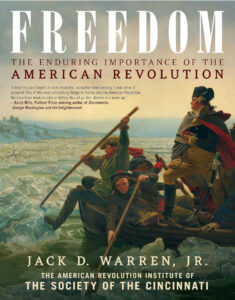

BOOK REVIEW: Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution by Jack D. Warren, Jr. and the American Revolution Institute of The Society of the Cincinnati (Essex, CT: Lyons Press, 2023. $59.95 cloth)

George Washington walked away from power when he resigned his commission to the Continental Congress in December 1783. King George III, on hearing that Washington might do such a thing, said “‘If he did that, he would be the greatest man in the world.’” (page 280) This action sealed Washington’s legacy as the American “Cincinnatus,” the Roman leader who turned down dictatorial power in order to return to his farm. Before he left the army, Washington’s officers formed the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization that allowed for them to gather to share their experiences and to help each other when necessary. One final commitment for the Society was to remind Americans “to remember and honor the achievements of the Revolution.” (p. 269) The book Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution, written by Jack D. Warren, Jr. and put out by the Society, is an excellent reminder of the values and ideas of the Glorious Cause.

Freedom chronicles the events of the Revolution from the colonization of British North America through the ratification of the Constitution. The focus throughout the book is the concept of “freedom.” What did it mean? How did the idea come about in the colonies? The Prologue sets the question which the book tries to answer: “Why is America Free?” First, the author looks at what freedom meant in Britain. People migrated to North America partly for this idea, whether it was economic freedom or religious freedom. The first section of the book, “British America,” analyzes how and why North America was colonized by Great Britain. The French and Indian War was a result of Britain’s competition with other European powers in North America. The second section, “The Shaping of the Revolution,” details the taxation policies of Parliament, colonial resistance, and the intolerable British response. The familiar figures are all there: Washington, Henry, Wheatley, Adams, Franklin, and Warren.

Freedom chronicles the events of the Revolution from the colonization of British North America through the ratification of the Constitution. The focus throughout the book is the concept of “freedom.” What did it mean? How did the idea come about in the colonies? The Prologue sets the question which the book tries to answer: “Why is America Free?” First, the author looks at what freedom meant in Britain. People migrated to North America partly for this idea, whether it was economic freedom or religious freedom. The first section of the book, “British America,” analyzes how and why North America was colonized by Great Britain. The French and Indian War was a result of Britain’s competition with other European powers in North America. The second section, “The Shaping of the Revolution,” details the taxation policies of Parliament, colonial resistance, and the intolerable British response. The familiar figures are all there: Washington, Henry, Wheatley, Adams, Franklin, and Warren.

“The Glorious Cause,” the third section, begins with the outbreak of war at Lexington and Concord. The colonies found themselves in the middle of a true civil war. By 1776, the colonists started to see the advantages of separating from the mother country, and the resulting Declaration of Independence explained the need for government and the rationale for revolution. The idea of equality is presented, although Jefferson may not have really understood the future of this idea. And the embrace of the concept of freedom forced Americans to deal with the hypocrisy of slavery. In “Republics at War,” states started to create their own constitutions so that they could be a part of a new republic. What rights would the people have in the states? Were they for all people? The French alliance, Saratoga, the war in the South, and the final battle at Yorktown are given their due in this section, and the reader meets Lafayette, Burgoyne, Cornwallis, Greene, Tarleton, John Paul Jones, and Hamilton.

The fifth section, “Independent America,” begins with the peace negotiations in Paris and the tension that still existed in the new nation. What would peace look like? Could the republic be maintained? The Articles of Confederation were governing the states, albeit weakly. Along with western land disputes and continuing conflicts with various Indian tribes, Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts demonstrated the need for a stronger national government. The Constitution was written in Philadelphia in 1787, but how were people to be given a voice in the new government? If slaves were 3/5 of a person, how did that affect the concept of freedom that was at the heart of the Revolution? The book’s Epilogue briefly covers the unfortunate reality of political factions emerging during the fight for ratification. Luckily the states came together in the end, and the American experiment started as a “’leap in the dark,’” according to Jonathan Smith. (p. 354) The last picture in the book shows a young Goddess of Liberty lifting a cup to feed a young bald eagle. The final sentence of the Epilogue, juxtaposed facing the painting, is perfect: “The idealism of the Revolution is the foundation of our freedom and the hope of people who long for freedom in every part of the world.” (p. 356)

Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution is a valuable work of scholarship. Written in a plain and easy narrative, the book is a visual treasure. Almost all the familiar portraits and well-known paintings that historians would easily recognize are there, on large pages and in color. One could ignore the text and simply lose oneself in the images in the book.

After the Epilogue, Warren included a section called “A Note on Names,” in which he explained why he used, or did not use, certain names for groups of people throughout the book: migrants, indentured servants, liberals, Indians, slaves, etc. This section would have been much more useful had it been at the beginning. Especially important in this section is a comment on slavery, included here in full:

We have termed people held in perpetual bondage as enslaved people rather than slaves. We have used slave and slavery to refer to legal status and to the institution, but we draw a line at referring to people as slaves, a term that subordinates their individual identities and defines them solely in relation to their oppressors. The American Revolution challenged the idea that enslavement was morally or ethically just and led to its ultimate demise. A work aimed at encouraging understanding and appreciation of the constructive accomplishments of the Revolution should embrace one of its most important: the insistence that all men are created equal and possess the same natural rights. Those rights belong to all of us, men and women, as individuals, and the way we refer to one another, living and dead, should reflect that fact. [p. 359]

PLEASE CONSIDER PURCHASING THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON IN CLOTH or KINDLE. (As an Amazon Associate, JAR earns from qualifying purchases. This helps toward providing our content free of charge.)

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...