Thomas Waters of Georgia was present in crucial events of the American Revolution in Georgia and South Carolina. He represented as an individual the problems of class and conscience affected by British efforts to restore the rebelling Southern colonies by “Americanizing” the war, what has been called the Southern Strategy. After 1778, the King’s ministers risked Britain’s empire in a global war with France and later Spain in hopes that respected local Loyalist leaders like Waters would rally African Americans, European emigrants, indigenous peoples, and native-born white Americans to restore to the Crown the colonies from Maryland southward, and perhaps eventually more.[1]

Waters’ background, like most of his life, remains an enigma to scholars. In the 1783 Spanish census of East Florida, he was recorded as born in England.[2] A descendant believes he was born around 1735, the son of Richard and Mary (died 1747) Morgan Waters of England and Wales.[3] James Wright found Thomas Waters in the Second Troop of colonial rangers when Wright arrived in Georgia in the 1760s to assume the governorship. Thomas and Richard Waters served as cadets in the Second Troop starting on April 1, 1761. By July 1, Thomas had received a promotion to Quartermaster.[4]

The rangers maintained civil order, patrolled for escaped enslaved people, and scouted for marauding whites and indigenous people. Most of that troop had been recruited from the population on the colony’s northwest frontier, near Augusta. Because of having these two provincial troops of soldiers to enforce the law, Georgia was the only one of the twelve colonies that would later rebel that issued the King’s stamped paper during the Stamp Act Crisis of 1766. Because of public sentiment against these tax stamps, the governor had not dared to call out the militia for fear of arming more men against him than for the King. Paying for this colonial equivalent of the modern Georgia Highway Patrol had always been a problem, however. General Thomas Gage finally ordered the two Georgia ranger troops disbanded in 1767.[5]

Thomas Waters likely came to Georgia as a young apprentice businessman. He resided in South Carolina and in Augusta, Georgia. In the latter, he became involved with merchants in trade with the indigenous people. He acquired various parcels of land in Georgia and South Carolina. In 1765, he became a commissioner for building a public fort and barracks in Augusta, and won election to the colonial Georgia House of Assembly from frontier St. Paul Parish, today’s Columbia and Richmond counties. The following year, Waters became a justice of the peace. In 1767, he joined his neighbors in warning the governor of the potential for trouble when settlers on the Little River, near Augusta, burned the village of indigenous people who allegedly stole horses.[6]

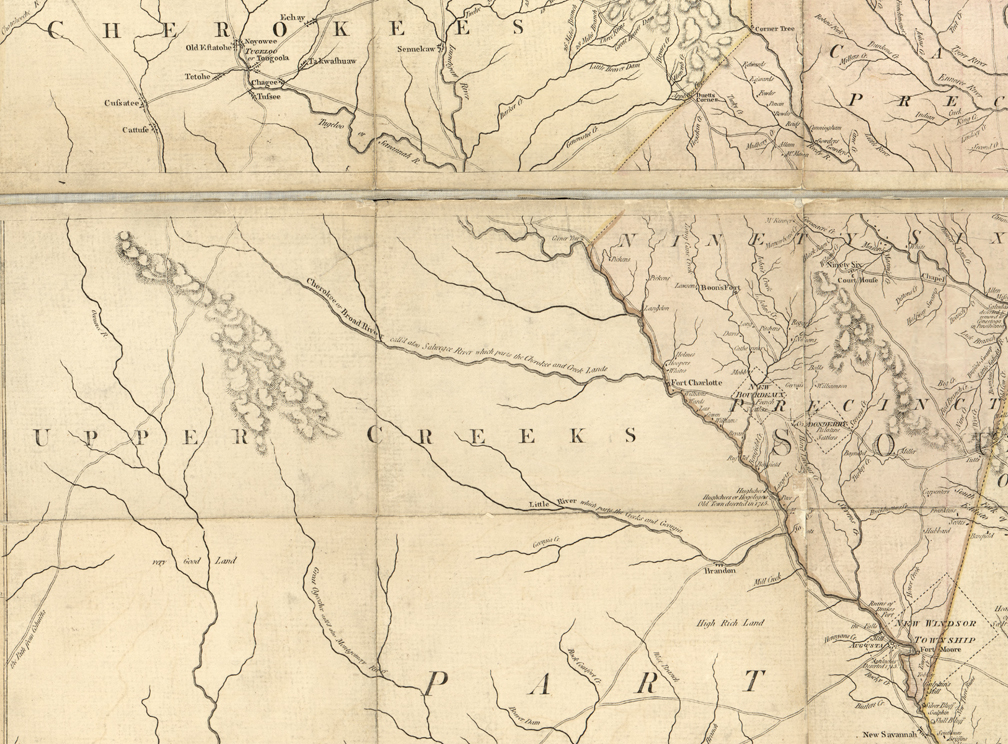

Governor James Wright led a project in 1773 that would exasperate the problems with the indigenous peoples. Through his efforts, Georgia acquired some 1.6 million acres of territory from the Cherokee and Creek tribes to the northwest of Augusta that became known as the Ceded Lands, what is today’s Wilkes and surrounding counties. Money raised from the land sales was intended to pay the debts owed by the Cherokees and Creeks to the merchants of Augusta and their British backers, as well as for a troop of rangers to patrol the new acquisition.

Wright attempted social engineering. He intended to restrict the size of the land grants to encourage small farmers, with few if any enslaved people, from outside of Georgia. They had to be able to raise money for the land, but they received property tax exemptions. On the edge of the Ceded Lands, William Manson and Thomas Brown also established settlements of indentured servants and opened stores, as an economic depression fueled migration from Great Britain in the early 1770s and as the Colonial Board of Trade tried to end the headright system of free land grants in America.[7]

Middle-class settlers for the Ceded Lands could form a free white militia to contend with threats to the province by bandits, bands of indigenous peoples, and insurrections by enslaved persons. Wright publically proclaimed that the rangers would enforce the colony’s vagrancy laws against the landless whites, “Crackers and Virginians” as he styled them, whom he saw as a class of bandits responsible for troubles with the indigenous peoples.[8]

Thomas Waters became a major player from the beginning in the history of this new acquisition. He and his now business partner Edward Barnard helped to survey the lands. Waters served as a first lieutenant in the new ranger troop under Capt. Edward Barnard, and, after Barnard’s death on June 6, 1775, under Capt. James Edward Powell, both formerly officers of the old Second Troop of the 1760s Rangers.[9]

As an officer in the new troop of horse rangers, Waters also received a commission to enforce the law as justice of the peace. These men operated out of Fort James at the fork of the Savannah and Broad Rivers in the northeast and a stockade on the north fork of the Ogeechee River near Wrightsborough, in the southwest, supplied from corn fields planted around the forts. Each ranger wore a blue coat faced in red, with a red waist coat, blue cloth boots (trimmed in red with black straps and buckles), and blue or buckskin pants. The rangers served at the formal treaty negotiations at Augusta between Governor Wright and the Cherokee and Muscogean (Creek) leaders, accompanied the survey of the area, and served with the St. Paul Parish militia in 1774 when hostile Muscogee war parties, upset by the loss of these lands, attacked settlements along the Little River. The militia and rangers suffered defeat but the now Sir James Wright, the governor, ended the crisis through negotiations that resulted in the assassinations of the leaders of the war parties. Settlement of the Ceded Lands nonetheless failed financially.[10]

Thomas Waters, however, had ambitions beyond serving as a ranger. Around the mouth of the Broad River and along the Savannah River, as well as near Wrightsborough, on the edges of the Ceded Lands, he established plantations of 4,500 acres where his forty-four enslaved persons and twelve skilled laborers raised cattle, hogs, horses, Indian corn, indigo, oats, peas, sheep, and wheat. His holdings included a blacksmith shop, a fort, a large two-story house, and three mills. Additionally, he loaned money to many of the 200 families who settled in the Ceded Lands with which they could make their initial land payments.[11] Among the borrowers was Elijah Clark, a completely illiterate landless frontiersman from Craven County, South Carolina, who claimed a modest tract of 150 acres.[12]

The American Revolution began as the Ceded lands opened. Waters and his people across the Georgia frontier signed public protests opposing the rebellion in 1774. Some signatories like Elijah Clark, John Dooly, and Barnard Heard, however, would later join the Revolution.[13] The resistance grew and, that same year, Continental Captains Pannill and Walton arrived at Fort James to demand that the rangers surrender that post. Captain Powell and Lieutenant Waters refused but their men defected and would serve as a company in the Georgia Continentals until later ambushed and killed by an indigenous war party on the southern frontier.[14]

Waters would not join the rebels, although he was given every encouragement. The previously mentioned Englishman Thomas Brown, an outspoken Loyalist who was exiled to British East Florida after nearly being tortured to death by a mob in Augusta, could not learn Waters’ politics in 1776. In 1777, the Georgia Executive Council tried to commission Waters as a justice of the peace, but local Patriot leaders insisted, for reasons unknown, to commission someone else. In 1778, the new state of Georgia required that supporters of the King promise not to work against the Revolution. Waters took that oath. At that time, John Coleman, commander of the new state Patriot militia regiment in what the state constitution of 1777 designated as Wilkes County, still considered Waters as his trusty friend.[15]

By February 1779 a British army had captured Savannah, overran the state as far north as Augusta, and took oaths to the King from 1,400 Georgians of the state’s small population. Only the Ceded lands/Wilkes County remained unconquered, although a delegation from there arrived offering to surrender their forts to the British and take an oath of allegiance to the King. Even in Augusta, eighty Loyalist Provincial horsemen from the British army under Scottish Captains Dugald Campbell and John Hamilton made a circuit to obtain the submission of all Wilkes County’s men and forts.[16] They visited Waters’ plantation. Waters joined the King’s cause and became one of Georgia’s most important Loyalists (Tories). On August 28, 1779, a Wilkes County grand jury denounced that he and others had aided the invading British army. In May 1780, Charlestown, South Carolina, the South’s largest city, surrendered along with the American army that defended it. British regulars and Loyalists then swept across Georgia and most of South Carolina. What remained of Georgia’s state militia surrendered and became prisoners of war on parole.[17]

Small bands of Patriot partisans under Elijah Clark and others remained in the field but the situation had become pacified enough that British leaders could now implement its overall strategy to restore the southern colonies to the Crown. Sir James Wright had returned as colonial governor, and with the re-establishment of the assembly, Georgia became the only American state reduced to colony status. Thomas Waters became colonel of the Fifth Colonial Militia Regiment (Ceded Lands) and justice of the peace. Stephen Heard, the state governor in exile, regarded Waters as one of the Patriots’ greatest enemies. Wright would remember Waters as a man of property and character.[18]

Wright and many other loyal American leaders feared that the Revolution in Georgia and South Carolina only smoldered and that it could rekindle. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in North America, made matters worse on June 3, 1780, by ordering almost all male citizens in Georgia and South Carolina to serve in the colonial militias, essentially canceling their paroles. The restored colonial Georgia assembly banned from public office men who had supported the Revolution.[19]

Under these circumstances, Loyalists believed that the war had begun again when, in September 1780, Elijah Clark led 400 partisans in almost capturing the Loyalist garrison and native warriors in Augusta, under now Lt. Col. Thomas Brown. Rescued and reinforced by South Carolina Loyalist provincials from Ninety Six, South Carolina, the King’s men took revenge on the families of Wilkes County, the source of most of Clark’s following. Lieutenant Colonel John Harris Cruger, the leader of the relief column, dispatched Colonel Waters’ militia regiment, with accompanying indigenous warriors, to destroy the forts, the courthouse, and the settlements of the Patriot families in Wilkes County. They and their allies destroyed at least 100 homes. Sixty men who had supported Clark became prisoners in Augusta. Cruger had other prisoners put to death, some by the indigenous peoples.[20]

Elijah Clark gathered 700 refugees, men, women, and children, Black and white, and they fled along South Carolina’s western border with the Cherokees to try to reach safety in modern Eastern Tennessee, where the war had not yet reached. They traveled for eleven days in harsh winter weather and often without food. British Maj. Patrick Ferguson set out with his corps of Loyalist American provincials and impressed South Carolina colonial militia to intercept the fleeing Wilkes County refugees. At King’s Mountain, South Carolina, Ferguson was killed, and his command destroyed, by state militia from as far away as Georgia, today’s Tennessee, and Virginia, with men from the Carolinas, on October 7, 1780.[21]

Back in Georgia, Brown, Cruger, and Waters had created rather than suppressed a widespread uprising. Reportedly, Clark’s band had largely come from an apolitical class of frontier brigands fighting civil authority long before the war, but other members only came along under threats to their lives and property. Now, men and other Georgians who had retired from the war were driven back into it and on the side of the rebellion. Royal Lt. Gov. John Graham took a census of Wilkes County and came away anything but encouraged. He found that of 723 men, now only 255 could be counted on for Waters’ King’s militia and that at least 411 men had joined the rebels.[22]

Even that number of colonial militiamen would severely decline. Cruger, who now took command of both the Georgia and South Carolina frontier, ordered this Ceded Lands Georgia Loyalist militia to his Ninety Six District of South Carolina to meet out punishment to suspected supporters of the Revolution in the Fair Forest Creek area. Waters may have also intended to establish a fort and powder magazine there. At Hammond’s Store, near South Carolina’s Bush River, on December 28, 1780, Col. William Washington, with seventy-five continental horsemen and 200 refugee militiamen under Lt. Col. James McCall of South Carolina and Maj. John Cunningham of Wilkes County, Georgia, attacked Colo. Thomas Waters and his 250 member Georgia Loyalist militia regiment. The two sides lined up across from each other, but the Loyalists fled without firing a gun in the face of a cavalry charge by Washington and his men. Waters reportedly lost 150 men killed and wounded, 40 men taken prisoner, and 50 horses captured.[23]

Wilkes County neighbors had fought on opposite sides at the Hammond’s Store in South Carolina. Likely, some of the men who died as Loyalists there at Hammond’s Store had been Georgia Patriot Wilkes County militia almost two years earlier when they had defeated South Carolina American Loyalists from Raeburn Creek (near Hammond’s Store) at the battle of Kettle Creek in Wilkes County. Many of those Loyalists were emigrants or the sons of emigrants defeated by native-born Americans.[24] Ironically, as with some of Clark’s men in Augusta, many of the South Carolina Loyalists at Kettle Creek had only come because of threats from their neighbors.[25]

The situation turned even worse for the King’s men. Clark, Cunningham, McCall, and many other Whig partisans returned to Georgia to regain the state from British control. Men from today’s East Tennessee came to Wilkes County to help Elijah Clark’s Patriot militia while, conversely, thirty of these same “Overmountain” men reached Augusta to serve with Brown’s Loyalist garrison.[26] Captains Cane and Tillett of what remained of Waters’ regiment won some local victories, but saving the area for the King became a lost cause. By February 1781, Waters reported that eleven of his neighbors had been assassinated.[27] The local killings became so infamous that in the South, the murder of prisoners came to be cynically called “granting a Georgia parole.”[28]

In April 1781, Waters provided slaves to help build Fort Cornwallis, a massive fortification at Augusta to protect the Loyalists from future attacks. He and his militia were among the Loyalists who surrendered there on June 1, 1781, to Lt. Col. Henry Lee, Brig. Gen. (of militia) Andrew Pickens, and Lt. Col. Elijah Clark. With Col. Thomas Brown and the other prisoners, Waters traveled under guard to be released in British-held Savannah, but not before his Maj. Henry Williams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt by one of Clark’s men.[29]

Thomas Waters took on new duties shortly afterward. General Sir Henry Clinton appointed him deputy superintendent to the Cherokees in January 1782, and Waters moved to the Indian village of Long Swamp, near present-day Ball Ground, Georgia, where he organized the warriors for the King’s cause. At one point, he led 1,000 Cherokees. In September 1782 Pickens, with 400 men, and Clark, with 100 men, invaded the Cherokee nation in search of Waters. They destroyed Long Swamp village in what scholars have called the last battle of the American Revolution in America but Waters and his followers escaped.[30]

The British completely evacuated Georgia and South Carolina by December 14, 1782. Waters and his Cherokees escaped to St. Augustine, but East Florida was returned to Spain in exchange for the return of the Bahamas to Britain, to conclude this still unnamed world war. In the Spanish census, a financially stressed Waters was recorded as a grocer and as having a wife, two children, and an orphan girl in his household. He had taken as his wife Sally Hughes, the Cherokee relation of merchant and interpreter John Vann, Waters’ former business associate.[31]

The civil war that had broken out across America during the Revolution resulted in tens of thousands of people, not all of them Loyalists, leaving the new nation with the war’s end to parts of Africa, the Americas, Europe, and even as far as the Pacific Islands.[32] Waters was among these refugees. With his six-year-old son George Morgan Waters, he sold his last eleven enslaved people and other portable property and moved to New Providence in the Bahamas and then to England in 1786. From East Florida in 1783, Waters had filed a claim with the British government for his losses of £9,111, of which he eventually received £4,824 and a £60 per annum pension. Educated in England, George M. Waters returned to Georgia in the 1790s and settled in the former Loyalist community in Bryan County with his sister Mary, who had married Alexander McQueen Netherclift.[33] George became a planter of prominence and wealth in both the Cherokee Nation and the state of Georgia, his fortune was built partly on what Thomas Waters left him.[34]

The restored state of Georgia attained Thomas Waters of treason and confiscated his property, giving his extensive Savannah River plantation to his enemy Col. Elijah Clark as a gift (Clark already occupied the property). Waters’ banishment was removed on February 1, 1788. In 1800, from England, he attempted to collect debts owed to him from before the Revolution.[35] He likely died in London in 1813.[36]

As with many other men of his colonial middle class, Thomas Waters sought his fortunes on the frontier of a developed and developing America, where he succeeded and failed within Britain’s policies, world war, and its aftermath. He was heavily involved with British efforts to begin a counter-revolution of Americans restating and even fighting the American Revolution in Georgia and the South, from the battle of Kettle Creek in 1779 to the last battle of the war in America in 1782. Yet the epic tale of of this Loyalist remains, as it has always been, in the shadows.

[1] George Germain to Sir Henry Clinton, March 8, 1778, in K. G. Davies, ed., Documents of The American Revolution, 1770-1783, 19 vols. (Dublin, IRE: Valentine Mitchell, 1973-1983), 15:58-59. For the execution of Southern Strategy see Richard Sears Dukes, Jr., “Anatomy of a Failure: British Military Policy in the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution, 1775-1781” (Ph. D. diss., University of South Carolina, 1993); John S. Pancake, This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas 1780-1782 (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1985); and David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina, and Georgia, 1775-1780 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005); and on ethnicity of the Loyalists, see Brad A. Jones, Resisting Independence: Popular Loyalism in the Revolutionary British Atlantic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021) and Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South 1775-1782 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2008).

[2] Lawrence H. Feldman, The Last Days of British Saint Augustine 1784-1785:

A Spanish Census of the English Colony of East Florida (Baltimore: Clearfield,

1998), 31-32.

[3] Morgan-Waters Family Bible, Collection of Family Bibles, 1639-1905, GHS 1609, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah; Don L. Shadburn, Unhallowed Intrusion: A History of Cherokee Families in Forsyth County, Georgia (Forsyth, GA: the author, 1993), 11-12; family tree chart submitted by Christy Munday, Denver, CO, Ancestry.com, www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/160069633/person/232278274865/facts. Other Waters family researchers believe that Thomas Waters was from South Carolina, the son of Philemon Waters, and that he lived for some time after the American Revolution in South Carolina. “A Discussion of the Hudson Book on Colonel Thomas Waters c 1738 – aft. 1810”: jeanday1.tripod.com/Waters_Discussion_of_the_Hudson_book.htm and Thomas Carleton Hudson, George Morgan Waters Family History (privately printed, 1973), 5; also see the Thomas Waters file in St. Augustine (Florida) Historical Society.

[4] Deposition of Sir James Wright, December 4, 1783, Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office Papers, 13/38/118; Murtie June Clark. Comp., Colonial Soldiers of the South, 1732-1774 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1983), 1048, 1050.

[5] James Michael Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Recoats: The Military in Georgia (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1992), 67-68, 91-96; Robert S. Davis, “Georgia’s Colonial Rangers,” Historical Society of the Georgia National Guard Journal 8 (3) (Spring/Summer, 2001): 11-14.

[6] An Index to Deeds of the Province and State of South Carolina 1719-1785 and Charleston District 1785-1800 (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1977), 356, 820; Alan D. Candler and Lucian Lamar Knight, comps., The Colonial Records of the State of Georgia 26 vols. (Atlanta: various publishers, 1904-1916), 9:607, 10: 248, 272, 14: 481, 641; Shadburn, Unhallowed Intrusion, 14.

[7] Bondurant Warren and Jack Moreland Jones, comps., Georgia Governor and Council Journals, 9 vols. (Athens, GA, 1991-2008), 4:142-143, 5:10-11; Farris W. Cadle, Georgia Land Surveying History and Law (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 36-37, 39. For the settlements by Brown, Gordon, and Manson see Robert S. Davis, Quaker Records in Georgia: Wrightsborough, 1772-1793, Friendsborough, 1775-1777 (Augusta: Augusta Genealogical Society, 1986). The Ceded Lands began as a scheme by George Galphin to obtain land from the Cherokees that tribe had lost in a war with the Muscogee (Creek) tribe. The land would be sold to pay the debts owed by the Cherokees to merchants such as Galphin. Alex M. Hitz, “The Earliest Settlements in Wilkes County,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 40 (September 1956): 260-280; Clay Ouzts, Samuel Elbert and the Age of Revolution in Georgia, 1740-1788 (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2022), 110; William P. Brandon, “The Galphin Claim,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 15 (Winter, 1931): 113-141; Joshua Piker, “Colonists and Creeks: Rethinking the Pre-Revolutionary Southern Backcountry,” Journal of Southern History 70 (August 2004): 503-540.

[8] Memorandum of Wright to the Earl of Hillsborough, December 12, 1771, in Kenneth Coleman and Milton Ready, eds., Colonial Records of the State of Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979), vol. 28, pt. ii: 356-358; Edward J. Cashin, Lachlan McGillivray, Indian Trader (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), 271-75. For the Ceded Lands see Robert S. Davis, “William Bartram, Wrightsborough, and the Prospects for the Georgia Backcountry, 1765-1774” in Kathryn E. Holland Braund and Charlotte M. Potter, eds. Fields of Vision: Essays on the Travels of William Bartram (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010), 15-32, and for Sir James Wright see the upcoming Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2024).

[9] “Instructions to Edwd. Barnard Esq. Captain of the Troop of Rangers to be raised to keep good order amongst and for the protection of the inhabitants in the ceded lands above Little River” and Thomas Waters’ commission as lieutenant, September 6, 1773, Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office Papers 13/38/113-117; Clark, Colonial Soldiers of the South, 998-1005.

[10] Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Recoats, 97-101.

[11] Memorial of Colonel Thomas Waters, n. d., Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office 13/38/106-114 and 124-143, Treasury Papers 79/39/362; Sharon P. Flanagan, “The Georgia Cherokees Who Remained: Race, Status, and Property in the Chattahoochee Community,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 73 (Fall, 1989): 589; Robert S. Davis, comp., The Wilkes County Papers, 1733-1833 (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979), 36, 44-46, and Supplement to the Wilkes County Papers (1773-1889) (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 2000), 92-94.

[12] Grace G. Davidson, comp., Early Records of Georgia Wilkes County 2 vols. (Macon, GA: Burke, 1932), 1:8; Elijah Clark to Dr. McDonald, December 9, 1794, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina Papers, 1V11, Lyman C. Draper Collection, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison.

[13] Robert S. Davis, comp., comp., Georgia Citizens, and Soldiers of the American Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979) 16, 19.

[14] Deposition of Shadrach Nolen, March 17, 1834, Revolutionary War pension claim of Shadrach Nolen, GA/SC S-4622, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900 (National Archives microfilm M804, roll 1824), Records of the Veterans Administration Record Group 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington; Lachlan McIntosh to George Walton, Lyman Hall, and Nathan Brownson, December 17, 1776, in “The Papers of Lachlan McIntosh,” ed. Lilla M. Hawes, Georgia Historical Society Collections (Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, 1957), 12:24.

[15] Thomas Taylor to Thomas Percy, January 13, 1776, Miscellaneous Collection, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, MI; Edward J. Cashin, The King’s Ranger: Thomas Brown and The American Revolution on The Southern Frontier (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1989), 27-29; Davidson, Early Records of Georgia Wilkes County, 1:34; Margaret Godley, comp., “Minutes of the Executive Council, May 7 Through October 14, 1777,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 33 (June 1949): 327-328; Allen D. Candler, comp., The Revolutionary Records of the State of Georgia, 3 vols. (Atlanta: Franklin Turner, 1908), 2:26-27.

[16] Robert S. Davis, “A Frontier for Pioneer Revolutionaries: John Dooly and the Beginnings of Popular Democracy in Original Wilkes County,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 90 (Fall 2006): 351-353.

[17] Memorial of Colonel Thomas Waters, n. d., and “Schedule to which the annexed Memorial refers,” Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office 13/38/109-111, 114; Davis, “A Frontier for Pioneer Revolutionaries,” 342-343; Mary B. Warren, comp., Georgia Governor and Council Journals, 1778-1779 Savannah Under Siege (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 2007), 11; Davidson, Early Records of Georgia, 2: 10.

[18] Stephen Heard to Richard Howley, March 2, 1781, Keith Read Collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection, University of Georgia Libraries, Athens, GA; Gordon Burns Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 2 vols. (Milledgeville, GA: Boyd Publishing, 2006, 2011), 1:165; deposition of Sir James Wright, December 4, 1783, and militia service November 12, 1780-January 31, 1781, Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office Papers, 13/38/115, 118, 129.

[19] Davis, “A Frontier for Pioneer Revolutionaries,” 343, and Georgia Citizens and Soldiers of the American Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979), 67-70; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:213-215.

[20] William Stevenson to Susannah Kennedy, September 25, 1780, in The Remembrancer, Or Impartial Repository of Public Events, vol. 11, part 1 (1781): 281; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:213.

[21] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:213-214, 219-221.

[22] Return of the Fifth Georgia Militia Regiment, November 12, 1780-January 31, 1781, Audit Office Papers 13/4/311, National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew, UK; Heard Robertson, “The Second British Occupation of Augusta,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 58 (Winter 1974): 422-446.

[23] Daniel Morgan to Nathanael Greene, December 31, 1780, in in Richard K. Showman, ed., The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 13 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC, 1976-2015), 7:30-31; Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South 1775-1782 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2008). 239-240; Andrew Waters, “Hammond’s Store: The ‘Dirty War’s’ Prelude to Cowpens,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 10, 2018, allthingsliberty.com/2018/12/hammonds-store-the-dirty-wars-prelude-to-cowpens/; Thomas Young, “Memoirs of Major Thomas Young,” South Carolina Magazine of Ancestral Research 4 (Summer 1976): 184; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:226-227. For biographies of the Patriot commanders at Hammond’s Store, see Bobby Gilmer Moss, The Patriots at the Cowpens Revised Edition (Blacksburg, SC: Scotia Press, 1985). Major John Cunningham of Clark’s Wilkes County militia had been a Continental officer and would play a major role in the Patriot victory at the Battle of Cowpens. Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:91, 179, 226, 231-234, 236 n. 27, 264, 2: 88-90, 379.

[24] Robert S. Davis, “Loyalism, and Patriotism at Askance: Community, Conspiracy, and Conflict on the Southern Frontier,” in Robert M. Calhoon, Timothy M. Barnes, and Robert S. Davis, Tory Insurgents: The Loyalist Perception and Other Essays (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010), 250.

[25] Deposition of Joseph Cartwright, September 1, 1779, North Carolina Papers, 1 KK 108, Lyman C. Draper Collection.

[26] Piecuch, Three Peoples One King, 254; Tarleton Brown, Memoirs of Tarleton Brown (New York: privately printed, 1862), 11-12.

[27] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:254-255; Mary B. Warren, comp., Chronicles of Wilkes County, Georgia (Athens: Heritage Papers, 1978), 22.

[28] Dr. Thomas Taylor to Rev. John Wesley, February 28, 1782, Shelbourne Papers, William L. Clements Library; “SAVANNAH, MARCH 14,” Royal Georgia Gazette (Savannah), March 14, 1782; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, So Far as It Related to the States of North and South Carolina and Georgia, 2 vols. (New York: D. Longworth, 1802), 2:336; E. W. Carruthers, Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character Chiefly of the Old North State (Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell, 1854), 431; Harold E. Davis, The Fledgling Province: Social and Cultural Life in Colonial Georgia, 1733-1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 17.

[29] Robertson, “Second British Occupation,” 436, 439-441; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:245-248; Clyde R. Ferguson, “General Andrew Pickens,” (Ph. D. diss., Duke University, 1960), 208-227; Cashin, The King’s Ranger, 129-138; deposition of James Wright, December 4, 1783, deposition of Thomas Brown, 1783, Loyalist Claim of Thomas Waters, Audit Office Papers,13/38/114-115, 118-120.

[30] Ferguson, “General Andrew Pickens,” 271-277; Robert S. Davis, “The Cherokee Village at Long Swamp.” Northwest Georgia Historical and Genealogical Society Quarterly 14 (1) (January 1982): 34-38; Andrew Pickens to Henry Lee, August 28, 1811, Thomas Sumter Papers, 1VV107, Lyman C. Draper Collection; Mary Bondurant Warren, comp., Revolutionary Memoirs and Muster Rolls (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 1994), 146; Clark to John Martin, November 3, 1782, Joseph Valance Bevan Papers, Mss 71, Box 1, folder 9, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah.

[31] Feldman, The Last Days of British Saint Augustine, 31-32; Shadburn, Unhallowed Intrusion, 20-22; Hudson, George Morgan Waters, 5; Shirley Joiner Thompson, The People of Camden County, Georgia: A Finding Index Prior to 1850 (Jacksonville, FL: The author, 1982), 127.

[32] See Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Penguin, 2011) and Carole Watterson Troxler, “The Migration of Carolina and Georgia Loyalists to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick,” (Ph. D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1974).

[33] Flanagan, “The Georgia Cherokees Who Remained,” 590; Peter W. Coldham, comp., American Migrations 1765-1799 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2000), 790; Gregory Palmer. Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution (Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing, 1984), 515; no title, Columbian Museum and Savannah (Georgia) Advertiser, June 28, 1806.

[34] See Sharon P. Flanigan, “George Morgan Waters: A Social Biography.” Master’s thesis, University of Georgia, 1987) and Thomas J. Waters, et al, v. Richard Arnold, Savannah Circuit Court, National Archives at Atlanta, Morrow.

[35] Warren, Revolutionary Memoirs, 164, 168-169; no title, Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle and Gazette of the State, February 21, 1801.

[36] A Thomas Waters of Gulston Street, White Chapel, age eighty-two, was buried at St. Mary’s White Chapel. Middlesex Parish Registers, 1539-1988, London Metropolitan Archives, London, UK, available on Familysearch.org, May 5, 2024, www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/3734475.

One thought on “Fighting in the Shadowlands: Loyalist Colonel Thomas Waters and the Southern Strategy”

Very interesting article on Thomas Waters! Thank you…