On the blazing afternoon of June 17, 1775, two forces met on the Charlestown peninsula just outside Boston, Massachusetts.

An unstoppable force of red-clad British troops swept ashore and broke upon the immovable walls of the provincial fortifications atop Breed’s Hill, crashing across the Charlestown peninsula like a blood-red wave. Flood waters of British soldiery climbed higher and higher up the slopes of the hill, rising until repulsed by heavy fire from the provincial muskets that bristled from the walls of the earthen fort, only to surge again.

Provincial soldiers defended the redoubt atop Breed’s Hill, their simple homemade clothing streaked with dirt from digging the walls of the earthen fort that surrounded and sheltered them. New England soil shoveled and shaped overnight for the protection of New England men.

Blood met earth, hundreds of times that afternoon, as men in blood-red coats and men in dirt-dusted homespun, fell to the ground, bone shattered by musket ball, and flesh torn by bayonet.

The smoke from burning Charlestown has long since dissipated. The crack and blaze of musket fire has long since faded. The walls of the redoubt have long since returned to the earth—as have the soldiers who scaled and defended them.

All that remains of the Battle of Bunker Hill are the words of the men who were there.

Cpl. Peter Brown

We worked there undiscovered till about five in the morning, then we saw our danger, being against ships of the line, and all Boston fortified against us.[1]

Twenty-two-year-old Peter Brown numbered among the approximately 1,200 provincial soldiers ordered to march from Cambridge and entrench on a hill in Charlestown on the night of June 16, 1775. The troops dug through the darkness, throwing up a fortification on Breed’s Hill that would shock British senses when daylight broke on June 17.

Isaac Glynney

We did as before—reserved our fire until they came within about six or seven rods, then we showed them yankee play and drove them back again. But soon they renewed the attack and came again. But we, being destitute of ammunition, made use of ammunition called cobble stones.[2]

Isaac Glynney was not yet fourteen years old when he served with the provincial forces at the Battle of Bunker Hill in the stead of his sick father.[3] The British twice attempted to breach the walls of the redoubt but were driven back each time by heavy provincial fire. Finally, as provincial ammunition ran low and fire slackened, the British succeeded in breaching the redoubt in a final surge. Provincial troops wielded their muskets as clubs while others hurled stones as their only defense against British bayonets.

Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne

And now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived: if we look to the height, Howe’s corps ascending the hill in the face of entrenchments . . . a large and a noble town in one great blaze . . . the roar of cannon, mortars, and musketry . . . to fill the ear; the storm of the redoubts . . . to fill the eye; and the reflection that perhaps a defeat was a final loss to the British empire in America, to fill the mind.[4]

British General John Burgoyne watched the battle from his position at the Copp’s Hill battery in the north end of Boston, just across the Charles River from the Charlestown peninsula. With dramatic flair, he captured the overwhelming sensory experience of the battle.

Lt. Francis, Lord Rawdon

They rose up and poured in so heavy a fire upon us that the oldest officers say they never saw a sharper action. They kept up the fire till we were within ten yards of them; nay, they even knocked down my captain, close by side me, after we got into the ditch of the entrenchment.[5]

Francis, Lord Rawdon participated in the battle as a lieutenant under Capt. George Harris in the 5th Regiment of Foot grenadier company. Both Lord Rawdon and Captain Harris ascended Breed’s Hill in the face of heavy provincial fire in the attempt to storm the redoubt.

Captain Harris was shot in the head and fell to the ground. Lord Rawdon, believing Captain Harris to be dead, attempted to move him to prevent his body from being trampled by surging troops. But upon moving the captain, Rawdon realized that Harris was still alive and ordered four soldiers to carry Harris off the field.

Capt. George Harris

They still every day peep at my brain, which, all things considered, is not an unlucky circumstance, as it may convince you and the rest of the world that I have such a thing.[6]

Captain Harris was ferried back to Boston where he underwent emergency cranial surgery. Surgeons trepanned his skull to relieve the pressure of the blood that was building inside his head due to his wound. Trephination involved boring a hole in the skull to relieve the pressure, and in Captain Harris’s case, removing bits of “matter” from inside his head which were causing excruciating pain.

During the procedure, physicians held a mirror up to the back of Captain Harris’s head which granted him the dubious opportunity to view his own brain.

Defying all odds, Captain Harris recovered quickly from both the wound and the trephination. A mere five weeks later, in a letter to his cousin, he demonstrated that not only had his body and brain survived the Battle of Bunker Hill intact, but so did his sense of humor.

Lt. John Waller, British Marines

I cannot pretend to describe the Horror of the Scene within the Redoubt, when we enter’d it, ‘twas streaming with Blood & strew’d with dead & dying Men, the Soldiers stabbing some and dashing out the Brains of others was a sight too dreadful for me to dwell any longer on.[7]

Lt. John Waller of the Marines was among the British troops who stormed the provincial redoubt, dropping over the earthen walls of the fort, and “driving bayonets into all whom opposed them.”[8] A final desperate struggled ensued between the defending provincial stalwarts and the furious British troops.

Cpl. Amos Farnsworth

I did not leave the entrenchment until the enemy got in. I then retreated ten or fifteen rods. Then I received a wound in my right arm, the ball going through a little below my elbow, breaking the little shell bone. Another ball struck my back, taking a piece of skin about as big as a Penny. But I got to Cambridge that night.[9]

As hand-to-hand combat broke out inside the dirt walls of the redoubt, Col. William Prescott, ordered a retreat. Provincial troops like Cpl. Amos Farnsworth of Groton, Massachusetts, fought their way out of the redoubt and retreated toward Bunker Hill and Charlestown Neck, under the cover of other provincial troops who had been positioned elsewhere on the Charlestown peninsula, at the rail fence.

Lt. Samuel Blachley Webb

But alas how Dismal was the Sight to see the Beautiful & Valuable town of Charlestown all in Flames—and now behold it a heap of Ruins—with nothing Standing but a heap of Chimneys,—which by the by remains an Everlasting Monument of British Cruelty and Barbarity.[10]

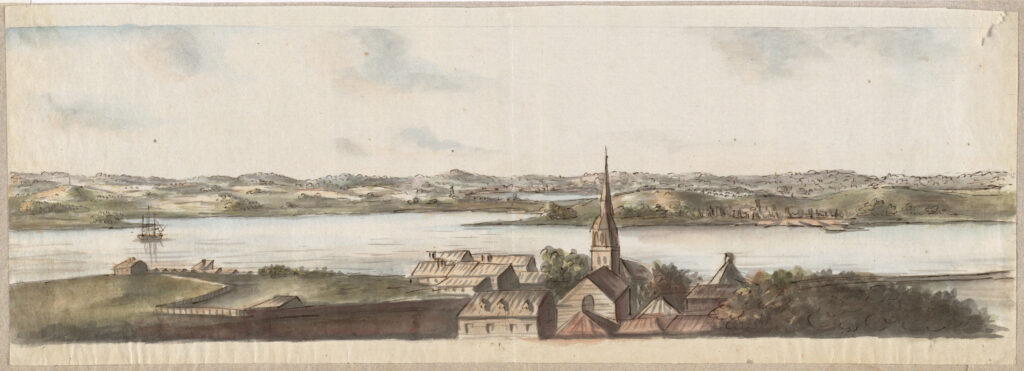

Lieutenant Webb served in the company of Capt. John Chester of Connecticut which was ordered to march to Charlestown that afternoon. At the outset of the battle, provincial marksmen had been positioned in the buildings of Charlestown village to harass the British left as it staged its attack on the redoubt. In retaliation, the British reduced the village to a heap of ashes—lobbing exploding shells into the town from the Copp’s Hill Battery. Nothing remained of Charlestown village except old stone foundations and the skeletal outlines of chimneys.

General Sir William Howe

The General’s returns will give you the particulars of what I call this unhappy day—I freely confess to you, when I look to the consequences of it, in the loss of so many brave Officers, I do it with horror—The success is too dearly bought.[11]

General Sir William Howe served as the commanding British officer on the ground in Charlestown during the Battle of Bunker Hill. The battle raged not just on Breed’s Hill but across the entire Charlestown peninsula—from Charlestown village on the southwestern tip, to the shore of the Mystic River, over and across both Breed’s and Bunker Hills, to Charlestown Neck, that narrow strip of land that connected Charlestown to the mainland. The British drove the Americans across that neck and out of Charlestown within a couple short hours. However, the provincials extracted a heavy price for British possession of the peninsula. Comprising a combined force of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire men, the provincials inflicted over twice as many casualties as the British. Over 1,000 British soldiers were killed, wounded or captured, compared to about 450 provincial troops.

The British encamped in Charlestown on the night of June 17 and fortified Bunker Hill. But they launched no incursions into the Massachusetts countryside for the remainder of the Siege of Boston.

The British evacuated Boston exactly nine months later, on March 17, 1776.

[1]Peter Brown to Sarah Brown, June 25, 1775, in Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=725&pid=2.Note that in some instances, the author has modernized the eighteenth century capitalization, punctuation and spelling to render the quote more easily understandable, without changing the overall meaning. The original quotation by Peter Brown is, “we work’d there undiscoverd till about five in the Morning, then we saw our danger, being against Ships of the Line, and all Boston fortified against Us.”

[2]Isaac Glynney, “Diary of Isaac Glynney”, digital reproduction of original manuscript, Harlan Crow Library, Dallas, TX. The original quote by Isaac Glynney is, “We Did as before Reservd our fire till they Came within About six or seven Rods then we Shoed. them yankey Play & Drove them Back again But soon they Renud. the attact & Came agin But we Being Destetute of aminition we made use aminition calld. cabel stones.”

[3]Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War(Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Company, 1899), 499. Isaac Glynney’s father was John Glenne/Glynney, who enlisted in Captain Bancroft’s company, Colonel Bridge’s regiment.

[4]John Burgoyne to Lord Stanley, June 25, 1775, American Archives, ed. Peter Force (Washington, D.C., 1843), Ser. 4, 2:1095, digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A87089.

[5]Francis, Lord Rawdon to Francis, tenth Earl of Huntingdon, June 20, 1775 in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants, eds. Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 130-131.

[6]George Harris to cousin, in S.R. Lushington, The Life and Services of General Lord Harris During His Campaigns in America the West Indies and India(London: John W. Parker, 1840), 57.

[7]John Waller to unidentified recipient, June 21, 1775 in Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=726.

[8]John Waller to his brother, June 22, 1775, in Samuel Adams Drake, Bunker Hill: The Story Told in Letters from the Battle Field by British Officers Engaged(Boston: Nichols and Hall, 1875), 28.

[9]Amos Farnsworth, Diary, June 17, 1775, in Three Military Diaries Kept by Groton Soldiers in Different Wars, ed.Samuel A. Green (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1901), 90. Amos Farnsworth’s original diary entry is, “I Did not leave the Intrenchment until the Enemy got in I then Retreated ten or Fifteen rods, then I received a wound in my right arm the bawl gowing through a little below my elbox breaking the little shel bone Another bawl struck my back taking a piece of Skin about as big as a Penny but I got to Cambridge that night.”

[10]Samuel Blachley Webb to Joseph Webb, June 19, 1775, in Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb, Volume 1 (Lancaster: Wickersham Press, 1893), 65-66.

[11]William Howe to unidentified recipient, June 22 and 24, 1775, in The Correspondence of King George the Third from 1760 to December 1783, ed. Hon. Sir John Fortescue, Volume 3 (London: MacMillian & Co., 1928), 223.

Recent Articles

Reluctant Ally: The Dutch Republic and the American Revolution

An Enemy at the Gates: The Tragedy of Abraham Carlile

Siege: The Canadian Campaign in the American Revolution, 1775-1776

Recent Comments

"An Enemy at the..."

Bob: Great Article! I never heard of Abraham Carlile and his fate....

"The Complicated History of..."

This is clearly the best thing that I have Read on any...

"The Sieges of Fort..."

Peter, thank you for your comments. I found no primary sources describing...