From the outset of the American Revolution and the outbreak of hostilities with Great Britain, a lingering problem that plagued the minds of the Continental Congress dealt with its financing. Under the Articles of Confederation adopted in 1777, Congress lacked the power to levy taxes.[1] Even had it possessed such power, to exercise it would risk losing popular support for the Revolution given that it was being waged largely over taxation issues to begin with. Without taxation as an option, the Continental Congress needed new methods of financing for both the daunting task of administering a newly-birthed nation, as well as financing a full scale war with the predominant military power of the age.

The generally-accepted and agreed-upon history of the colonies’ means of financing the American Revolution is primary accepted in the following narrative:

As the war for independence commenced, expenses quickly mounted and the Continental Congress began printing a new currency in order to finance itself and the war effort. Although there were plans to establish a mint at some point,[2] Congress had little choice but to rely on fiat paper money as the chief source of financing the Revolution during the war years. Although the young republic was issued some preliminary loans by France—eager to see the American rebels succeed in reducing Great Britain’s power by achieving independence—the loans were not sufficient to cover the full cost of the war,[3] and so the rebellious colonies and their congress were compelled to issue their own currencies.

The new dollars failed miserably as Congress printed copious amounts of them. There are clearly defined characteristics of sound money, chief among them being a good store of value and the ability to act as a medium of exchange, but the Continental (the term used to refer to Congress’s dollars) possessed neither. The notes were issued in such vast quantities that they quickly lost their value and became nearly worthless, putting the Revolution in peril as many questioned the integrity of the money. The currency failed as a medium of exchange, as those on the receiving end knew they were being given essentially worthless paper.

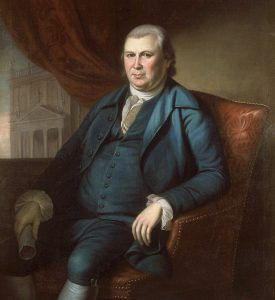

With Congress printing vast quantities of these Continentals, their value plummeted to the point of hyperinflation, as more and more dollars circulated competing for the same quantity of goods. Seeking to get their financial house in order, Congress appointed the Robert Morris, the wealthy Pennsylvania-based financier, as its Superintendent of Finance in 1781.[4] Understanding the connection between the republic’s struggles to finance itself and the rapidly devaluing Continental, Morris took corrective measures to both strengthen the dollar and cut expenses. Often using his own personal fortune to directly finance the Revolution and give General Washington crucial aid in times of need,[5] combined with his expertise in financial affairs and its appropriate application to the new republic’s dire financial situation, Morris was able to ensure that Congress remained solvent throughout the war, narrowly avoiding multiple financial calamities along the way. Such is the tale of financing the American Revolution.

There is, however, a much darker side of Revolutionary finance that is largely ignored by both scholars and the general public alike, and that is the issuance of commissary certificates by the Continental Army under Congress’s authority. These instruments of revolutionary finance were mainly deployed against the American people wherever and whenever the needs of the army were seen to outweigh citizens’ property rights, and they usually amounted to little more than a roundabout way for the Continental Army to simply seize provisions from civilians.[6]

Facing overwhelming odds and a slim chance at survival, the Continental Congress authorized the army under General Washington to seize provisions as needed; Washington and other senior leaders passed this power of seizure down to the Quartermaster Department.[7] Congress and the army justified the seizures by highlighting the dire situation of the Revolution, establishing a precedent that emergency situations superseded private property rights.[8] Congress took careful consideration to withhold its definition of what constituted such an emergency, knowing that it had to tread carefully when seizing property of the people it claimed to be liberating from British tyranny.[9]

During the initial stages of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army—under authorization from Congress—had the luxury of forestalling seizures against patriots, as there was no shortage of American loyalists from whom it could impress property.[10] States also began enacting their own legislation that allowed for the seizure of property from known loyalists, encouraged by Congress,[11] whereby the property was auctioned off and the funds put into the states’ coffers.[12]

Even from the American perspective, not everyone agreed with this practice. Immediately after the war, Alexander Hamilton often represented disaffected clients who had lost property through seizures in their lawsuits against the states to win the property back or obtain just compensation. He would go on, in the Federalist Papers, to discuss at length the importance of upholding private property.[13] Despite some objections against the blatant seizure of property, throughout the war years a considerable amount of confiscation took place in order to fund the Continental Army’s campaign expenses.

Each state had its own methods for seizing property from loyalists and others considered to be outlaws. Pennsylvania permitted seizures of foodstuffs that it believed to have been acquired through dishonest means, after which it was passed on to the Continental Army.[14] Virginia enacted strict profiteering laws targeting merchants who hoarded and resold at profit, enabling the legislature to seize goods at will from any who violated the laws.[15] The middle colonies enacted legislation against agriculture speculating, allowing them to seize grain, flour, or even money that was associated with agriculture insurance against crop failures.[16] In most agricultural cases, all of a farmer’s product above the minimum amount he needed for his own survival was subject to seizure.[17] New York was perhaps the most aggressive confiscator. In 1779 it passed what became known as the Forfeiture Act, which empowered the state government to seize property from anyone it deemed an enemy of the state, and thereafter banish that person from New York under penalty of death.[18] The Act was essentially a proscription list not too dissimilar to those found in Sulla’s Rome, even going so far as to list several citizens and Englishmen by name. Article II of the act read:

And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That the said several persons herein before particularly named, shall be and hereby are declared to be for ever banished from this State; and each and every of them, who shall at any time hereafter be found in any part of this State, shall be, and are hereby adjudged and declared guilty of felony, and shall suffer death as in cases of felony, without benefit of clergy.[19]

Although official legislation pertaining to property seizure only targeted loyalists and other dissident persons, patriot-sympathizing civilians also felt their effects as the army’s needs mounted. Purchasing agents for the Continental Army were supplied with a prescribed quantity of money earmarked for the procurement of supplies and provisions, to which they used in their dealings with merchants, farmers, and others. In light of Congress’s perilous financial situation during the war, the army’s purchasing agents were under orders to adhere to strict budgetary constraints when sourcing the army’s supplies.[20] Anyone in possession of goods needed by the army was subject to being approached by a purchasing agent from which he would sometimes be offered a sum of money in exchange for the goods. There were many instances where the army’s purchasing agents had no money, in which case the owner of goods were issued commissary certificates.[21] Furthermore, even when the army had money to offer the property holders, the purchasing agents were instructed to only offer a price which they deemed reasonable, and rarely did such price respect the current market conditions of supply and demand. If the property owner believed the army’s offer to be too low, his only choice was to either accept the cash or be issued commissary certificates.[22] It was a lose-lose situation, as the cash offer was paid out in rapidly depreciating currency, while the commissary certificates came with problems of their own.

Beginning in 1779, commissary certificates essentially replaced cash as the means of supplying the army with provisions. As hyperinflation set in, prices rose so high against the deteriorating dollar to the point that earmarked funds budgeted for specific purposes dried up long before their goals were achieved. In short, Congress had a true money problem, and commissary certificates became the primary means of acquiring goods from discontent citizens in order to meet the army’s needs.[23] As the army campaigned against the British, commissary certificates flooded the cities and countryside. People often compared the Continental Army with the British forces, as both seemed to employ similar methods of sustaining themselves. Little could be done in protest as each army took what it needed at the point of a bayonet, and from Congress’s point of view, people’s rights to property were subordinate to the needs of the army in an emergency situation.

The assault upon private property continued throughout 1779 and beyond, and the issuance of commissary certificates exacerbated Congress’s and the states’ abilities to seize goods. New York maintained pressure against the agriculture community, allowing Continental agents to purchase below market value or outright seize wheat, flour, and grain as they saw fit.[24] The following year, the state went one step further by ordaining that all wheat above basic subsistence levels were to be handed over to the Continental Army, and commissary certificates were to be issued as payment.[25]

Another common trick for the states during this time was to pass anti-monopoly and racketeering laws targeting merchants and speculators. The legislation would be carefully worded so that merchants and farmers were made out to be villainous Tories if they engaged in anti-patriotic market practices, thus making them liable for property seizure. Under these laws, the states would arbitrarily establish a legal price for various goods, and that price was usually far below the market-clearing equilibrium. The farmers and merchants couldn’t afford to realize losses by selling at those prices, but any attempt to sell above the mandated minimum would constitute a violation of the law, allowing local justices who had been empowered by the legislature to seize their wares.[26]

In May 1781, Lord Cornwallis and his command entered Virginia from the south after a protracted campaign in the Carolinas. Cornwallis’s entry into Virginia spelled trouble for the hapless citizens of that state, and the scale of grief inflicted upon the common man was as widely dealt by state legislature as it was by the British. By the time of the Yorktown campaign, Virginia had empowered its governor to procure whatever resources the war effort required, payable in certificates.[27] Any resource or material good deemed in excess of a family’s immediate need was subject to seizure or purchase via certificates, and the citizens had little choice but compliance. Congress had little real money with which to operate, and as a consequence, the entire military campaign in Virginia was financed through the seizure of goods via certificate issuance.[28]

Given how many commissary certificates were issued across the states by the Continental Army and its agents, a further investigation into the nature of these certificates is warranted. Although they had nominal face values, the eventual holder of the certificate often experienced the full negative consequences of Congress’s inflationary policy regarding the dollar. Those holding commissary certificates often experienced immeasurable difficulty redeeming them. The earlier debt certificates were simply hand-drawn notes signed by the agent and made out to the reluctant merchant or farmer losing his goods, with the transaction details often vague or insinuating. It wasn’t until later in the war that the certificates became more orderly and appeared in printed form.[29]

For the typical holder, collecting on a commissary certificate issued by the army proved to be an excruciating challenge. Congress was essentially bankrupt, therefore the certificates were backed by nothing more than a promise from a shaky, far-off government whose very existence was being threatened by the world’s predominant military machine. Worse still, the earlier certificates were not interest-bearing notes,[30] and there was no provision that protected the holder from hyperinflation. The face value remained unchanged as the holder eagerly hoped to one day receive payment for the goods that were taken, while hyperinflation destroyed the certificates’ nominal values.

The mass issuance of these commissary certificates backfired on the young republic in unpredictable ways as the Continental Congress and state governments discovered that the citizenry did not take kindly to being so heavily ripped off. Agricultural output from farming communities plummeted as farmers refused to plant anything in excess of what their immediate family needed, knowing that the army and its purchasing agents would simply confiscate the fruits of their labor and give them commissary notes in return.[31] People would often hide their property and hope they would escape notice, as the army passing through on campaign would confiscate anything it deemed useful to the war effort: beef, grain, horses, wagons, munitions, linen, and other supplies, issuing commissary certificates wherever it went. There were many instances were the army almost disbanded for want of supplies, and so the certificates were viewed as a desperate measure to save the army from destruction, their issuance being a necessity.[32] The army did however “pay” more generously in certificates to those willing to surrender their goods, while those who held out more reluctantly were treated with proportional harshness.[33]

The mass issuance of these certificates became a source of friction between the new government of the United States and the people towards the end of the war as Congress attempted currency reform. Holding commissary certificates and understanding to some degree that they may never receive proper redemption should the United States fail, people sought to use their certificates to satisfy any tax obligations they had,[34] essentially circling back the notes to the original issuer. Congress and the state governments, still needing hard cash to finance their expenses, found themselves collecting commissary certificates in lieu of funds they needed to carry on the struggle against Great Britain.

American citizens insisted on paying their tax obligations with certificates when applicable, and the state governments were in no position to refuse. The people’s insistence created a bind for state governments, as it would be hypocritical for the states to refuse accepting payment in their own debt. The Continental Army had the incentive, however, to keep the certificates outstanding as long as possible. Given that the certificates were issued in lieu of payment for impressed goods, and also given that they bore no interest, the issuer could sit back and watch the certificates’ value rapidly depreciate in the holders’ hands as inflation chipped away at their worth.

Commissary certificates were a dark stain on Revolutionary finance, undermining the moral and philosophical justification of the Revolution. Ordinary people, seeking to be free of all kinds of tyranny, found themselves being plundered from all sides as competing forces coveted their resources. The mass issuance of the notes severely undermined congressional attempts at currency reform, further undermining the revolution. With so many certificates circulating, and with those certificates being a valid form of payment for tax obligations, states found themselves ingesting the notes rather than hard cash, and Congress struggled to retire some of its near-worthless currency in an effort to get inflation under control. Eventually, many of the commissary certificates would be redeemed at a fraction of their original value, and the certificates would be retired and absorbed into the national debt of the young United States. But for those individuals who were compelled to surrender their property in exchange for these certificates during the years of conflict, one might say they are entitled to halfhearted gratitude from a grateful nation for performing a compulsory, sacrificial, and patriotic duty at liberty’s expense.

[1]Articles of Confederation; 3/1/1781; Miscellaneous Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789; Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, Record Group 360; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[2]Robert Morris to Congress, January 15, 1782. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “1782 January-June” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

[3]Samuel Flagg Bemis, “Payment of the French Loans to the United States, 1777-1795,” Current History (1916-1940) 23, no. 6 (1926): 824–31.

[4]Robert Morris to the President of Congress, July 17, 1781, The Papers of Robert Morris, E. James Ferguson, ed. (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973), 1:397-402.

[5]Morris to George Washington, The Papers of Robert Morris, 1: 213-216.

[6]James E. Pfander, “History and State Suability: An ‘Explanatory’ Account of the Eleventh Amendment,” Cornell Law Review 83, no. 5 (July 1998): 1270–1382.

[7]Colonel Clement Biddle Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I: 8, 15, 19, 21.

[9]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789(Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 10:273.

[10]Howard Pashman, “The People’s Property Law: A Step Toward Building a New Legal Order in Revolutionary New York,” Law and History Review Vol. 31, no. 3 (August 2013): 587-626.

[11]Journals of the Continental Congress, 7:75-78.

[12]Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature Held in the Years 1777-1784, Vol. 1. 1st session, ch.34, (Albany: Secretary of State, 1886), 173-75.

[13]Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Papers No. 22(New York: Dutton/Signet, 2012).

[14]Wilbur Siebert, The Loyalists of Pennsylvania (Columbus, OH: The University at Columbus, 1905), 68.

[15]William Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia Vol. 10 (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, 1822), 233-37.

[16]James T. Mitchell and Henry Flanders, ed., The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 Vol. 9 (Harrisburg: C.M. Busch, 1903), 421.

[17]Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature Held in the Years 1777-1784, Vol. 1. 1st session, ch.34 (Albany: Secretary of State, 1886), 71-73.

[20]Edmund Burnett, ed., Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, Issue 299, Vol. V (1931), 326-327.

[23]E. James Ferguson, The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance, 1776–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 61.

[24]Laws of the State of New York, 92-94.

[26]Maryland Session Laws, November, 1779. ch. XVII.

[27]Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large, 233-37.

[28]Timothy Pickering papers, Ms. N-708, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[29]Pfander, “History and State Suability”: 1270–1382.

[31]William Reed, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847), 2:224.

[32]Journals of the Continental Congress, 10:273.

[33]Francis Wharton, ed., The Revolutionary Correspondenceof the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), 4:676.

[34]Ron Michener, “Backing Theories and the Currencies of Eighteenth-Century America: A Comment,” The Journal of Economic History 48, no. 3 (September 1988): 682–692.

Recent Articles

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

Recent Comments

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

It seems there is no way to know the details of the...