In January 1792 forty-three-year-old Arthur Bowler left Halifax, Nova Scotia, on his second Transatlantic journey. Captured in Africa almost thirty years earlier, enslaved in Newport, Rhode Island, for nearly twenty years, a free man for ten, he was returning to Africa.

He left fragmentary clues buried in archives on three continents which illuminate an “ordinary” person caught up in extraordinary circumstances. While he was not a major historical figure, leaving no personal papers or images, fighting in no wars, these clues allow insight into slavery in urban New England before and during the American Revolution. They also illustrate the dislocations and opportunities resulting from American independence, as well as the complex and intertwined worlds of abolition and empire.[1]

Bowler’s experience contributes to the growing scholarship on Loyalists and also complicates the treatment of the “back to Africa” movement, often seen as a negative step for formerly enslaved people.[2]

First clue: Cesar Lyndon’s Account and Memorandum Book 1765.

Our first glimpse of Arthur is when his name appears in an account book. On July 8, 1765 Cesar Lyndon wrote: “To cash to Arter Bowler for ye ordr [. . .] or 18/ & 2 Coppers 1—0—6.”[3] Arthur was selling something to the enslaved and literate Cesar Lyndon in Newport, Rhode Island.

The enslaved Cesar Lyndon was secretary and amanuensis to Josias Lyndon (1704-1778) who as Clerk to the Rhode Island General Assembly was a colleague of Arthur’s enslaver Metcalf Bowler (1720-87). Merchant, privateer owner, politician and superior court judge, Bowler was speaker of the General Assembly.

Cesar Lyndon ran a number of businesses, renting plots of land to fellow slaves, leasing out piglets to be raised for a share of the profits when they were slaughtered, trading with merchants in Surinam, and buying silk dresses for his wife and silver knee buckles for himself. He was very far along a continuum from servitude to freedom, and it is likely Arthur Bowler’s degree of enslavement in Newport was less physical compared with say, a field laborer in the South or enslaved workers in nearby Narragansett, Rhode Island.[4]

What Cesar was purchasing from Arthur is a mystery, but nevertheless this fragment of evidence provides several clues. Specie was scarce in the colonies, and Rhode Islanders had to manage the exchange rates between different currencies. Arthur, who we discover from a later clue was born in Africa, cannot have been in Newport long. Most slave voyages were suspended during the Seven Years War (privateering was more profitable) but he was clearly well known to Cesar Lyndon. He had a new name, he could speak enough English to communicate, and he could understand variable currencies. He also had sufficient latitude from his enslaver to be doing some trading on the side.

Second clue: A Letter, 1774.

A letter dated “Portsmouth Jany 14th 1774” was addressed in a flowing script, “To Mr Willm Vernon, Mercht in Newport p Arthur.” Metcalf Bowler, the writer, had recently sold his large Newport house and moved to nearby Portsmouth. The purchaser was William Vernon (1719-1806), one of Newport’s most prolific slave traders, with over forty such voyages. He was, however, slow to pay and Bowler needed his money, so in January 1774 he sent his “Servant” Arthur with a letter, explaining that as he was going to Boston the next day, he could not wait on Vernon in person “but have sent my servant with this, requesting you would without fail, deliver him, the two hundred Dollars you promised to have in readiness for me . . . I have inclosed a receipt for that sum.”[5] This suggests that Arthur was a well-trusted and well-known “servant.”

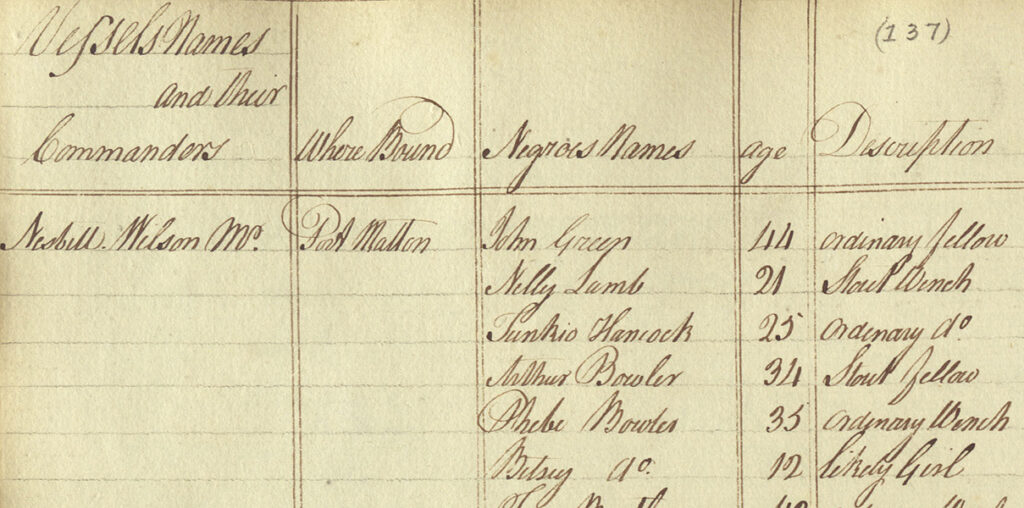

Third clue: The Book of Negroes, 1783.

Nine years later Arthur Bowler, now with a wife and daughter, appears in the Book of Negroes, a British list kept in case Americans wanted to claim compensation for their human property.[6] The British freed many enslaved people as part of the war effort, and now the war was over, they were evacuating three thousand Blacks and 27,000 white Loyalists from New York City, Arthur, Phebe and Betsy Bowler among them.

Accordingly, on November 19, 1783 they lined up to board a British transport ship, the Nisbet. They were among the last Blacks to leave New York, their names appearing towards the end of the second volume of the ledger. They had already acquired certificates saying they were free to travel, stating that the bearer had His Excellency Sir Guy Carlton’s permission “to go to Nova Scotia, or wherever else [he or she] may think proper.”[7]

A clerk transcribed Bowler’s name phonetically as “Boler” and his former owner as “Medcalfe Bowler” of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Bowler said he was thirty-four years old, and he had left Rhode Island in 1781. (The other fifty or so Rhode Islanders listed in the Book of Negroes left in 1779 or earlier). There was a column for a brief description of the passenger: the clerk thought Arthur a “stout fellow” which in the eighteenth-century denoted sturdiness and strength, not obesity. This clerk’s vocabulary was limited—almost all the men and women on the Nisbet were either ordinary or stout, though one or two were “very ordinary” and some of the children were “likely.” Phebe Bowler, thirty-five, was an “ordinary wench” while their daughter Betsy, twelve, was a “likely girl.” The clerk recorded Phebe and Betsy as being “born free in Portsmouth, Rhode Island.”

Most of the earlier Nova Scotian evacuees landed in Shelburne (then called Port Roseway), which was now overflowing, so the Nisbet was taking its more than one hundred and fifty Black passengers to Port Mattoon, some thirty miles to the north.

About a quarter of the adults on the Nisbet were listed as belonging to the Wagon Master General’s (WMG’s) department. They had been driving the carts hauling British equipment and materiel, an activity vital to the British military operations, but by mid-November the task was nearly done. The Bowlers, however, do not have the initials WMG after their names. The clerk was, perhaps, tired or careless after inserting nearly one hundred and forty names, or the Bowlers were doing something else: many free and self-liberated Blacks worked for the British as laborers, servants or teamsters, or for New Yorkers as carters or carpenters, actors or jockeys, while the women worked as laundresses and servants.[8]

The peace treaty signed in Paris contained clauses instructing the British to return enslaved people to their masters, but Sir Guy Carleton, the British commander-in-chief, felt that anyone who had responded to earlier promises of freedom or who had joined the British before the end of the war, was a free person. He told George Washington he could not honor anything in the treaty “inconsistent with prior Engagements binding the National Honor, which must be kept with all Colours” and to do otherwise would be a “dishonorable Violation of the public Faith.”[9] Washington, whose enslaved stableman Harry Washington was among the newly freed and eventual evacuees, was not best pleased.

As soon as the list was complete, the Nisbet was ready to sail to Port Mattoon.[10]

Fourth clue: The Birchtown Muster of Free Blacks 1784.

The Port Mattoon settlement failed within months, and the Bowlers moved south to Birchtown, a (segregated) Black township near Shelburne. It celebrated Brig. Gen. Samuel Birch, a British officer in New York who had signed many Blacks’ certificates of freedom. The enslaved Blacks and indentured servants stayed in Shelburne with their White Loyalist owners or employers. Birchtown was soon the largest community of free Blacks outside Africa, and almost 1,485 Black Loyalists were there by the time the Bowlers arrived in the early summer of 1784. A close-knit and almost self-sufficient community emerged based around two churches led by formerly enslaved men, the Baptists under David George and the Methodists under blind preacher Moses Wilkinson.[11]

A muster prepared in 1784 lists twenty-one companies in Birchtown, formed for convenience in the distribution of food.[12] Arthur, Phebe and Betsy belonged to carpenter Scott Murray’s company, which comprised forty men, women and children. Eight of the men, including Bowler, described themselves as laborers, a catchall term for anyone without a specific avocation; the company also included two sawyers, a clothier and a cook. It is very unlikely Arthur Bowler had been a laborer when he lived in Newport and Portsmouth, but in the short term there was no call for whatever skills he possessed. As a refugee he was prepared to do anything to survive.[13]

The British originally intended to supply rations for a year but land distribution was slow; clearing old growth forest with only hand tools was even slower, and crops remained unplanted, so the government distributed food for two more years. Later rations were only supplied to those who worked for the community: Birchtown settlers had to perform six days’ labor for the town. This enforced labor was, not surprisingly, a source of tension. Nor was the food particularly appetizing or equally distributed, and before long the Blacks only got meal and molasses to supplement what they could catch or grow.[14]

The free Blacks also faced racial prejudice and they were in a bad bargaining position. White unskilled laborers demanded, and usually received, between two shillings sixpence and four shillings a day, while skilled Black carpenters were willing to work for one shilling a day, and Black laborers earned a mere eight pence, only one third of the White laborers’ wage. The availability and indeed desperation of the free Blacks tended to force wages down, and White working-class men, particularly the demobilized soldiers who were also waiting for their land, resented this. Under such conditions, tempers flared.[15]

Tensions came to a head on July 26, 1784 when there was a “Great Riot” in Shelburne. According to Benjamin Marston, the chief surveyor, “the disbanded soldiers have risen against the Free negroes to drive [them] out of Town because they labour Cheapr [than] they (ye soldiers) will.” The rioting continued the next day when, according to Marston, “The soldiers force the free negroes to quit the Town—pulled down about 20 of their houses.[16]

Baptist preacher David George, who was still living in Shelburne, became the focus of White male fury when he baptized (at her request) a White woman. A mob of more than forty former soldiers swinging chains and ships’ hooks pulled down his house, and then threatened to burn down the Baptist meeting house, but George stood in his pulpit until the protesters began beating him with sticks and clubs and forced him out. He moved his church to Birchtown, where he hoped to be safe.[17] Where Arthur Bowler stood in this uprising is unknown, but as he was in Birchtown, not Shelburne, he may have avoided the violence.

Fifth clue: Land distribution Plan, 1787.

The British had offered land to all the Nova Scotian Loyalists, White and Black, but distribution was slow. In December 1787, four years after he left New York, Arthur Bowler finally got his land. His name appears, along with one hundred and eighty-two others, on a deed which grants him a share of 6,382 acres of Crown land. Most of the grantees received either twenty or forty acres, but Bowler, who was granted Lot 107, received an allocation of thirty-two acres, perhaps because it was awkwardly shaped at the southern end of the grant. As it turned out, he never saw his land as it was some fifteen miles from Birchtown through uncleared forest. Two hundred years later it is a golf course. [18]

Sixth clue: List of those wishing to go to Sierra Leone, 1791.

By the late 1780s British food handouts had ended, the settlers had endured some poor harvests and food was in very short supply. As Boston King wrote in his memoir,

Many of the poor people were compelled to sell their best gowns for five pounds of flour, in order to support life. When they had parted with all their clothes, even to their blankets, several of them fell down dead in the streets, thro’ hunger. Some killed and ate their dogs and cats; and poverty and distress prevailed on every side; so that to my great grief I was obliged to leave Birchtown, because I could get no employment.[19]

Given the problems in Birchtown it is not surprising many villagers were prepared to listen when Lt. John Clarkson, on leave from the Royal Navy, arrived in October 1791 offering to take them to West Africa. Financed by the Sierra Leone Company, and partly inspired by the formerly enslaved Thomas Peters’ visit to London, Clarkson offered to take anyone discontented with Canadian winters and slow land distribution to West Africa. The directors of the Sierra Leone Company were philanthropic evangelical Christians, idealistic eighteenth-century gentlemen. They were also investors and hard-headed merchants, all part of the emerging liberal political economy of the late eighteenth century. Accordingly, they favored trade as a way of “civilizing” and converting the Africans, as well as providing a good return to their shareholders. Eighteen hundred people invested in the Sierra Leone Company, which had working capital of £235,000. The investors included such luminaries as physician Erasmus Darwin, industrialist Sir Richard Arkwright, inventor of the water frame, and Josiah Wedgwood, of pottery fame.[20] While some of the shareholders were altruistic abolitionists, others owned large slave plantations in the West Indies and were looking for new sources of raw materials. All of them expected returns on their investments, which had cost £50 a share, an enormous sum of money, almost a year’s wages for a skilled worker.[21]

Bowler was one of the last to sign up, and one hundred and forty-eight Birchtown heads of households had given their name and their details before he finally went to volunteer. There were only six more Birchtown families to go. He told Clarkson he was a farmer and had a wife and a daughter. He was not yet farming his land, however; he exaggerated slightly and said he had been allocated forty acres but admitted he had not yet seen it. And he did not seem to have the tools to farm it, listing only one axe, two hoes and a spade among the implements of his trade. He did have some other possessions, and told the authorities he would take two chests, two barrels, a bed and a musket on his journey back to Africa.[22]

He was one of fifty-two Birchtown men who said they were born in Africa, while eighty-eight said they were born in the southern colonies, and four born in the West Indies. He was the only one who had been enslaved in Rhode Island. The total number of people amounted to more than five hundred and fifty, rather more than a third of the inhabitants of Birchtown.

Elsewhere in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick many more people signed up, and to Clarkson’s surprise almost twelve hundred people said they wished to leave: he had expected to take about five hundred. He hired extra ships and purchased more provisions, and after several delays, not least by obstructive Whites unwilling to see cheap labor leave, they set sail in January 1792. This was not a good time to be crossing the North Atlantic in small ships – the weather was not kind, and they endured a harrowing eight weeks at sea. When the surviving Nova Scotian passengers arrived in Freetown in March 1792, they found nothing ready for their arrival. The officers and men sent by the Sierra Leone Company had arrived some weeks earlier but rather than set to work, they had stayed quarreling on the (appropriately-named) ship Harpy.[23]

Seventh clue: the Leopard, 1792.

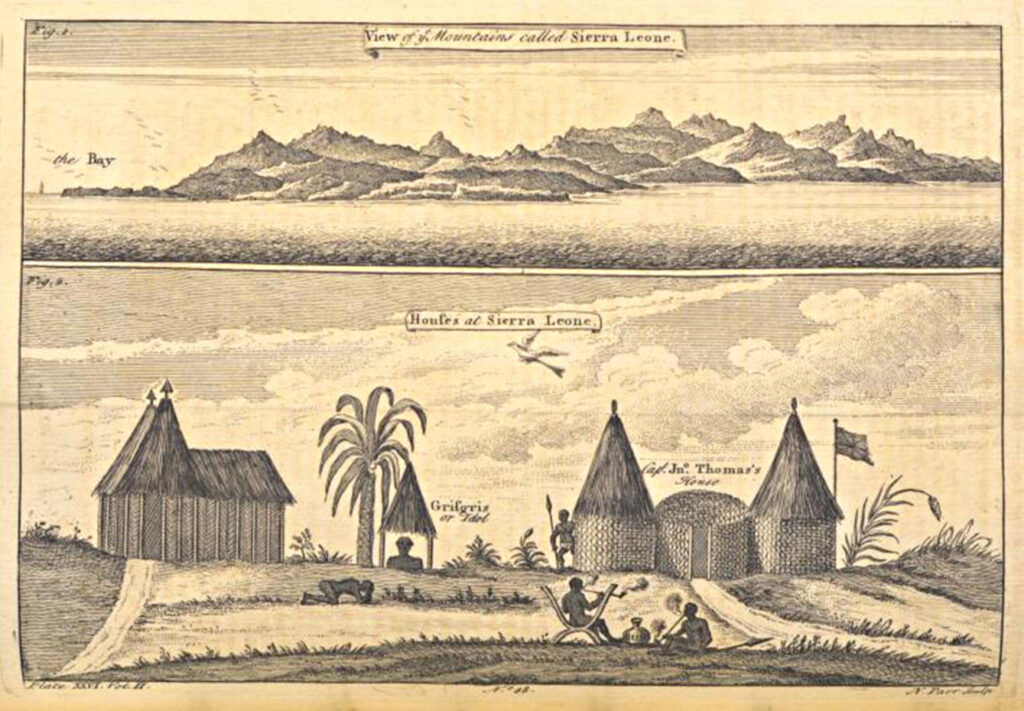

Bowler’s first glimpse of Sierra Leone was of a low, cloud-topped mountain above a sea of green trees. Early Portuguese sailors thought it resembled a sleeping lion, hence the name, the mountain (Sierra) of the lion (Leon). Arthur was probably born elsewhere in Africa, although Bunce Island, some twenty miles upriver from Freetown, was a major British slave castle and had processed the shipment of thousands of captive Africans to the New World.

The local tribes, though not actively unfriendly, were wary, as this was the second attempt to settle former slaves in the area.

Arthur Bowler built a hut, where on March 21 he and his family got a terrible fright. John Clarkson noted the event in his journal, writing:

Early this morning a Leopard came into the streets of the town; one of the colonists Arthur Bowler coming home from a neighbouring thicket, saw the Animal stop at his hut which he had left open and knowing his wife and daughter were asleep, he shouted so loud as to alarm his neighbour and frighten the beast which ran off into the woods. I am much afraid that some of the children will some time or other be carried off by these animals, if they are suffered to leave their huts either early in the morning or late in the evening.[24]

Bowler, like all the other settlers, had a long wait for the surveyor to mark out the farm lots, and the first forty lots (of five acres rather than the promised twenty) were only distributed in mid-November. He had his little hut and a small lot in the town, but he, like most of the settlers, relied for much of his food on supplies from the company store. He had to pay for it by two days’ work a week, clearing brush and building roads, which limited the time available for his own cultivation.

The lack of land spurred the settlers to action. Some of the men fished the teeming rivers with home-made boats, others took their muskets into the forest and hunted antelope and wild boar, fresh meat that would make a welcome addition to the company stores. Some of the far-sighted settlers had brought seeds from Nova Scotia, and pumpkins, beans and cabbage soon sprang up, perhaps sage and thyme flourished, though most of the seeds brought by the company from England failed. The local tribe grew rice, cassava, millet and kola nut, unfamiliar foods that became part of the settlers’ staple diet.

Eighth clue: Sierra Leone Census, 1802.

Arthur Bowler was fifty-three and still in Freetown in 1802 when the British conducted a census. His adult daughter and grandchildren lived with him. The rather judgmental census taker noted in the margin she had “1 Boy and 2 Girls by as many Fathers I suppose.”[25]

There was no sign of Phebe and Arthur was now married to the widow of Richard Richards, a prominent Baptist, who was one of the five “free Ethiopians” from the Halifax area who petitioned John Clarkson for permission to nominate Baptist teachers and preachers from “amongst themselves.”[26] This strongly suggests Arthur was a Baptist, for the religious communities were tightknit.

The two major denominations in Sierra Leone had very different political agendas, and the Baptists were far more accommodating to the British authorities, far less likely to protest what they saw as injustice, than were the Methodists. Governor Zachary Macaulay called the latter “Malcontents.” In one of their letters to Clarkson, back in England, they complained, “We wance did call it Freetown but since your Absence—we have Reason to call it Slavery.”[27]

There were numerous teething problems in Sierra Leone in the decade since Bowler and the other Nova Scotians arrived, though by 1802 many of the sources of friction had ended. Zachary Macaulay, governor of Sierra Leone from 1794 through 1799, began training young Nova Scotians to take over jobs formerly held by Whites. Apothecaries, surgeons, master shipwrights, ships’ captains joined the ranks of Black schoolteachers and preachers, creating a Black middle class invested in the success of the colony.[28] Black militia officers sometimes commanded White soldiers, and Black farmers cultivated new cash crops, notably coffee. It became clear, however, that small farms could not support a family and many Nova Scotians abandoned their yeoman-farmer stance and turned to trade. Those who had received land hired local Africans as laborers, or the Jamaican Maroons (who arrived in 1800) as sharecroppers; after the British abolished the slave trade in 1808, they used Africans “recaptured” from slave ships by the Royal Navy as apprentices or indentured workers. [29]

The Nova Scotians wanted the freedom and self-determination they had long lacked, and wished to be treated as English men and women, with equal rights and privileges, while the directors of the Sierra Leone Company wanted to run the new settlement from London and expected it would yield a financial return for its shareholders. The directors wanted the settlers to plant and harvest cotton, indigo, tobacco, rice and coffee (all of which grew wild) to generate exports to replace the slave trade as a source of income for local tribes and provide a living for the free Blacks growing them. The Company’s desire to generate cash crops grown by free labor in Africa was, however, incompatible with the Nova Scotians’ desire to provide for themselves and their families on their own farms. Most Nova Scotians had been enslaved in the American South and they had no desire to replace plantation labor in Virginia or South Carolina with plantation labor in Sierra Leone. Arthur Bowler, who had probably not been an agricultural laborer during the years he lived in Rhode Island, would have been even less inclined. Only the presence of the respected and conciliatory John Clarkson kept a lid on the simmering discontent for the first year of the settlement. He allowed Blacks to serve on juries with Whites, he allowed women to vote, he listened to their complaints about reserving waterfront property for public buildings. In the absence of roads, access to the water was imperative, and he negotiated a compromise about the size of lots. As one official wrote, without Clarkson “I should scarce think it safe to stay among them.”

The climate was also a problem. Delays in leaving Nova Scotia meant they had arrived at the very end of the dry season, leaving little time to build suitable shelter. The rains began on April 2, 1792 and the hastily built huts proved inadequate.

Between downpours the humidity was debilitating; “nothing made of Steel can be preserved from Rust,” Clarkson wrote, “Knives, Scissors, &c look like rusty iron, our watches are spoilt by rust or laid aside useless . . . everything of linen put by for a time must be frequently aired lest it should mould and rot.” The supplies brought from England rotted in the heat and hunger became an ongoing problem.[30]

Many people fell ill, though the Whites suffered more than the Nova Scotians. More than half the settlers were sick with malaria and “scarce able to crawl about.” Arthur survived: perhaps he had some immunity from his African childhood. Most of the Black settlers recovered, but almost half of the Whites, especially the poorer Whites and the soldiers, died. [31]

In early April 1792 food supplies were running short, and the settlers were put on half rations. Meanwhile the settlers’ “murmurings and resentments” grew as the council member responsible for creating the garden lots was sometimes too drunk to do his job. Festering anger grew, and as one of the councilors noted, “with hunger comes mutiny.”[32]

Thomas Peters, who had been sergeant in the Black Pioneers during the American Revolution, and whose visit to England in 1790-91 partly inspired the Loyalist migration to Sierra Leone, was particularly unhappy. He had a profound effect, particularly on the Methodists, persuading them the officials of the Sierra Leone Company were failing them, just as British authorities had in Nova Scotia. Clarkson sympathized to some extent with the settlers’ discontent, later acknowledging they had been “deceived and illtreated through life . . . and seeing no probability of getting their land, they began to think, they should be served the same way as in [Nova Scotia] which unsettled their minds and makes them suspect everything and everybody.”[33]

On or about April 7, 1792, one hundred and thirty-two people, approximately one quarter of the adult Nova Scotians, signed a petition asking that Peters be their “Speaker-General,” which some interpreted as the people wished to elect Peters as governor.

Clarkson was furious and called all the Nova Scotians to a meeting under a large tree—possibly the large cotton tree that stood in the middle of Freetown until it collapsed in a storm in 2023—and announced, “either one or other of us, would be hanged upon that Tree before the Palaver was settled.” Those of the Nova Scotians who had not signed the petition were confused: they “appeared much agitated not knowing what was the matter.” The Bowlers would have been listening as Clarkson warned that the “Demon of Discord” would bring them “misery and guilt” and, warming to his theme, would hinder the improvement of the Black population throughout the world. He told them the “great anxiety” of the Sierra Leone Company was “to make use of them as instruments to spread the Blessings of Christianity through the wretched Heathen Nations of this vast continent,” and that their actions jeopardized this aim. Whether Bowler or most of the others thought of themselves as “instruments” in spreading Christianity is open to doubt: although their Christian faith was sincere, it is arguable they were equally interested in being treated as men and gaining a competence for themselves and their families.

The settlers tried to explain to Clarkson that they were misunderstood, that they had merely appointed Peters their spokesman, but they eventually agreed to obey the laws of the colony—including the authority of John Clarkson. The grumbling continued, however, as did the influence of Peters, and Clarkson noted in mid-May some of the settlers “imbibed strange notions from Thomas Peters as to their civil rights.”[34]

Where Arthur Bowler stood in this challenge to Clarkson’s authority is not known: the original petition does not survive so the names of the one hundred and thirty-two complainants are lost, but many of them would have been Peters’ supporters from Annapolis and New Brunswick, or Methodist followers of Boston King and blind preacher Moses Wilkinson. The Baptists under David George’s leadership were more moderate, more inclined to support Clarkson.

Conclusion

Arthur outlived his former enslaver who died in poverty in Providence, Rhode Island, but not in disgrace: Metcalf Bowler spied for the British before returning to the Patriot side, but his treachery was not discovered until the 1920s.[35] His gravestone in St. John’s burying ground in Providence is ironic, saying it was:

Sacred to the Memory of the Hon. Metcalf Bowler Esq., who resigned his soul to God on 19th September 1789 in the 63rd year of his age. Having been repeatedly elected to several of the most important offices in this State, shows the confidence of the Public in his ability and Patriotism, and is the best eulogium of his Character. He served as Judge of the Superior Court, was 19 years speaker of the lower House of Assembly and was a member of the 1st Congress in 1768 the duties of which station he discharged with Honor and Ability.

Arthur, whose journey took him from Africa and back, was a free man after twenty years of enslavement, eight difficult years in Nova Scotia and an early encounter with a leopard.

Historian Ellen Gibson Wilson concluded that there were always two Freetowns. The Sierra Leone Company’s experiment failed and the country became a British colony, but she believed it was a triumph for the realization of the Nova Scotians’ wishes and dreams. Although the new life was hard, it was, she said, “immensely more challenging, exciting, and influential” than the lives they left behind. Even Henry Thornton, the guiding light behind the Sierra Leone Company, suspected this, saying some “happy consequences” may have emerged and “tho’ I have lost £2000 or £3000 . . . I am on the whole a gainer.”[36]

Arthur was a gainer, too.

[1] For a use of small clues to build the story of a life see Tiya Miles, All that She Carried: The journey of Ashley’s sack, a Black family keepsake (New York: Random House, 2021). And for a brilliant account of an obscure life, see Linda Colley, The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A woman in world history (New York: Pantheon, 2007).

[2] Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway slaves of the American Revolution and their global quest for liberty (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006); Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the slaves and the American Revolution (New York: Harper Collins, 2006); Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American loyalists in the revolutionary world (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011). A vital source is Graham Russell Gao Hodges, The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in exile after the American Revolution (New York: Garland Library of the Humanities in Association with the New England Genealogical Society, 1996).

[3] Cesar Lyndon, “Account and Memorandum Book,” Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, RI, MSS 9004, v.10, pp. 82-84.

[4] Jared Ross Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and dependence in eighteenth century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 54-55.

[5] Vernon Family Papers, Box 49A Folder 12, Bowler, Metcalf, Newport Historical Society. The house at 46 Clarke Street, Newport, now known as the Vernon House, is a national historic landmark; it was Rochambeau’s headquarters during the French occupation, and George Washington dined there.

[6] There are two original copies, with significant difference; the copy in the US National Archives contains 2,555 names, while the British copy contains 3,000, which includes the 407 who were still enslaved. See www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/loyalists/book-of-negroes/Pages/introduction.aspx.

[7] www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Trails/2018/Loyalist-Trails-2018.php?issue=201836.

[8] Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), chapter 15.

[9] William Smith, Historical Memoirs of William Smith, 1778-1783 (W.H. W. Sabine, ed. New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1971), 574, quoted in Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 89.

[10] See Hodges, The Black Loyalist Directory.

[11] Schama, Rough Crossings, 226, Walker, Black Loyalists, 43.

[12] Muster Book of Free Black Settlement of Birchtown,” 1784, Library and Archives Canada, MG 9 B9-14, item 1292, www.blackloyalist.info/event/display/8.

[13] Birchtown Muster, www.blackloyalist.info/event/display/8.

[14] Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 357, 160; and Walker, Black Loyalists, 32, 40, 44-45.

[15] Walker, Black Loyalists, 46-7, 62.

[16] Wilson, The Loyal Blacks, 92.

[17] Diary of Benjamin Marston, 26-27, 1784, blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/marston_journal.htm.

[18] Bowler’s Land Allocation appears in the Nova Scotia Land Papers 1765-1800 RG-6052-6, Nova Scotia Archives Halifax, NS, novascotia.ca/archives/landpapers/archives.asp?ID=1080&Doc=document&Page=201108174.

[19] Autobiographical memoir of Boston King, a fugitive slave from South Carolina who became a teacher and minister in Sierra Leone, serialized in 1798 in The Methodist Magazine, blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/king-memoirs.htm.

[20] Suzanne Schwarz, “A Just and Honourable, Commerce: abolitionist experimentation in Sierra Leone in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,” 6, eprints.worc.ac.uk/5308/1/Lecture%202013%20PressRevised%20%281%29.pdf.

[21] The sum could buy four horses or ten cows in 1790; www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result.

[22] The list of Blacks in Birchtown who gave their names for Sierra Leone in November 1791 appears at www.blackloyalist.info/source-image-display/display/114.

[23] See Clarkson’s Mission to America 1791-92, edited with an introduction by Charles Bruce Ferguson (Halifax NS: Public Archives of Nova Scotia, 1971), 2:67, 92. A transcript of John Clark’s journal is “Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People,” Canada’s Digital Collection http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/mission.htm.

[24] Lt. John Clarkson Diary (19 March 1792 – 4 August 1792), University of Illinois, Chicago. Special Collections, Sierra Leone Collection, Box 1, Folder 4. My thanks to Suzanne Schwarz, University of Worcester, for this and other Sierra Leone references. Clarkson, Mission to America, 2:9.

[25] 1802 Freetown Sierra Leone Census, The National Archaives, WO 1/352.

[26] See blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/mission.htm.

[27] See Wilson, The Loyal Blacks, 321.

[28] He was father of Thomas Babington Macaulay, the historian. See Catherine Hall, Macaulay and Son: Architects of empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

[29] See Walker, The Black Loyalists, 260-61.

[30] Pybus, Epic Journeys, 153-54; Clarkson, Mission to America 2:72; Rachel B. Herrmann, “Rebellion or riot? Black Loyalist food laws in Sierra Leone,” Slavery & Abolition, Vol. 37 no. 4 (2016), 680-703.

[31] Walker, Black Loyalists, 158-159n6, quoting the Sierra Leone Company’s Directors’ Report, 1794, 45-47.

[32] Mortality figures from Walker, Black Loyalists, 159n6, quoting Clarkson papers IV and Dr. Taylor’s diary, April 11, 1792; Councilor James Watt to Clarkson, April 27, 1792, quoted in Walker, The Black Loyalists, 149.

[33] Clarkson, Mission to America, June 15, 1792, quoted in Pybus, Epic Journeys, 153 and Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 297.

[34] Clarkson, Mission to America 2:80-87, quoted in Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 298, and n66; see also Pybus, Epic Journeys, 152-53, Walker, Black Loyalists, 151, and The Philanthropist Vol. V (1815), 35.

[35] See Jane Clark, “Metcalf Bowler as a British Spy.” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, Vol. XXII, no 4 (October 1930).

[36] Thornton quoted in Wilson, Loyal Blacks, 407.

2 Comments

Excellent article, thanks so much!

Thorough article, considering the time trip it is on and the subject was a common man (a common black man).