The adjectives leveled Benedict Arnold’s way by contemporaries and historians leave little room for doubt. Though he inspired devotion among those serving under him, the man rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. Prickly, heavy-handed and arrogant, he seemed to thrive on personal confrontation with those who differed with him. The famous clash between Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold over command of the Patriots’ mixed force of volunteer militiamen and Green Mountain Boys in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 provides the most prominent example.

A detente between the two was reached prior to the attack itself. Alas, this uneasy truce was not to last beyond the first rush of victory. It ruptured completely when Arnold attempted to stop the Boys from an outbreak of raucous looting and celebration. He was answered with a firelock pointed at his breast. Ethan Allen intervened but defended his frontiersmen and allowed them to continue. The ensuing power struggle for command of the southern end of Lake Champlain lasted six weeks, until June 24 when Arnold resigned his commission at the behest of a delegation sent from Massachusetts’ Provincial Congress. Allen’s subsequent capture at Montreal and long-term imprisonment by the British precluded any further wartime contact between the two antagonists.

A second, long-running personal vendetta also launched in the immediate aftermath of the attack on Fort Ticonderoga. It has received much less attention. Benedict Arnold and James Easton of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, also faced off following the strike. Perhaps colored by Arnold’s later treason, historians have tended to portray Easton as an aggrieved victim. A closer look at the record suggests otherwise.

The story begins on September 1, 1774 when minute companies from all over Massachusetts responded to an alarm based on news that a detachment of redcoats had fired on Patriots defending a cache of military stores in Charlestown, near Boston. Lt. James Easton rode with Captain Noble’s company of Berkshire County militia. The alarm proved false and the men returned home. The two senior officers received a handsome £6 apiece for their service. That October, forty-seven-year-old James Easton, a church deacon and tavernkeeper, was commissioned a colonel in the county militia.[1]

It is unclear whether Easton again joined the host of colonials marching to Cambridge following the “Shot Heard Round the World” on April 19, 1775. If he did so, the stay was brief and he returned to home to Pittsfield by May 1. These two forays constituted the sum total of his military experience at the outset of the Revolutionary War.

Further south, at the outbreak of hostilities, thirty-four-year-old Benedict Arnold raced to Boston at the head of the 2nd Company of the Governor’s Footguard from New Haven, Connecticut. Though lacking military experience, he was a successful apothecary, dry goods trader and merchant sea captain. Ocean-going trading vessels under his personal command had sailed up and down the Atlantic coast as far south as the West Indies and north to the waterways of Canada for a number of years.

On arrival in Cambridge, Arnold arranged a meeting with the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to pitch the idea of an immediate assault on Fort Ticonderoga. The captured artillery would provide the necessary firepower to carry the day against the British occupation of Boston. The idea had already been suggested to the committee by Pittsfield’s John Brown, Esq. in March following his fact-finding mission on their behalf to Montreal.

Impressed by his military bearing and evident knowledge of the Lake Champlain corridor, the committee authorized the attack and engaged Arnold to lead it. He was commissioned colonel, provided with £100 in specie, two hundred pounds of gunpowder, horses, and quantities of flints and lead. The commission’s text conferred commander-in-chief authority throughout the Lake Champlain theater of operations and authorized him to recruit up to 400 men to effect the capture. Arnold promptly engaged two captains to enlist soldiers from the Stockbridge area and western Massachusetts. Hearing that a separate Connecticut initiative was in train, he galloped north so as not to miss out on the action.

Meanwhile, on May 1, two Connecticut captains also hastening to reach Ticonderoga, Edward Mott and Noah Phelps, stopped to refresh themselves at Easton’s tavern in Pittsfield. They met John Brown and the proprietor there. Both men were allowed to accompany them, with Col. Easton discretely engaging militiamen in western Berkshire County en route. According to Mott, Easton raised between forty and fifty men.[2]

Easton knew his recruits would be in line to receive travel expenses and wages once the British garrison surrendered, especially were they to continue in service. (Any representations he made to them on the road to Ticonderoga are unrecorded). In the rush of the departure he had no time to secure funds to meet these expenses. Thus, it seems he made it his first order of business after the capture to meet with Benedict Arnold and suggest that he be commissioned a Massachusetts lieutenant colonel and ask Arnold to use a portion of the expeditionary funds he carried to pay him and his men. It did not go well. He was shocked to be rejected out of hand. Arnold had reason to believe his recruiting officers were days away with a detachment of his own. Easton asked himself why the Massachusetts committee had chosen a sea captain from Connecticut instead of him to lead the colony’s troops. His resentment apparently boiled over.

Benedict Arnold, sensing he might have to defend himself at some point, decided to keep a record of his activities for future reference in a Regimental Memorandum Book. The first entry, on May 10, registered his version of their discussion: “This day Colonel Eaton [sic] taking umbrage at my refusing his Lieutenant Colonel’s . . . [commission?] set off for the Congress with an announced intention to injure me all in his power.”[3]

Easton’s rejoinder to Arnold’s rebuff was to race to Boston and be the first to deliver the news of the stunning coup de main on Lake Champlain—and play up his part in the drama. In a published account in The American Oracle, a Boston newspaper, Easton was reported to have clapped British Capt. William Delaplace on the shoulder and demanded the formal surrender of Fort Ticonderoga at the decisive moment.[4] Meeting secretly with the Committees of Safety and the Provincial Congress in Watertown near Boston, he disparaged Arnold and accused him of improper behavior to such a degree that they moved to send an investigative commission led by Walter Spooner to assess Arnold’s conduct and review his accounts. Easton also attempted to obtain provisions and much-needed gunpowder for the post—while seeking a Massachusetts colonelcy for himself. He had now irretrievably crossed a line with Arnold, a formidable, vindictive man—and he would come to regret it.

Meanwhile, Ethan Allen’s initial dispatches to the Continental Congress and Connecticut’s General Assembly took individual credit for leading the capture of Ticonderoga and pointedly omitted any mention of Arnold’s presence. Instead, he shamelessly embellished Easton’s role—an assertion firmly contradicted in contemporary accounts by disinterested parties on the British side, notably that of the garrison’s second in command, British Lt. Jocelyn Feltham.[5] Arnold later published his rebuttal to Allen and Easton under a pseudonym, Veritas, saying Easton “was the last man that entered the fort, and not till the soldiers and their arms were secured, he having concealed himself in an old barrack near the redoubt, under the pretense of wiping and drying his gun, which he said got wet crossing the lake; since which I have often heard Colonel Easton in a base and cowardly manner, Abuse Colonel Arnold behind his back, though always very complaisant before his face.”[6] Captain Delaplace, commandant of the garrison, later corroborated Feltham’s statement that Easton was nowhere to be seen at the moment of surrender.[7] The controversy set the stage for a pointed confrontation between Arnold and Easton some four weeks later, in the presence of Connecticut’s Maj. Samuel Elmore.

After the capture of the forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, Benedict Arnold turned his attention to making preparations for the expected counterattack from the British. Ever the realist, seemingly more than anyone else he grasped the degree of danger posed by the British garrisons in Canada and took action. He sailed an armed trading schooner with several batteaux in tow to the northern end of Lake Champlain. Striking at dawn on May 18, his men cut out a seventy-ton British sloop anchored at Fort St Johns, securing near-term naval supremacy for the Patriots. Arnold and his flotilla for now cruised unchallenged as masters of Lake Champlain.

By early June, Ethan Allen was nominally still in command at Fort Ticonderoga, but threatened with irrelevancy. Arnold’s recruiters had appeared on the scene with 150 men. Unsuited by temperament for garrison duty and anxious to get back to their hardscrabble farms in the New Hampshire Grants, the Green Mountain Boys gradually melted away. Benedict Arnold was wary. He was well aware of James Easton’s treachery and wondered what Allen might do next. The power struggle between them came to a head on June 10, 1775.

Among the Patriots and especially in the mind of Ethan Allen, the ease with which the forts at the south end of Lake Champlain were seized created what turned out to be overly optimistic expectations of ejecting the British from not just Lake Champlain but all of Canada. Allen believed himself to be just the man to lead such an expedition and decided to journey to Philadelphia and make his case before the Continental Congress. He was aware of how James Easton’s appearance before the Massachusetts authorities had shaped public perceptions of the capture of Ticonderoga and created problems for Benedict Arnold. A personal appearance in Philadelphia, he reasoned, might bring a favorable result for his cause. So on June 10, while Arnold was out on the lake with the American fleet on reconnaissance, he convened a council of war at Crown Point, Major Elmore of Connecticut, presiding. The resolution’s language endorsed Ethan Allen’s personal conduct: “Colonel Allen has behaved, in this affair, very singularly remarkable for his courage, and must, in duty, recommend him to you and the whole Continent.”[8]

Seventeen officers, including Colonel Easton, were present and readily endorsed the resolution. Allen would carry it with him to Philadelphia along with a petition signed at Crown Point by 500 citizens and soldiers requesting that he be allowed to brief the delegates.

In the late afternoon, as the sloops Enterprise and Liberty returned from the reconnaissance sortie and dropped anchor off Crown Point, Arnold learned of the council of war, still in session. The convoy’s crews were kept on station as he was oared to shore. He was livid, but chose not to appear at the meeting, believing the officers involved might be conspiring to arrest him. Per the Regimental Memorandum Book:

At 4 AM Weighed Anchor & Beat up & at 5 PM Arrived at Crown Point where I went on shore & found that Colonel Allen, Colonel Easton and Major Elmore had Called a Council of their officers and others not belonging to My Regt. I sent for Major Elmore, who excused himself. On which I wrote the council that I could not, Consistently with my Duty, Suffer, any Illegal Councils, Meetings, etc., as they Tended to raise a mutiny. That I was at present the Only Legal Commanding Officer & should not suffer my Commands to be Disputed, but would willingly give up command whenever anyone appeared with proper authority to take it ___ this had the Desired Effect and they Gave up their Expectations of Commanding.[9]

Arnold then returned to the Enterprise for the night. The following morning, he aggravated the senior officers by preventing them from boarding one of the sloops.

Went on shore early & gave Orders to have the Guards Doubled, to prevent any Mutiny or Disorder, Colo. Allen, Major Elmore, Eason & others Attempted Passing the Sloop without showing their Pass & were brought to by Capt. Sloan & Came on Shore[10]

He again summoned Major Elmore to demand an explanation of the council of war and perhaps in hopes of using him as an intermediary in the dispute with Allen. This time Elmore, the senior officer from Connecticut on the scene, agreed to come. News had reached the lake that Connecticut’s Col. Benjamin Hinman at the head of a 1,000-man regiment was en route with orders to supersede Arnold and take charge. Elmore, slated to be his second in command, was already at Crown Point with an advance party of four companies. We can only speculate as to the dialog between them. Elmore, a fifty-five-year-old veteran of the previous war known as a free and familiar officer, likely tried to diffuse the situation and calm the volatile Arnold. Suddenly, a very angry James Easton burst into the room. What was said is not recorded, and we have only the Regimental Memorandum Book version of what took place. Arnold wrote, with evident relish:

when in Private Discourse with Elmore, Easton, Intruded, & Insulted me, when I took the Liberty of Breaking his head, & on his refusing to Draw like a Gent’n He having a hanger by his side & Case of Loaded Pistols in his Pocket, I kicked him very heartily __& Ordered him from the Point immediately.[11]

By issuing a challenge to Easton in this manner, in the presence of a fellow officer no less, Arnold turned their animus into an affair of honor. In the era, to back down from such a challenge was considered cowardly, shameful behavior unbecoming of a gentleman. Along with Major Elmore, others were evidently present and word of the episode spread far and wide among the officer corps on Lake Champlain. Though he continued in service, the damage to Easton’s reputation would be deep and long lasting.

Whispers behind his back and a notable humiliation followed. New York’s Gen. Philip Schuyler, in command of the Northern Department of the Continental Army, administered a clear reprimand during the mobilization for the Canada expedition in the summer of 1775. Crown Point, fifteen miles north of Ticonderoga, was the primary embarkation base for the American expedition, It hummed with frenetic activity under the command of Major Elmore. To better oversee preparations, Schuyler relocated his headquarters from Albany to Fort Ticonderoga, arriving July 17. That day, he issued the first in an unrelenting stream of detailed orders for Crown Point. Correspondence between them reveals that Elmore overcame Schuyler’s well-known prejudice against military men from Connecticut and managed to establish himself as a reliable officer in the eyes of the general.

On August 17, as the planned date of the embarkation drew close, Schuyler left Ticonderoga briefly for a council meeting in Albany with Mohawks and other members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. During his absence, Colonel Easton persuaded the temporary commander, Gen. Richard Montgomery, to send him from headquarters to the Point and assume command as senior officer, superseding Major Elmore. Montgomery, new to colonial service, was evidently unaware or indifferent to the incident at Crown Point.[12]

On his return a few days later, Schuyler summarily countermanded Montgomery’s directive and reappointed Elmore to the command. Colonel Easton was ordered to ride with all dispatch to Ticonderoga immediately upon receipt of the order. To drive home the general’s annoyance, Easton’s men at the Point were also recalled. They were required to march the fifteen miles to Ticonderoga instead of taking the preferred waterborne route. To expedite matters, they were to depart the following day and leave their baggage behind. It would follow later—by bateaux.[13] Easton’s regiment would subsequently be held back, assigned continued garrison duty at Fort Ticonderoga and miss out on the launch of the expedition. It would be much later that fall when manpower needs became overwhelming that Schuyler finally relented and dispatched the Massachusetts men northward.

Behind the scenes, sniping at Easton among the officer corps is known to have occurred. In October, during the siege of Montreal, Maj. Henry Livingston of New York’s 3rd Regiment wrote to a friend, “The General [Montgomery] acquaints me that we must stay here for some time & then go in a body of men who he is giving to send with Cannon to Montreal, & tells us that probably Coll. Easton will command the party—This circumstance is unpleasing to our officers as they have heard that Easton is a good deal of an old woman & has been xx on the parade at Ticonderoga by Col Arnold.”[14]

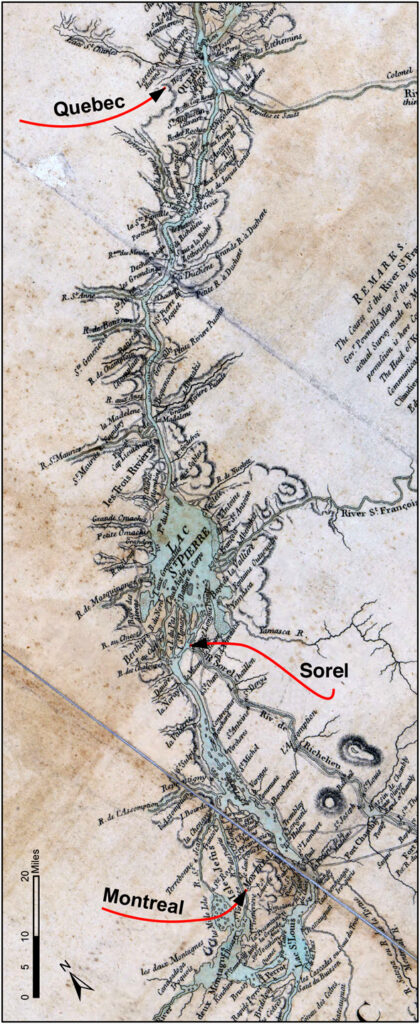

The incident which provided Benedict Arnold with a golden opportunity to further tarnish Easton’s reputation and put his career in jeopardy occurred during the Canada Expedition on the St. Lawrence River in the aftermath of the surrender of Montreal. While Montgomery’s battalions were engaged in the capture of Montreal, Arnold was nearing Quebec City at the head of about 700 tattered and worn-out Colonials. Back in early September, he had traveled to Boston looking for a command and persuaded George Washington to support a second expedition against Canada’s lightly-garrisoned capitol. Arnold led his detachment up an eastern route beginning at the mouth of Maine’s Kennebec River and on November 13 arrived at the St Lawrence River before Quebec. There he awaited General Montgomery’s army.

Governor General Guy Carleton had traveled from Quebec in order to personally direct the British and Canadian defense forces at Montreal. Upon arrival in early November, Montgomery’s American expeditionary force methodically encircled the city. Montreal’s seigniors and prominent citizens had agreed among themselves to relinquish the city to the Americans without a fight. A small flotilla of transports and an escort comprised of the brig Gaspée and four armed schooners was assembled on the river. Carleton believed it best to gather the available military stores and fall back to make a stand at Quebec City. At dusk on November 11, he embarked with a contingent of regulars and 140 women and children. The squadron encountered bad weather, dangerous shoals and contrary winds, allowing them to advance only about thirty miles toward Quebec City.

General Montgomery had anticipated Carleton’s move and stationed a detachment under Colonel Brown and the remnants of Colonel Easton’s command—about two-hundred men—at Sorel, near the mouth of the Richelieu River. Their orders were to intercept the flotilla and prevent the provincial governor from reaching Quebec City. A six-cannon artillery emplacement of 12-pounders and two gun boats at a narrow portion of the river was judged sufficient to prevent the escape. A second battery was then established nearby comprised of three 12-pounders and a 9-pounder. Colonel Easton’s contingent was “half naked” and rife with the homesickness “virus”. In order to give his soldiers an incentive to stay in place, he prevailed upon the general to make an unusual offer. As Montgomery later explained in a letter to General Schuyler, he “ventured to go beyond the Letter of the Law. . . . By way of Stimulant, I offered as a Reward all public Stores taken in the Vessels, to the Troops who went forward, Except Ammunition and Provisions.”[15] Montgomery also called on Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys and units of Timothy Bedel’s New Hampshire Rangers to rush to the scene as reinforcements. Only a gondola mounted with a 12-pounder manned by twenty-five of Bedel’s Rangers appeared. Seth Warner ignored Montgomery’s order—he had no interest in coming to the aid of Ethan Allen’s arch-nemesis who at that point was expected to arrive at Quebec any day. Benedict Arnold was on his own as far as he was concerned. The Boys’ enlistments were up; they headed home.

Montgomery’s offer was atypical for a combat operation on an inland body of water but not necessarily out of line or illegal. Under maritime law of the era, hostile merchantmen and warships captured on the high seas were routinely taken as prizes to the nearest friendly port, condemned by the authorities and auctioned off. Proceeds were then divided among the officers and crew of the victors by rank according to a set formula. Fortunes were made by American privateersmen in this way during the War of Independence. On the St. Lawrence that November, the exigencies of the conflict precluded a pause for a legal proceeding.

Following a scouting foray to the area by some of Carleton’s boats, the volume of fire from the Colonial’s artillery convinced the British to withdraw upstream to consider their options. It was deemed too risky to challenge the blockade with the high-ranking personage of the governor general aboard. The Loyalist cause would suffer irreparable harm if he were to be captured. Instead, the council agreed he should attempt his escape in a rowboat, disguised as an Indian. In the dead of night, a select crew pulling on muffled oars carried him through to safety. It was an embarrassment. Given the opportunity to capture the highest-ranking leader of the king’s government in Canada, Easton and Brown failed to post adequate sentries and allowed Guy Carleton to slip through their fingers.

But all was not lost. Following Carleton’s escape, the commander of squadron, Gen. Richard Prescott, agreed to open surrender negotiations with the Americans. Envoy Colonel Brown met with Prescott and cleverly exaggerated the number of cannon positioned downriver. He convinced the British commander that any attempt to run the gauntlet would be futile and result in unnecessary bloodshed. By the time Articles of Capitulation were signed and the Americans boarded the ships, all the powder and shot had been dumped in the river, contrary to the terms of the capitulation. However, about a thousand barrels of provisions remained. General Prescott and one hundred seamen and soldiers were taken captive.

With Montreal under American control and the British flotilla in hand, an expeditionary force for the march on Quebec was assembled. James Easton could not stomach personal involvement in a rescue of his archrival Benedict Arnold, much less the prospect of serving under him, so he decamped—just as he had done after the capture at Ticonderoga. In late November, he took leave of his 150 men. Transferring them to Lieutenant-Colonel Brown, he departed via the Richelieu River and headed southward, ostensibly to raise bounty money for a renewed recruitment campaign and coincidentally to disseminate his version of what took place at Sorel. Avoiding his nemesis Arnold came at a price. He was not on the scene to oversee an inventory of the captured provisions or preserve his claim.

Nearly three months later, upon learning of Montgomery’s irregular authorization and hearing tales of looting aboard the captured fleet, Benedict Arnold pounced. Writing a letter to the President of the Continental Congress from Quebec, dated February 1, 1776, he alleged that Brown and Easton “had been publickly impeached with plundering the officers’ baggage taken at Sorel, contrary to the articles of capitulation, and to the great scandal of the American Army.”[16] Months later, an investigative committee appointed by Congress reported on July 30, 1776, “that in the course of their inquiries they had reason to believe that General Prescott’s baggage was plundered by some licentious persons in violation of the faith of the capitulation.” and that General Schuyler “be desired” to organize a court of inquiry as soon as possible—a request Schuyler studiously ignored.[17]

Was there truth to the allegation? In the era, the line between public and personal property in these circumstances was not always well-defined. Baggage and personal property of commissioned officers was considered inviolable. In practice, that of enlisted men and sailors, less so. It is probable that in the confusion and excitement of the moment, improper individual takings occurred.

Evidence of at least two instances of plunder survives. 1st Lt. Martin Johnson of Lamb’s independent New York Artillery company admitted to taking a diamond ring belonging to Capt. William Anstruther of the 26th Regiment, but denied having opened his personal baggage.[18] Second, a sergeant of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, coincidentally also named John Brown, sent a petition to General Schuyler to humbly request reimbursement for a detailed list of articles taken from him at Sorel. It included bedding, furniture, clothing, five guineas cash, and a silver-mounted sword. He valued the items at a “best estimate of forty pounds sterling” and concluded his plea to the general with: “That if your Goodness would be pleased to take Your Petitioner’s Loss into Consideration, it will be the means of saving a family from Ruin, and Your Petitioner shall be ever bound to pray for You.”[19] If Schuyler responded to the sergeant, there is no record of it in his papers.

Once Arnold’s allegation became public, Easton sought a venue for a court-martial to clear his name and put forward his claim for just compensation. He and his troops had been promised plunder and their leader was dead set on collecting it.

Barring special circumstances, courts were typically convened in the location where any alleged incident of misconduct occurred—access to witnesses being an important consideration. By the time the charges were raised the following spring, General Montgomery, who had regarded him favorably, had been killed in December’s failed assault on Quebec. The newly-promoted Gen. David Wooster turned him down. Benedict Arnold, now the field officer in command of the theater where the incident occurred, would have denied him out of hand. Finally, Philip Schuyler declined to get involved, calling a court martial “inexpedient.”

For his part, Lt. Col. John Brown, in a petition to the Continental Congress, recounted his frustration attempting to get the various generals to convene a court of inquiry—Arnold, Wooster and Schuyler had all denied him as well—and named Arnold and his followers as instigators of the charges. He labelled them “false, scandalous, and malicious; and your petitioner desires men and angels, as well as the informer, to prove any part of it.”[20] In contrast to Easton, Brown focused on reinstatement as an officer in good standing, and let the plunder claim drop. Eventually, both men were allowed to remain in service and receive pay as colonels, pending resolution of the matter. Brown continued to serve, including a stint as major in Col. Samuel Elmore’s Connecticut Regiment in 1776 and 1777, while making further attempts to clear his name. He eventually left the service of his own volition, without resolving the matter.

Easton doggedly continued to seek a command, but was denied at every turn. He seemed oblivious to the stigma he carried. In desperation, he wrote to Commander-in-Chief George Washington, who replied that any appointment would have to be made in Canada. That April, he journeyed to Philadelphia and filed a petition to congress for reimbursement of personal expenses incurred during the northern campaign, the convening of a court of inquiry for reinstatement and the appointment of a commission to determine the value of the public stores taken at Sorel. They “recommended to the general commanding in Canada, to estimate all the public stores taken with General Prescott and pay the value thereof among the officers and men employed in that service, in such proportions as the commissioners shall determine.”[21] Congress also referred the requests for expense reimbursement and the convening of a court of inquiry to the Commissioners in Canada. Led by Benjamin Franklin, they were soon to depart Montreal, overburdened with other matters and did not respond.

To make matters worse for Easton, he was confined for several months in Philadelphia’s debtors prison for non-payment of a £1,500 obligation. Writing to John Hancock on May 8, he disclosed that he owed a further £900 to other creditors. He pleaded to be released to pursue settlement of his regimental accounts, asserting that from the prizes taken at Sorel he was owed a share of “1,835 Barrels of provisions, including 365 Firkins Butter at 60/p Barrel amounting to £5,505.”[22] The following November, Congress left it to General Schuyler to issue a warrant for payment of the participants as he saw fit. He had already indicated to Congress that it was impossible so long after the fact to create an inventory or list of shareholders. The matter was left unresolved and it appears none of the participants ever received any compensation.

The grudge match between Easton and Arnold finally came to a resolution with Easton’s dismissal from the service in 1779. In the end, whether the allegations were true or not, Benedict Arnold—who one year later would become the most infamous traitor in American history—had artfully settled the score with one of his foremost antagonists, a man whom he cast as a dishonorable coward.

[1] J. E. A. (Joseph Edward Adams) Smith, The history of Pittsfield (Berkshire County), Massachusetts (Boston: Lee and Shepard 1876), 203-204.

[2] Edward Mott to the Provincial Congress, Shoreham, May 11, 1775 in Bulletin of Fort Ticonderoga Museum (BFTM), Vol. IV, No.3 (January 1937): 58-59. “I went out with him for the town of Jericho where Col Easton raised between Forty and fifty men.” Accounts vary as to the actual number. The generally accepted roster of participants on May 10 at Hand’s Cove as compiled by historian Robert O. Bascom credits only eleven men to Massachusetts. In “Ethan Allen’s Men,” BFTM, Vol. II, No. 1 (January 1930): 9-13. A separate account written in 1876 sets the number at forty-seven men raised at Jericho and Williamstown, Massachusetts.

[3] “Benedict Arnold’s Regimental Memorandum Book. Written While at Ticonderoga and Crown Point in 1775,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 8, No. 4 (1884): 367. This entry is missing from the original held at Fort Ticonderoga Museum: Military Record MS.7160, June 10 and 11, 1775.

[4] Benedict Arnold (attributed), “The Veritas Letter,” Peter Force, American Archives (AA) Series 4, 2:1086-1087.

[5] Allen French, The Taking of Ticonderoga In 1775: the British Story; a Study of Captors And Captives (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1928): 31. The author investigates elements of the traditional story by comparison of the various contemporary accounts, taking into consideration Lieutenant Feltham’s report to his superiors and the personal biases of Arnold, Allen and others.

[6] Arnold, “The Veritas Letter,” 1087.

[7] Wiliam Delaplace, Hartford, July 28,1775, AA, Series 4, 2:1087.

[8] Ethan Allen et.al. to Continental Congress, AA Series 4, 2: 957-958.

[9] “Benedict Arnold’s Regimental Memorandum Book,” 373.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Philip John Schuyler, Orderly Book of June 28, 1775 – April 18, 1776, New York, Fort Ticonderoga, Albany, Fort St. George, Huntington Library, San Marino, California, mssHM 663, No. 290:107, hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll7/id/23770/rec/12.

[13] Ibid., No. 315, 316: 113.

[14] Major Henry Livingston to Colonel James Clinton, Laprairie, October 22, 1775, New York Public Library Microfilm Collection, www.henrylivingston.com/writing/letters/tocolclinton2-75.htm.

[15] Richard Montgomery to Philip Schuyler, Holland House, Heights of Abraham, December 5, 1775 in William Bell Clark, Ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1966), 2:1277.

[16] Benedict Arnold to Continental Congress, Quebec, February 1, 1776, AA Series 4, 4:907-908.

[17] Journal of the Continental Congress (JCC), July 30, 1776, AA Series 5, 1:1594.

[18] JCC, August 17, 1776, AA Series 5, 1:1611.

[19] Petition of Sergeant John Brown of the Royal Artillery to Philip Schuyler, Undated, Philip Schuyler Papers 1776, New York Public Library: 907-908, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/93648550-4df2-0134-3ed3-00505686a51c.

[20] John Brown Petition to the Continental Congress, June 26, 1776, AA Series 5, 1:1219-1220.

[21] JCC, April 26, 1776, 4:313-314.

[22] James Easton to John Hancock, May 8, 1776, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 4:1461-62.

One thought on “James Easton vs. Benedict Arnold: Anatomy of a Feud”

To the Editor:

I greatly enjoyed Mr. Elmore’s article about the relationship between James Easton and Benedict Arnold, but I have to disagree with his characterizations of Arnold’s behavior and motives. Mr. Elmore calls Arnold “vindictive”, but the facts suggest otherwise.

After the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Easton requested a promotion from Arnold, who naturally refused, considering that Easton had shown personal cowardice in the initial assault and a lack of leadership in allowing the troops (including men ostensibly under Easton’s command) from plunder. Though Easton might have been “shocked” when Arnold refused him, no one else should have been.

In the subsequent physical confrontation between Arnold and Easton, Mr. Elmore casts Arnold as the provocateur, who “turned their animus into an affair of honor,” but it seems that Easton was clearly escalating the conflict and provoking a confrontation. Easton barged into a superior officer’s office, without permission, armed with a gun and sword, following numerous incidents of insubordination, including refusing to give a password to a guard, issuing orders to soldiers who weren’t under his command, and appearing drunk on duty. If Arnold was vindictive and intent on ruining Easton’s career, he could have had Easton court martialed right then. Instead, he settled the issue on a personal level and, while he might have relished kicking Easton’s ass, he seems to have quickly moved on to more pressing matters – like defending his country. This would seem more like a reflection of Arnold’s political naiveté than personal animus.

During the invasion of Canada, it was my understanding that, rather than ‘favorably regarding’ Easton (and his sometime colleague John Brown), Montgomery complained of their behavior in more than one incident and that it was Montgomery who had initiated the charges of plunder against them. By the time Arnold assumed command following Montgomery’s death, Easton was long gone, having left the expedition immediately after the capture of Montreal, and Arnold merely let the charges against him stand. When asked his opinion of Easton, Arnold’s report was unfavorable, for obvious reasons, as any responsible commander’s would have been. This doesn’t seem like someone who was ‘holding a grudge’, ‘looking for an opportunity to ruin [Easton’s] career, or ‘waiting to pounce’, as the article states.

Indeed, everything I’ve read about Arnold’s command suggests that he was an extremely forgiving and sympathetic officer where his troops were concerned, commuting men’s sentences, requesting mercy for others, even personally paying for his troops’ food, accommodations, medical needs, and even their salaries when necessary. I suspect that Arnold’s later actions have made us see evidence of his character flaws, even when there were none. Since several other commanding officers (including Montgomery, Gates, and Schuyler) also found Easton’s merit lacking, it seems that Easton was the one causing the problems.

Sincerely,

Greg Miller