It is not often that one comes across inspiration for research from a trading card. But sure enough, when this author came across a card produced by Topps featuring John Adams, he was inspired. The card, part of a set commemorating Presidential connections to the game of baseball, mentioned how Adams had mentioned playing a game of “bat and ball” as a child.[1] Now, it appears the card was partially incorrect. The letter stating this does exist but was written to Adams’ dear friend Dr. Benjamin Rush, not to Dr. Benjamin West as the card states.[2] Nevertheless, the inquiry begins. What was John Adams’ relationship to the game of baseball, or sports in general?

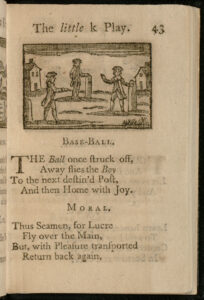

The earliest known reference to baseball in print occurred in 1744 in A Pretty Little Pocket Book, a children’s book printed in England; it was reprinted in America for the first time in 1783.[3] For one, this confirms that baseball’s origins are not wholly American. But it does show that it existed in some form during Adams’ lifetime. Another reference comes in the diary of a Princeton student in 1786.[4] These games likely looked different from our modern version of baseball but were still its ancestors. They were likely derived from games such as rounders or stool-ball.[5] It is hard to say when and where the modern game of baseball was truly invented, as claims range from Ancient Egypt to Medieval Europe to Colonial America.[6] Either way, a young John Adams evidently played some version of the game, displaying his athleticism while doing so.

When one thinks of our most athletic presidents, John Adams probably does not often come to mind. Famously short and stout, Adams was also known as being studious and rather stern. But as a young man, he was quite the athlete by his own admission. In that same letter to Dr. Rush, he wrote of “making and sailing Boats . . . Swimming Skaiting, flying Kites and shooting in marbles, Ninepins, Bat and Ball, Footbal . . . Wrestling and sometimes Boxing,” all as a young man playing truant from school.[7] It got to the point that he wrote of his father’s concern for his passion for sports instead of his studies.[8] Even as a young adult in 1759, he wrote of fond memories of his young sporting days.[9] It was not until he got to college that he wrotes of giving up his sporting ways in favor of studying.[10]

Even as an older man, Adams loved to use sporting metaphors in his writings. A 1782 letter to Edmund Jenings states, “Let Us keep up this Ball and Set all the litterary Sportsmen in Europe to play with it” in reference to trying to get foreign leaders to acknowledge American independence.[11] An 1811 letter describes the young United States as “a foot-ball between contending nations.”[12] So today when we refer to an idea as a “home run,” we can think back to how even John Adams used sporting metaphors as turns of phrase.

Adams also liked to acknowledge sports a feature of celebrations. On July 3, 1776, the day after what he considered to be the United States’ true Independence Day, and the day before what we now consider it to be, Adams wrote to his wife Abigail that American independence “ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”[13] While in France, he wrote of Sundays, “There are more Games, Plays, and Sports of every Kind on this day, than on any other, in the Week.”[14] Just as sports are considered leisurely activities today, so were they in the days of John Adams. He even wrote of watching his grandson, also named John, taking part in sports while his father John Quincy left the boy in his grandfather’s care.[15]

Nobody will ever mistake John Adams for American sporting legends such as Michael Jordan, Michael Phelps, or Willie Mays. Nobody will mistake him for the avid fans of sports that can now be found in his native New England. But what we see here is a much more human John Adams. A more relatable one. He liked sports, just as many of us do. He enjoyed them as leisurely or celebratory activities and recalled eschewing his studies in favor of them. There is something there that so many can now relate to. While we might view Adams as the stern old man in paintings, there was also a vibrant and athletic personality that he so deftly recalled in his own words.

[1] John Adams, Presidential Pastime. Topps.

[2] John Adams to Benjamin Rush, January 4, 1813, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5924.

[3] A little pretty pocket-book: intended for the instruction and amusement of little Master Tommy, and pretty Miss Polly: with two letters from Jack the giant-killer, as also a ball and pincushion, the use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good boy, and Polly a good girl: to which is added, A little song-book, being a new attempt to teach children the use of the English alphabet, by way of diversion. (Worcester, MA: printed by Isaiah Thomas, 1787), www.loc.gov/item/22005880/.

[4] Diary of John Rhea Smith, Nassau Hall, College of New Jersey. Princeton, 1786. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/exhibitions/baseball-americana/about-this-exhibition/origins-and-early-days/baseballs-roots/earliest-mention-of-baseball/.

[5] Library of Congress, “Origins and Early Days of Baseball,” Baseball Americana, www.loc.gov/exhibitions/baseball-americana/about-this-exhibition/origins-and-early-days/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “[Parents and Boyhood – from the Autobiography of John Adams],” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0002 .

[8] Ibid.

[9] “[Spring 1759 – from the Autobiography of John Adams] ,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-01-02-0004-0005-0001 .

[10] “[Parents and Boyhood].”

[11] Adams to Edmund Jenings, August 28, 1782, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-13-02-0165.

[12] Adams to Boston Patriot, June 27, 1811, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5651.

[13] Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-02-02-0016.

[14] Diary of John Adams, May 10, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0008-0004-0010.

[15] Adams to John Quincy Adams, September 8, 1820, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-03-02-3835.

2 Comments

I enjoyed your article. I’m a homeschooling mother who also volunteer teaches American Revolutionary War history to a class of 4-6th graders at our co-op. I love history, and I love our blustery, blunt, misunderstood Founder, John Adams! Your article made me think of David McCullough’s biography, “John Adams” wherein he describes how Adams was physically active into his very old age. He was a farm boy at heart. According to McCullough, Adams worked building stone walls, worked on his farm, and rode horses. Also, a letter Abigail wrote mentions seeing John working with a scythe with his hired hands in his fields. So I think you’re right that our stout and short founding father, while not as physically impressive as a Washington, was definitely a sturdy, active man. Thanks for the great article!

According to a post of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum’s Facebook page John Adams “was especially fond of wrestling because he believed it taught him self-discipline…A favorite target because he was a bit pudgy, Adams prided himself on his agility and the fact that he would never give up.”