Washington ordered the Pułaski Legion to march to Fredericksburgh, New York, and then to join Gen. William Alexander’s command in Paramus, New Jersey, where British forces were concentrated around New York. This movement was part of a broader strategy to counter British blockades that had effectively sealed off New York Harbor and Delaware Bay, preventing French and European supply ships from reaching the American colonies. In response, American smugglers had established Egg Harbor, near Tuckerton on the New Jersey coast, as a key point for unloading goods destined for Philadelphia. To disrupt this activity, the British navy launched an operation to seize the harbor. In response, Washington ordered the Pułaski-Kovats Legion, along with artillery, to secure the area around “Middle of the Shore” (later Tuckerton) on October 4.[34]

From Tuckerton, the Pułaski-Kovats Legion advanced to Great Egg Harbor, a strategically important location for Continental shipping. There, they successfully thwarted a British landing attempt, relieving the local militia stationed at Osborne Island and securing the area from further British incursions. This action helped safeguard a critical supply route for the Continental forces.[35] The Pułaski-Kovats Legion and the artillery incurred significant losses during this operation. In addition, Pułaski reported severe fatigue and exhaustion of his troops, despite having only been engaged in active combat since early October. In response to these hardships, Congress authorized the Legion to repair and occupy Sussex Court House near Trenton, providing them with a much-needed respite to replenish their supplies and recover.[36]

On November 15, 1778, Pułaski reported to Washington that the Legion had been placed under the command of Colonel Kovats for the winter.[37] Pułaski had traveled to Philadelphia, where he would remain for the winter months. In his letter to Kovats on December 16, Washington named Kovats “commanding officer of Casimir Pulaski’s corps.”[38]

Long March to Charlestown, South Carolina

By now, the strategic focus of the war was shifting southward. In the Carolinas and Georgia, the Loyalist base was stronger, and the terrain was more favorable for British naval operations. Moreover, British economic interests in global trade made the possession of the southern states a top priority. The British aimed to capture key southern cities, especially Charlestown (today Charleston)—the South’s most important and wealthiest port—which, if taken, would likely restore British control over the southern colonies, a scenario that Washington and Congress could not afford to let happen. Therefore, Congress authorized the deployment of the Pułaski-Kovats Legion to South Carolina on February 2, 1779, placing it under the command of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln.[39] An appropriation of 15,000 Continental dollars was allocated to Pułaski for recruiting and travel expenses.

In the early spring of 1779, the Legion embarked on a forced march from Easton to Charlestown, covering a distance of over 600 miles. Kovats, accompanying the legion’s infantry, played an active role in this arduous journey. By the time the infantry corps reached Charlestown, it had been reduced to little more than half its original strength.[40]

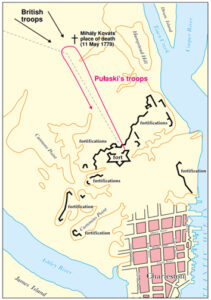

Brig. Gen. William Moultrie, who was present during the defense of Charlestown, recounted that Pułaski’s infantry and cavalry entered the city on May 8.[41] On May 10, 1779, British forces reached Ashley Ferry and crossed the river without opposition. The next day, Pulaski’s legion, along with some militia, skirmished with the British advance guard. The attack was quickly overwhelmed, resulting in heavy losses for Pulaski’s forces, including the death of Colonel Kovats. Most of Pulaski’s infantry were either killed, wounded, or captured, and only a few managed to return to the safety of Charleston’s lines. The skirmish took place near the Nightingale racecourse, just east of the present-day Line and Meeting streets. [42]

Dr. Joseph Johnson, drawing from his childhood memories and later research, described the circumstances of Kovats’ death. He wrote that Kovats fell from his horse during the retreat and was buried on the side of the road near Huger Street. He noted that Kovats, a Hungarian-born officer and former Hussar under Frederick the Great, had distinguished himself in military service and had been awarded the Cross of Merit.[43]

British officer Maj. Francis Skelly recorded that British dragoons and infantry advanced close to Charlestown, while another cavalry contingent conducted reconnaissance. Pulaski’s Legion, consisting of around 100 infantry and 80 cavalry, was stationed near a breastwork. Pulaski’s cavalry advanced toward the British dragoons, who charged and completely routed them, driving the cavalry through the breastwork and attacking the infantry. Colonel Kovats, commanding the infantry, was killed along with fifteen or sixteen of his men. Several cavalry officers and privates were captured, with the total losses of the Legion numbering between forty and fifty. [44]

Although Major Skelly’s account contained errors, particularly regarding specific details of the battle, it provides a unique and valuable perspective on the events. The British officer’s description highlights the bravery and skill of Pułaski’s cavalry, which Skelly lauded as “the best Cavalry the rebels ever had.” This praise acknowledges the high standard of the American light cavalry, a force largely shaped and trained by Col. Michael Fabriczy Kovats. Despite Kovats being assigned to command the infantry, an unfamiliar role for him, British recognition of the effectiveness of his cavalry underscores his immense contribution to their training and readiness, underscoring his legacy as a military leader who overcame significant challenges to elevate the quality of the Continental Army’s cavalry.

Kovats as a Hungarian-American Icon

Today, Michael Kovats’ legacy is commemorated across the United States through a diverse array of memorials, monuments, and exhibitions that collectively honor his role in the American Revolution. In New York City, Kovats is memorialized by De Kovats Triangle and Playground, while an equestrian bronze relief by Alexander Finta, housed at the New York Historical Society, captures his military contributions. Washington, D.C. now hosts three prominent memorials to Kovats: an equestrian statue by Paul Takacs at the Embassy of Hungary; a smaller equestrian statuette by Finta at the Society of the Cincinnati; and the recently unveiled a bronze memorial relief by Sándor Györfi at the Kossuth.

In Charleston, South Carolina, Ilona Bodo’s painting of “Kovats’ charge” in 1779 is held at The Citadel, where a bronze memorial relief has also been placed by the American Hungarian Federation. Kovats’ legacy is also honored by a historical marker placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution at the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon in Charleston, along with a reproduction of the red, white, and green flag designed by Kovats, donated by the Michael Kovats Memorial Committee.

Kovats’ legacy is further celebrated through a diverse array of cultural works such as plays, poems, and musical compositions, including two distinct “Kovats Marches.” These memorials, spanning more than a century, reflect the admiration of generations of Hungarians, Americans, and Hungarian Americans, acknowledging Kovats’ role in the American Revolution and highlighting the historical connections between Hungary and the United States.

Yet, a crucial chapter of his story remains unfinished: his final resting place, thought to be somewhere near Hugers Street in Charleston, is still unknown. Archaeologists are actively searching for his burial site, with the hope of finally locating his remains and giving this unsung hero the recognition he deserves in the city he fought and died to defend. The rediscovery of Kovats’ grave would offer Charleston and the nation an opportunity to properly honor this Revolutionary War hero, adding a Hungarian name to the distinguished list of Patriots who sacrificed their lives for liberty in the American Revolution.

[1] Lee F. McGee, “European Influences on Continental Cavalry” ed. by Jim Piecuch, Cavalry of the American Revoltuion (Westholme Publishing, 2012), 45.

[2] “Original documents demonstration against Charleston, South Carolina, in 1779, Journal of brigade major F. Skelly,” ed. Martha J. Lamb, in The Magazine of American History 26 (1891), 152-153.

[3] Zoltán Árpád Pintér, Fabriczy Kovats Michael. A Hungarian Hussar Officer on Two Continents (Zrínyi Kiadó, 2021), 241.

[4] Ibid., 139.

[5] The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 23, October 27, 1776, through April 30, 1777, ed. William B. Willcox (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983), 173.

[6] Worthington Chauncey Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Volume VIII (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 384.

[7] Aladár Póka-Pivny – József Zachar, Colonel Michael Kovats – A Hungarian Hero of the American War of Independence (Zrínyi Military Publishing House, 1982), 103.

[8] Martin. I. J. Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski: The father of the American cavalry,” The American Catholic Historical Researches 6. no. 1 (1910): 7.

[9] Ibid., 9.

[10] Ibid., 11.

[11] Miecislaus Haiman, Poland and the American revolutionary war (Polish Union Daily, 1932), 28.

[12] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, Count Casimir Pulaski to George Washington, November 23, 1777, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.045_0844_0851/?sp=1.

[13] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski,” 26.

[14] Actually, a free hussar unit. The name of the light cavalry force recruited by Frederick the Great, from 1745 from the Balkans, Hungary and Russian territories.

[15] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, Count Casimir Pulaski to George Washington, December 29, 1777, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.046_0584_0585/?sp=1.

[16] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski,” 31.

[17] Ibid., 34. Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, Count Casimir Pulaski to George Washington, January 9, 1778, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.046_0913_0914/?sp=1.

[18] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Henry E. Lutterloh to John Laurens, January 14, 1778, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.046_1033_1038/?sp=4.

[19] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Michael de Kowats, February 4, 1778, Clothing and Leather Goods Account, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.047_0237_0238/?sp=1.

[20] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski,” 43.

[21] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Count Casimir Pulaski to George Washington, February 28, 1778, www.loc.gov/item/mgw449620/. Haiman, Poland and the American revolutionary war, 29.

[22] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: George Washington to Continental Congress Conference Committee, April 9, 1778, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.048_0570_0571/?sp=1.

[23] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 10:364.

[24] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski,” 44-45.

[25] Haiman, Poland and the American revolutionary war, 48.

[26] Joseph Mortimer Levering, A history of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1741-1892 (Bethlehem, PA: Times publishing company, 1903), 486-487.

[27] Ibid., 485-486.

[28] László Örlős and Anna Smith Lacey, “The Forgotten Hungarian Origins of the Pułaski banner,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 3, 2024, allthingsliberty.com/2024/12/the-forgotten-hungarian-origins-of-the-pulaski-banner/.

[29] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 10:312.

[30] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, George Washington to Count Casimir Pulaski, May 1, 1778, www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.049_0017_0018/?sp=1.

[31] Haiman, Poland and the American revolutionary war, 48. Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania – Transcript of the order of the Supreme Executive Council: HM HIM HL Personalia VII. 148. fond 131. box 131. box Fol. 21.

[32] Typescript of the letter: HM HIM HL Personalia VII. 148. fond 131. box Fol. 22.; Levering, A history of Bethlehem, 486.

[33] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski”, 67.

[34] Ibid., 69.

[35] Póka-Pivny – Zachar, Colonel Michael Kovats, 121.

[36] Griffin, “General Count Casimir Pulaski”, 76.

[37] Ibid., 77-79.

[38] Library of Congress, Manuscript Archives, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: George Washington to Commanding Officer of Count Casimir Pulaski’s Corps, December 16, 1778, www.loc.gov/item/mgw452905/.

[39] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 13:132.

[40] Adelaide Lisetta Fries, Records of the Moravians in North Carolina. Volume III: 1776-1779 (Raleigh, Edwards & Broughton Print. Co., 1926), 1282-1283.

[41] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, so far as it related to the States of North and South Carolina and Georgia. Vol. I., (David Longworth, 1802), 423-424.

[42] Edward McCrady, The history of South Carolina in the revolution, 1775-1780 (Macmillan & Co, 1901), 357-358.

[43] Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Walker & James, 1851), 244-245.

[44] “ Journal of brigade major F. Skelly,” 152-153.

One thought on “Colonel Michael Kovats: The Hungarian Co-founder of the American Cavalry”

Great article! Great timing too! I just discovered an interview with a great-grandfather who immigrated to America from Poland in the late 1890s. In the interview, he repeatedly stated that his inspiration to come to America was based on stories he heard about from his great-grandfather serving in Pulaski’s Legion during the war. I was blown away as I never knew I had a personal connection to the war, especially on my Polish side. Needless to say, this has sent me down a deep rabbit hole. I’ve been reading anything Pulaski Legion. Apparently, he was one of the enlisted members of the Legion who came from Poland, served for two years, and then returned to Poland.