Solomon Tift was long believed to be one of the last surviving veterans of the Battle of Groton Heights in Groton, Connecticut. Daniel Eldridge was also supposedly there with Tift heroically defending Fort Griswold. But neither man was there. In fact, on September 6, 1781, while the battle raged, Tift and Eldridge were not defending Fort Griswold. Rather, they were 200 miles away in New York, sitting on the Jersey prison ship.

Solomon Tift was born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island, on May 28, 1758, and resided there at the outbreak of the war. In March 1777, at eighteen years old, Tift enlisted in an independent militia company, the Kingston Reds, that had been raised in his hometown by John Gardner, who became the company’s first captain. Later that spring, the Kingston Reds joined two other independent companies, the Kentish Guards and the Pawtuxet Rangers, and formed a regiment led by the newly promoted Col. John Gardner. The terms of enlistment, according to Tift, “were such that all the members of the companies were to hold themselves in readiness for service at any time at a minutes warning, but were not to be marched out of the State nor to be subject to any draft.”[1]

The company did three one-month tours guarding various points along the coastline of Rhode Island, which was under constant threat by the British garrison in Newport.

The first tour of the Kingston Reds was at Point Judith in southern Rhode Island in March 1777. Point Judith overlooked the Atlantic Ocean as well as the approaches to Newport. The company was stationed there for one month to, according to Tift, “guard the inhabitants against the depredations of Capt. [James] Wallace,” commander of the British warship Roseand later Experiment, who had terrorized the coast in late 1776. Tift’s second tour with the Kingston Reds was at Tower Hill in Boston Neck, about seven miles north of Point Judith, in the early fall of 1777. They were stationed there for a month “in consequence of the frequent landings and depredations from the enemy” coming out of Newport. His third and final tour with the Kingston Reds was in November 1777. This time they were stationed at South Ferry, ten miles north of Point Judith, where they again performed guard duty. It was at that time that Tift came close to seeing action for the first time.[2]

On November 6, the twenty-eight-gun British frigate Syren was convoying a transport ship and a schooner from Newport to Shelter Island in Long Island Sound to collect firewood, but due to poor visibility got stuck and ran aground off Point Judith. The British were forced to abandon the Syren and used the schooner to take off her crew. They were discovered the following morning by militia stationed there. Armed with “some field-pieces,” the militia fired on the schooner as it was attempting to evacuate the crew of the Syren. A shot struck the schooner and “cut her main halliards” and forced her to surrender. The transport ship got away. Even though Tift did not participate in the action, it caused enough excitement at the time that he felt to include it in his post-war pension application.[3]

Following Tift’s third term of service, he returned home. The following summer, he enlisted again on June 12, 1778, into Capt. Benjamin West’s Company in Col. John Topham’s Regiment. He was a late enlistee, as the regiment had already been in service since the previous March. Despite this, this term of service would be Tift’s longest, nine months.

Tift marched with Topham’s Regiment from Little Rest (present-day Kingston) to Providence, where they joined the army under Maj. Gen. John Sullivan that was about to besiege Newport. They were assigned to the brigade of Brig. Gen. Ezekiel Cornell in the first division. On August 9, they moved to Howland’s Ferry where they crossed over to Rhode Island, where according to Tift, “they moved neared to Newport and besieged that place with the intention of making an attack.”

Twenty days later, Tift stated “he was in the battle of the 29th August [the Battle of Rhode Island] wherein the American army compelled the enemy to retreat.” Topham’s Regiment was involved in the defense of Anthony’s Hill, where they helped repulse assaults on the hill by both British and Hessian forces. By the end of the day, the British and Hessians gave up their attack and instead held their positions. The following day, Tift recollected the American army gave up the siege and “abandoned the island without loss.”[4]

Following the Battle of Rhode Island, Tift was detached from West’s Company and Topham’s Regiment, where according to Tift, he spent a “considerable portion of the term in a guard boat around the north end of [Rhode] Island thence down to Howlands Ferry and as high up as Bristol.” Tift returned to Tiverton where he was discharged in February 1779.[5]

This latter term may have convinced Tift to make his next decision, to enter the privateer service.

Unfortunately, this fifth tour of service is completely missing from Tift’s post-war pension application, a somewhat common occurrence for veterans if they did not have any witnesses to back up their services. The pension bureau could deny assistance if the veteran could not sufficiently back up their services during a particular period, so veterans sometimes focused on periods of service which could be backed up by a deposition of someone who served with them.

Sometime in 1779, possibly after he was discharged from Topham’s Regiment, Tift left South Kingstown and moved to Groton, Connecticut. There he married Eunice Burrows in early December.

Tift’s next documented tour of service was in early August 1781, where he enlisted aboard the privateer brig Favorite, under Capt. Jonathan Buddington, and sailed out of New London harbor a short time later. Also aboard the Favorite was Daniel Eldridge, of Groton Bank, who was only seven months younger than Tift. Unfortunately, not much else is known about Eldridge, though by this time he may have been a veteran privateersman.[6]

Only a few days into the planned two-month cruise, the Favoriteengaged and captured the British letter of marque brig Dan. After the surrender of the Dan, Tift and Eldridge were ordered to be a members of the “prize crew” of a captured vessel and were ordered by Captain Buddington to sail it back to New London harbor where it could be brought before the admiralty court, condemned, sold, and the prize money dispersed amongst the crew of the Favorite.[7]

Unfortunately, neither the Dan, Tift nor Eldridge made it back to New London. Enroute, the Dan was recaptured by the British frigate Solebay. Tift, Eldridge, and the other members of the prize crew were transported by the Solebay to New York City where they were placed aboard the Jersey prison hulk. Both Tift and Eldridge were held as prisoners until December, thus, entirely missing the action at Groton Heights on September 6, 1781.[8]

Both Tift and Eldridge appear to have returned to New London harbor, with as many as 130 naval prisoners, on December 3. Tift returned home to his wife and daughter in Groton. He and his wife eventually had twelve more children, and he lived until 1850, long enough to collect a pension from the Federal Government for his service and to have his photograph taken.[9]

Eldridge did not fare as well. He returned home “sick, starved, and nearly dead.” When he was taken in by family, they were “careful feeding him to restore him to health, but in a moment when they were caught off guard, he reached [for] a bowl of cider and [drank the entire bowl], though the physician’s orders were a spoonful at a time. The meal was too much for his exhausted system and died almost at once” on January 1, 1782.[10]

So how did Tift and Eldridge end up being listed as members of the garrison at Fort Griswold when they were not? Long story, short, we do not know.

There is one plausible explanation: it was accidental. Both men were captured within days of the attack on Fort Griswold. Both were exchanged and returned home about the same time as the prisoners taken at New London and Groton. And since no one looked any further into the two cases, the two men became “prisoners taken at Fort Griswold” and this became accepted fact over time.

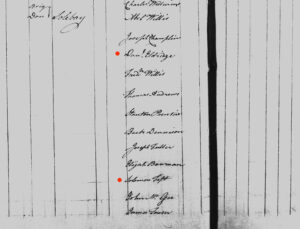

Since then both men continue to appear on lists of defenders of Fort Griswold both in publication and at the battlefield itself. Both names are listed on the bronze plaque on the Memorial Gates at the entrance of Fort Griswold Battlefield State Park, dedicated at the 130th Anniversary of the battle in 1911.

Looking into each man’s case a little further, we learn some interesting facts. Tift’s association with Fort Griswold began weeks after the battle when his name mysteriously appeared on a list of men who were killed at the fort published by the Connecticut Gazette on September 21, 1781. Since he was not in fact killed there, it was probably supposed by family that he was there, but he just was not killed there, and instead taken prisoner. When he returned home, it was assumed he had been in the fort.[11]

Tift in his pension application never mentioned participation at Fort Griswold. However, the application does include a note from a descendant who was searching for information about Tift. All this descendant knew about him was his supposed involvement at Fort Griswold and his time on the Jersey. While we do know Tift was on the Jersey, a vessel that held naval prisoners, we also know that no prisoner taken at either New London or Fort Griswold on September 6, 1781, was ever on the Jersey. All off those prisoners were taken on the land and therefore kept in Livingston’s Sugar House in New York.[12]

Eldridge’s connection to Fort Griswold appears to have been made around the same time as Tift. The mistake involved a second man from Groton with a similar name who did serve at Fort Griswold the day of the battle. This was a Sgt. Daniel Eldridge, of the 3rd “Groton” Company, who resided in the eastern part of the town, closer to Stonington. Sergeant Eldridge was wounded, captured, and paroled by the British before they departed Groton. Despite this, the name Eldridge appears twice on a list of American casualties sustained at New London and Fort Griswold—Sergeant Eldridge, under “wounded,” and Daniel Eldridge under “prisoners” taken to New York. Also on the latter list was Solomon Tift.[13]

There is no doubt that Solomon Tift and Daniel Eldridge both deserve to be honored for their services to their country during the Revolutionary War. But if we were able to talk to either man today, they would perhaps be very confused. They would probably ask us, why are we being remembered for being at the Battle of Groton Heights? We were never there.

[1]Solomon Tift Pension Application (S.14703), Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

[3]Frederick Mackenzie, The Diary of Frederick Mackenzie (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930), 1:210; Virginia Gazette, December 19, 1777; Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2011), 44. According to Mackenzie, the schooner was from the “wood fleet” and the transport was carrying 100 soldiers from the 54th Regiment of Foot under Maj. Edmund Eyre. A sloop arrived and the transport ship carrying the British regulars managed to get away. Eyre later led the British soldiers who attacked Fort Griswold. The militia belonged to the 2nd Regiment of King’s County Militia and Robinson’s Regiment of Massachusetts Militia.

[4]Solomon Tift Pension Application (S.14703), National Archives.

[6]Samuel Edgcomb Pension Application (S.20743), National Archives. Not much is known about Eldridge’s military service prior to 1781. Edgcomb listed a Daniel Eldridge from Groton as a “sailing master,” in the privateer service meaning Eldridge was responsible, at least at one time, for the sailing and navigation of a naval vessel. Daniel’s brother was Charles Eldridge, a merchant from Groton Bank; it may also be plausible Daniel worked for brother as well.

[7]Connecticut Gazette, August 10, 1781, September 27, 1781; Royal Gazette (New York), August 28, 1781; Ship’s Muster Book, HMS Jersey, ADM 36/9579, British National Archives. Also aboard the Favoritewas Daniel Shapley, the only son of Capt. Adam Shapley who was mortally wounded at Fort Griswold.

[8]Ship’s Muster Book, HMS Jersey, ADM 36/9579, British National Archives.

[9]Connecticut Gazette, January 4, 1782.

[10]Connecticut Gazette, January 4, 1782; Carolyn E. Smith and Helen Vergason. September 6, 1781: North Groton’s Story (Ledyard, CT: Ledyard Historical Society, 2000), 120; William W. Harris, The Battle of Groton Heights: A Collection of Narratives, Official Reports, Records, Etc. of the Storming of Fort Griswold, The Massacre of Its Garrison, and the Burning of New London By British Troops Under the Command of Brig.-Gen. Benedict Arnold, On the Sixth of September, 1781ed. Charles Allyn (New London, CT: Charles Allyn, 1882), 243-244. There are conflicting dates of death for Eldridge. One date is December 11, 1781, a second, listed on his gravestone, is November 18, 1781, and yet another published in the Gazetteas January 1, 1782.

[11]Connecticut Gazette, September 21, 1781.

[12]Solomon Tift Pension Application (S.14703), National Archives; Matthew E. Reardon, The Traitor’s Homecoming: Benedict Arnold’s Raid on New London, Connecticut, September 4-13, 1781 (El Dorado, CA: Savas Beatie, 2024)

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...