As Founding Fathers of the United States met in Philadelphia to declare that “all men are created equal,” Thomas Craik Jr. was born into a family of people enslaved by Dr. James Craik on his Maryland plantations.[1] This was not unusual at the time; many of the colonial landed gentry relied upon slave labor to work their tobacco plantations, including George Washington himself. What makes this story unique is a series of records which allow us to document much of the family who were enslaved by Dr. Craik.

Slavery in Maryland

Slavery is a dark chapter in history; the retelling of an enslaved person’s story can never capture the pain and suffering of a life in bondage.

As lucrative as the colonial tobacco crop might have been, growing it was extremely labor-intensive. Maryland Governor Charles Calvert wrote in 1729, “Tobacco, as our staple, is our all, and indeed leaves no room for anything else. It requires the attendance of all our hands, and exacts their utmost labour, the whole year round.”[2] By the mid-eighteenth century, the plantation economy of Maryland relied almost exclusively upon slavery to supply the extensive numbers of field hands the crop required.

By 1755 enslaved Blacks accounted for 33 percent of Maryland’s total population; the concentration was even higher in the tidewater region.[3] In some tidewater counties, as much as half the population originated in Africa; many of the enslaved in Maryland originated in the Windward and Gold Coasts of West Africa, from Sierra Leone to Nigeria. Throughout the south, regular sales offering “fine, healthy Negroes” cx from the windward coast, were common.

At the outbreak of the Revolution, the demographics of Maryland’s enslaved population had changed significantly; some 90 percent of the colony’s enslaved people were native-born Americans. Political changes soon followed; in 1774 Maryland lawmakers officially ended the colony’s participation in the international slave trade. In Virginia, a 1778 law required those importing slaves from another state to give an oath confirming that the enslaved person was not imported from Africa and was not brought into Virginia for the purpose being sold.[4] Another, passed in 1792, stipulated that “slaves brought into this commonwealth, and kept therein for one year, shall be free, excepting those who may be inclined to remove from any of the United States, and become citizens of this State, if within sixty days after such removal, he or she shall take the following oath before some justice of the peace of the commonwealth”.[5] These laws, and their required oaths, would form the basis for several Freedom Suits brought by those who had been enslaved by Dr. Craik.

Dr. James Craik

The Craik family was of great prominence in the Chesapeake Bay region. Dr. James Craik of Charles County, Maryland, was one of George Washington’s oldest and closest friends, and the personal physician who attended to Washington on his deathbed. In his last will, Washington called him “my compatriot in arms and old and intimate friend”[6]

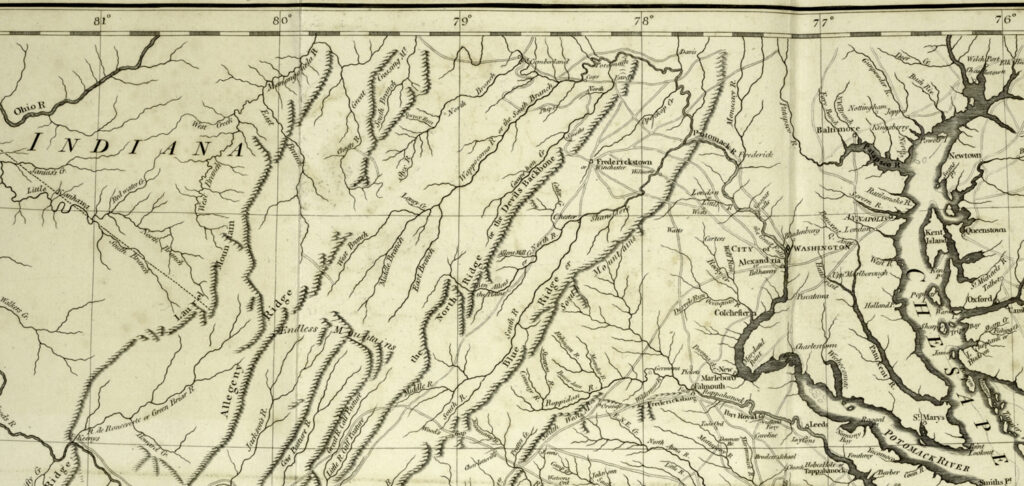

James Craik was born about 1730 in the Parish of Kirkbean, near Dumfries, Scotland. The son of William Craik, a member of the British Parliament, James studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh. In 1750 he immigrated to the West Indies to serve as a British army surgeon. He soon resigned his post and moved to Norfolk, Virginia where he opened a medical practice. Craik later maintained a farm at Vaucluse, near Winchester, and practiced as a surgeon based at Fort Loudon.[7]

In March 1754 he accepted a commission to serve as a surgeon in Col. Joshua Fry’s Virginia Provincial Regiment, alongside Lt. Col. George Washington, during the French and Indian War. Craik was with Washington at Fort Necessity in 1755 and with Braddock later that year.[8] Washington wrote of him in letter to Adam Stephen on November 18: “Doctr Craik is expected round to Alexandria in a Vessel with Medicines, and other Stores for the Regiment; so soon as he arrives I shall take care to dispatch him to you.”[9] Craik’s land holdings would grow significantly as a result of his service in the war.

On November 30, 1760 he married Mariamne Ewell, daughter of Charles Ewell and his wife Sarah Ball Conway, first cousin to George Washington. They wed at Belle Aire, in Prince William County. After the marriage, Craik moved across the Potomac to Port Tobacco, Maryland.[10] Together, the couple would have nine children

The Craik Plantation

Craik’s property in Maryland included the contiguous plantations of Prospect Hill, May Day, 234 acre Moore’s Ditch, which he purchased in 1763. Here he built his home, La Grange, around 1770.[11]

Craik was a major land holder. He is known to have held land in Hampshire County “on the North River” as early as 1771.[12] He held at least 7,000 acres in the Great Kanawha River tracts of Virginia, as did George Washington, in part granted to French and Indian War veterans.[13] He also owned land in Kentucky, and in Allegheny County, Maryland —which he noted were given to him “by that state for military services”—as well as homes and lots in both Washington and Alexandria.[14] The Great Kanawha River lands included those granted in December 1772 when the Virginia Council ordered that surveys be “immediately patented in the name of Dr. James Craik”; two parcels of 4,232 and 1,374 acres, noting that he “will fall short 394 acres of the 6,000 he has a right to, and be entitled at the next distribution to that quantity of land.”[15]

In recognition of his service in the Revolution, he would be eligible for 500 acres under the Acts of 1796 and 1799, and under the revised pension acts, his descendants were awarded 6,000 acres on March 12, 1832.[16]

The historical record shows that Dr. James Craik, as well as his sons Judge William Craik, James Craik Jr., Adam Craik and George Washington Craik, were all slaveholders. Although the exact number of enslaved persons working on the Craik plantations in Maryland is unknown, a 1782 tax assessment shows that Dr. Craik held twenty-two people in bondage.[17]

Although by 1798 the Craik estate had been sold to Francis Newman, and Dr. Craik was living in Virginia, it was in 1798 on the La Grange property that Josiah Henson was born, the enslaved man later depicted in Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The Revolution and the relationship with Washington

After the French and Indian War, Craik and Washington remained in close contact. Washington wrote of him with great praise:

The habits of intimacy and friendship, in which I have long-lived with Doctor Craig, and the opinion I have of his professional knowledge, would most certainly point him out as the man of my choice in all cases of sickness. I am convinced of his sincere attachment to me, and I should with cheerfulness trust my life in his hands.[18]

In the autumn of 1770, when Washington explored lands along the Ohio River, he set out from Mount Vernon on the 5th of October in company of Dr. James Craik.[19]

As early as 1774, Craik was active in the movement against British rule, and in 1777, at Washington’s bequest, he accepted a position in the Continental Army. In his letter to Craik of April 26. 1777, Washington offered him two positions:

Dear Doctor,

I am going to address you on a subject which may lay some claim to your attention, as I do to your candor in the determination of the proposition. In the Hospital department for the middle District (which District includes the States between the North or Hudson’s River, and Patowmack) there are at present two places vacant, either of which I can obtain for you: The one is Senior Physician, and Surgeon of the Hospital, with the pay of four Dollars and six Rations ⅌ Day, and Forage for one Horse: The other is Assistant Director General, with the pay of three Dollars and six Rations per Day; and two Horses, and travelling expenses found, according to Doctor Shippen’s (W.) Director General’s account, who also adds that he thinks this latter the most honourable and desirable of the two.[20]

Craik accepted Washington’s offer in May 1777, but as he was actively inoculating people against smallpox, he made it clear that he would not be immediately be able to report to camp:

At the Same time that I Solicite for this Appointment I must inform you that in case my immediat attendance at Camp is necessary, it will not be in my power to Comply with it as I have Some familys under Inoculation near Fredericksburgh whom I am not certain that I could leave under three or four Weeks from this time.[21]

Washington’s reply, until recently unpublished, read “I have referred the request contained in your letter to the Director General who knows how far it is in his power consistently with the good of the service to prolong your absence.”[22] Director General Dr. William Shippen Jr. did authorize Craik’s commission and delayed arrival at Valley Forge, but asked in return that Craik “assist & direct Dr Tilton one of our senior Surgeons who writes me he has near 1100 Carolinians, officers included, under inoculation at Dumfries, Alexandria & Georgetown.”[23] Craik’s work against smallpox was not without its dissenters, although he and Washington were of a like mind. While Craik was inoculating private citizens, Washington ordered that all soldiers that came through Philadelphia be inoculated.[24]

When Washinton’s leadership was questioned in the winter of 1777-1778, it was Craik who warned him of the “Conway Cabal,” a group of men wishing to replace Washington with Horatio Gates. In January 1778, Craik wrote to his friend warning that

you are not wanting in Secret enemies who would Rob you of the great and truely deserved esteem your Country has for you … If they are your Enemies every honest man must naturally conclude they are Enemies to the Country and the Glorious Cause in which we are engaged, and will no Doubt most Streneously exert every Nerve to dissapoint their Villainous intentions.[25]

In 1781 Craik was promoted to Chief Physician and Surgeon of the Army, a commission that he held until the end of the war. He was instrumental in setting up the hospitals that provided medical support to the French troops in Rhode Island during their stay in 1780 and 1781.

Although exaggerated, Craik’s grandson James Craik D.D. (1806-1882), recalled that the doctor was with Wasington in “every battle that he fought from Great Meadows to Yorktown.”[26] Craik was certainly at Yorktown in October 1781, reporting to Washington on the casualties of the battle: “In the Hospitals at Williamsburg there are about four hundred sick and wounded, at Hanover Town about two hundred, and upwards of six hundred reported sick in the army—those in Hanover Town.”[27]

After the war, at Washington’s suggestion, Craik settled in Alexandria, Virginia, and became Washington’s personal physician.[28] He was admitted as an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland in November 1783.[29]

Craik was clearly a popular traveling partner. When in September 1784, George Washington again set out to visit his lands “west of the Apalacheon Mountains,” he “set out myself in company with Docter James Craik.”[30]

Craik continued to serve as Washington’s personal physician during his lifetime. Letters between the men, as well as Craik’s medical ledgers, indicate that he was a regular visitor at Mount Vernon. He was there as often as twice a week, providing services to Washington’s household and his enslaved population, including inoculating them against smallpox.[31]

In the midst of the Quasi-War with France, a limited naval war against French privateers who were seizing U.S. shipping, in November 1798 Washington called the country’s most senior officers together and tasked them with identifying senior officers who should be recommended to President Adams for commissioning.[32] On the recommendation of Washington, Dr. James Craik was selected as Physician-General of the Army.[33]

Craik was present at Washington’s death bed on December 14, 1799. Washington told him, “Doctor, I die hard; but I am not afraid to go; I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it; my breath can not last long.” Afterward, the other doctors were dismissed and only Craik remained in the room. Washington spoke, requesting to be “decently buried” and to “not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead.”[34] Craik publically recounted Washington’s passing with the words,

I, who was bred among scenes of human calamity—who had so often witnessed death in its direct and most awful forms, believed that its terrors were too familiar to my eye to shake my fortitude—but when I saw this great man die, it seemed as if the pillar of my country’s happiness had fallen to the ground.[35]

The death of Washington while in Craik’s care did not seem to impact his renown as a doctor. Many physicians in colonial North America were trained through apprenticeships, and every two years, in 1799, 1801 and 1803, Dr. Craik advertised for “A Young Man of Good Character” to apprentice with him in the “study of medicine.”[36]

Craik’s documented record of caring for the health and well-being of others would appear to stand in stark contrast to his position on human slavery; to his credit, he did actively care for the health of his enslaved population and made an effort to keep enslaved family groups together. Perhaps he, like his friend George Washington wrote in 1799, was “principled against this kind of traffic in the human species” and felt that “To hire them out, is almost as bad, because they could not be disposed of in families to any advantage, and to disperse families I have an aversion.”[37]

Post war slavery

The“importation” of enslaved people from Maryland to Virginia was already subject to a duty of 20 percent, but the Act of 1785 further stipulated that enslaved persons “born in another state and brought into Virginia” after the date of the act would be freed after spending one year in the state. As such, clandestine importations were rampant.[38]

As they were considered taxable property, records of the names of those held in bondage on any given plantation can be inaccurate; even more difficult is establishing family groups and ancestry amongst enslaved peoples. Additionally, the practice of loaning or selling slaves between plantations complicates the historical record. Tracing the family history of persons enslaved in the eighteenth century is especially difficult, made more so by the general practice of using only given names to identify enslaved people.

The number of persons held in bondage by the Craik family increased in the years between 1782 and 1790. In the 1790 census, the Craik family reported holding twenty-four enslaved people in Maryland—in addition to those imported by Dr. Craik to Virginia—counting them among the larger slaveholders in the area.[39]

Bought, sold & hunted

Slave labor was a valuable commodity in Maryland; thus aside from being considered part of an inheritance, these persons and their labor were rented, traded and sold as active commodities.

The average value of an adult male slave in the southern colonies in the early 1780s was $1,110. Because a runaway slave represented a loss of capital, slaveholders actively pursued runaways, both through local sheriffs and with vigilante justice. Those who ran away from the Craik estate included “Josh the property of Craik’s estate well known in town as a fiddler and much marked with the small pox”; a five dollar reward was offered for delivering him to the town goal.[40] In June 1798, James Craik placed an announcement in the local newspaper advising that two people had “Absconded” from his plantation, “a negro man named Joe, and a mulatto girl named Ann.” He warned anyone “harboring or employing them,” that he “shall in such case persecute the offender as the law directs.”[41]

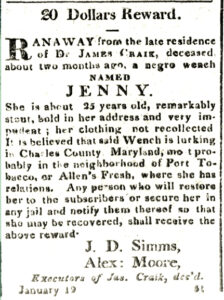

After his death, the estate of James Craik placed an advertisement offering “20 dollars reward” for the return of “a negro wench name Jenny . . . about 25 years old . . . runaway from the late residence of Dr. James Craik.” For those wishing to pursue the bounty, her possible whereabouts were given: “it is believed that said wench is lurking in Charles County, most probably in the neighborhood of Port Tobacco, or Allen’s Fresh, where she has relations.”[42]

Despite his relocation to Virginia, James Craik initially retained his properties and slaves in Maryland; these were not transferred to his son William until 1796.[43] William Craik, who had been elected to Congress that year, sold all his Charles County lands and many of his slaves, the sales finalized by 1798.[44] William predeceased his father in 1807. At the settlement of William’s estate, it was noted that “all my negroes not herein otherwise disposed of” shall be left to “my much beloved and respected father and mother for and during their natural lives,” stipulating that after their deaths that four specific “negroes” and their “future increase” should go to his father and mother, then after their deaths to his nephew James Craik, “son of my brother George Washington Craik” (1774-1808). The four enslaved people named in this document were “Archibald and his wife Betsy and her feature increase,” “Rose and her future Increase” and “Lewis.”[45]

The slaves of Willam Craik “otherwise disposed of” appear to have been transferred to John Winter Sr. (1712-1781, m. Elizabeth Bruce). Winter was a tobacco farmer who owned multiple plantations in Charles County; The Meadows, Meadows Marsh, The Old Gray Plantation, Orphin Loss, Grays Fancy, Westwood Manor, St. Thomas’ Manor and Nanjemoy. When John Winter Sr. wrote his will in 1780, he named his “one Negroe man named Tom Craik, his wife Jude, her daughter Chloe, Victory, Beck, Hezekiah, Tom, Matilda, all children of Tom Craik & his wife Jude” to be left to his son John Winter, Jr., as well as a silver can, four silver spoons, and other “property.”[46]

John Winter Jr. (1761-1799, m. Elizabeth Mason) died in 1799; the administrator Richard Mason presented an inventory of the “goods and chattels” belonging to the estate. Rather than simply listing the total number of enslaved people, as was commonplace, Winter provided the names and ages of the enslaved. These included:

Thomas Craik Sen. aged 64, Adam aged 35, Gerard a carpenter aged 35, Thomas Craik Jr. aged 23, Samuel aged 12 [listed twice], Notly aged 12, Gerard aged 10, John aged 10, Thomas aged 7, Levy aged 3, and the women Mary aged 65, Chloe aged 36, Rebecca Sen. aged 30, Ann aged 20, Juda Sen. aged 16, Rebecca Jr. “on the east shore” aged 14, and Juda Jr. aged 5.[47]

The “value” recorded for Thomas Craik Jr. was eighty-five pounds. The names of at least seven of the twenty-two slaves John Winter Jr. claimed in an earlier tax assessment, including Tom’s wife Jude Craik and her children Victory, Beck and Hezekiah, do not appear on the 1799 list. As Jude does not appear in any later records, she might have died before 1799. Her daughters Beck and Victory do appear in later records, as does one slave named Hezekiah, of the right age to be Tom Craik’s son. A Hezekiah, born about 1779, appears on the 1795 inventory of the estate of Thomas Winter of Charles County, the son of John Winter’s first cousin.

The people enslaved held by John Winter Jr., including the Craik family, would pass in large part to his son John Winter II, who died before 1801, the enslaved persons passing to his sister, Eliza Winter (b. abt. 1788), listed as “nearest of kin” in the inventory of his estate that was recorded on October 15, 1801. The document lists twenty-three enslaved people:

Tom Crack Sen. aged 70 years, Adam aged 45 years, Tom Crack Jun. aged 30 years, Gerard carpenter aged 45 years, Sam aged 14 years, Notley aged 13 years, Gerard aged 11 years, John aged 9 years, Thomas aged 6 years, Levi aged 5 years, John aged 2 years, Hezekiah aged 1, and the women Chloe aged 40 years, Beck aged 30 years, Vick aged 36 years (author’s note: poss. Tom’s daughter, Victory), Anney aged 25 years, Jude Crack aged 21 years, Beck aged 15 years, Jude aged 7 years, Peggy aged 4 years, Priss aged 1 years, Jenny aged 20 years and Moll aged 60 years.[48]

As was the case in the inventory list taken in 1799, Jude Craik and her son Hezekiah were not recorded, perhaps sold to another plantation, deceased, or simply overlooked. Victory and Beck Craik—who were not included in the 1799 inventory—were recorded in 1801, clearly showing that these inventory lists were not always definitive. The ages of enslaved persons were often estimated, as can be seen by the variations between the two lists. Of importance, this inventory uses the spelling “Crack”, which Tom Craik used in later years.

The Freedom suits

At the close of the eighteenth century, several former slaves of Dr. James Craik sued for their freedom.

The Virginia slave importation laws required that anyone bringing an enslaved person into the state must “take an oath within 60 days after his removal” confirming that the person was not imported from Africa and was not brought into Virginia for the purpose of being sold. This law, and its legal interpretation by the courts, formed the basis for many slaves to sue their enslavers for their freedom.

Before his relocation to Virginia, Dr. James Craik held twenty-two slaves on a plantation of 495 acres.[49] Exactly when and how many were later brought with him to Virginia is unclear, as well as whether Craik took the correct oath required by the State of Virginia. Those who sued testified that Craig imported them into Virginia around the year 1792. It is these importations that would later cause Craik to be subpoenaed to appear in court.

Enslaved people were often backed by Quakers or other opponents of slavery, when they sought freedom through the judicial process. Dr. Craik faced freedom lawsuits brought by Joseph Harris, Betsy Scarlett, Ann Williams, Mathilda Thompson and Ann Caruthers, but the outcome of these cases is unknown.[50]

In 1799, the enslaved Rose, noted in the estate settlement of William Craik, sued for her freedom. In the case of “Negro Rose, Harry, & Joe v. James Kennedy Jr.,” Rose claimed that James Craik brought her into Virginia in 1792, and she claimed to be free because her owner had not taken the oath prescribed by the Act of Virginia of December 17, 1792.

The case took nearly three years, with James Craik summoned to testify twice, in July 1801 and in April 1802. The jury initially found for the plaintiff Rose, but on appeal the defendant (James Kennedy Jr.) produced a certificate by T. Hooe, a justice of the peace, of an “oath taken by the owner on the 28th of December, 1792.” The jury then ruled for the defendant. Rose and her children remained enslaved.[51]

Death of Dr. James Craik

Dr. James Craik and his wife, Mariamne Craik, died within months of each other, he in February 1814 and she in April 1815. The well publicized story of his attentiveness at Washington’s death bed contrasts vividly with his own passing, which came quietly in in Alexandria. Even his own obituary was but one line – the rest of the notice being about his attendance to Washington in 1799.[52] His resting place in the cemetery of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House remained unmarked until 1928, when descendants placed a slab in his honor.[53]

In his last will, dated June 5, 1813, Dr. Craik left “my said wife Mariamne her heirs and assigns forever the following slaves to wit Parker, Janney, Myrtilda and her children, Mary, Paris [possibly Tom Craik’s daughter Priss], Lucy, William and Matilda, and all the future increase of the said Janney Myrtilda, Mary, Lucy and Matilda.”[54]

Apparently Dr. Craik had remained active and in good health in his old age, continuing to practice medicine until just a few years before he died. He himself reflected on his later years, saying, “Age was as a lusty winter—frosty but kindly.”[55]

His wife moved to Alexandria after her husband’s passing, but followed him in death not long afterwards. Her will dated April 10, 1815 mentioned only “my woman, Myrtilla and her children,” specifying that “if they are sold they must be sold for a term of years—they must not be sold for life out of the family.”[56]

The Supreme Court

In an 1805 case, Loudon v. Scott, the court ruled that a slave brought into Virginia in 1802, by a person removing from Maryland, and omitting to take the oath within sixty days after his removal, was entitled to freedom. This precedent case triggered others to sue, including “Myrtilda, Mary, Lucy and Matilda,” who James Craik had left to his wife Mariamne in 1814 and she in turn left to her daughters.

Matilda filed a Petition for Freedom in 1822. She argued, as had Rose in 1799, that James Craik had violated the law of 1792 which forbade slaves to be brought to Virginia for the purpose of selling them. A separate case was filed for her minor son William, who was held in bondage by others.[57] Matilda claimed, “on the grounds of negress Matilda, their mother, having been removed in the year 1792 from Charles County in the state of Maryland to Fairfax County in the State of Virginia, by a certain Doctor Craik,” that she and her children were free.[58]

She lost the case in October, but was immediately granted a new trial. On June 13, 1823, she won her freedom—but it would be short lived. The defendant appealed in August and the issue went to the Supreme Court of the United States, whose judgment in January 1827 reversed the lower court:

One James Craik, through whom the plaintiffs in this court make title, some time in the year 1792, brought Matilda from the state of Maryland into Fairfax county, in Virginia, and there settled and resided until his death, in all about two and twenty years. During this time, the three children of Matilda were born, and the whole continued to be held by him in slavery, during his life, and at his death, were bequeathed to his wife, who bequeathed them to the wives of Moer and Mason. The whole time which elapsed from the bringing of Matilda into Virginia to the commencement of this suit, was thirty years.

Matilda and her children remained in bondage. There was, however, one exception.

Tom Craik’s Manumission

By the time of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Maryland’s laws regarding slavery, as revised in 1796, remained in force, making it difficult for slaveholders to free their slaves. The rules for granting manumission required that the enslaved person be “of healthy constitution and sound in mind and body, capable by labor to procure them sufficient food and raiment with other requisite necessities of life.” The law was additionally restrictive by allowing only enslaved people under the age of forty-five to be offered their freedom. Previously, persons up to the age of fifty could be manumitted.[59]

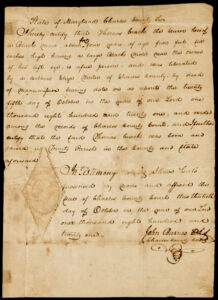

Thomas Craik Jr. was forty-four years old in 1821, living in bondage under Elizabeth Winter in Alexandria. Whether motivated by his approaching age limit, influenced by the increasing abolitionist movement, or through a personal change of conscience, Eliza Winter gave Thomas Crack Jr. his freedom on October 25, 1821.[60]

State of Maryland Charles County

I hereby certify that Thomas Crack the bearer hereof a black man about forty four years of age five feet six inches high having a large black mole near the corner of his left eye, is a free person, and was liberated by a certain Eliza Winter of Charles County, by deed manumission bearing date on or about the twenty fifth date of October in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty one, and enroled among the record of Charles County Court, and I further certify that the said Thomas Crack was born and raised in Trinity Parish in the county and state aforesaid.

In testimony whereof I have hereto subscribed my name and affixed the seal of Charles Count Court this thirtieth day of October in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty one.

John Barnes Clerk Charles County Court

In the census of 1830, Thomas Crack Jr. is recorded as a Free Colored Person, living alone in Allens Fresh, Charles County, Maryland. The hamlet of Allens Fresh borders directly on Trinity Parish, where Thomas was born. He had finally returned home, a free man.[61]

Epilogue

Members of the enslaved family of Tom Craik lived in bondage for a full century; with certainty from the birth of Tom Craik Sr.’s first son in about 1776 until the Virginia Constitutional Convention resolved to abolish slavery on March 10, 1864.

The existence of this rare sequence of documents allows the story of the enslaved Craik family to be partially reconstructed. These documents may be unique to this family, but the story they represent is exemplary of many others who lived in bondage during this period.

Whether Thomas’s father, Tom Craik Sr., lived long enough to see his son achieve freedom, no record exists. Elizabeth Winter is not recorded holding any persons in bondage after 1821. As for the rest of Tom’s family, we can only speculate.

[1] Inventory of the estate of John Winter, probated April 30, 1799, Charles County Inventories 1798-1802, June Term 1799, (Annapolis MD, Hall of Records), 140-141.

[2] Benedict Calvert, Calvert Papers, Number two (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1894), 70.

[3] Maryland State Archives, “A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland”, p.4, msa.maryland.gov/msa/intromsa/pdf/slavery_pamphlet.pdf.

[4] Virginia General Assembly, A Collection of All Such Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia of a Public and Permanent Nature, as are Now in Force (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, Jun., and Henry Pace, 1814), Act of the December 17, 1792, p. 262.

[5] Matilda Derrick, Lucy Derrick, Louisa Derrick, & Matilda Derrick v. George Mason & Alexander Moore, Supreme Court of the United States, January Term 1827, summary at “O Say Can You See”, William G. Thomas and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.report.0013.002.

[6] George Washington’s Last Will and Testament, July 9, 1799, www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-source-collections/primary-source-collections/article/george-washingtons-last-will-and-testament-july-9-1799/.

[7] James Craik, www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/james-craik/.

[8] James Craik, twitter.com/FtNecessityNPS/status/1093255374201913344.

[9] George Washington to Adam Stephen, November 18, 1755, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-02-02-0178.

[10] Gay Moore, Seaport in Virginia, George Washington’s Alexandria (Alexandria: Garrett and Massie, 1949), 184-194.

[11] Willie Graham (principal investigator), Maryland Historical Trust, “The Architecture of Domestic Support Structures in Southern Maryland”, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2020, pp. 46-47, mht.maryland.gov/Documents/research/contexts/FRRMary40.pdf.

[12] Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), October 17, 1771.

[13] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, October 15, 1805.

[14] Fairfax County Courthouse, Fairfax County Virginia Will Book, James Crsaik, Vol K1, 1812-1816, pp. 180-183.

[15] Virginia Gazette (Rind), January 14, 1773.

[16] M. G. Brumbaugh, Revolutionary War Records, Volume 1, Virginia (Lancaster: Lancaster Press, 1936), 97.

[17] Maryland State Papers, Scharf Collection Online, 1782 Tax Assessment, James Craik, MDSA s1005_107_15-0004.

[18] Letter to James McHenry, 3 July 1789, in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The writings of George Washington (Washington: USGPO, 1939), 30:351.

[19] John W. Wayland, “Washington West of the Blue Ridge,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 48, No. 3 (July 1940), 193-201.

[20] Washington to James Craik, April 26, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-025.

[21] Craik to Washington, May 13, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0404.

[22] The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, letter in a private collection, “May 31st, 1777, “General George Washington Manages the First Major Inoculation Campaign in American History and the Continental Army Medical Department”, www.raabcollection.com/presidential-autographs/washington-medical-als.

[23] William Shippen, Jr. to Washington, June 2, 1777,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0593.

[24] National Park Service, Smallpox, Inoculation, and the Revolutionary War, Boston National Historical Park, www.nps.gov/articles/000/smallpox-inoculation-revolutionary-war.htm. See also ), Letter to James McHenry, July 3,1789, The writings of George Washington, 7:102-106.

[25] Craik to Washington, January 6, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0126.

[26] “Boyhood Memories of Dr. James Craik, D.D., L.L.D. Rector of Christ Church, Louisville, Ky., 38 Years,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 46, No. 2 (April 1938), 135-145.

[27] Craik to Washington, October 23, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07237.

[28] National Museum of the United States Army, Biographies, James Craik, www.thenmusa.org/biographies/james-craik/.

[29] James Schmidt, The Maryland Line and the Creation of the Society of the Cincinnati, Maryland State Archives, 2019, msamaryland400.com/2019/10/25/the-maryland-line-and-the-creation-of-the-society-of-the-cincinnati/. See also: Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Maryland Archives Online, 48:483-484, msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000048/html/am48–483.html.

[30] George Washington Diaries, 4:14, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-04-02-0001-0001.

[31] James Craik, Invoice for services provided, November 14, 1791, Box: 24, Folder: 1791.11.14, RM-873; MS-5334, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Washington Library, archives.mountvernon.org/repositories/3/archival_objects/4946. See also Amy Speckart, “New Perspectives on Haberdeventure Plantation in Charles County, Maryland, 1770–1787.” The Organization of American Historians and The National Park Service (February 2022), 41, www.nps.gov/thst/learn/historyculture/upload/508_THST-Final-508-3.pdf. See also J. M. Toner, “A Sketch of the Life of Dr. Gustavus Richard Brown,” Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia Quarterly Magazine 2, no. 1 (January 1923), 18-19.

[32] Robert Gough, “Officering the American Army, 1798,” The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 43, No. 3 (July 1986), 460-471.

[33] Aurora General Advertiser, Philadelphia, July 20, 1798.

[34] Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Washington Library, Center for Digital History, Digital Encyclopedia, “Death of George Washington,” www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/the-death-of-george-washington/.

[35] The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 18, 1814.

[36] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, June 24, 1803.

[37] Robert Lewis to Washington, August 17, 1799, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0211.

[38] Donald M. Sweig, “The Importation of African Slaves to the Potomac River, 1732-1772,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 4 (October 1985), 518-519.

[39] 1790 United States Federal Census, Maryland, Charles County, William Craik, p. 10. 1790 Virginia census records were lost.

[40] Hall’s Wilmington Gazette, August 24, 1797.

[41] The Columbian Mirror And Alexandria Gazette, June 12, 1798.

[42] Alexandria Gazette, Commercial and Political, February 9, 1815.

[43] Charles County Deed Books, Liber IB 2/47.

[44] Webster et al., In Search of Josiah Henson’s Birthplace (St. Mary’s City MD: St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2017), 24.

[45] Chancery Court Records, 1807 William Craik of Alexandria, (Richmond VA, Library of Virginia), Index No. 1827-023.

[46] Will of John Winter, probated February 6, 1781, Register of Wills Charles County, AF 7.590, 590-593.

[47] Inventory of the estate of John Winter, probated April 30, 1799, Charles County Inventories 1798-1802, June Term 1799, (Annapolis MD, Hall of Records), 140-141.

[48] Inventory of the estate of John Winter, October 15, 1801, Charles County Maryland Inventory Accounts, June Term 1802, (Annapolis MD, Hall of Records), 491-492.

[49] Amy Speckart, “New Perspectives on Haberdeventure Plantation in Charles County, Maryland, 1770–1787,” The Organization of American Historians and The National Park Service (February 2022), 27, 125, www.nps.gov/thst/learn/historyculture/upload/508_THST-Final-508-3.pdf.

[50] Gloria Whittico, “The Rule of Law and the Genesis of Freedom: A Survey of Selected Virginia County Court Freedom Suits (1723-1800),” Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review, 9.2 (2018), 463.

[51] Negro Rose, Harry, & Joe v. James Kennedy Jr., United States. Circuit Court (District of Columbia) – Alexandria (Washington, D.C.), summary at “O Say Can You See”, earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0383.

[52] The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 18, 1814.

[53] Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 9, 1928.

[54] Fairfax County Courthouse, Fairfax County Virginia Will Book, James Craik, Vol K1, 1812-1816, pp. 180-183.

[55] Alexandria Gazette Commercial and Political, February 10, 1814.

[56] Alexandria City Courthouse, Alexandria City Virginia Will Book, 1815-1821, Mariamne Craik, Vol 2, 1810-1831, p. 56.

[57] William Derrick v. David Read & Silas Read, summary at “O Say Can You See”, earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0422.

[58] Matilda Derrick, Lucy Derrick, Louisa Derrick, & Matilda Derrick v. George Mason & Alexander Moore, Supreme Court of the United States, January Term 1827, summary at “O Say Can You See”, earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.report.0013.002.

[59] Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1796, Chapter LXVII, Volume 105, p. 255, Archives of Maryland Online, msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000105/html/am105–255.html.

[60] John Barnes (Clerk of the Charles County Court), Manumission papers of Thomas Crack, original document dated 1821, privately held, digital copy in the personal collection of Michael M. Wood.

[61] Bureau of the Census, 1830 U.S. Federal Census, Allens Fresh, Charles, Maryland, Series M19, Roll 56, (Washington DC, NARA, 1830), 138.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...