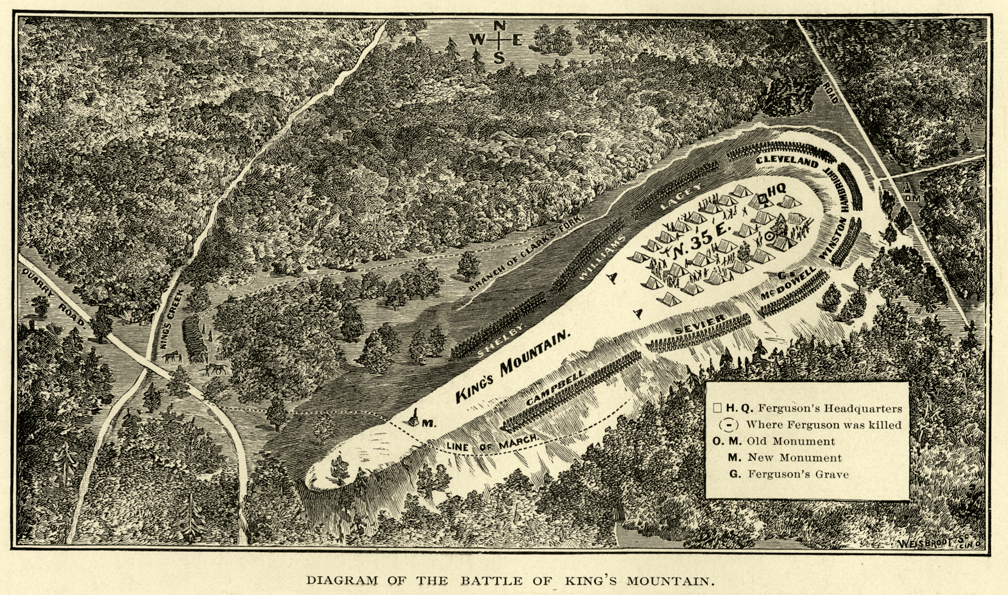

On January 4, 1881, historian James Watts de Peyster delivered an address to the New-York Historical Society in New York City. The lengthy oration dealt with the Battle of Kings Mountain, fought on October 7, 1780, in South Carolina, where the Revolutionaries achieved a decisive victory over a force composed of Loyalists. Although de Peyster raised several important questions about the battle, and his remarks were later published in pamphlet form, his work vanished into oblivion, perhaps due in part to the publication of Lyman C. Draper’s exhaustive study, Kings Mountain and Its Heroes, later that same year. Yet some of the issues that concerned de Peyster merit further inquiry, including the numbers engaged on each side, casualties, and the curious inactivity of six hundred Loyalist militiamen who were nearby but did not come to the aid of their comrades.

De Peyster may not have been an impartial researcher. He was a nephew of Capt. Abraham de Peyster of the King’s American Regiment, who was Maj. Patrick Ferguson’s second-in-command at Kings Mountain and surrendered to the Revolutionaries there. Although Captain de Peyster died more than twenty years before J. Watts de Peyster’s birth, the nephew very likely wanted to defend his late uncle’s reputation as both a Loyalist and an officer, since he devoted a portion of his address to defending the Loyalists’ military service during the Revolution.[1]

Noting that “the Americans have had pretty much the full say” in describing events at Kings Mountain, de Peyster sought to balance the narrative using “the accounts of three Provincial officers present, who survived the conflict.” These were Captain de Peyster, Lt. Anthony Allaire of the Loyal American Regiment, and Capt. John Taylor of the 1st Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers.[2] The historian de Peyster declared that he intended “to correct the mistakes into which the public have been led by a document, purporting to be a report” of the battle, an undated copy of which de Peyster found in the Horatio Gates Papers, housed at the New-York Historical Society.[3]

The document, undated and composed several days after the battle by American colonels William Campbell, Isaac Shelby, and Benjamin Cleveland, had been forwarded to the Continental Congress by Gates and was published in several newspapers, on the order of Congress, as the official report of the battle. It provided information on the numbers engaged along with the casualties on both sides.[4] De Peyster challenged the accuracy of the account, declaring that “this document, in my judgment, was not digested by the practical men who made the history, but was prepared by one experienced in such matters,” that is, propaganda, “and carries within itself conclusive evidence of this fact.” He also quoted Shelby’s later admission that the report was “nothing more than a brief and harried account in general terms of the expedition and the battle, drawn up to authenticate the intelligence of our victory and to give tone to public report.” Thus, de Peyster concluded that the document was primarily designed to shape “public opinion, to make military capital, and to satisfy the cravings of the Carolinian Whigs, famished by a series of defeats.”[5]

According to the allegedly “official” report, the Revolutionaries’ strength reported by their officers was 900, and the American commanders claimed to have found “provision returns” in the Loyalists’ camp that showed Ferguson had led 1,125 men. Of these, 19 of the provincial troops were reported killed, 35 wounded, and 68 captured; Loyalist militia casualties were given as 206 killed, 128 wounded, and 648 captured, a total of 1,104 (incorrectly stated as 1,105 in the document). American losses were reported as 28 killed and 62 wounded.[6]

These figures have been widely accepted for more than two centuries. Draper, who has been criticized as a “hero-worshiper” and “maker of heroes,” and who did not conceal his affinity for the “Overmountain Men” who lived west of the Appalachian Mountains and formed a large portion of the American force at Kings Mountain, nevertheless made a serious attempt to assess the strengths and casualties of the combatants.[7] Draper noted that the Overmountain Men spent the night of October 5 “making a selection of the fittest men, horses, and equipments for a forced march,” ultimately choosing about 700 while leaving some 690 “footmen and those having weak horses” to follow. Perhaps fifty of those on foot reached Kings Mountain in time to participate in the battle, Draper noted.[8] The next day, October 6, the Overmountain Men arrived at the Cowpens, where they were joined by four hundred North and South Carolinians under Brig. Gen. James Williams, bringing the total to eleven hundred, not counting the men on foot. From there, 910 men, again not including those lacking horses, were selected to continue pursuing Ferguson.[9]

As for the Loyalists, Draper asserted that “the exact strength of Ferguson’s force cannot with certainty be determined.” He mentioned the “official report” and its figure of 1,125, but noted, without giving a source, that there was “some reason to suppose that about two hundred Tories left camp that day, perhaps on a scout, but more likely on a foraging expedition.” That led him to assert, later in the volume, that “the Loyalist force under Ferguson at King’s Mountain was eight hundred.” Several pages later, however, Draper contradicted himself. He provided more detail on the two hundred-man foraging party, commanded by Col. John (or possibly Patrick) Moore, then declared that their departure from camp “would have left about nine hundred altogether . . . to fight the battle,” leading him conclude that “the numbers of the opposing forces were about equal.” Draper dismissed claims by Loyalist participants that Ferguson’s force had been outnumbered.[10]

Regarding American casualties, Draper repeated the figures of 28 killed and 62 wounded from the “official” report and remarked that these were “more reliable” than those stated by Isaac Shelby in a letter of October 12, 1780, in which Shelby mentioned 29 killed and 54 wounded and added that the numbers were more likely 35 killed and 50 to 60 wounded. Examining losses by unit, Draper did not find any sign of inconsistent reporting when he noted that the small number of militia from Lincoln County, North Carolina, “suffered considerably” while the much larger force of South Carolinians lost only their commander, General Williams, and one other man, both killed. Draper did find it “remarkable” that Col. William Campbell’s unit lost thirteen officers killed compared to only one enlisted man, but he claimed the disparity resulted from “how fearlessly the officers exposed themselves” during the battle. Draper attributed the Americans’ low casualties to the Loyalists firing too high, thereby often failing to hit the attackers.[11]

The exact losses among Ferguson’s troops “can only be approximately determined,” Draper stated. Campbell reported that 19 provincials were killed, 35 wounded, and 68 captured, with 206 Loyalist militiamen killed, 128 wounded, and 648 captured, a total of 1,104 casualties (Draper arrived at a sum of 1,103). Shelby’s October 12 letter gave a considerably lower figure of 1,016. Like de Peyster, Draper believed the discrepancy resulted from the American leaders’ wish to present Loyalist losses as “sufficiently large to make a decided impression on the minds of all classes, encouraging the friends of freedom, and equally depressing their enemies.” To support this assertion, Draper quoted Lt. Col. Henry Lee’s statement that “exaggeration of successful operations was characteristic of the times.”[12]

Later historians largely followed either Draper, the “official” report, or some combination of the two, thus minimizing the numbers and losses of the Revolutionaries while maximizing those of the Loyalists, as a look at some accounts of the battle demonstrates.

John S. Pancake, author of an influential 1985 academic history of the southern campaigns, gave figures of 910 Revolutionaries and over 1,000 Loyalists at Kings Mountain, with casualties of 28 killed and 62 wounded for the former and 157 killed and 163 wounded too badly to be moved for the latter. In a more recent academic work, Stanley D. M. Carpenter stated that 900 Revolutionaries and 1,000 Loyalists participated in the battle, writing that between 119 and 157 Loyalists were killed and 123 mortally wounded, while the Revolutionaries suffered “few casualties” because “the Loyalists consistently fired too high.” J. David Dameron’s volume, written for a popular audience, reports the Revolutionaries numbering 910 and the Loyalists between 1,075 and 1,125, with the Americans losing 29 killed, 4 mortally wounded, and 58 wounded and the Loyalists 244 killed, not including Ferguson, and 143 wounded. Dameron noted that Ferguson’s troops “did not have clear fields of fire.” The “Kings Mountain” page on the American Battlefield Trust’s website closely follows the “official” report, giving figures of 910 Americans who suffered 90 casualties and 1,125 Loyalists of whom 1,018 were killed, wounded, or captured.[13]

De Peyster challenged these statistics in his forgotten address. Basing his estimate on the statement in Allaire’s letter of January 30, 1781, which was later published in James Rivington’s New York newspaper, de Peyster insisted “that Ferguson went into action with about nine hundred men.” This did not match the number Allaire recorded in his diary entry for October 7, 1780, where he wrote that “Maj. Ferguson had eight hundred men.” Allaire added that there were 70 provincial troops present, though he did not indicate whether these should have been added to the 800. In his letter, however, Allaire stated that Ferguson commanded 800 militia at Kings Mountain along with 100 provincial troops.[14] Allaire was in an ideal position to know the strength of the Loyalist force, since he served as Ferguson’s adjutant, making him “responsible for the paperwork of the unit.” Loyalist Uzal Johnson of the New Jersey Volunteers, the provincials’ surgeon and close friend of Allaire—the two often collaborated when writing in their diaries—partially corroborated Allaire’s initial estimate when he gave a figure of seventy provincials at Kings Mountain in his entry for October 7. Although Johnson did not include a number for the militia, he wrote that “the Amn. Vols. charged them [the Revolutionaries] with success and drove them down the Hill, but were not able to pursue, our Number being so small” in relation to the attackers, but as with one of Allaire’s accounts, it is not clear whether Johnson was referring to the entire Loyalist force as “so small” or only the provincials.[15] Since Allaire and Johnson were in general agreement that their force numbered about nine hundred, that both Draper and de Peyster independently arrived at the same conclusion, and given the admitted tendency of victors to exaggerate their success by inflating the strength of the enemy, as well as the intent of Campbell, Shelby, and Cleveland to use their report to boost the Revolutionaries’ morale, it is safe to conclude that Ferguson commanded about nine hundred Loyalists at Kings Mountain.

After addressing the issue of Loyalist numbers, de Peyster turned his attention to those of the Americans, declaring that just as the size of Ferguson’s force had been exaggerated, that of the Revolutionaries had “been underestimated.” Dismissing the claims of Loyalist participants—Allaire claimed the attackers were 2,500 strong, and Taylor’s assertion that Ferguson’s force was outnumbered 4:1 would have translated to 3,600 Revolutionaries—de Peyster began his calculation of American strength with the accepted account that three thousand men from west of the Appalachians set out after Ferguson. Whereas Draper and most historians since stated that General Williams of South Carolina and Col. Frederick Hambright and Maj. William Chronicle of North Carolina joined the Overmountain Men before the force was winnowed to 910 men, de Peyster argued that these reinforcements joined only afterwards, and their numbers should be added to the 910. Williams’s 400 South Carolinians and the 60 North Carolinians would bring American strength to 1,360. Because Shelby stated that “Colonel McDowell’s command had been considerably augmented during the march,” de Peyster concluded that this was in addition to the reinforcement from the Carolinas, so “these accessions must have swelled the number to fifteen hundred at least.” In support of his assessment, de Peyster noted that in their postwar histories of the Revolution, Lt. Col. Henry Lee gave this figure, and Lt. Col. Edward Carrington placed the Revolutionaries’ strength at about sixteen hundred.[16] However, Lee and Carrington only served in the South later in the war; neither was present at King’s Mountain, although they undoubtedly drew some of their information from participants.

There is substantial evidence to support de Peyster’s belief that the American force was reduced to 910 before the Carolinians joined the Overmountain Men. The “official” report stated that after Williams with 400 men arrived at the Cowpens on October 6 and united with the Overmountain Men, the officers decided to pursue Ferguson with 900 of the “best horsemen.” Many participants contradicted that assertion. A veteran of the battle, North Carolinian William Lenoir, stated that when the American commanders realized that they would not catch Ferguson by pursuing with infantry, “orders were given for as many as had, or could procure, horses, to go in advance,” leaving those without horses to follow. Lenoir wrote that “about five or six hundred” mounted men set out at dawn on October 6, leaving fifteen hundred “footmen” to follow. During their march, the horsemen were joined by Williams, though according to Lenoir, Williams commanded only “a few South Carolina militia.” Another Kings Mountain veteran, Benjamin Sharp, was with the Overmountain militia and recalled afterward that they were “all mounted” and numbered between 1,500 and 1,800. “After hard marching for some time, we found our progress much retarded by our footmen and weak horses,” Sharp stated, and “it was then resolved to leave the footmen and weak horses . . . to follow as fast” as they could. Sometime after the reduced force of Overmountain Men reached the Cowpens, Williams arrived “with several hundred men.” It is notable that Shelby, who signed the “official” report declaring that the Carolina reinforcements joined the Overmountain militia before the 910 men were selected to continue the pursuit, contradicted that statement in an 1823 pamphlet. In an account that closely matched Sharp’s description of events, Shelby wrote that 910 Overmountain Men were selected on October 5, “started about light the next morning” to find Ferguson, and were later met at the Cowpens by Williams, “with about four hundred men.” Joseph Graham, a North Carolina officer who was not present at the battle but knew many of the participants, later wrote that the Overmountain colonels on October 4 “resolved, that they would select all the men and horses fit for service, and immediately pursue Ferguson”; the following evening, they chose 910 men and set off for Cowpens, where they were joined by Williams with almost 400 men and Hambright and Chronicle with an additional 60. Loyalist Alexander Chesney, who fought at Kings Mountain, wrote that “we were attacked before any support arrived by 1500 picked men . . . all of whom were armed with Rifles.”[17] Taken together, the accounts other than the “official” report indicate an American strength ranging from Lenoir’s 900 to 1,000 (if Williams’s 400 are added in place of the “few” militia Lenoir claimed Williams led), to 1,370 if the 460 Carolinians are added to the 910 Overmountain Men. Nevertheless, historians continue to accept the version of events in which the 910 Americans who fought at Kings Mountain were chosen after Williams and Hambright united with the Overmountain militia, rather than before the junction of the two forces.

Another approach to calculating American numbers, utilized by Lawrence E. Babits in his landmark study of the 1781 Battle of Cowpens, involves the use of federal pension applications. Babits noted the discrepancy between the Cowpens account of British commander Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, who claimed he was opposed by 2,000 Americans, and that of American commander Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, who reported his strength as just over 800. For more than two centuries, historians adhered to Morgan’s figure while vilifying Tarleton for exaggerating his enemy’s strength as a ploy to explain the British defeat. Babits identified about six hundred American veterans who, in applying for pensions decades after the battle, testified that they had fought at Cowpens. He observed that in cases where the size of a unit was known, “the pension application rate is less than one to three or four. That is, one pension application equaled at least three or four Cowpens soldiers—and this is a low figure.” Babits concluded from this analysis that between 1,800 and 2,400 Americans actually fought at Cowpens. Tarleton had been telling the truth.[18]

The same method can be applied to estimate the number of Revolutionaries at Kings Mountain. In 1990, historian Bobby Gilmer Moss published The Patriots at Kings Mountain, in which he identified more than seven hundred men who had participated in the battle. An examination of his sources shows that nearly six hundred soldiers were identified from their federal pension applications. Subtracting applications filed by family members after a veteran’s death, and those of men who were not actual participants (for example, Josiah Brandon fought under Ferguson and switched sides after the battle, while John Caruthers had been captured a few days earlier and escaped during the action) leaves a total of 439 men who, in filing for pension benefits, declared under oath that they had been present at the Battle of Kings Mountain. Nearly all were in combat; very few—one man sent to find horses, another who fell ill after reaching the field, a third assigned to guard baggage—did not fight.[19] Using the same methodology as Babits, the pension applications of Kings Mountain veterans clearly indicate that at least 1,300 Americans and as many as 1,750 fought in the battle.

De Peyster did not challenge the American casualty figures, but given Babits’ findings on Cowpens, the accepted numbers may not be accurate. While Morgan reported American losses at Cowpens as 12 killed and 60 wounded, Babits’s examination of pension records revealed the names of 24 killed and 104 wounded. Babits remarked that it was “unlikely” that Morgan “had accurate counts of the militia.”[20] Moss indicated in his compilation those soldiers who were killed or wounded, though he made no attempt to arrive at a total. Given the unreliability of figures for militia units, the loss of numerous officers, and the haste with which the Americans withdrew from Kings Mountain to avoid the possible arrival of a British relief force from Charlotte, North Carolina, only thirty-five miles from the battlefield, it is almost certain that no accurate accounting of casualties was undertaken. Loyalist doctor Uzal Johnson, who was forced to treat wounded Americans after the action, provided probably the best account. Johnson wrote in his diary that fifty of the provincial troops “got killed & wounded,” and that 225 Loyalist militiamen were killed and 72 wounded. “How many of the Enemy got kill’d is uncertain, not far inferior to ours if we judge from the Number of their wounded which was equal to ours, I being employed to dress them . . . enabled me to get the Number,” Johnson wrote.[21] The editors of Johnson’s diary note that his “figures for British casualties are higher than some consensus estimates . . . but he may well have been in the best position to know,” and that Johnson’s calculation of American losses was “also higher than most conventional estimates, but official reports from both sides often omitted the militia.”[22] If, as Johnson asserted, the number of wounded on both sides was equal, that would mean about 100 Americans were wounded, and while his estimate of American killed, about 250, is undoubtedly high, it would still be significantly larger than the thirty or so given in most accounts. The disparity, as noted earlier, is usually attributed to Ferguson’s men firing too high, but the Loyalist militiamen were experienced backcountry hunters and many had served alongside the Revolutionaries in the 1776 campaign against the Cherokee, so there is little reason to believe that their marksmanship was not on a par with that of their opponents. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, in assessing British strength in South Carolina in August 1781, commented that the British had nearly one thousand Loyalist militia with them, and that “the militia Tories from their being such exceeding good marksmen, will not be the least useful” of the British force.[23] Draper agreed, writing that the Loyalists at Kings Mountain, like their opponents, “were expert riflemen.”[24] If the Revolutionaries’ casualties were lower than those of the Loyalists, the difference was probably less than most accounts state, and more likely the result of Chesney’s observation that the slopes of King’s Mountain were “covered with wood which sheltered the Americans” rather than the Loyalists’ poor marksmanship.[25]

Another point de Peyster raised and termed one of Ferguson’s “grievous mistakes” was making “an eccentric retreat which is inexplicable,” when the Loyalists could have marched directly to join Lord Cornwallis’s army in Charlotte. De Peyster suspected that Ferguson “may have been led to this last and fatal course by assurances of support which were not fulfilled. It is well known that there were six hundred Tories in arms within a few miles of the scene of his disaster, whose assistance might have converted it into a victory.” These Loyalists “did not put in their appearance,” and de Peyster angrily added that “it is to be hoped that they suffered due punishment for their delinquency.” He also suggested that if the Loyalists, who were camped “within a few hours’ march to the west,” had come to Ferguson’s aid, they could have “stampeded their [Americans’] horses and fallen upon their rear, the result would have been . . . fatal.” The Revolutionaries were so preoccupied with Ferguson’s troops in their front that “one hundred to one a fire in the rear would have made them skedaddle,” de Peyster declared.[26]

Draper, too, noted the presence of the Loyalist militia not far from Kings Mountain, and speculated on their failure to join the action. Draper remarked that in their pursuit of Ferguson, the Revolutionaries “passed where several large bodies of Tories were assembled; one, numbering six hundred, at Major Gibbs’, about four miles to the right of the Cowpens, who were intending to join Ferguson the next day.” Later, he wondered why many high-ranking Loyalist militia officers were not with Ferguson. “It is not a little singular, that so few of the prominent Loyalist leaders, of the Ninety Six district, were with Ferguson,” he remarked, naming among others “Colonels Cunningham, Kirkland, and Clary” along with Gibbs, as notably absent. “Some were doubtless with the party whom the Whigs had passed at Major Gibbs’ plantation,” and others were elsewhere in the vicinity of the battlefield, “but they were not at King’s Mountain, when sorely needed, with all the strength they could have brought to the indefatigable Ferguson,” Draper remarked. While conceding that “the Loyalists evinced no little pluck and bravery at King’s Mountain,” he implied what he believed to be the reason for the nearby Loyalist militia’s failure to join Ferguson, quoting Thomas Paine’s American Crisis wherein Paine alleged that “every Tory is a coward, for a servile, slavish, self-interested fear is the foundation of Toryism; and a man under such influence, though he may be cruel, can never be brave.”[27]

The reason for the Loyalist militia’s not marching to Kings Mountain was not cowardice, as is clearly shown in letters that Ferguson wrote to militia major Zacharias Gibbes shortly before the battle. Gibbes, an ardent Loyalist, was certainly no coward. He had fought the Revolutionaries at Ninety Six in 1775, was captured after the Battle of Kettle Creek in 1779 and sentenced to death but was instead banished, and then took the field after the British captured Charlestown in May 1780.[28] Gibbes included Ferguson’s letters in his postwar claim for compensation, and the documents appear to have thus far escaped the notice of historians. On October 5, Ferguson, who was at “Buffaloe Creek within 3 Miles of Cherokee ford,” addressed a message to Gibbes “or any other Officers of his Regt.” After describing his location, Ferguson instructed the Loyalist officers

to send any reinforcements that are marching to join me to thicketty, where they will inform themselves of my Situation & join me. Lose no time. If I should move to any other Side of The Country, so as to make it unsafe for to come to Camp by Cherokee ford, I will give Notice. Please to inform the Comg officers of Companys of your Regts of this & also send a Copy to a Captn. of Plummers to be sent round to the officers of that Regt: In case of accident the officers need not publish this, or snares may be laid for them on the road. those who march should have two or three men always advanced & one or two push’d out on each flank. they should not keep the road if they Suspect an Enemy, always advance impudently, under Cover of the woods so as not to show their numbers, upon any Enemy in their way, & at night lodge themselves in a Log house & have their knives ready.

Beneath his signature, Ferguson added: “If your People have any inclination to settle their country speedily there never was Such an opportunity if they are not expeditio[us] it will be too late & your District will be over run.”[29]

Later that day, Ferguson sent Gibbes a second message. The note stated: “Sir I am now on my march to [illegible word] near King’s Mountain. I wish not to have any reinforcements from you immediately as they may be Destroyed on their way. take Care of yourself—for some Days—Sumpter & Clark have joined Macdowal.”[30] This previously unreferenced correspondence clearly explains why Gibbes and the Loyalist militia did not march to Ferguson’s assistance. After originally ordering the militia to join him, Ferguson reconsidered and, believing that the danger to the militia was too great, canceled his earlier instructions. Perhaps Ferguson recognized that he was in a difficult position and knew that if his force were to be overwhelmed, keeping the remaining Loyalist militia intact would be essential to maintaining British control in the South Carolina backcountry. On the other hand, Ferguson may have concluded that he did not need the militia’s aid and chose not to have them undertake a risky march through a region swarming with Revolutionaries. Whether it was for these or other reasons, the Loyalist militia cannot be accused of cowardice or neglect of duty. They followed the orders of their superior. Had the officers chosen, on their own, to march to Kings Mountain, there is no guarantee they would have altered the battle’s outcome, de Peyster’s claims notwithstanding.

Although much of de Peyster’s address dealt with issues of personal concern to him, particularly as they related to his ancestor, he called into question many generally accepted aspects of the Battle of Kings Mountain. Examining the issues he raised concerning the strength and casualties of the opposing forces reveals that the Loyalists were somewhat fewer in number than believed, while the Revolutionary force was far larger than usually stated. Also, American casualties were likely somewhat higher than the traditionally accepted figure. Finally, de Peyster’s criticism of the Loyalist militia’s failure to join Ferguson can be answered through other forgotten documents: Ferguson’s two letters enclosed in Gibbes’ Loyalist claim. Taken together, the analysis of issues discussed in the neglected work of de Peyster and the information contained in Ferguson’s overlooked correspondence provide important new insights into the campaign and Battle of Kings Mountain.

[1] J. Watts de Peyster, “The Battle or Affair of King’s Mountain, Saturday, 7th October, 1780,” microfiche, David Center for the American Revolution, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA, 1, 2.

[2] Ibid., 4.

[3] Ibid., 1.

[4] The document, labeled “Official Report,” is reproduced in Lyman C. Draper, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of Kings Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events Which Led to It, reprint edition (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2002), 522-524.

[5] De Peyster, “King’s Mountain,” 1-2.

[6] “Official Report,” in Draper, King’s Mountain, 521-522.

[7] William B. Hesseltine, “Lyman Draper and the South,” Journal of Southern History 19 (1953):20.

[8] Draper, King’s Mountain, 221-222, 221n.

[9] Ibid., 226-227.

[10] Ibid., 237-238, 293, 297-299, 298n.

[11] Ibid., 279, 302, 305.

[12] Ibid., 297, 300-302.

[13] John S. Pancake, This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985), 117, 118, 120; Stanley D. M. Carpenter, Southern Gambit: Cornwallis and the British March to Yorktown (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 125, 126, 127, 128; J. David Dameron, King’s Mountain: The Defeat of the Loyalists, October 7, 1780 (New York: Da Capo Press, 2003), 46, 49, 51, 76, 80; “Kings Mountain,” American Battlefield Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/kings-mountain.

[14] De Peyster, “King’s Mountain,” 5; Lt. Anthony Allaire to unnamed, January 30, 1781, in Draper, King’s Mountain, 516-517; Anthony Allaire, Diary, October 7, 1780, in Draper, King’s Mountain, 510.

[15] Uzal Johnson, Captured at Kings Mountain: The Journal of Uzal Johnson, a Loyalist Surgeon, eds. Wade S. Kolb III and Robert M. Weir (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2011), xiii-xvi, 31.

[16] De Peyster, “King’s Mountain,” 4, 5.

[17] “Official Report”; William Lenoir, “An Account of the Battle of King’s Mountain,” Benjamin Sharp, “Battle of King’s Mountain,” Isaac Shelby, “Battle of King’s Mountain,” Joseph Graham, “Battle of King’s Mountain,” all in Draper, King’s Mountain, 522, 548, 552, 555, 565; Alexander Chesney, The Journal of Alexander Chesney, A South Carolina Loyalist in the Revolution and After, ed. E. Alfred Jones, The Ohio State University Bulletin 26 (1921):17.

[18] Lawrence E. Babits, A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 150.

[19] Bobby Gilmer Moss, The Patriots at Kings Mountain (Blacksburg, SC: Scotia-Hibernia Press, 1990).

[20] Babits, Devil of a Whipping, 151, 152.

[21] Johnson, Captured at Kings Mountain, 31.

[22] Ibid., 110n.

[23] Nathanael Greene to George Washington, August 6, 1781, in Dennis M. Conrad, ed., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 9 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 139-140.

[24] Draper, King’s Mountain, 294.

[25] Chesney, “Journal,” 17.

[26] De Peyster, “King’s Mountain,” 5, 6.

[27] Draper, King’s Mountain, 222-223, 294.

[28] Zacharias Gibbes, Loyalist Claim, 1783, Great Britain Audit Office (AO) Papers 12/46/145-146, microfilm, David Center for the American Revolution, American Philosophical Society.

[29] Patrick Ferguson to Zacharias Gibbes, October 5, 1780, in Gibbes, Loyalist Claim, September 12, 1783, AO 13/119/155.

[30] Ferguson to Gibbes, October 5, 1780 (second letter of this date), in Gibbes, Loyalist Claim, AO 13/19/155A.

3 Comments

Fantastic article!

Great information and fantastic article!

Hi Mr. Piecuch, Thanks so much for your excellent and intriguing discussion.