Very early on a hot summer’s day in 1778, Moses Mather, Jr., son and namesake of the Patriot minister of Middlesex Parish (today’s Darien), Connecticut, was seventeen years old and sitting in a whaleboat just offshore.[1]

Only two years before, whaleboats rarely had been seen in western Long Island Sound. But as enemies on both sides of the water realized how easily the craft could be converted from sailing to rowing and back again, or dismasted and stealthily carried up beaches to be hidden in the underbrush, by early 1778 their numbers had multiplied. In late March a New York newspaper reported uneasily, “We hear a number of rebel whale boats have been seen reconnoitering the north shore of Long Island.”[2] By May Connecticut whaleboats had been plundering Long Island and capturing Loyalists and small British vessels for weeks.

On the morning of June 24 it was cloudy and airless by 5:00 AM, not a breeze stirring. There were five Connecticut whaleboats floating west of the Norwalk Islands, and it appears the men in them were bored.[3] Someone must have had a spyglass.

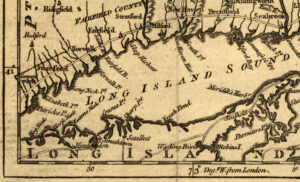

A becalmed sloop was spotted close to the Long Island shore beneath the cliffs of Lloyd’s Neck, a peninsula halfway between Huntington Bay and Oyster Bay. Loyalist refugees there supported their families by cutting firewood for the British military. The wood was loaded on small sloops and schooners that were escorted by armed vessels in groups to New York. Here was a solitary wood sloop, helpless.[4]

Thomas Painter, eighteen years old and in a whaleboat from New Haven, later recalled in a memoir written for his children, “In a short time someone proposed to go over and take that Sloop and tow her across the Sound. No sooner said, than it was agreed to by all hands.”[5]

The decision was the height of daredevilry. Within a five-mile stretch the boys could also see riding at anchor three British sloops-of-war, the Falcon, Raven, and Swan, all of fourteen guns, and the brigs Halifax and Diligent of ten guns. Moreover, inside Huntington Bay lay the powerful twenty-four-gun frigate Fowey.[6] The raiders were gambling that they could dart in, seize the little sloop, and tow her away while the enemy ships lolled powerless without a breeze.

Unfortunately, sometime after 7 AM someone on the Diligent spied the five whaleboats approaching the wood sloop. Immediately her commander, Lt. Thomas Farnham, ordered two of the brig’s 3-pounders fired to alert the rest of the British squadron. The Raven acknowledged the warning by firing two guns of her own.[7]

Lighthearted, the whaleboatmen decided they were still committed. “we were quick at our oars, going for the Sloop,” said Painter, “notwithstanding there were several Ships of War, lying in Oyster Bay, all in plain sight, and we in plain sight of them and they preparing and manning their boats to oppose us. But notwithstanding all this, Over we went—took the Sloop—and towed her with our boats, after having put about three men from each boat aboard the Sloop, to fight the boats which were coming up after us.”[8]

They had hit a hornet’s nest with a stick. Soon the enemy was swarming from all directions. Ships’ boats, manned and armed, were launched from every British vessel in the area—the Diligent, Halifax, Falcon, Swan, Raven, and Fowey—quickly joined by Loyalist whaleboats from Oyster Bay. Painter recalled, “The boats coming up after us, were about 18 in number, and probably not less than 150 men.”[9]

Painter and his captain, Elisha Elderkin, both experienced privateers, were two of the roughly ten men now on the captured wood sloop. “The Sloop having some Swivels on board, we made free use of them,” Painter recalled.[10] The rest of the whaleboatmen bent to their oars, rowing with all their might. The ropes towing the sloop were taut.

Off Oyster Bay, the Diligent had made sail. With little wind, her progress was slow. Nevertheless she crept after them, her cannons firing twenty-one 3-pound shots at the fleeing whaleboats and their prize. The eighteen British boats were rowing furiously in chase. Meanwhile the raiders aboard the towed sloop blasted astern with their purloined swivel guns. Capt. John Stanhope of the Raven noted in his log the Americans’ “very hot fire.”[11]

The boats churned across the Sound. The Diligent was eventually left behind. Hours passed, men sweated in the muggy heat, and the overcast sky grew darker, as if a storm were approaching.[12] It seems the frantically rowing oarsmen on both sides were too focused to notice. It was the beginning of a solar eclipse.

At 9 AM British muskets began firing in earnest as the gap between hunters and quarry narrowed. Still, the five whaleboats towing the wood sloop were nearly across the Sound to safety at Stamford when they finally fell within range of the eighteen pursuing boats. There was an eruption of crossfire. “notwithstanding their superiority,” Painter said, “we beat them off, on the first attack, and got the sloop almost over to the main.”[13]

A visiting Rhode Island privateer sloop, the General Arnold, came out of Stamford harbor to their aid, accompanied by a privateer schooner, the Mehitable, under Capt. Daniel Jackson of Wilton Parish, Norwalk. Both were small coastal vessels, only twenty-five and ten tons burden respectively, and in the faint wind neither could move nimbly, but together they brought nine more swivel guns and two 2-pounders to the fight.[14]

At 10 AM for several minutes the dim light was swallowed in an eclipse of 93 percent totality. The boat fight raged on. Fifteen miles away in Fairfield, the Rev. Mr. Andrew Elliot and others were straining to see what was happening. He wrote to his father, “During the late Eclipse of the Sun we heard an incessant firing of Cannon and small Arms . . . the sky was so dark—the Air so thick that we were not able with our best Glasses to discover the Cause.”[15]

It seems at least one of the enemy boats was sunk. The British and Loyalists briefly fell back. However, even as the sky gradually lightened, “they rallied and came up the second time, and rowed right alongside of the [stolen] sloop,” Painter wrote.[16] Enemy muskets were blazing at point-blank range.

At this the men in the Connecticut whaleboats panicked. Four of the five “cut their tow lines and ran of[f] and left us,” Painter recalled bitterly in his pension application.[17]

The panic spread. On the General Arnold, twenty-four-year-old Capt. Paul Cartwright went over the rail to escape, as did some of his crew. On the Mehitable, Capt. Daniel Jackson battled on, but it seems three of his men may have abandoned the fight.[18]

Why didn’t the last whaleboat flee? Conscience, exhaustion, or were there grievously wounded men aboard? The result was the same. The wood sloop was now helpless to move. Without wind, their crews depleted, the privateer sloop and schooner weren’t in much better shape. Soon they were surrounded, and the British boats “attacked with the greatest fury.” Shortly after 11 AM, the wood sloop, the two privateers, and the whaleboat all surrendered.[19]

By early afternoon, the enemy had shepherded all prisoners and prizes back to Huntington Bay. The weary Americans were taken aboard the ship Fowey, where they were threatened with hanging at the yardarm. “Thus ended our Whale Boat Cruise,” wrote Painter, “and a more foolish and fool hardy transaction is not to be found upon record[.]”[20]

In fact, the escapade was so completely hare-brained that both sides tried to ascribe a logical motive. In New York, the Royal Gazette declared that the whaleboats were attempting an attack on the woodcutters at Lloyd’s Neck when they were cut off by boats manned by a detachment from DeLancey’s Brigade—which also had seized two armed rebel brigs covering the assault. The competing paper stated that in their effort to attack the woodcutters at Lloyd’s Neck, the whaleboats had been convoyed by the Wild Cat galley and a tender recently captured from the Raven sloop-of-war. Meanwhile, in Connecticut, Andrew Eliot assumed the whaleboats had been returning from a trip plundering civilians on Long Island, referring in disgust to “their shameful Voyage.”[21]

Just what had been the cost of this impulsive lark to steal a low-value wood sloop? The sleepy morning had exploded into a barrage of cannon fire and musketry, “a smart engagement of several hours.” In his log, Capt. John Henry of the Fowey recorded that twenty-five Americans were captured and twenty-three killed. This tallies closely with Eliot’s initial information that forty-four Americans were killed, wounded, or missing. A week after the fighting the Connecticut Journal reported, “We lost 24 Men, 5 or 6 of whom are supposed to be killed or wounded.” It seems impossible to discover exactly how many American casualties there were. (On the British side, “we had not One man hurt,” Captain Henry noted with satisfaction.) How many of the prisoners taken up onto the Fowey were wounded? Was Captain Henry given a miscount, or did two prisoners die of wounds overnight? What is clear is that the next morning, twenty-three American prisoners, guarded by seven marines, were transferred from the Fowey to the sloop-of-war Falcon.[22]

Most of this little band of prisoners did not know each other. Since Elderkin’s New Haven whaleboat had been one of those to cut its tow-line and escape, neither he nor Thomas Painter recognized anyone in the group. It seems likely that Moses Mather of Darien had been among those in the staunch last whaleboat. There were Rhode Island men from the General Arnold, and Fairfield County men and Long Island refugees from the Mehitable. And sprinkled among them were three boys under the age of sixteen.[23]

All week the cloudy, breathless weather persisted, punctuated by heat lightning. The Falcon moved ponderously toward New York, its boats “towing and rowing the Ship up Sound” to Hart’s Island, where the prisoners were put on a tender for the city.[24]

Five days after their capture, the group was delivered to the prison ship Good Hope, anchored in the mouth of the Hudson River off the western edge of Manhattan, not far from the Cortlandt Street ferry stairs. During their incarceration the prisoners would hear the ferry to New Jersey pass first on one side of the ship, and then the other.[25]

If any man put aboard a prison ship could be considered to have luck, they were lucky. The Good Hope was a new prison ship. Formerly a Danish merchantman, a cargo ship of 700 tons burden, the Good Hope had been captured by the British in the Chesapeake, brought to New York, condemned as a prize in a Court of Admiralty, and sold to a private owner. The rental agreement was less than two weeks old. She had not yet been hulked, and, more critically, when they arrived June 29, she was not yet crammed and festering with sick prisoners.[26]

Nevertheless, thought Thomas Painter, she soon would be. “considering that I had not had the Small Pox, and that most likely it would soon be on board,” he recalled, “and considering also that the Chance of our Exchange was Extremely bad, on account of our being Whale boat men (the worst kind of Privateers men), It therefore seemed to me, as if some way of Escape must be contrived.” The plucky eighteen-year-old had already urged the group to make a break for it. As the Falcon’s tender was threading the Narrows between Brooklyn and the city, the marine guards had lounged carelessly, and Painter was sure they could be overpowered. However, most of his fellow prisoners refused to try.[27] Perhaps the result of their last rash decision weighed heavily.

In his memoir and pension testimony Painter never mentioned casualties. But he definitely didn’t aim to be one of them.

Soon the quick-witted young man had a plan that he shared with his captain, Elisha Elderkin. Each evening the prisoners were locked in the hold while the guard rested in their quarters between decks and two sentinels patrolled above. After sunset prisoners were allowed in pairs up through a narrow grated hatchway onto the deck for air. Painter had a junk bottle (a quart-sized bottle of thick dark glass). Perhaps if they both saved their small daily ration of rum they could collect enough to make the sentinels too drunk to notice them slip into the Hudson. They could swim to the jolly boat tied to the Good Hope’s buoy, and once the tide carried them silently away from the anchored ships, they could row to safety. Elderkin immediately agreed.[28]

It took two or three weeks of scrimping to fill the quart bottle and to wait impatiently for a moonless night. At last the moment arrived. Everything proceeded according to plan. As the level of rum in the bottle diminished, the two sentinels became more and more “good Natured” and “happy,” until they were paying no attention to duty—or to the grate securing the hatchway. More prisoners streamed up from below. Heels began thudding on the deck as desperate men scrambled up on the gunwales of the ship to jump into the Hudson or to climb down the anchor cable. Painter became separated from Elderkin in the noisy confusion, but he, too, leapt from the cable into the water. He estimated that seven men were swimming for their lives in the darkness when the guards burst on deck and sounded the alarm.[29]

Fleeing prisoners were seized on the gunwales and while clinging to the anchor cable. The nearby ships helped scoop swimmers from the dark water. In the end, only Painter made his escape.[30] All the rest were quickly back aboard the Good Hope—where they sweltered.

The heat on a prison ship in a humid New York summer was torture. Robert Sheffield of Stonington had spent six days on one in early June. “The steam of the hold was enough to scald the skin and take away the breath, the stench enough to poison the air all around.” That spring four prison ships at New York were jammed with skeletal men and disease was rampant. “The heat was so intense that (the hot sun shining all day on deck),” he reported, the prisoners were “all naked,” many delirious, “all panting for breath.” When Rear Adm. James Gambier arrived to take command at the end of May, men aboard the Judith prison ship sent him a petition on June 12 enumerating their distresses in horrific detail. The admiral promptly responded that he had “ordered a large commodious ship to be got ready immediately for the reception of the masters, mates, and gentlemen passengers—and another ship will be got ready in a few days, to thin the numbers on board of each prison ship, and to separate the well men from the sick.” Three days later the rental papers were signed for the Good Hope.[31]

But if those in the hold of the Good Hope had (at least for a time) thinner numbers and (for a time) less exposure to disease, little could be done about the heat. It had been near 100° F at the end of June. After a July fortnight on the ship, Painter had been almost naked and it’s likely the rest of his companions were also. In August a thermometer read in the nineties in the open air.[32] Conditions below decks would have been brutal.

Once again the prisoners captured at Stamford had something approaching luck. They had endured approximately five suffocating weeks on the Good Hope when details of a long-discussed cartel were finally hammered out. In early August the New York papers published a notice: “[A] general Exchange of American Marine Prisoners is now agreed on . . . 200 are already sent to Elizabeth-Town [New Jersey] . . . all those remaining, as well on Parole as in the Prison Ships, will be sent there by Thursday next the 13th Instant.”[33]

In fact, the prison ships could not empty quite that quickly. According to a New London report of September 25, “All the American prisoners are nearly sent out of New-York, but there are 615 French prisoners still there.” Records show that most of the twenty-two remaining Stamford captives were discharged from the Good Hope to various cartel vessels during the last week of August. Capt. James Sawyer and the boy Abraham Cooper had to wait until September 20. Capt. Daniel Jackson was released in October. The health of any of them was not recorded, nor how or when any reached their homes. But all survived imprisonment.[34]

Among those whose later careers can be traced, Daniel Jackson, gunner Jonathan Seymour, and seaman Richard Provost of the Mehitable would serve together again the following year under Capt. David Hawley on the Connecticut armed sloop Guilford. Thomas Provost joined the artillery at Stamford. Elisha Elderkin of New Haven returned to the boat service, taking prizes on the Sound with his armed whaleboat True Blue. The ever-resourceful Thomas Painter served at sea and on land. In July 1779, less than a year after the discharge from the Good Hope, a party of Loyalists crossed the Sound in a whaleboat and broke into the Darien home of the Patriot minister Moses Mather, Sr., described in a royalist paper as “a mischievous Puritan Priest . . . [who] from his Pulpit bitterly inveighed against his sovereign,” carrying him off to New York along with four of his sons. This time luck was not with Moses Mather, Jr. Eight weeks later he died of disease in one of the city prisons at age eighteen.[35]

Although previously whaleboats had made the occasional appearance, the spring of 1778 had marked the true beginning of Long Island Sound’s whaleboat war. That summer the number of boats on both sides skyrocketed. By August, George Washington put Lt. Caleb Brewster in command of a Continental whaleboat for intelligence work, just as in New York William Tryon commissioned Connecticut refugees to spy in whaleboats for Britain. By 1781 both the Patriot coast of Connecticut and the Loyalist northern shore of Long Island would be described as “infested” with whaleboats.[36] They were in constant use for privateering, raiding, plundering, kidnapping, and smuggling. For five years men would fight ferociously and often die in whaleboat battles on the Sound.

The madcap, reckless snatching of a wood sloop and the ensuing “smart engagement” at Stamford were merely notes in the prelude.

[1] Prisoner list: Muster-Table of His Majesty’s Ship Falcon, June 25, 1778, Great Britain, The National Archives (TNA), ADM 36/B016, courtesy of Todd W. Braisted.

[2] New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, March 23, 1778.

[3] Weather from logs of His Majesty’s ships Fowey, ADM 51/375, Falcon, ADM 51/336, and Raven, ADM 51/771, and armed brigs Diligent, ADM 51/4163, and Halifax, ADM 52/1775, all TNA. Location of whaleboats: Thomas Painter, Connecticut, No. R6896, Collection M-804, Pension and Bounty Land Application Files, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter Pension Files); number of whaleboats: ibid., and Thomas Painter, Autobiography of Thomas Painter: Relating His Experiences During the War of the Revolution, privately printed, 1910; 20 (hereafter Autobiography). Painter’s pension application and autobiography differ. Fowey, Diligent, and Falcon logs specify 5 whaleboats. In his autobiography Painter adds confusion by mentioning the schooner but according to period sources she wasn’t involved until later.

[4] It was identified as a wood sloop in Raven log, ADM 51/771, TNA.

[5] Painter, Autobiography, ibid.

[6] Ships listed in Records of the British New York Vice-Admiralty Court, Captured Ship: Mehitable, (Captured Ship: Mehitable) HCA 32/338/14/1, TNA.

[7] Diligent log, ADM 51/4163, TNA, Raven log, ADM 51/771.

[8] Painter, Autobiography, ibid.

[9] Ships allowed a prize share are listed in Captured Ship: Mehitable, ibid. Loyalist boats from Oyster Bay in Diligent log, ADM 51/4163, TNA; they are identified as from DeLancey’s Brigade in Royal Gazette (New York), June 27, 1778. Boats coming up: Autobiography, ibid. Jackson in Daniel Jackson, Connecticut, No. S17512 (Pension Files), testified to eighteen boats.

[10] Roughly ten: Painter (Pension Files). In his pension application, Painter stated “2 or 3;” in his autobiography, “about three.” Yet there were only two from his boat and it is hard to believe each of five boats contributed three men to fight a few swivel guns, leaving all boats shorthanded.

[11] Logs of Diligent, ADM 51/4163 and Raven, ADM 51/771, both TNA.

[12] Grew darker: the moon’s disk began crossing that of the sun at 8:48 AM. Eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak, EclipseWise.com, eclipsewise.com/solar/SEcirc/1701-1800/SE1778Jun24Tcirc.html#section3.

[13] At 9 AM: Two log entries of Diligent, ADM 51/4163; Michael J. Crawford, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (NDAR), Vol. 13 (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2019), 193, transcribes this entry, “from 9 to 11 Continued fireing Musquestry;” it is “Continuel.” Diligent was far out of range, as is later clear: “at Noon the armed Boats & Prize Vessels Joind Us off Loyds Neck.” Farnham was describing the musketry of the boats.

[14] Came out: reconstructions, including eighty-six-year-old Jackson in Daniel Jackson (Pension Files), put them at Huntington, but period records are clear they were captured off Stamford. Falcon log, ADM 51/336, TNA, specifies both emerged from Stamford harbor at 10 AM. Guns: Captured Ship: Mehitable, ibid; Captured Ship: General Arnold, (Captured Ship: General Arnold), Records of the British New York Vice-Admiralty Court, HCA 32/338/14, TNA. Both had most recently been in Greenwich.

[15] At 10 AM: Eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak, EclipseWise.com. “Late Eclipse”: Andrew Eliot, Jr. to Andrew Eliot, Sr., June 26, 1778, in Bernadine Fawcett, Missing Links to the Culper Spy Ring? (Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing, 2005), 203.

[16] The moon’s disk moved off that of the sun completely at 11:20 AM. Eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak, EclipseWise.com. Andrew Eliot mentioned “boats” sunk but as logs for Diligent and Raven clearly state five stole the sloop, four cut their tow lines, and one was captured, any boat sunk must have been the enemy’s; Fawcett, Missing Links, 203. They rallied: Thomas Painter, Autobiography, ibid.

[17] Ran off: Painter (Pension Files).

[18] Capt. Paul Cartwright: in Captured Ship: General Arnold; the sloop’s papers indicate a crew of twenty-five; there were only eight (seven men and a boy) when she was taken. In Captured Ship: Mehitable, Daniel Jackson testified that there had been thirteen hands, officers included, but this was changed to “ten” “when she was taken.” How many had been aboard either when the action started is unknown, as is the number killed.

[19] With greatest fury: Andrew Eliot in Fawcett, Missing Links, 203; 11 AM: log of Diligent, ADM 51/4163.

[20] Threatened: Painter (Pension Files) and Painter, Autobiography, 21.

[21] Attack on the woodcutters: Royal Gazette, June 27, 1778; competing paper: New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, June 29, 1778; shameful Voyage: Andrew Eliot in Fawcett, Missing Links, 203.

[22] Smart engagement: Connecticut Journal, July 1, 1778, Capt. John Henry: Fowey log, ADM 51/375; This tallies: Andrew Eliot in Fawcett, Missing Links, 203; We lost: Connecticut Journal, July 1, 1778; not one man: Fowey log; twenty-three prisoners: Muster-Table of His Majesty’s Ship Falcon, ADM 36/B016, TNA, courtesy of Todd W. Braisted; marines: Falcon log, ADM 51/336, TNA; New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, June 29, 1778, said, “Thirty Men were made Prisoners, and two killed, without any Loss on our Side.” Did these two die on the Fowey?

[23] Muster-Table of His Majesty’s Ship Falcon, ADM 36/B016; Muster-Table of His Majesty’s Ship Ardent, ADM 36/7824, TNA, courtesy of Todd W. Braisted. The twenty-three prisoners were listed on the Falcon and then again, some with descriptions, on the Ardent: Wm. Havens, Master; Wm. Johnson, Mate, John Dunwell, Lieut.; Palmer Cleveland, Boasn.; Jno. Finch, Sr. Mate; John Sweet, Seaman; Geo. Havens, Boy; Daniel Jackson; Jna. Seymour, Gunr.; Isaac Raymond, Clk., Saml. Conclin, Seaman, Moses Mathers; Thos. Provoce; Richd. Provoce, Seaman; Peter Stonard; Jno. Thatcher, Boy; James Sawyer, Captn.; Benjamin Stonard or Leonard, Seaman; Jno. King; Abm. Cooper, Boy; Thomas Painter, Elisha Elderkin, Master. Painter and Jackson were listed on Falcon but not on Ardent. Painter escaped; Jackson testified July 1 at New York’s Vice-Admiralty Court. In his pension he said he was imprisoned on the Prince of Wales prison ship; perhaps he was returned there instead of the Good Hope.

[24] Falcon log, ADM 51/336, TNA.

[25] Painter, Autobiography, 21.

[26] New: Painter, Autobiography, 21; Danish of 700 tons: British New York Vice-Admiralty Court, Captured Ship: Good Hope, HCA 32/344/2/1-25, TNA; sold: Royal Gazette, May 13, 1778; rental: Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714-1792 (Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing, 2007), 353, courtesy of Three Decks, www.threedecks.org. Winfield records the first rental agreement, June 16 to August 15, 1778. Not yet hulked: a year later, her sails and rigging, masts, spars, and yard were advertised for sale by Thomas Ludlow, Jr. New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, August 8, 1779. On April 24, 1780, Vice-Adm. Arbuthnot recommended discharging the Good Hope, ADM/106/1255/92, but on March 5, 1780, her prisoners, wrote Naval Commissary General David Sproat, “wilfully, maliciously and wickedly burnt the best prison ship in the world.” New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, February 12, 1781.

[27] Painter, Autobiography, 22.

[28] Ibid., 23.

[29] Account from Painter (Pension Files) and Painter, Autobiography, 23. In his pension application, he indicated a wider plot: “I however soon had Serious thoughts of making my Escape with a number of Others which I affected within two or three Weeks by means of a bottle of Rum … I cannot recollect the names of any who made this attempt Except Capt. Elderkin my boat Commander.”

[30] Painter, Autobiography, 24. Elderkin swam to shore in New York, stayed hidden four days, but was captured and returned to the Good Hope.

[31] Robert Sheffield, a Long Island refugee in Connecticut, was captured in the spring of 1778 and put on a prison ship. He made his escape, arriving on June 19 back in Stonington, where he reported to Thomas Shaw: NDAR, Vol. 13, 192. Shaw wrote from Sheffield’s facts the florid account that was printed in Connecticut Gazette, July 10, 1778; also, NDAR, Vol. 13, 333. Similar facts were submitted by prisoners on the Judith to Rear Adm. Gambier; Gambier replied the next day, June 13: New Jersey Gazette, August 8, 1778. The Good Hope was hired June 16: Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714-1792, 353.

[32] Near 100° F temperatures at the battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778; 92° on August 5, 1778 in Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, Vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 292.

[33] New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, August 10, 1778.

[34] New London report: Maryland Journal, October 13, 1778; dates of release: Muster-Table of His Majesty’s Ship Ardent, ADM 36/ 7824, TNA, courtesy of Todd W. Braisted. In October: Daniel Jackson (Pension Files).

[35] Serve together: Rolls and Lists of Connecticut Men in the Revolution: 1775-1783 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1901), 243; Thomas Provost, Connecticut, No. S17028 (Pension Files); Elisha Elderkin, Connecticut, No. W17758 (Pension Files), Thomas Painter (Pension Files), Mischievous Puritan: Royal Gazette, July 31, 1779. The gravestone of Moses, Jr. says he was nineteen but he died two months before that birthday. www.findagrave.com/memorial/18137372/moses-mather.

[36] Infested: in Connecticut, Benjamin Tallmadge to Robert Howe, September 6, 1779, Litchfield (Connecticut) Historical Society, Tallmadge Collection, Series 1: Correspondence, Folder 8, Item 1; In NY: Royal Gazette (New York), September 9, 1782.

3 Comments

As part of the celebration of the Bicentennial the Town of Darien built a whale boat, complete with swivel gun. I believe it took part in races on the Sound. After not seeing it for many years it suddenly appeared on a trailer in front of the Darien Historical Society building, now renamed the Museum of Darien. It looked as if it has been very well taken care of.

Hi Chris. Yes, that 1976 Darien whaleboat spent the intervening years exhibited at the Norwalk Maritime Museum. When the museum decided to shift focus to become the Maritime Aquarium, the whaleboat was returned to Darien. I believe the Museum of Darien has restored it.

Though there were a number of Middlesex Parish men known to be involved in the whaleboat wars, the much larger harbors at Stamford and Norwalk were the real hubs for whaleboat action. The parish men most likely to be in whaleboats were the town’s Loyalists, who came back from Long Island to stage raids from Noroton Neck, Long Neck Point, Scott’s Cove, and Five Mile River.

Nicely researched and presented.