The Revolutionary War in the Ohio and Upper Mississippi River Valleys is generally looked upon as a side show to the main conflict along the Atlantic Seaboard. However, the impact of the forces in the Old Northwest Territory was much greater than their small size could have anticipated. Historian Pauline Peyton posited that had the British retained the Old Northwest Territory, Chicago and Detroit might be two of the great cities of Canada and the Louisiana purchase might never have happened.[1] Without the accomplishments of the western patriots, the United States might have retained a decidedly Atlantic Seaboard character and Manifest Destiny may not have driven the political conversations of the nineteenth century. George Rogers Clark’s Illinois Regiment of Virginia Troops is generally given most of the credit for establishing American claim to the Old Northwest through the capture of Kaskaskia (now Illinois) and Vincennes (now Indiana), but the initial capture of both formerly French colonial villages was in part due to the efforts of Pierre Gibault, a French Canadian priest.

Clark raised his Illinois Regiment in early 1778. On July 4 he and his forces arrived outside of Kaskaskia. A former French colonial outpost, Kaskaskia was a small community that had been the site of the last British garrison in Illinois. When Clark and his men arrived they found no British soldiers present. They captured the acting British governor, former French army officer Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave. The citizens of Kaskaskia were told to remain in their homes while the Americans secured the village. They now had to prepare to capture Cahokia to the north along the Mississippi River. The local parish priest, Pierre Gibault, came to Clark along with five or six “aged citizens” to ask to permission to gather for mass in the local church. Clark appears to have won over Gibault at that meeting. Gibault was then able to calm the Kaskaskians as well as assist Clark’s force on securing Cahokia without bloodshed. Historian Joseph J. Thompson offers a slightly different and more detailed version, writing that Clark’s spies Ben Linn and Samuel Moore reached Kaskaskia and engaged with Daniel Murray, a local trader, who assisted in building support for the American cause prior to Clark’s arrival. Murray had notified Gibault of the impending arrival of American troops and was asked to ensure the French inhabitants would be docile, if not supportive of the Continental troops.[2]

Pierre Gibault was born on April 7, 1737, in Montreal, Quebec. His grandfather Gabriel Gibault and his wife appear to have emigrated to Quebec from France sometime after 1663. His father and namesake Pierre married Marie-Joseph Saint-Jean at Sorel in 1735.[3] Pierre was their first child.[4] According to the Rev. J Sassevile, after Gibault completed classical studies at the seminary of Quebec, he travelled for some time in the “countries of the west,” probably meaning the current Great Lakes region. Most likely he was somehow engaged in the fur trade. He then entered the seminary at Quebec and completed his theological studies. He received minor orders and the tonsure in 1766.[5] Gibault was ordained in the seminary chapel on March 19, 1768. Gibault said his first mass in the Ursuline Church in Quebec and was initially assigned to the Quebec Cathedral in 1768.[6]

The year prior, the Bishop of Quebec, Jean-Olivier Briand, had received a request for at least four priests to assist in ministering to the faithful in the Illinois Country.[7] Briand promised to send one or two priests to the Illinois Country the following year. Gibault was selected to travel to the Illinois County and support Father Meurin, the vicar general for the Illinois Country.[8] Gibault left Quebec and first travelled west to Michilimackinac where he arrived in July 1768. He was appointed as vicar-general for “Illinois and Tamaroa” and “all further places in our diocese to which you may come” in a letter from Briand to Gibault dated May 30, 1768.[9]

Gibault was planning to remain for twenty-four hours only but spent that entire time hearing the confessions of traders and those Indian converts who spoke French. He was not able to hear the confessions of Catholic Indians who did not speak French. He administered the sacraments to the faithful, including many baptisms since Michilimackinac had not had a priestly visit since 1761.[10] Unwilling to delay his trip to the Illinois Country any longer, he left after a week.[11] He appears to have travelled to Green Bay and then down the Fox River to the present site of Prairie due Chein, Wisconsin, where he took the Mississippi down river to the American Bottom area of Illinois opposite Modern St. Louis, Missouri.

Gibault was intended to be assigned as pastor of the old Tamarois mission at Cahokia, but the church had apparently fallen into decay and an element of the 34th Regiment of Foot was using the rectory and possibly the church itself as a fort and barracks. It appears Gibault attempted to get the British to evacuate his proposed parish, but the regiment’s commander was not willing to do so.[12] The parish of the Holy Family at Cahokia had been asked to subsidize Gibault’s seminary tuition, but for a variety of external constraints, Gibault placed himself at Kaskaskia, where there was also a subaltern’s guard from the 34th Foot. Kaskaskia was the largest of the villages of the American Bottom. Father Meurin, the only remaining priest in Illinois, retained responsibility for Cahokia and Prairie du Rocher, the closest settlement to Fort Chartres.[13]

Gibault appears to have gained at least some fluency in English and eventually in one or more of the Indian tongues.[14] Gibault appears to have been able to work under the British troops in Illinois at least after September 1768, when the 34th Regiment was replaced by the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment. Gibault wrote to Bishop Briand on June 15, 1769, that “Our commandant offered me his support and that of his troops if I should need them for our religion. As it is an Irish regiment where there are many Catholics, he has asked me to treat those who are of the faith as I would my parishioners.”[15] It is not clear how many of the 18th Foot were practicing Catholics, if any, as enlisting Catholics into the British Army at the time was prohibited. Unfortunately, although Gibault was fairly meticulous about recording baptisms and marriages, his burial records inconsistent and sometimes only half completed, so we do not know how many funerals of British soldiers he may have officiated. Gibault baptized mostly French children but according to historian Joseph P. Donnelly, he included a “noticeable number of Indians and Negroes.”[16]

A petition from the parishioners of Vincennes to the Bishop of Quebec caused the Bishop to order Gibault and Meurin to travel to Vincennes for a month or so to minister to the community. They remained two months as the community had not seen a priest in seven years.[17] Gibault travelled to the Spanish side of the river to bless the first chapel at what would become modern St. Louis, Missouri. When Gibault set off for Vincennes in the winter of 1769-1770, he carried a longarm and two pistols because more than a score of travelers had been killed and scalped in the vicinity by hostile Indians. Gibault appears to have been captured by Indians on at least three occasions and was only released by promising not to reveal their presence in the area.[18] Gibault would return to Vincennes in 1775 as part of a longer missionary trip to the settlements and Indian villages at Peoria, St Joseph’s (Michigan), Michilimackinac, the Miami (near the western tip of Lake Michigan), and Ouiatenon (present day West Lafayette, Indiana).[19]

Records are contradictory as to whether Gibault’s mother and sister travelled with him to Illinois in 1768, but they were both present in Kaskaskia by 1770.[20] On September 11 of that year, his sister Marie Louise Gibault married local habitant Joesph Nigneau. Gibault’s mother appears to have passed away in May 1775. Gibault finished his trip at Detroit, hoping to be allowed to return to Quebec, but Bishop Briand refused his request and he returned to Kaskaskia.[21]

Gibault’s missionary travels appear to have turned his local parishioners against him and when the British Garrison was reduced in June 1772, “public order and morality rapidly degenerated.” In part, Gibault was covering both sides of the Mississippi as well as traveling to the former French settlements at St. Joeph, Vincennes, and Michilimackinac.[22] These concerns reached the bishop in Quebec, who wrote to Meurin asking about Gibault’s conduct. Meurin wrote that Gibault was loved at first, but he became too free—he was familiar with the ladies, stayed out late, played cards, celebrating and the like. “he showed the French habitants that he could drink as much or more than they,” Meurin wrote, including the names of former Jesuits whom the locals still held in fond memory.[23] The death of his mother in 1775 and Fr. Meurin’s death in 1777 seem to have cooled the concerns against him. It was at this time when Clark’s Virginians arrived in Kaskaskia.

George Rogers Clark with approximately 175 troops arrived at Kaskaskia in the late evening of July 4, 1778, after tramping overland from the ruins of the French Fort Massac (near modern Metropolis, Illinois). The trip had taken longer than expected. Clark’s men had run out of rations about two days previously. Due to the delay, Governor Rocheblave had allowed the militia to stand down after earlier warnings of an impending attack, and the village was taken without firing a shot. Gibault met with Clark the next day and was given assurances that he could continue to minister to his parishioners and say mass. This assurance from Clark, in the opinion of one historian, was more significant than those in our modern secular world might be able to fully understand. The French Canadian habitant “in America, desired above all else peace and economic security. He desired too, freedom to practice his religion with a strength of desire we can hardly exaggerate.”[24] These assurances, which Gibault appears to have found genuine, did more than gunpowder and ball to take control of the Illinois Country. Gibault was among the first to take the oath of allegiance to the Continental Congress on July 5. He seems to have absolved his parishioners from their earlier oath of allegiance to the British Crown.[25]

Clark sent troops to secure Cahokia and those citizens took the oath of allegiance on July 8. It is not clear if Gibault helped to convince his parishioners at Cahokia. He offered to go to Vincennes to convince them of the value of the American cause, but he did not want to lead the expedition as he had “nothing to do with temporal business, that he would give them such hints in the Spiritual Way, that would be very conductive to the business.”[26] Clark tapped, or Gibault suggested, Jean Baptiste Laffont, a local physician, to lead the embassy to Vincennes. Gibault and Laffont left on July 14 and arrived three days later. Gibault again provided absolution for those who swore alliance to America. Gibault’s “spiritual” influence may be seen in that, at Vincennes, the American oath of allegiance was taken in the Catholic church in the village.[27] It isn’t clear if Clark entirely trusted Gibault at this point, as he may have sent a spy among Gibault’s party to Vincennes.[28] Within a couple of weeks Gibault and his party returned with positive news.[29] According to Clark’s journals, he gave Gibault the British flag taken from Vincennes.[30]

In the next months, the British retook the fort at Vincennes, and rumors of British Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton’s imminent arrival to retake Kaskaskia began to arrive among Clark and the French inhabitants. According to Clark, Gibault was the most agitated at the potential of Hamilton’s arrival as Gibault felt he would be a particular target of British vengeance. This was, in fact, accurate—Hamilton wrote to Gov. Frederick Haldimand that he was anxious to capture Gibault.[31] Clark found an excuse to send Gibault to the Spanish side of the Mississippi with “Publick Papers and money,” but Gibault ended up spending three days on a frozen island in the middle of the river.[32] Returning to the Illinois side on January 5, 1779, Gibault accompanied Clark’s troops as they set out on a “forlorn hope” to capture Vincennes. Clark recorded, “Mr. Jeboth [Gibault] the Priest, who after a very suitable Discourse to the purpose, gave us all Absolution” before the troops set off across the frozen prairie.[33]

Patrick Henry, governor of Virginia, wrote to Clark on December 15, 1778, “I beg you will present my compliments to Mr. Gibault and Doctor Lafont and thank them for their good services for the state.” There was some discussion about engaging Gibault to liberate the inhabitants of Detroit from their British masters, but that plan didn’t come to fruition. The British leadership may have viewed Gibault’s actions differently. Lieutenant Governor Hamilton wrote after his capture at Vincennes that one of the French militia deserters was a brother of Gibault, “who had been an active agent for their rebels and whose vicious and immoral conduct was sufficient to do infinite mischief in a country where ignorance and bigotry give full scope to the depravity of a licentious ecclesiastic. This wretch it was who absolved the French inhabitants from their allegiance to the King of Great Britain.” Hamilton went on to mention that the French were without virtue, but the “most eminently vicious and scandalous” was Gibault.[34]

Gibault did not provide only spiritual support. Gibault provided his own funds for Clark’s troops to purchase supplies during the 1778-1779 period which he tried to recover in 1783.[35] Gibault then moved to Ste. Genevieve in Spanish Territory sometime in 1780. It is not clear why he removed himself, but it could be due to the anticipated British campaign that ended in the Battle of St. Louis on May 26, 1780. Donnelly posited that Gibault’s move may have been due to the “notoriously contentious character of the Kaskaskians.”[36] The other possible reason for Gibault’s removal to Spanish Territory, and perhaps the most likely, was the ire of pro-British Bishop Briand. Briand, who some historians credit in part with keeping Canada and Canadians within the British sphere of influence during the war, suspended Gibault’s ecclesiastical functions in a letter dated June 29, 1780, for collaborating with the Americans. It does not appear Gibault paused his ministrations to his parishes. It is possible Gibault did not receive the letter.[37]

Gibault completed his last will and testament at Ste. Genevieve on September 8, 1782.[38] He did appear to occasionally travel to Illinois to minister to his parishioners; he sang a high mass for a Kaskaskian parishioner who in 1782 ended up in court for not paying Gibault for his services. Gibault remained in Ste. Genevieve until 1785 when he returned to Vincennes. He was replaced at Ste. Genevieve by Rev. Paul de Saint Pierre.[39]

With Gibault’s return to Vincennes, it obtained its first resident pastor since being established in 1731.[40] In order to lure Gibault back to Vincennes, the parishioners agreed to build a new church. Gibault wrote to the Bishop of Quebec in June 1786 asking for permission to build St. Francis Xavier on the Wabash.[41] When the First American Regiment came to Vincennes in the summer of 1787, its commander mentioned to his wife that Father Gibault was part of a dinner in honor of Colonel Jean Marie Philippe La Gras on August 2 held by the regiment’s officers.[42] A second dinner for the officers was held by Francis Vigo on August 4.[43] Most likely, Gibault attended this event as well.

Though Gibault seems to have been well received by his parishioners, he was still struggling with his ecclesiastical superiors. With the end of the Revolution, the Illinois Country was shifted from the Diocese of Quebec to the new American Diocese of Baltimore. The new vicar general was Rev. Pierre Heut de la Valiniere, a French Canadian who had been expelled from Canada for supporting the American cause. It would seem Gibault and de la Valiniere should have gotten along, but Gibault still felt he served the vicar-general of the Bishop of Quebec. The latter arrived in Kaskaskia in the summer of 1786. De la Valiniere returned to New York in 1786 leaving Gibault no direct superior save John Carroll, who had been appointed by Pope Pius VI as the Prefect Apostolic of the United States in 1784.[44] When Carroll announced a holy year of jubilee be proclaimed in 1785, Gibault wrote to Quebec for guidance on who his superior was, the Bishop of Quebec or the new America prefect.[45]

Gibault returned to Cahokia in 1789 but visited Vincennes at least once more when he was nearly killed by hostile Indians on his missionary journeys. Another priest was killed and a second wounded in the area in 1788. Gibault asked to be recalled in Quebec in May 1788 so he would not have to serve under a Spanish or an American bishop, but due to his adherence to the American cause, he was not allowed to return home. [46] As part of the settlements after the Revolution, Gibault wrote to obtain a grant in 1790 of the seminary lands at Cahokia as compensation for his losses in the war. Although President Washington approved the request, Bishop Carroll protested this as he saw Gibault as trying to personally gain from Church property and the decision was reversed. Gibault viewed this as a final insult from the new American Bishop and he removed to the Spanish side of the river.[47]

By June 1792, Gibault was at New Madrid as their pastor. He visited the Arkansas Post to perform twenty marriages and thrity baptisms between September 1792 and 1793. He finally took the Spanish oath of allegiance on December 23, 1793.[48] He remained in New Madrid until his death on the morning of August 16, 1802.[49] When he died, Gibault’s possessions included a library of 243 volumes that he had gathered since arriving in Kaskaskia in 1768.[50]

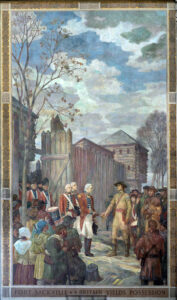

On June 14, 1936, a sculpture of Gibault along with one of Francis Vigo were unveiled at the same time the Geroge Rogers Clark Memorial on the site of Fort Sackville was dedicated by President Roosevelt at Vincennes, Indiana. Gibault’s statue is before the old cathedral.[51] During World War II, the U.S. Maritime Service named fifteen ships after prominent Catholics in American history, including one named for Gibault and others for his more famous contemporaries, John Carroll, the first US Bishop, and Junipero Serra, the founder of the California Missions.[52]

Father Pierre Gibault was one of the most underrated yet crucial figures of the American Revolution. His diplomatic efforts and spiritual leadership directly facilitated the bloodless capture of Kaskaskia and Vincennes, helping George Rogers Clark establish an American claim to the Old Northwest. Without his influence, the region might have remained under British control, drastically altering the course of U.S. expansion, and potentially reshaping the future of the Midwest. Though he later downplayed his role, his actions demonstrated the power of faith and diplomacy in wartime. His ability to unify and persuade French settlers, combined with his willingness to support the American cause despite personal risk, underscores his importance in securing the Illinois Country for the fledgling United States.

Gibault’s legacy, though often overshadowed by military leaders, is a testament to the crucial role that non-combatants played in shaping history. His work helped lay the foundation for American expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains, ensuring that the Old Northwest became a cornerstone of the new republic. While statues and ships bear his name, his true legacy lies in the influence he wielded during one of the most pivotal moments in American history.

[1] Pauline Lancaster Peyton, “Pierre Gibault, Priest of Patriot of the Northwest in the Eighteenth Century,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia vol. 2 no. 4 (1901): 452–98.

[2] Joseph J. Thompson, “Penalties of Patriotism: An Appreciation of the Life, Patriotism and Services of Francis Vigo, Pierre Gibault, Gorge Rogers Clark, and Arthur St. Clair, ‘The Founders of the Northwest,’” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984), vol. 9 no. 4 (January 1917): 401-449.

[3] Gibault’s mother’s name was alternatively listed as Mary St. Jean Tanguay.

[4] Thompson, “Penalties of Patriotism,” 45; Joseph P. Donnelly, “Gibault (Gibaut), Pierre,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2025, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gibault_pierre_5E.html.

[5] Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 454. Tonsure was the shaving of the top of the seminarian’s head to show his intention to become a priest and renounce the world, a practice made optional in 1972 which has fallen into disuse. Kevin Di Camillo, “What were the minor orders? And Why to they matter?,” National Catholic Register, December 13, 2018, www.ncregister.com/blog/what-were-the-minor-orders-and-why-do-they-matter.

[6] J. Sasseville, “Very Rev. Pierre Gibault, the Patriot Priest,” Catholic Historical Researches, vol. 2 no. 3 (January 1886): 117-119.

[7] André Vachon, “Briand, Jean-Olivier,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/briand_jean_olivier_4E.html.

[8] J. B. Culemans, “Catholic Explorers and Pioneers of Illinois,” The Catholic Historical Review, vol. 4 no. 2 (July 1918), 164.

[9] Joseph P. Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 1737-1802 (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1971), 38.

[10] Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 468. Father M. L. Le Franc had last visited the post in 1761.

[11] John Gilmary Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, Bishop and First Archbishop of Baltimore (New York: John G. Shea, 1888), 125.

[12] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 47.

[13] Sebastien Louis Meurin (1707-1777) was a French Jesuit who served in French Illinois until the French recalled all Jesuits to France in 1763. When Meurin arrived in New Orleans, he pleaded to be allowed to return to the parishes in modern Illinois and Missouri. In order to return upriver, Meurin was required to swear obedience to the Sulpician superior at New Orleans and disavow his earlier commitment to the Jesuits. He died at Prairie du Rocher in 1777. See missouriencyclopedia.org/people/meurin-sebastien-louis.

[14] According to Peyton, Gibault was able to move freely among those populations. Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 473.

[15] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 49.

[16] Ibid., 48. According to Donnelly, Gibault baptized 243 persons from October 1, 1768 through 1778.

[17] Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 473. The previous priest had left a layman charged with performing and recording lay baptisms, but otherwise there had been no religious influence

[18] Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, 127-129.

[19] Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 477.

[20] Louise Phelps Kellogg, The British Regime in Wisconsin and the Northwest (Madison: Wisconsin State Historical Society, 1935), 94. Kellog states Gibault’s mother and sister accompanied him on his initial voyage to Illinois but other sources state they arrived by 1770. Kellog is probably correct.

[21] Peyton, “Pierre Gibault,” 476-478; Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 48.

[22] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 54-56.

[23] Ibid., 59.

[24] Samuel K. Wilson, “Bishop Briand and the American Revolution,” Catholic Historical Review, XIX (1933), 135.

[25] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 68; George Rogers Clark, Sketch of His Campaign in the Illinois in 1778-9 (Salem, NH: Ayer Company Publishers, 1991), 34; Kellogg, The British Regime, 152.

[26] Clark, Sketch of His Campaign, 35-36.

[27] Culemans, “Catholic Explorers and Pioneers of Illinois,” 165-166.

[28] Clarence Walworth Alvord, “The Oath of Vincennes,” The American Catholic Historical Researches, New Series vol. 7 no. 4 (October 1911), 395.

[29] Clark, Sketch of His Campaign, 36. Alvord gives the date of Gibault’s return to Kaskaskia as around August 1, 1778. Alvord, “The Oath of Vincennes,” 398.

[30] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 72.

[31] Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, 187.

[32] Clark, Sketch of His Campaign, 56.

[33] Ibid., 65. In his memoirs, Clark always referred to Gibault as Jeboth.

[34] Culemans, “Catholic Explorers and Pioneers of Illinois,” 167-168.

[35] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 100-104.

[36] Ibid., 100.

[37] Stephen L. Kling, The American Revolutionary War in the West (St. Louis: TCHG Publishing, 2020), 167; “Gibault (Gibaut), Pierre,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

[38] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 101-102.

[39] Ibid., 100-110. Kling provides alternative date of return of 1784. Kling, The American Revolutionary War in the West, 170.

[40] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 111-112.

[41] Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, 470.

[42] Also Legrace; he was a merchant at Vincennes prior to the arrival of Clark’s troops served Clark as a principal purchaser of military supplies. Motion on letter from J. M. P. Le Gras [9 May] 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-02-02-0019.

[43] Florence G. Watts, “Fort Knox: Frontier Outpost on the Wabash, 1787-1816,” Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 62 no. 1 (March 1966), 59.

[44] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 117-119.

[45] Ibid., 113.

[46] Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, 471.

[47] Ibid., 472; “Gibault (Gibaut), Pierre,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

[48] Donnelly, Pierre Gibault, Missionary, 131-137.

[49] Ibid., 148. Shea gives his date of death as 1804 based on a notification by Rev. Gabriel Richard to Bishop Carroll on May 1, 1804. Shea, Life and Times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, 472.

[50] Howard H. Peckham, “Books and Reading on the Ohio Valley Frontier,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 44 no. 4, 657. For more information see John F. McDermott, “The Library of Father Gibault,” Mid-America (Chicago), XVII (October 1935), 273-275.

[51] Louise Phelps Kellogg, “The Society and the State,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 20 no. 1 (September 1936): 115-123. George Rogers Clark Memorial, National Park Service, www.nps.gov/gero/learn/historyculture/memorial.htm.

[52] “Floating memorials,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 58 no. 3, 188.

One thought on “Father Pierre Gibault, Revolutionary Priest”

Love this piece. Gibault was one of the most fascinating people in the Illinois Country during the Revolution and critical to our understanding of the war west of the Appalachians.