James Craik was born in Scotland, circa 1727, on the 1,400-acre estate of his father William Craik, member of the British parliament. He attended Edinburgh medical school; the first medical school in the English-speaking world. After graduation Dr. Craik served in the British army in the West Indies. Leaving the army, he set up medical practice in Norfolk, Virginia, then moved to Winchester, the most remote town on the Western frontier. For nearly half a century, Dr. Craik devoted much of his life to serving George Washington as personal physician and confidant, as well as his “compatriot in arms and old and intimate friend.”1 “If I should ever have occasion for physician or surgeon,” wrote Washington in 1798, “I should prefer my old surgeon Doctor Craik, who from 40-years’ experience, is better qualified than a dozen of them put together.”2

In 1753, twenty-one-year-old George Washington was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Virginia Regiment, with orders to lead an expedition to demand the French vacate their forts and withdraw from the Ohio River valley. Dr. Craik rejoined the military, with the rank of lieutenant, to serve as surgeon with the regiment. On July 3, 1754 the French attacked Fort Necessity to start the French and India War. During the battle, reported Washington, “Our sick and wounded were left with a detachment under the care and command of the worthy Doctor Craik . . . surgeon to the regiment.”4

Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock, with one thousand professional British troops, arrived in Virginia on February 20, 1755 to drive the French out of the Ohio River Valley. Braddock led his red-coated regulars and colonial troops to attack Fort Duquesne, built by the French at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. The Battle of Monongahela on July 9 was a disaster for the British. Under intense fire, George Washington carried the wounded Braddock from the field of battle. Washington “luckily escaped without a wound, though I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me.”5 Observing Washington’s bravery, Dr. Craik “expected at any moment to see Washington fall; his duty exposed him to every danger. Nothing but the care of Providence could have saved him from the fate of all around him.” Craik dressed Braddock’s wounds but three days later, the general died.6

After the debacle, the House of Burgesses authorized construction of a chain of forts to protect Virginia against attacks by the French and their Native American allies. Stationed at Winchester, Washington and his 2,000 Virginia militia defended a large section of the frontier. Washington appealed to the Virginia government to establish a military hospital at Winchester, directed by Dr. Craik. “The Surgeon has entreated me to mention his case,” wrote Washington, continuing,

He has behaved extremely well, and discharged his duty, in every capacity, since he came to the regiment. He has long discovered an inclination to quit the service, the encouragement being so small; and I believe would have done it, had not the officers, to show their regard for, and willingness to detain him, subscribed each one day’s pay, in every month; this, they intend to withdraw. [Dr. Craik] begs me to solicit the gentlemen of the finance committee in his behalf; otherwise, he shall be obliged to seek some other method of getting his livelihood. If it is thought necessary to establish a hospital, I believe there can scarcely be a doubt but that this is the place: and then I hope he will be appointed director, with advanced pay.

Washington’s letter had the desired effect. The Virginia treasury authorized payment to Dr. Craik of ten shillings a day and the lump sum of £50 for medicines. The finance committee instructed Washington “to hire a house for the sick and purchase necessities for them,” with Craik as medical director.7

In mid-1757 Washington became “acutely and dangerously” ill from dysentery, accompanied by fever and pleurisy. Dr. Craik sent him home to Mount Vernon to recover. “The disagreeable news of the increase of your disorder, is real concern to me,” wrote Craik to Washington, from Winchester on November 17;

I flattered myself with the pleasant hope of seeing you here again soon, thinking that the change of air, with the quiet situation of Mount Vernon would have been a speedy means of your recovery. However, as your disorder has been of long standing, and has corrupted the whole mass of blood, it will require some time to remove the cause. And, I hope by the assistance of God and the requisite care, that will be taken of you, where you now are, that though your disorder may reduce you to the lowest ebb, yet you will in a short time get the better of it; and render your friends here happy, by having the honor of serving once more under your command. As nothing is more conducive to a speedy recovery, than a tranquil, easy mind, accompanied with a good flow of spirits; I would beg of you; not, as a physician; but as a real friend who has your speedy recovery sincerely at heart; that you will keep up your spirits, and not allow your mind to be disturbed, with any part of public business . . . Any little step of this kind, that might happen, would be trifling to the neglect of yourself. The fate of your friends and country are in a manner dependent upon your recovery. I am sensible of the regard you have for both . . . but that you will use every endeavor that will be in the least conducive to your recovery so that both may still rejoice in the enjoyment of you.8

In 1758 the British and colonial governments in mounted a third campaign to drive the French out of the Ohio River Valley. Brigadier-general John Forbes commanded 2,000 British regulars and 4,000 colonial soldiers, of which 782 were with the First Virginia Regiment, led by Washington. With the large British force approaching, the French set fire to Fort Duquesne and abandoned the Ohio River Valley. In its place, the British constructed Fort Pitt, named for the British secretary of state, Pitt the Elder. The site became the city of Pittsburgh.

In 1758, Washington resigned command of the Virginia Regiment, disappointed that he did not receive a commission as officer in the British Army. In January 1759, he married the wealthy young widow Martha Dandridge Custis. From Winchester, Craik wrote to Washington:

We are very anxious here to know . . . who will be commander when the regiment meets with that irreparable loss, losing you. The very thoughts of this lies heavy on the whole whenever they think of it; and dread the consequences of your resigning. I would gladly be advised by you whether or not you think I had better continue . . . or whether I had better resign directly; for I am resolved not to stay in the service when you quit it. The inhabitants of this place press me much to settle here. I likewise would crave your advice whether or not you think I had better except of their importunities, or settle in Fairfax where you were so kind as to offer me your most friendly assistance. . .I have experienced so much of your friendship and received so much friendly countenance from you, I cannot help consulting you on this occasion as my most sincere friend.9

In his response, Washington offered to help Craik resign from the provincial army and set up a medical practice close to Mount Vernon. Craik was delighted by Washington’s offer. “Your most kind letter I had the great pleasure to receive, and acknowledge myself under new obligations for your repeated offers of friendship,” wrote Craik on December 29. “I wish it may ever be in my power to make you a suitable return for such friendship is seldom to be met with in those days.”10

Craik remained in Winchester with the regiment until early 1760, when he moved to Port Tobacco, Maryland, then a major port for the export of tobacco. He married Marianne Ewell, a distant relative of Washington. Craik established a thriving medical practice, specializing in inoculations against smallpox. He also set up a tobacco plantation, worked by slaves. In the fall of 1770, Washington traveled westwards with Craik and three servants to survey the bounty lands along the Great Kanawha River earned in return for their service during the French and Indian War. During the years 1760 to 1775 Craik and his family were frequent dinner guests, staying overnight at Mount Vernon. Craik provided medical care to the family and the slaves. Craik reported: “All your Negroes have been inoculated and all others in that neighborhood whom I have inoculated.”11

Service in War of Independence

With the thirteen American colonies at war with Great Britain, Gen. George Washington invited his friend, James Craik, to join the medical department of the Continental Army. Washington wrote from Morristown on April 26, 1777:

In the hospital department for the Middle District there are at present two places vacant, either of which I can obtain for you. The one is senior physician and surgeon of the hospital, with the pay of four dollars and six rations per day, and forage for one horse; the other is assistant director general, with the pay of three dollars and six rations per day; and two horses, and travelling expenses found.

You know the extent, and profit of your present practice; you know what prospects are before you. You know how far you may be benefitted, or injured by such an appointment; and you must know whether it is advisable or practicable, for you to quit your family and practice at this time. All these matters I am ignorant of; and request, as a friend, that my proposing this matter to you may have no influence upon your acceptance of it. I have no other end in view than to serve you; consequently, if you are not benefitted by the appointment, my end is not answered.12

On May 13 Craik replied to Washington:

I shall think myself honored by your procuring me the deputy director general place in the middle department, provided you think me capable of discharging the duties of that office. At the same time that I solicit for this appointment I must inform you, that in case my immediate attendance at camp is necessary, it will not be in my power to comply with it, as I have some families under inoculation near Fredericksburg whom I am not certain that I could leave under three or four weeks from this time.

To serve his friend and his country, Craik left his family and his profitable medical practice and take the position as “director of the hospitals near the grand army,” placing him in close contact with Washington.13 Craik supervised the care of ill and wounded soldiers as well treating, at Washington’s behest, a number of the senior officers of the Continental Army.

During the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, nineteen-year-old Marquis de Lafayette was shot in the leg. Craik dressed the wound and sent the young Frenchman to a hospital at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he rapidly recovered. During the Battle of Germantown, October 4, 1777, Gen. Francis Nash, commander of the North Carolina brigade, was wounded by a cannon ball to his thigh. “Covering the gaping wound with both his hands, Nash called out to his men: ‘Never mind me. I have had the devil of a tumble. Rush on, my boys, rush on the enemy; I’ll be after you shortly.’” Nash became faint from loss of blood. “He was attended by Dr. Craik, who gave his patient but feeble hopes of recovery, even with amputation.” The dying Nash told Dr. Craik: “It may be unmanly to complain, but my agony is too great for human nature to bear . . . I have fallen in the field of honor while leading my brave Carolinians to assault the enemy. I have one last request from his excellency, the commander-in-chief. That he may permit you, my dear doctor, to remain with me, to protect me while I am still alive, and my remains from insult . . . From the very first dawn of the Revolution, I have ever been on the side of liberty and my country.”14 General Francis Nash died in agony three days after the battle.15

After the British occupied Philadelphia, Washington led his army across the Schuylkill River to establish winter quarters at Valley Forge. The situation was desperate. Over three thousand of the eleven thousand soldiers of the Continental Army at Valley Forge were unfit for duty. The soldiers lacked clothing and shoes to face the icy weather. The spring of 1778 brought an increase of disease.16 Craik bore the responsibility to maintain medical services, recruit medical personnel and get desperately needed food, clothing, footwear, and medicines. On April 26, 1778, he appealed for supplies: “The army and hospitals are suffering for want of those things. The molasses here will not last longer than tomorrow, and there are at least one thousand soldiers under smallpox inoculation. Of wine, there has not been a drop in the hospitals for three weeks past . . . Ten or twelve hogsheads of molasses, at least, are needed . . . The hospitals are now full of sick, and I have neither utensils nor the necessities required to open new ones.”17

That spring, Craik busied himself with medical preparations for the evacuation from Valley Forge. On May 10, he wrote: “I am this day directed to have things in readiness to have all the sick of the army taken care of in case the army should make a sudden move, and to enable the Flying Camp to go along with the army.” Craik ordered several medical officers to remain behind to care for “the sick that will be left on the grounds, as there will not be less than fifteen or seventeen hundred.”18

French Troops Arrive

Determined to weaken the British, King Louis XVI of France provided money and troops to assist the Continental Army. From his headquarters at Morristown, New Jersey, on May 24, 1780, Washington sent Dr. Craik detailed instructions to travel to Providence, Rhode Island, to set up temporary hospitals for the use of the French army. Washington wrote:

The objects that demand your attention are these; to provide one or more convenient buildings for the reception of the sick belonging to the fleet and army . . . They must have apartments sufficient to contain these without crowding them, and so as to admit a separate distribution and treatment of each particular disease. They must have an airy and salubrious situation, be contiguous to each other, if possible, have yards and gardens, admitting easy communications from one to the other, so as to unite and facilitate the service.

Independent of the apartments for the sick, there must be one or more kitchens, an apothecary’s shop, a magazine for drugs and remedies, an oven, a bakery, a deposit for the provisions, lodgings for the director, surgeons, physicians and others employed with them; a magazine near for the effects of the hospital and, in short, all the conveniences that may promote this interesting service.

You will have provided such a number of oxen, sheep, poultry and vegetables as you deem necessary for the first demands of the hospital. I give you a letter for governor [William] Greene to furnish you with whatever aid you may want. You will make him an estimate and inform him to what extent his assistance will be requisite . . . You know how much we owe to our allies & what claims they have upon our gratitude and affection for a reciprocity of good offices.19

From Providence on June 11, Craik informed Washington of the difficulties he experienced in fulfilling his task.

On my arrival at this place, I laid your Excellency’s dispatches and my instructions before the governor, upon which a council was called when I was desired to attend. Previous to the meeting of the council I viewed the college [The College of Rhode Island, later Brown University], which stands on the back of the town, a little detached from it on a beautiful eminence. [It] is an elegant building . . . and well calculated both from situation and convenience for a complete hospital and would contain about six hundred sick. I was much pleased to find that only one small room was occupied by about fifteen scholars, and made no doubt of obtaining it on my first requisition. But when I attended the council, many excuses were made why I should not have it . . . Some said it would bring contagious diseases into the town. Others said it would stop the education of youth. Some said it had been greatly injured by the soldiery already and never had been repaired. And to conclude, the parson was sent for who said he must be entirely ruined if it was taken as he expected a greater number of scholars, from whom he hoped for considerable advantage. Upon the whole the reasons urged were sufficient to determine the council that I should not have it. And I was sent to look at a few barns about fifteen miles off and from thence fifteen miles farther to look at some old barracks; places by no means fit to put well people in, being the most dirty, vile huts, I ever saw. And if they were good [they] would not contain a hundred & fifty sick. Such were the places pointed out to me for hospitals. On my return from viewing these places I was fixed to the place where the barns are as being the most eligible & was to have them put in order to receive as many as they will contain. This place [Poppasquash] would do pretty well as the situation is tolerable provided buildings could be got ready in time but in all probability all the barns and buildings which they can erect in time upon that spot will not contain more than betwixt three and four hundred sick. Your Excellency can easily conceive the chagrin & uneasiness I feel at the small prospect I have at present of being able to comply with the spirit of my instructions. However, every effort in my power shall be used. Tomorrow the assembly meets . . . and I am told by some gentlemen that they will order me the college, if so, my prospect will be much better than at present. The people here [mostly] would do everything in their power to accommodate me, yet . . . some selfish view or other gets the better of their public spirit. Several convenient houses could be had in and about Newport. but I have imagined all along that you would think the sick too much exposed to the Enemy.

Should I be able to obtain the college, and that with the barns & barracks that are building should be insufficient to accommodate all the sick, I should be glad to know whether your Excellency would choose that any of them should be put into any of the houses about Newport, for I clearly see it will be impossible to have them altogether. If I am able to procure proper houses, I think everything else will be made agreeable.20

Despite considerable opposition, on June 17 the Rhode Island general assembly voted £10,000 to erect temporary hospital buildings in Poppasquash, Bristol, and Newport. Craik did not succeed in getting the College of Rhode Island.21 “After much fatigue and difficulty,” he wrote, “I have accomplished the business much to the satisfaction of the French and His Excellency George Washington.”22

Craik’s efforts to get buildings of the Rhode Island College for a hospital were frustrated by parson James Manning, a founder of the college, who took “great pains to inflame the people and make them believe that a disease not less mortal than the plague was to be brought in by the French fleet.” Craik also faced difficulties in procuring food supplies for the French soldiers. He felt “much mortified and chagrined at the disappointments I meet with in executing” Washington’s orders. These difficulties in negotiations with the Rhode Island council “have given me more uneasiness than anything I ever undertook.”23

Through Craik’s determined efforts seven barracks, a kitchen, pharmacy, laundry and bakery were erected at Poppasquash, large enough to care for 350 sick French soldiers. To Washington on July 6, de Corny wrote: “I am just arrived from Poppasquash; too much applause cannot be given to the zeal and attention of Doctor Craik . . . This hospital will be exceeding useful for summer, and for the convalescents.”24

On July 11, 1780 after a seventy-two-day journey across the Atlantic Ocean, the French fleet with thirty-two transports carrying 5,918 soldiers and sailors and 400 officers, entered Narraganset Bay in Rhode Island. The French troops were led by lieutenant general Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, conte de Rochambeau. On the long journey, many of the troops had fallen ill from scurvy, ague (malaria), cholera or smallpox.

General Washington was much pleased by Craik’s efforts. Such success warranted high promotion in the army medical department. On September 9, 1780, Washington wrote: “I think Doctors [John] Cochran and [James] Craik from their services, abilities and experience, and their close attention, have the strictest claim to their country’s notice, and to be among the first officers in the establishment . . . I have the highest opinion of them.”25 Dr. Craik “left a most extensive practice” to join the Army. He was “the greatest favorite” of general Washington.26 On January 3, 1781, Dr. William Shippen Jr. stepped down as director general of the army medical department, and was replaced by Dr. John Cochran, with Craik second in command and chief medical physician.27

Cochran and Craik asked Washington’s help to obtain a living salary for army physicians. “Many of the gentlemen of the hospital department have relinquished a practice, much more beneficial than any emoluments they can derive in the army and all of them would find their interest in returning to private life. We may have been willing to make sacrifices” only if medical staff salaries equaled those of army officers of similar rank, and, in addition, received “a handsome compensation in the future. Unless we are placed upon a footing more consistent with our feelings and the justice, we think due to use . . . it will be out of our power to continue in the service.”28

Yorktown, Virginia

The French army remained in Rhode Island until June 1781.29 Rochambeau led his troops from there to Philipsburg, New York on the Hudson River, to link up with the Continental Army. The combined French and Continental armies, numbering 15,000 men, under the leadership of General Washington, skirted British-held New York City and moved south through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware to reach Williamsburg, Virginia late September—a distance of 600-miles. Malaria, smallpox, fevers and battle wounds took their toll. The French converted buildings of the College of William and Mary into a temporary hospital for their troops. Dr. Craik, directing care for the Continental soldiers in flying hospitals, set up in Williamsburg and Hanover. On September 27, he informed general Washington: “The increase of our sick within these few days’ past, and a certainty of a still further increase as the season advances . . . makes me anxious to state to your Excellency our situation with respect to blankets. The hospital is entirely without this article. We have the greatest mortality to apprehend unless a proper supply can be instantly obtained.”30

The Siege of Yorktown began on September 28 and continued to October 19 with a decisive American-French victory. The joy on the battlefield was not matched by the concerns of the medical staff tending the sick and wounded. From a hospital near Yorktown on October 23, Craik wrote to Washington:

In the hospitals at Williamsburg there are about four hundred sick and wounded, at Hanover town about two hundred, and upwards of six hundred reported sick in the army . . . we have a number with smallpox and they are daily increasing . . . All the hospitals are destitute of blankets, shirts, overalls and clothing, all essentially necessary for the recovery of the sick. The department is entirely destitute of money, there is not a single copper to pay a nurse, or an orderly or to purchase milk and vegetables; and in a short time, stores and medicines will be wanting . . . The putrid diseases that now prevail in the hospitals and the wounded requires wine, as it is the best cordial that can be given them.31

John Parke Custis, son of Martha Washington, served as aide-de-camp to his illustrious stepfather. At Yorktown he was stricken with camp fever. Craik informed the family that there was no hope for the young man. Custis’s mother, his wife and General Washington were at the bedside when he died.

Service After the War

After the war Washington returned to private life at Mount Vernon. At Washington’s suggestion Craik moved to Alexandria, Virginia to be close to Washington and serve physician to him, his family and their 300 enslaved people. In 1793 Craik treated Anthony Whiting, Washington’s farm manager at Mount Vernon. In 1796, he treated Anna Maria, and Charles Augustin, Washington’s niece and nephew.

Following Washington’s two terms as president, Dr. Craik made twice-monthly trips to Mount Vernon to treat patients. Completing his medical work for the day, Craik frequently joined his friend George Washington for dinner, stayed overnight, took breakfast with him and then went on his way. Mrs. Marianne Craik, her sons William, George, James, and daughters Nancy and Marianne frequently joined Dr. Craik as dinner guests at Washington’s table. George and Martha Washington occasionally visited Dr. and Mrs. Craik at their home in Alexandria.

In 1797, Craik treated Christopher, Washington’s personal servant, who was bitten by a rabid dog. He also treated “two of your Negro women at Dogue Run” as well as “a visit to your people at the mansion house.” George Washington became ill on April 19, 1798 “with fever . . . and lasted until the 24th, which left me debilitated.” Craik diagnosed the illness as ague (malaria) and prescribed a stomach elixir, camphor, bark and the juice of oranges. On August 18, Washington was “seized with a fever which I endeavored to shake off by pursuing my usual rides & occupations, but it continued to increase upon me. On the 21st at night Doctor Craik was called in, and on the 24th procured a remission. Since which I have been in a convalescent state; but too much debilitated to be permitted to attend much to business.”32 “Mrs. Washington has been exceedingly unwell for more than eight days,” wrote George Washington on September 9, 1799. “Yesterday she was so ill as to keep her bed all day, and to occasion my sending for Doctor Craik the night before, at midnight. She is now better, but low, weak and fatigued, under his direction.”33 On November 27 Craik was at Mount Vernon to assist in the labor of Mrs. Eleanor Parke Curtis Lewis, granddaughter of Martha Washington and adopted daughter of George Washington. Eleanor gave birth to a daughter, named Frances Parke Lewis.34

Dr. Craik tabulated his medical services to Mount Vernon for the period between August 25, 1797 and June 14, 1799, listing forty-two visits and over 300 medical procedures, including medications. Craik adhered to the belief that illnesses were caused by “violent humors inside the body” that needed to be expelled by bleeding, blistering, purging, vomiting or sweating. Craik treated Washington, members of Washington’s family as well as the enslaved people. Whether arriving during the day or at night, Craik charged £1 per visit. Bleeding at 3 shillings each and blistering were Craik’s standard treatment method. In addition, he prescribed various cathartics, diaphoretics, laxatives, emetics, as well as opiates and bark. He set bone fractures and extracted decayed teeth. His charges were modest and “on many occasions he failed to charge a fee for a visit.” He was paid £97.11.9 in cash by farm manager James Anderson on June 27, 1799, a modest sum to settle the account for over one hundred and forty treatments over a twenty-two-month period.35

After the French revolution, privateers began seizing American ships and disrupting American trade with the Caribbean islands and Europe. By 1798 relations between France and the United States deteriorated and led to the Quasi-War. Fearing a French invasion, President John Adams called Washington out of retirement to be commander-in-chief of the Provisional Army, a position he held from July 13, 1798, until his death seventeen months later. For the position of director of the army medical department of the Provisional Army, Washington chose sixty-nine-year-old Dr. James Craik.

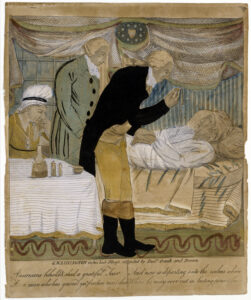

Washington’s Last Illness and Death

Despite severe weather on December 12, 1799, Washington mounted his horse and rode out to supervise the work on his farms. Returning home, he developed sore throat, could hardly speak and was breathing with difficulty, but the stoical Washington dissuaded his wife from calling for medical assistance until December 14. “Dr. James Craik hurried to George Washington’s side, not simply as his physician but as his oldest and most intimate friend.”36 Doctors Gustavus Richard Brown and Elisha Cullen Dick were called in to assist Dr. Craik. Dr. Brown diagnosed Washington with quinsy (diphtheria). Dr. Dick suggested a “violent inflammation of the throat.” Dr. Craik

put a blister of cantharides on the throat, took some more blood from him, and had a gargle of vinegar, & sage tea, and ordered some vinegar & hot water for him to inhale the steam, which he did; but in attempting to use the gargle he was almost suffocated. When the gargle came from his throat some phlegm followed it, and he attempted to cough, which the doctor encouraged him to do as much as possible; but he could only attempt it . . . Dr. Craik came again into the room & upon going to the bedside, the General said to him: ‘Doctor, I die hard; but I am not afraid to go, I believed from my first attack, that I should not survive it; my breath cannot last long.’ . . . He then said to Dr. Craik: ‘I feel myself going, I thank you for your attentions; but I pray you to take no more trouble about me, let me go off quietly; I cannot last long.’”37

Dr. Dick proposed a tracheotomy but Craik was not familiar with that procedure. On the evening of December 14, the sixty-seven-year-old George Washington died. Dr. Craik covered Washington’s eyes.

A week later, Drs. James Craik and Elisha Dick published an account of their futile efforts to save Washington’s life:

The necessity of blood-letting suggesting itself to the General, he procured a bleeder in the neighborhood, who took from his arm in the night twelve or fourteen ounces of blood. He could not by any means be prevailed on by the family to send for the attending physician till the following morning, who arrived at Mount Vernon at about 11 o’clock on Saturday. Discovering the case to be highly alarming, and foreseeing the fatal tendency of the disease, two consulting physicians were immediately sent for. . . in the meantime were employed two pretty copious bleedings, a blister was applied to the part affected, two moderate doses of calomel were administered, which operated on the lower intestines, but all without any perceptible advantage, the respiration becoming still more difficult and distressing. Upon the arrival of the first of the consulting physicians, it was agreed, as there were yet no signs of accumulation in the bronchial vessels of the lungs, to try the result of another bleeding, when about thirty-two ounces of blood were drawn, without the smallest apparent alleviation of the disease. Vapors of vinegar and water were frequently inhaled, ten grains of calomel were given, succeeded by repeated doses of emetic tartar, amounting in all to five or six grains, with no other effect than a copious discharge from the bowels. . . blisters were applied to the extremities, together with a cataplasm of bran and vinegar to the throat. Speaking, which was painful from the beginning, now became almost impracticable; respiration grew more and more contracted and imperfect, till half after 11 on Saturday night, retaining the full possession of his intellect; when he expired without a struggle. He was fully aware at the beginning of the complaint, as well as throughout every succeeding stage of it, that its conclusion would be mortal.” Washington approached his death “with equanimity.38

Modern-day speculations of Washington’s final illness suggest diphtheria, streptococcal throat infection, pneumonia, or acute bacterial epiglottitis.

1 George Washington’s Last Will and Testament, July 9, 1799.

2 The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 2, 2 January 1798 – 15 September 1798, ed. W. W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998), 382.

4 The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 1, 7 July 1748 – 14 August 1755, ed. W. W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 172–173.

5 Ibid., 336–338.

6 Life and Times of George Washington (Washington, DC: United States Bicentennial Commission, 1932), 1:239-240.

7 George Washington to John Robinson, August 5, 1756, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0293.

8 The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), 64–65.

9 The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 6, 4 September 1758 – 26 December 1760, ed. W. W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), 169–171.

10 Ibid., 172–173.

11 The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777 – 10 June 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 409–410.

12 Ibid., 272–273.

13 Ibid., 595–596.

14 George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (Washington, DC: Moore, 1859), 34-35.

15 Steven E Siry, Liberty’s Fallen Generals: Leadership and Sacrifice in the American War of Independence (Washington DC. Potomac Books, 2012), 79-80.

16 Mary Gillett, The Army Medical Department, 1775-1818 (Washington DC: U.S. Printing Office, 1981), 82.

17 James E. Gibson, Dr. Bodo Otto and the Medical Background of the American Revolution (Springfield, IL, and Baltimore: Charles C. Thomas, 1937), 162.

18 William S. Middleton, “Medicine at Valley Forge,” Annals of Medical History, Volume III, No.6 (November 1941).

19 Washington to James Craik, May 24, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0685. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 2, 1779–1781, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 330.

20 The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 26, 13 May–4 July 1780, ed. Benjamin L. Huggins and Adrina Garbooshian-Huggins (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018), 384–387.

21 Calendar of Correspondence of George Washington; Volume II, October 19,1778 to December 9, 1780 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1915).

22 “Letter of Dr. James Craik to Andrew Craigie,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series, Volume 36 (1901), 363.

23 The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 26, 493–495.

24 The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 27, 5 July–27 August 1780, ed. Benjamin L. Huggins (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 11–13.

25 Washington to James Duane, September 9, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-03221.

26 Morris Saffron, Surgeon to Washington; Dr. John Cochran (1730-1807) (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977), 219-221.

27 General Orders, October 19, 1780,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-03627.

28 Cochran to Washington, November 4, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-03812.

29 Norman Desmarais, “French Military Hospitals in Rhode Island,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 18, 2022, allthingsliberty.com/2022/04/french-military-hospitals-in-rhode-island/.

30 Craik to Washington, September 27, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07037.

31 Craik to Washington, October 23, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-0723.

32 The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 2, 580–583.

33 The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979), 363–367.

34 Ibid., 377.

35 Charles C. Wall, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Volume 55, No.4 (October 1947), 318-328.

36 Peter R. Henriques, He Died as He Lived: The Death of George Washington (Mount Vernon, Virginia: The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 2011), 29.

37 Tobias Lear’s Diary, December 14, 1799, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0406-0002.

38 James Craik and Elisha Dick, “Disease and Death of General Washington,” Medical Repository, Vol.3 (1800), 311.

8 Comments

Dear Mr Rosenberg,

I enjoyed your article on Dr. Craik, thank you.

Here is a related aticle I wrote, should you be interested.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2024/06/a-second-fight-for-freedom-the-enslaved-of-dr-james-craik-chief-physician/

To Michael Wood,

Thank you for reading my article on James Craik MD. I read your “Slavery and Indentured Servitude” with great interest. Hopefully, our research will heighten interest about Dr. Craik: Scottish immigrant, physician, slave owner, patriot, and above all, close friend to George Washington.

Good morning Mr. Rosenberg –

and thank you for this very nice article. Just FYI in case you don’t know that already: about a mile and a half east of Port Tobacco on 201 Port Tobacco Road in Charles County, Maryland, is “La Grange”, the home of Dr. James Craik (1730-1814). Craik purchase “La Grange” from William Smallwood and lived there between 1763 and 1783.

Well done article on a person in history that is mostly unknown but vitally important to understanding America’s founding. Thank you

My thanks to Robert Selig and Greg Wiesemann for their kind comments on my article on the little-known friendship between Dr. James Craik and George Washington. My thanks also, to the Journal of the American Revolution for providing us a platform to explore and describe events that took place around 250-years-ago and still shape our nation.

Mr. Rosenberg-

Having read several books on Washington I always felt myself longing for more substance and information on some of his intimate relationships. Dr Craik being his oldest and dearest friend was of utmost importance. Thank you for your article. The effort and energy you put into it leaps of the page.

Three of the doctor’s homes are still extant in Alexandria, Va.

Mr. Rosenberg, I read your article with interest, as I have been researching the background of Dr. Craik, specifically his medical education/training. Could you please tell me where you got the information that he graduated from the Unversity of Edinburgh Medical School. There are no records of him either attending or graduating from the school, according to university librarians/archivists. I look forward to discussing further with you this important historical personage.