In researching one of the many projects I have in train, I ran across the Federal Pension Application file of Caleb Brewster. With all the public interest of late in him, Abraham Woodhull, Robert Townsend, and the Culper Spy Ring, I decided to take a more detailed look.

Brewster was first commissioned as the lowest-rated infantry officer, an ensign, in the 4th New York Regiment on November 1, 1776. Three months later, on January 1, 1777, he advanced to the rank of 1st lieutenant in the 2nd Continental Artillery. He was promoted to captain-lieutenant on June 23, 1780, was wounded on Long Island Sound in December 1782, and officially ended his military career on June 16, 1783.[1] Brewster “was placed on the pension list of the United States by a special act of Congress on the 11th Augt 1790.”[2]

Except for Brewster being an officer in the New York line, the information was really out of my wheelhouse, so I relayed it on to author and spycraft aficionado John Nagy, who I had recently met. I also told him of a reference in the file to one of Brewster’s men, Joshua Davis. John was intrigued, but he sadly passed away shortly after our meeting.

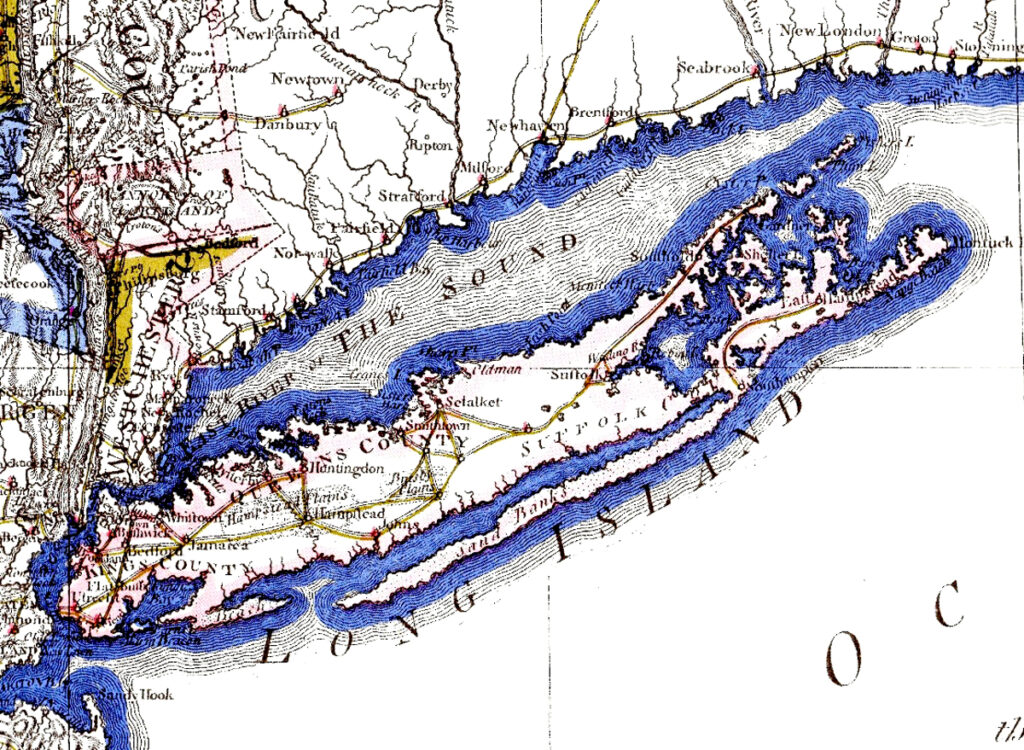

To honor John and to satisfy my own curiosity, I dug into the subject. I learned that the whaleboat men who ferried Brewster back and forth across Long Island Sound and attacked British shipping were actually skilled current and former soldiers organized into rotating crews, with more men attached to those crews as marines.[3] These enlisted men, mostly natives of Long Island and Connecticut, were transferred from different regiments as they were the most qualified for this particular service.

Following are brief accounts of the men I have been able to identify. Most served in Brewster’s boat, while others were in boats under Brewster’s overall command. Nearly all of them had been severely wounded or were in “reduced circumstances” that forced them to apply for financial assistance from the federal government in the form of a pension. It is these applications that form the nucleolus of their brief stories.

The Spy Boat Fight

Before getting to the men, here is background information on the legendary December 7, 1782’s “Spy Boat Fight.” Perceived to be much larger than what it actually was, this horrific hand-to-hand fight affected the lives of many of the participants and is reflected in their stories below. Due to the wounds he himself received, Brewster lost command of both his boat and the “Spy Boat” fleet.

In early December 1782, Brewster heard that Capt. Joseph Hoyt was in the Sound with three boats. Leaving three of his boats on the south-side of the Long Island to cover any escape, he gave chase with three others, including his own. Brewster eventually caught up to Hoyt. A couple of weeks later, Brewster told the story of the subsequent action to Maj. Gen. Henry Knox in gory detail:

We got close up with two of the Enemy, with two of my boats; (the other sailing [heavily];) they proved to be Capt. Hart & Lieut. Johnson; their other boat sailing faster or by being [far] ahead of them at the first of the Chase, escaped; being to windward, I bore down on the largest boat, and in passing Johnson received a full [fire] from him at the distance of about [eight Rods], which wounded me through the body, and one man in the Head, who is since dead, of the wound; I reserved my [fire] untill close alongside the boat. I designed the attack, (leaving Capt. Rider to contend with Johnson) with a view of having time only [its] charge again, and board him; but the briskness of the wind and the quick way of the boat prevented our loading before we Grappled. and having but three bayonets. we were obliged to make use of the butts of our Muskets, which decided the business in a short time; when we found but one man but what was either killed or wounded; five in boat were wounded (including the one who died a few days afterwards.) two of us with balls, the other with bayonets; the Enemy being much better fitted, had the advantage of us, Hart having three large wall pieces, and a compleat sett of Kings Muskets with long bayonets, I received Several blows from Hart with the Iron [Rammer] of a wall piece which fortunately did not prevent me doing my duty though it caused a pulsing of Blood; Johnson in the mean time surrendred to Capt. Rider without much resistance having had two killed by the [fire] of a Swivel Gun from Rider, Seven of the Enemy are buried two more lie at Norwalk badly wounded the rest am informd are prisoners at West point.[4]

Brewster recovered from his wounds enough to return to the “spy boats,” but was ultimately unable to continue. He wrote to President George Washington of his condition in 1792:

Early in the war, on the shore of Long Island from an exertion of bodily labor in carrying the boat I commanded into a place of safety & concealment, I received a dangerous & incurable rupture which has ever since been subject to the painful & inconvenient application of those modes of local support which are common in such cases—On the 7th of December 1782 while in the aforesaid service in a bloody engagement with two armed boats of the Enemy I received a wound by a ball thro. my breast—With this wound I languished & was confined two years & a half under distressing chirurgical operations & a most forlorn hope of cure. The nature of these wounds together with the impairing of my constitution by the long continuance of my confinement have rendered me incapable of any labour that requires a considerable exertion & have reduced me to the melancholy condition of an invalid for life.[5]

William Wheeler, a local teenager, recorded the happenings of the “Spy Boat Fight” in his journal:

Captain Caleb Brewster . . . with 3 whale-boats about midway of the Sound against Fairfield, met 3 of the enemy’s boats, when an engagement commenced. The boat that opposed Brewster had a small piece & was leeward; there was a fresh gale & Brewster reserving his fire till within 8 or 10 rods of Hoyt, poured in a broadside & then another & boarded; there was a large Irishman in the enemy’s boat, who walked several times fore and aft, brandishing his broad sword till Hasselton, a mighty fellow from the State of Massachusetts, snatched it from him & cut his throat from ear to ear; he died immediately.

Capt. Brewster being wounded was several times struck on the back with the steel rammer of a gun by Hoyt. On board of Hoyt’s boat all but one were killed or wounded. In Brewster’s boat 4 were wounded—one (Judson Sturges) mortally.

Another of our boats had a swivel (gun) which killed 2 men at one shot in another of the enemy’s boats & they immediately surrendered: the enemy’s third boat escaped.[6]

The Boys

Abner Beckwith: An outlier from those below who remembered the size of the whaleboat crews being larger, Beckwith explains that he served under Capt. Oliver Cornstock from April–July 1782 and that

There were seven men belonging to the boat. Captain Cornstock was regularly commissioned by [illeg.] Trumbull Governor of Connecticut. They were not employed the whole of the time in cruising the Sound but were held in constant readiness to go whenever they were ordered and whenever they returned to New London were required to make a regular report of their discoveries. The employment was peculiarly hazardous. Several of the men were wounded and Captain Cornstock very severely – He belonged with this boat more than three months – They captured a sloop during the time; and carried her to New London where she was condemned & sold.[7]

There could be several reasons why Beckwith remembered seven men on the crew. It may have simply been a smaller boat or that he did not count the marines, but what is clear is that serving on these boats was quite stressful and very dangerous.

Robert Brush: A Long Island native who lived in Connecticut during the war, he later settled in Pine Plains, Dutchess County, New York. Initially a Connecticut soldier, Brush fought in the 1777 battle of Ridgefield and was near Gen. David Wooster when he fell. While he was living in Norwalk, Connecticut:

he was in the habit of going with Lieutenant Caleb Brewster. . . to Long Island whenever Brewster called upon him—that he continued to go with him for the space of three or four years—that the number of these expeditions varied from one to three & four times a month—and in duration from two days to a week or more—That the object of said Brewster was to get intelligence from the British and it was their usual custom to start in the night and land on the Island at some place where they would not be discovered and lay concealed whilst Brewster went to some agent as he supposed whom he had on the Island & after obtaining the information he returned & they then embarked us secretly as possible for the mainland . . .

one time they were obliged to concealed on the ground for two weeks—the consequence of a snow storm—at other times he has been [out] one night & back the next—at other times they lay on the Island two or three days or more according as the information was obtained by Brewster more or less expeditiously or the danger of detection by the British required.[8]

Brush mentioned other incidents that occurred while he was rowing for Brewster:

at one time they had a skirmish with a boat crew of a Privateer on the Island after they had landed at another with a boats crew which they captured—At another time they were chased by a Privateer and escaped in consequence of being to the windward, the crew of their boat rowing further against the wind than the Privateer could beat—At another time they were chased by a Privateer when going into Stradford [Connecticut] harbor—the Privateer at that time being to the windward of them but they succeeded in getting over the bar before the Privateer could do them any damage although within reach of her guns—At another time he recollects that [they] were lying on the Island concealed a party of horse commanded by one Ismail Youngs a tory came in search of them and passed within fifty yards of their concealment but not discovering them.[9]

Brush then explained that:

Their crew commonly consisted of ten or twelve—recollects but few of them who went with them – but he recollects that one James Phillips—one Kinner—Dickenson—Veal—Van Horne—Foy—Soper and one Captain Conklin [most] generally went with them.[10]

After the war, Brewster, like he did for so many of his men, reported that “Robert Brush was a good and brave soldier” and “frequently volunteered his services on different occasions under me during the war on difficult and dangerous services, whilst I was engaged in secret service in Long Island Sound by order of General Washington.”[11]

Joshua Davis: In 1776, he first enlisted in Capt. Danial Griffing’s company of the 2nd New York regiment before joining Capt. Samual Sackett’s company of the new 4th New York regiment later that year. Davis explained that, after three years, he was merged into the 2nd New York regiment due to downsizing, and there he remained for the duration of the war. He was soon detached and “employed in what was called the whaleboat service,” but was still on the Continental establishment.[12]

A review of the muster rolls of Capt. Samual Sackett’s company confirms much of what Davis described. One roll, dated, January/February 1780 shows Davis, Cpl. David Dickerson, and Jonathan Kinner listed as being “on Command at Norwalk in the Whale Boats by order of his Excellency.”[13]

Davis briefly described that at this point he was

serving for a Special Service on board a certain whaleboat under Captain Caleb Brewster, who commanded a small fleet and had a commission to cruise Long Island Sound in the Continental Service & that I served on board said boat till the end of the war of the Revolution.[14]

Davis’s widow, Abigail, reported in greater detail that

her Husband had been taken from the Land Service into a Company under the command of Capt Caleb Brewster to go to & from Fairfield to Long Island for the purpose of watching and getting Information from the enemy which service was performed in a Whale Boat . . . as often as once a Week and continued in said Whaleboat service until the Peace . . .

She has heard her husband say was that he was selected to go in the whale boat with Captain Brewster because he was a Long Island man as also was Captain Brewster originally from Long Island and her husband being acquainted with the harbors there, caused him to be taken from the land service and put into this[15]

James Penfield “lived with his father in said Fairfield during the Revolution at a Place called Penfield’s tide Mills on Long Island Sound and said Brewster made it head quarters for his Boat at said Mills.”[16] He further explained that

Joshua Davis belonged to Capt. Caleb Brewster’s whale boat the latter part of the war and was one of his Principle men and cruised from said Town of Fairfield to and from Long Island to watch the enemy and was called a Spy Boat.[17]

Despite taking part in serious actions, like the “Spyboat Fight,” Davis seems to have come out of the war unscathed. He later did admit that all the physical abuse caught up to him in his later years. He stated “that in consequence of the severe service which I performed during the war I have a confirmed lameness in my left leg and am sometimes so lame in my back as to almost unable to rise from my chair.”[18]

Benjamin Dickerson: Another of Brewster’s own men to receive a bayonet wound in the “Spy Boat Fight,” he was a former 4th New Yorker who was part of the “advanced guard” at the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse. Dickerson explained that he had “belonged to the Company commanded by Captain Samuel Sacket in the regiment commanded by Colonel Henry Livingston (that he was detached with others therefrom into the boat-service on Long Island Sound when wounded, under Captain Caleb Brewster).”[19]

Davis explained that “Dickerson, himself & three others were detached from the army by the commander in chief, served under the command of Caleb Brewster in the Boat Service.” Over time, this service “had become more dangerous,” but they still “served with said Brewster until on or about the 7th day of December 1782, when said Dickerson was severely wounded by a bayonet in his right breast.”[20]

Backing up Dickenson’s memory, Brewster specifically named the five men reassigned from the Continental line when he explained that

he was requested to take the command of a boat to be employed under the immediate command of Gen. Washington in cruising in Long Island Sound, between the shore of said Island & the Connecticut Shore, for the purpose of obtaining information. & consent to take the command of a boat, for the purpose aforesaid, on condition that he might choose his men, which conditionwas [illeg.] to, & the deponent send to Gen Washington the names of David Dickerson, corporal, Zachariah Newkirk, Jonathan Kinner, Benjamin Dickerson, Joshua Davis who then all belonged to the New York line on the continental establishment, & said men were immediately sent to the deponent by General Washington.[21]

Brewster then explained that in the “Spy Boat Fight,” Dickerson was

dangerously wounded in the breast by a bayonet, which entered the right breast & pointed out under the shoulder blade, in a battle which was fought between the boat under the deponent’s command & a British Barge in Long Island Sound, in which battle 17 out of twenty five men engaged were either Killed or wounded, & said British Barge was captured; & that said Dickerson lingered for a long time in consequence of his wound, & did not in consequence of said wound again join the service, as the aforesaid battle, terminated the service of the deponent & his crew, in the boat aforesaid & he declares that said Dickerson was a brave & faithful soldier & on consequence of his would aforesaid was neither called upon nor able to perform further service.[22]

David Dickerson: As an early federal pension applicant and to meet the requirements of the law, he emphasized his term of service stating that he entered the army

on or about the month of December in the year 1776 in New Haven in the State of Connecticut with the Company commanded by Captain Samuel Sacket of the 4th regiment of the New York line commanded by Colonel Henry B. Livingston but was afterwards or [illeg.] to the Second New York regiment. That he continued to serve in said corps or in the service of the United States until the 7th day of June in the year 1783 when he was discharged from service in Newburgh in the State of New York – That he was in the Battles of Monmouth & the Taking of Burgoyne.[23]

Dickerson made no mention of his detached service in the whaleboats or his rank of corporal.

Jonathan Hazleton: Not all of the “Spy Boat” crews were from Connecticut or New York. Many had roots in other northeastern states. Hazleton was a native of New Hampshire, but after the war he lived in Rhode Island, Maine, and ultimately settled in Connecticut.[24]

Davis explained that Hazleton

had previously belonged to the Regiment under the command of Col. Seeley, in the New Hampshire line, on the continental establishment and do further testify that said Hazleton served under said Brewster in company with me for more than two years following the Spring of the year 1780 & was constantly employed in the Service of the United States & that he was ever considered a faithful soldier.[25]

Jonathan Kinner then confirmed that

Hazelton served under said Brewster for the term of two years at least and I understood . . . that he had been detached from the continental army by order of Gen. Washington.[26]

Hazleton’s transfer from the New Hampshire line to the whaleboats remains unclear. There are no known existing muster rolls from that line, but an account book that included members of Joseph Cilley’s regiment does survive. It shows that he enlisted for three years in the second company on February 12, 1777 and was discharged on January 25, 1780.[27]

Hezekiah Hyatt: A Norwalk, Connecticut resident for most of the war, he served in the local militia for various short-term duties and locations. Hyatt mostly made gabions or guarded the coast on land or in local boats on the edge of the sound. During this time, he was frequently detached from his company and

served under other Captains in the Boat Service. He served under Capt. John Rich, Daniel Jackson, Simeon Crossman, Ephraim Marion, Caleb Brewster, and Valentine Rider. Rich & Jackson belonged to Norwalk & the other Captains deponent thinks were from Long Island. These Boat Captains generally had about twelve men each under command & Rich & Jackson has special commission from Governor Trumbull to search the coast & guard the Sound.[28]

Jonathan Kinner: Enlisted in Capt. Samuel Sackett’s company of the 4th New York regiment in February 1777, he stayed until “the consolidation of the Regiments of the New York line.” He earned “a badge of Merit for six years faithful service.”[29]

Brewster explained that

Kinner who now resides in the Town of Weston, in the county aforesaid, was for several years under my command and that he was a brave and faithful soldier. . . & that he is now by reason of his reduced circumstances in life, in need of assistance from his Country for support.[30]

Kinner was a lifelong friend of Davis and explained that:

I have been well acquainted with Joshua Davis . . . from his youth to the present time as we were brought up within a few rods of each other, that we enlisted in the service of the United States, in Feb. 1777, in the Company of Samuel Sackett, in the regiment of Col. Livingston, in the New York Line, & that said Davis served in said Regiment & with me under Capt. Caleb Brewster to the termination of the revolution.[31]

The muster rolls of Sackett’s 4th New York company from August 1778 thru June 1780 indicate that many of these men including Davis, Benjamin Dickerson, Cpl. David Dickerson, Kinner, and a new name, Peter Denney, were “on Command at Norwalk in the Whale Boats by Order of his Excellency.” That phraseology does vary from one roll to another. Some of them appear to have gone in and out of the boat service.

Jared Lockwood: His service in 1776 has not been documented, but for the next three years he was an orderly sergeant in Ebenezer Steven’s company of the 2nd Continental Artillery. According to his widow, Elizabeth, “he fought in the Battles of Flatbush and Brooklyn, where the British Army advanced on New York in 1776. And at the Battle of White Plains in the same year. And that he fought at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778.”[32]

After his discharge, she and Lockwood were married, but

subsequent to their Marriage, her said Husband was engaged almost without interruption till the close of the War and the Proclamation of Peace, in various services—in cruising in the government armed boats in Long Island Sound and the East River, reconnoitering within the enemies lines, and in communicating with our friends within the enemies posts. That during those services he was at different times engaged under the following officers of various periods, with Captain Caleb Brewster, Captain Valentine Rider, Captain Jabez Fitch, and Lieutenant Andrew Mead, Captain Ebenezer Jones, and Lieutenant Samuel Heacock or Kickock. That said services were attended with great hazzards and fatiques, Many engagements occurred, and many prizes were taken and prisoners made. That her Hus ban was principally under the command of Captains Fitch and Jones. But this Declarant is unable to say under what enrollment her Husband acted.[33]

Most widows of war veterans were not the best on details of their husbands’ service. Her case is also light on specifics, but particularly good on names and places. She mentioned various captains, and suggested the overall size of the operation. She also noted that, in addition to the Long Island Sound, the “Spy Boats” also patrolled New York’s East River.

Joseph Lyon: Enlisting out of Danbury, Connecticut, he was in various short-term regiments for the bulk of the war. For most of his time, Lyon served as a teamster in and around the Hudson Highlands. During his last nine-month enlistment, he claimed to have served as one of the guards at the execution of Maj. John André at “Tappen Bay.”

He further explained that he saw action both before and during the “Spy Boat Fight:”

That he afterwards enlisted in the month of April 1781 at Fairfield in the State of Connecticut for the term of one year in a company commanded by Capt. Caleb Brewster of the Spy Boats on Long Island Sound. That he served in this company until the expiration of this year when he again volunteered his services without leaving the said company and continued with it until sometime in June 1782 when he received a furlough to go to Danbury when he would afterwards receive further orders from his Captain but was finally discharged from the army in December 1782. That during this enlistment he was in various engagements with the enemy, was at the taking of Fort Slongo, he was wounded by a bayonet at the taking of Hoyt of the British Whale Boat, the scar of which he now retains in his arm through which he was pinned to the boat in which he was engaged.[34]

Emery D. Potter, who appears to have not served with him, added to Lyon’s gruesome story when he related that Lyons

was with Capt. Brewster of the “Spy Boat Service,” on Long Island, when he was engaged in several sever fights, particularly at the taking of Fort Slongo: while in that action he was pinned to the boat which he had boarded, by the Bayonet of a British, the bayonet pierced his arm above the elbow, & while in that condition he discharged his musket with his other hand through the heart of his antagonist; I have often seen the sear on his arm.[35]

Sturges Ogden: An active militiaman for most of the war, Ogden also served as part of the seacoast guard in Fairfield, Connecticut. In addition,

he served in Embodied Corps maintained by public authority for the protection of the lives & property of the inhabitants against attacks of the British who were in posesion of Long Island, and that he always served as a private soldier on land & as an oarsman & marine in the boat under said Capt Brewster and that his services were constant and uninterrupted.[36]

According to Davis, in the spring of 1781 Ogden specifically “entered as a volunteer on board of the same boat in which I was under the same officers & continued in service with me the deponent on board of said boat till late in the fall of the same year.”[37] This should answer any questions of whether Ogden was a member of Brewster’s crew, but because of his short tour, he would not have been aboard for the “Spy Boat Fight.”

Benjamin Sturges: From “Fairfield town and County in the State of Connecticut,” Sturges served as a marine on board one of Brewster’s boats.[38] At some point during his service he received a bayonet wound, probably from grappling with the crew of an enemy boat on Long Island Sound. As result of this wound, he had “difficulty breathing, pain, and lameness of the side all which have arisen from the thrust of a bayonet through the body on the left side just above the hip” for the rest of his life.[39]

Hezekiah Sturges: As part of the Sea Coast Guard of Fairfield, Connecticut, he served several short tours of duty over a three-year period. “In Spring of the year 1781 he enlisted and served in a nine oared boat commanded by Abraham C. Woodhull” for about ten months in Brewster’s fleet cruising on Long Island Sound. Sturgesexplains “that in all his Land Service he served as a private soldier and in the Sea Service as an Oarsman and Marine.”[40]

Benjamin Sturges confirmed that Hezekiah Sturges: “volunteered & served with me the deponent the same year commencing when I did & continuing in service for the same term of time on board of a boat commanded as before stated.”[41]This means that they likely both served on Woodhull’s boat.

Conclusion

For decades the actions of Brewster’s whaleboat fleet were far better known than the secret work of the Culper Spy Ring, which was intentionally kept out of the public domain. These days, things appear to have reversed so that the whale-boaters and marines who secretly rowed across Long Island Sound and jousted with enemy vessels have been all but forgotten, but spy activities have been highlighted in various media outlets.

These oarsmen and marines are but a small sampling of all those who served in the “Spy Boat Service.” There are still many others that need to be identified and their stories examined. I hope I have sparked some interest among researchers to take up the challenge to find out more about these mariners who served so bravely and sacrificed so much.

[1]Entry for Caleb Brewster, Frances B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783, Reprint of the New, Revised, and Enlarged Edition of 1914, With Addenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932 (Baltimore MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1982), 119. A captain-lieutenant was essentially a lieutenant performing the duties of a captain. Elements of the 2nd Artillery were stationed all over the New York-Connecticut region since they were founded, so an unattached artillery officer would probably attract less attention than one from an infantry regiment stationed miles away. It is highly unlikely that, with all his “nocturnal activities,” Brewster ever served with the artillery in the field.

[2]Brewster to J.C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, March 24, 1820, S.28367, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900, Record Group 15, National Archives Building, Washington, DC (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804, Roll 0332) (Pensions).

[3]Marines are soldiers that serve on land and afloat. The marines who served on the “spy boats” were not part of the Continental Marines.

[4]Brewster to Henry Knox, December 21, 1782, Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC02437.01755. Transcript at www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc0243701755, accessed August 19, 2023. Some words in the transcript are in square-brackets. presumably to indicate they are the best guess of the transcriber. Captain Rider is likely Capt. Valentine Rider referenced by Elizabeth Lockwood later in this article.

[5]Brewster to George Washington, March 15, 1792, Founders Online, National Archives,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-10-02-0062, Accessed August 19, 2023.

[6]William Wheeler, The Journal of William Wheeler, reprinted in Cornelia Penfield Lathrop, Black Rock, Seaport of Old Fairfield, Connecticut, 1644-1870 (New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1930), 34-35.

[7]Deposition of Abner Beckwith, August 9, 1832, Pensions (S.12158, Roll 197).

[8]Deposition of Robert Brush, October 13, 1832,Pensions (S.23555,Roll 387).

[9]Deposition of Robert Brush, November 9, 1835, ibid.

[11]Deposition of Caleb Brewster, January 15, 1827, Pensions (S.23555,Roll 387).

[12]Deposition of Joshua Davis, June 14, 1820, Pensions (S.14049, Roll 1839).

[13]A Muster Roll of Captain Saml Sackets [Company] in the 4th New York Regt in the Service of the United States, January & February 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Records Group 93, Roll 71, Folder 67.

[14]Deposition of Joshua Davis, July 28, 1832, Pensions (S.14049, Roll 1839).

[15]Deposition of Abigail Davis, October 1, 1836, Pensions (S.14049, Roll 1839).

[16]Deposition of James Penfield, November 16, 1836, Pensions (S.14049, Roll 1839).

[18]Deposition of Joshua Davis, June 14, 1820, Pensions (S.14049, Roll 1839).

[19]Deposition of Benjamin Dickerson, October 6, 1827, Pensions (S.27691, Roll 0810).

[20]Deposition of Joshua Davis, April 26, 1820, ibid.

[21]Deposition of Caleb Brewster, April 25, 1821, ibid.

[23]Deposition of David Dickerson, May 6, 1818, Pensions (S.44145, Roll 0810).

[24]Deposition of Jonathan Hazleton, November 7, 1831, Pensions (W.23194, Roll 1239).

[25]Deposition of Joshua Davis, August 7, 1818, ibid. Col. Seeley is probably Col. Joseph Cilley who commanded the 1st New Hampshire regiment from April 2, 1777 to January 1, 1781. Enry for the 1st New Hampshire Regiment of 1777, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units: Battalions, Regiments and Independent Corps, Fred Anderson Berg (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972), 79.

[26]Deposition of Jonathan Kinner, August 7, 1818, ibid.

[27]Entry for Jonathan Hazleton, US, New Hampshire, Revolutionary War Records, 1675-1835, Cilley and Reid Regiments (2nd capture), 1776-1779, Regiments, 109, fold3.com/image/713075618, accessed August 20, 2023.

[28]Deposition of Hezekiah Hyatt, February 19, 1836, Pensions (R.5461, Roll 1386).

[29]Deposition of Jonathan Kinner, April 4, 1818, Pensions (S.37131, Roll 1493).

[30]Deposition of Caleb Brewster, April 4, 1818, ibid.

[31]Deposition of Jonathan Kinner for Joshua Davis, April 4, 1818, Pensions (W.17698, Roll 760).

[32]Deposition of Elizabeth Lockwood, December 7, 1836, Pensions (W.16639, Roll 1577). Orderly sergeants handled the administrative duties for the company and its commander. They would later be called first sergeants, a rank that still exists today.

[34]Deposition of Joseph Lyon, October 16, 1832, Pensions (S.23306,Roll 1608). The Battle of Fort Slongo occurred on October 3, 1781. Benjamin Tallmadge, organizer of the Culper Spy Ring, was a commissioned officer in the 2nd Light Dragoons, and, after being ferried with his men to Long Island via whaleboats, commanded the attack on the fort. Sgt. Elijah Churchill, of the 2nd Light Dragoons, was awarded the Badge of Military Merit, the forerunner of the modern Purple Heart decoration, for his actions in this and other battles in the region.

[35]Letter from Emery D. Potter supporting Joseph Lyon’s pension claim, December 18, 1835, Pensions (S.23306,Roll 1608).

[36]Deposition of Sturges Ogden, May 23, 1833, Pensions (S.14049,Roll 1839).

[37]Joshua Davis Deposition, July 28, 1832, ibid.

[38]Deposition of Benjamin Sturges, November 1, 1819, Pensions (W.25073, Roll 2319).

[39]Physician’s & Surgeon’s Affidavit, January 17, 1826, ibid.

[40]Deposition of Hezekiah Sturges,April 23, 1833, Pensions (S.14601,Roll 2319). This was not the same Abraham Woodhull who was a member of the Culper Spy Ring.

[41]Deposition of Benjamin Sturges, July 27, 1832, Pensions (S.14601,Roll 2319).

2 Comments

Phil:

Another outstanding job! Really appreciate your attention to detail and lively writing. Brings history back to life. Keep ’em coming!

Joe

Caleb Brewster would return to active service in the Revenue Cutter Service and would command the revenue cutter “Alert” during the War of 1812 and act as eyes of the Navy on the Long Island Sound.