Substantial numbers of British and Hessian troops needed to be housed in New York City and across Long Island during the years of the British occupation from 1776 to 1783. An American report to General Washington in January 1779 estimated the number of British and allied troops stationed on Long Island at approximately 3,380 exclusive of Delancey’s Brigade and calvary.[1]

Previous to the outbreak of the Revolution the English Parliament enacted the Quartering Act, requiring that American colonial governments provide accommodations, supplies and transportation to British soldiers in the colonies. Soldiers quartered at inns, taverns, churches, barns and farm outbuildings, but the Quartering Act prohibited British soldiers from entering private houses.[2] With the start of the Revolutionary War, more extensive quartering became a necessity for the British army, and the rules of the Act were no longer in effect.

Quartering, also known as billeting, was so named from the “billet” or ticket that the soldiers showed to the master of a private house as their warrant to occupy a part of it. The colonists were in return to be issued payment for the partial use of their houses. Billeting with citizens greatly challenged the notions of privacy within the home. There was daily personal interaction between the local population and military troops.[3] With the amount of soldiers quartered in private homes in the New York region, the war would have touched many people’s lives in a very personal way.

One of the most descriptive explanations of billeting on Long Island is recorded in the writings of historian Henry Onderdonk Jr.:

During the summer British troops were off island on active service, or if a few remained here they abode under tents; but in winter they were hutted on the sunny side of a hill, or else distributed in farmer’s houses. A British officer accompanied by a justice of the peace or some prominent loyalist as a guide, rode around the country, and from actual inspection decided how many soldiers each house could receive, and this number was chalked on the door.

The soldiers were quartered in the kitchen, and the inner door nailed up so the soldiers could not intrude on the household.[4]

He continues,

Each Family was allowed one fire-place, and the officers fixed the number of soldiers to be billeted in each house, which was usually from 10 to 20. They had three tiers of hammocks one above the other, ranged round the room, and made of boards stripped from some fence or outbuilding.[5]

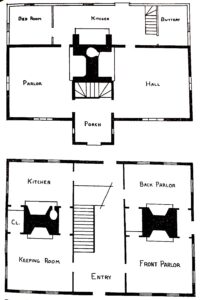

and eighteenth-century central passage house. From Abbott L.

Cummings , ed. Rural Household Inventories.

What Onderdonk called “hammocks” were actually wooden berths. The typical kitchen space in the colonial farmhouse had its own entrance and because of this the room could be easily closed off from the rest of the house.

Non-commissioned officers would either be quartered with billeted soldiers or housed close enough to their men to check in on them. The below order describes billeting in Newtown, Long Island in December 1777:

Particular Care is to taken in the Arrangement of Billeting that the Non Commissioned Officers shall be properly disposed of, and such Billets as cannot have a Non Commissioned Officer Immediately therein the Men so disposed of are to be Visited by the Adjacent Non Commissioned Officers at such times of the Day and Night as they shall think most proper[6]

Billeted soldiers also had restrictions on how far away from their quarters they could be and also had a curfew.

No Soldier is to go more than half a Mile beyond the district of the Quar. of the Batt. without a pass from the Commanding Officer. Neither is any Soldier to be out of his respective Billet after the Hour of Eight O’clock at Night under pain of being punished for the same & shall any Non Commissioned Officer winke or connive at a breach of this or any other Order, they shall be tried for contempt of the same & punished at the discretion of a Court Martial[7]

Contrasting with the rank and file soldiery, British and allied officers usually quartered in many of the better rooms of the house. Sometimes they occupied more than one room. Officers in many cases required accommodation for a servant and sometimes for a horse. An order from a British barrack-master in Jamaica, Long Island to a local homeowner states,

Finding that your house will justly admit of receiving a Billet, you are therefore Directed To Provide Mr Cutler. Forrage Master to the Hessian Chassure Corps, with one good Room. The use of the Kitchen and place for his servant To sleep in.[8]

A similar experience of billeting is told in a diary by Elizabeth Drinker of Philadelphia in 1778 when the British occupied that city. Although not a Long Island story, it records a similar day to day experience of billeting an officer in a private home. She states,

Cramond here this morning, we have at last agreed on his coming to take up his aboud with us, I hope it will be no great inconvenience, tho I have many fears, he came again in the Afternoon with a servant to look at the Stable, stay’d Tea.[9]

A few weeks later the officer had adjusted his accommodations within the house,

This Morning our officer mov’d his lodgings from the bleu Chamber to the little front parlor, so that he has the two front Parlors, a Chamber up two pair of stairs for his baggage, and the Stable wholly to himself, besides the use of the Kitchen, his Camp Bed is put up.[10]

After some time her diary records the hardship of sharing her home with the officer and his social schedule. This appears to be a common experience of housing officers in private homes.

it is now between 11 and 12 o’clock, and our Officer has company at Supper with him: the late hours he keeps is the greatest inconvenience we have as yet suffer’d by having him in the House . . . . our major had 8 or 10 to dine with him, they broke up in good time, but he’s gone off with them and when he’l return I know not, I gave him some hints 2 or 3 days ago, and he has behav’d better since[11]

The quartering of officers appears to have also had trade-offs with some positive benefits to the household. Historian James Riker wrote that British officers provided security against marauders as the officers were usually attended by one or more soldiers and had a sentry which paraded at the front door. It also mentions that officers paid well for their board, with a customary twenty shillings per week. Food acquired by officers also helped supply the household. Payments were made in gold and silver.[12]

In certain cases there was abuse. In memorial at the end the war to Sir Guy Carleton filed by Nathaniel Moore of Newtown, Queens, he complained that he was unpaid for quartering of Captain Henry Elwes, commander of the grenadier company of the 22nd Regiment of Foot, when he billeted with him in Staten Island. He wrote,

That your Memorialist, in the Year 1776 Was an Inhabitant of Staten Island, in the Province of New York. That at that time, Capt. Elwes of his Majesty’s Twenty Second Regiment of foot Came with his Servant to The House of your Memorialist for Lodging and Entertainment in which he has furnished With at his Request.[13]

He continued,

That Your Memorialist has frequently requested Payment for the same from Capt. Elwes; But he has Neglected and Refused to pay. And the Only Answer which Your Memorialist Could Obtain was that he Remembered it, but would not Remember it.[14]

We do not know if the payment was ever made. Nathaniel Moore remained a Loyalist throughout the war and also accommodated Sir Henry Clinton at his house in Newtown in 1776.

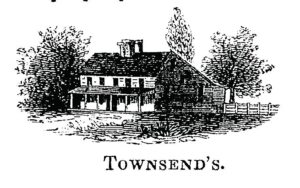

Discipline, routine and military chores went hand in hand with idleness for private soldiers and officers. Soldiers on Long Island left period graffiti on some of their places of accommodation. Officers quartered at Samuel Townsend’s house in Oyster Bay left their compliments to several of the local ladies that frequented the premises. They inscribed messages and initials into glass windows that remained in the house. Inscription and autographs show up as well in other period houses used by the British on Long Island.

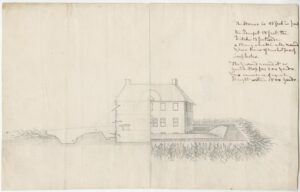

Some British officers set up their lodging as command posts. Commandeering and fortifying houses was not uncommon in the Revolutionary War, and suitable premises were confiscated and used as headquarters. This was the case in Jericho on Long Island when the home of Dr. James Townsend, brother of before-mentioned Samuel Townsend, was used as a temporary headquarters for the British commander. In Jericho the house and property were not only confiscated, but were also fortified.

Dr. James Townsend had been a member of the provincial congress prior to the enemy occupation of the island. An officer wrote to General Washington in 1778 of intelligence he had received from a subordinate who had clandestinely visited Long Island:

I this moment Recd a letter from Capt. Leavenworth who is from long Island this Morning. he informs me that Sir William Easkin with 350 horse and 300 Infantry is at Jerico on long Island, he has Turnd the Inhabitance out of dors to Barrack his troops, and is throwing up Works round Doctr Townsends Hous where he him Self Quarters[15]

Other houses are recorded to have been protected with field fortifications such as ditches, embankments, some sort of palisade surrounding the central fortified building. This was most likely the case in Jericho.

Hessian commanders on Long Island commandeered houses and fortified them with gun emplacements. Onderdonk wrote, “Col. Janecke was quartered at Dr. Lathams’, (now Judge Mitchell’s,) and had two swivels mounted before the house.”[17] Lieutenant-Colonel Ludwig von Wurmb, who commanded Hessian forces cantoned on northwestern Long Island in 1780, made his headquarters in Westbury. In front of his quarters a redoubt was built on a height, with a guard and two amusettes.[18]

As the war progressed, housing for displaced civilians and especially Loyalist’s from neighboring states also added to the challenge of finding quarters for British Forces. War torn communities were short on supply. The shortness of building materials and the continued need to preserve the supply chain made Long Island a constant hardship for the British occupiers.

Postscript: The author has located at least fifteen houses on Long Island which are still standing today that quartered British forces during the occupation. Modern development threatens many of them.

[1]Alexander McDougall to George Washington, January 11–15, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0683.

[2]John G. McCurdy, Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 13.

[4]Henry Onderdonk, Jr., Documents and Letters Intended to Illustrate the Revolutionary Incidents of Queens County: With Connecting Narratives, Explanatory Notes, and Additions(New York: Leavitt, Trow and Company, 1846), 133.

[6]W. Kelby, Great Britain Army Provincial Corps De Lancey’s Volunteers.Orderly Book of the Three Battalions of Loyalists Commanded by Brigadier-General Oliver De Lancey 1776-1778: To Which Is Appended a List of New York Loyalists in the City of New York during the War of the Revolution(Campbellville, ON: Global Heritage Press; 2008), 39.

[8]H. A. Stoutenburgh, A Documentary History of Het [the] Nederdeutsche Gemeente Dutch Congregation of Oyster Bay Queens County Island of Nassau Now Long Island(New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1906), 787.

[9]Elizabeth Drinker, The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker: The Life Cycle of an Eighteenth-Century Woman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 70.

[12]James Riker, Jr., The Annals of Newtown in Queens County, New York(New York: D. Fanshaw, 1852), 216.

[13]Nathaniel Moore of Long Island, farmer, to Sir Guy Carleton. (no date). Memorial, PRO 30/55/76/103 8593, British Headquarters Papers: 1747-1783, The National Archives, Kew, UK.

[15]Charles Scott to Washington, November 10, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0097.

[16]Lewis Lochee, Elements of Field Fortification (London: T. Cadell and T Egerton, 1783), 102-5.

[17]Onderdonk, Documents and Letters, 186.

[18]Johann von Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, ed. Joseph Philips Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 197), 250.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...