A recent trip to the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia unearthed the institution’s continued shift towards presenting narratives and stories that most students—and adults—are unfamiliar with. When images of the era are discussed, one would be correct to assume the museum’s focus centers on the Washingtons, Hamiltons, and Franklins of lore, and no doubt they have their respective places. But what may surprise many is the breadth with which the museum continues to spotlight minority voices from the past, and rightfully weaves their stories into the greater early American experience. Look no further than the current exhibit on James Forten, one of Philadelphia’s most distinguished and important citizens.

The Forten family is one of the truly remarkable ancestries of early America. A mulatto free woman named Sarah Fortune born in Somerset County, Maryland, was likely the child of an enslaved father and a white indentured servant mother. Her son, Thomas Fortune, was born in 1740, and the family had relocated to Philadelphia by the mid-eighteenth century. Thomas’s sister, Ann Elizabeth Fortune, left him a considerable estate in her will in 1768.[1] Thomas Fortune or Forten, along with his wife Margaret Waymouth, would have two children: Abigail and James.

Born on September 2, 1766, young James grew up along the docks of the Delaware River as Thomas worked in the local sail loft of Robert Bridges. The two had worked side by side as apprentices until Bridges bought his own business and brought Forten with him.[2] Thomas died in 1773, leaving Margaret Forten few options for maintaining a household. James received a brief education from neighbor and friend, the emerging abolitionist Anthony Benezet, before having to find work to support the household. Benezet found him a job with a local grocer, giving the now-literate boy a means to support his mother and sister.

On July 8, 1776, a curious nine year old James found himself among a large crowd outside the Pennsylvania State House. There read aloud for the first time was the Declaration of Independence. He spoke of the incident for the rest of his life with admiration. Five years later, James served his country aboard the privateer Royal Louis, a 450-ton ship armed with twenty-two cannon and a crew of 200.[3] Captained by Stephen Decatur, James was a cabin boy, a shot carrier (retrieving munitions from the shot locker), and generally a lower-level grunt beginning in July 1781. The first trip of Royal Louis was plentiful. They captured several prizes before returning to Philadelphia in August. One encounter with the British naval sloop of war Active was a serious fight. Most of the Royal Louis gunners were killed by cannon fire. The returning privateers were greeted on the Philadelphia wharves with loud “huzzahs!”[4] On September 2, while celebrating his fifteenth birthday, James watched in awe as General Washington, along with most of the Continental army, marched through Philadelphia on their way to Virginia.[5] Forten later recalled how the “several Companies of Colored People, as brave Men as ever fought” inspired him.[6]

Royal Louis, along with two smaller ships, set sail in the following weeks. Reports of British and French warships crowding the mid-Atlantic coast continued to trickle in. Decatur, thinking he found a window to safely exit the Delaware Bay, was spotted by the British warship Amphion. Captained by a seasoned sailor, John Bazely, Amphion was a vessel weighing 679 tons with thirty-two cannon.[7] She was joined by La Nymphe, a captured thirty-two gun French warship captained by John Ford. Bazely chose to pursue Royal Louis while Ford went after the other two, the brig Molly and the schooner Raccoon.[8] Bazely initially raised French colors to try and dupe the American privateer, but Decatur smelled the rat. A seven hour chase then ensued with Royal Louis meeting her fate off the coast of Hampton, Virginia on October 8. Finally caught up to her, Bazely fired several shots that the experienced Decatur knew meant his end. He promptly surrendered. La Nymphe soon returned with her two prizes in tow. In the coming days, the crew of Royal Louis was divided among the three captured ships.

Forten remained aboard Bazely’s Amphion as the ship made way for New York. He would later recall his “mind was harassed with the most painful forebodings” as he was more than aware Black sailors were often sent to the Caribbean into slavery. However, fate interceded for James Forten. Accompanying Captain Bazely were his two sons of twelve and fourteen: his youngest Henry had little to do onboard and was a nuisance. Needing a companion, it was Captain Bazely who spotted Forten among his captives, and liking what he saw, assigned him to Henry. But it was a game of marbles that sealed his fate. Henry was so impressed by Forten’s ability at the game he approached his father and called Forten to repeat his skill for the captain, which he did several times. Coupled with discovering that the young cabin boy was literate, Captain Bazely now took an interest in him. In the coming days, Forten won special treatment among the prisoners. So much so that Bazely offered Forten the chance to accompany Henry back to England where he would receive a wealthy education as a free man. It was a remarkable gesture. However, in Forten’s own words, he replied, “I have been taken prisoner for the liberties of my country, and never will prove a traitor to her interest.”[9]

Thus, James Forten sailed into Brooklyn Harbor and on the evening of October 23, 1781, he was recorded into the muster book of the infamous prison ship Jersey as prisoner 4102. Bazely wrote a letter to the ship’s commandant praising Forten and wishing he not be forgotten when his time for exchange was called. Regardless, Forten was now crammed aboard one of the Revolution’s most notorious vessels. During the day, prisoners were allowed to roam atop on deck. At night, they were forced below into cramped, stinking quarters with whatever effects they might have. Some had blankets they used for beds. The fate of sailors onboard came down to their time served and when they might be exchanged for captured British seamen. In the meantime, smallpox, dysentery, parasitic bugs, starvation and mental collapse were the real threats to each prisoner. Though few attempted it, the idea of swimming to shore made little sense: New York City and Long Island were fully under British control. Locals were most likely Tories and would return any escapee for a reward. Despite the risks, Forten hatched a plan to escape. A Naval officer onboard Jersey was about to be exchanged, and Forten gained permission to hide in his sea chest. At the last minute, Forten gave up his spot to fellow prisoner Daniel Brewton, a white Philadelphian. The act of kindness would be the start of a lifelong friendship between the two veterans.[10]

Seven long months passed before James Forten’s name was called and he was told that he was being exchanged. What had partially delayed him and his fellow seamen was that American privateersmen taken as prisoners of war were not considered legitimate military prisoners in the eyes of the British government. Recall, the American Revolution was considered a rebellion from Parliament’s viewpoint; privateers from an illegitimate belligerent were seen as no more than mere pirates, but fears of retaliation left their fate precariously unresolved. It wasn’t until March 1782, after Lord North’s government fell and the tenor of the war shifted to securing a peace treaty, that Parliament finally recognized naval captives as legitimate prisoners of war.[11]

Emaciated, barefoot, and his hair falling out in clumps, James Forten walked from New York to Trenton, New Jersey, where local citizens gave him shoes and food. He soon returned to Philadelphia where his mother and sister were stunned to see him alive. Margaret Forten had assumed he was dead after newspaper reports had given the fate of the Royal Louis months ago. Forten would regain his strength and soon find a job working for Robert Bridges, the sailmaker who employed his father.

All of this would make a great museum exhibit in its own right, but this is far from the end of the story of James Forten. By the 1790s, Forten had steadily climbed through the ranks at Bridges’ loft to be head foreman and then manager of the business. His abilities, knowledge and leadership were proven. In 1798, Bridges retired and approached Forten to buy him out. With the assistance of Philadelphia’s Thomas Willing, Forten soon owned the enterprise. By 1810, Forten’s sailmaking business was one of Philadelphia’s most profitable. As such, it made him the wealthiest African American in the country. In return, Forten went out of his way to employ both black and white laborers, and was heralded by Philadelphians for his generosity and his philanthropy. Yet it was the lingering exhaustive institution of slavery that became the outlet of Forten’s time and resources, and would define his legacy.

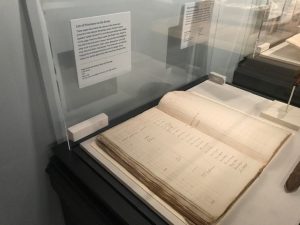

The Museum of the American Revolution’s exhibit “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia” presents James Forten through this lens, one of Revolutionary upbringing and service that transpired into a lucrative profession that afforded him the means to fight against the injustices of slavery in the United States. The exhibit spends great care and effort touching on not just his involvement with funding the newspaper, the Liberator, but also how his devotion to America, and its ideals, fueled a lifetime of activism, and produced a family of generations of gifted, outspoken and dutiful servants to the cause of abolition and freedom. The exhibit is a full dive into the century between 1776-1876 that is sprinkled with top notch artifacts, including the muster book of the Jersey that shows Forten’s name,[12] the original copy of Pennsylvania’s 1780 emancipation law, and artifacts showing the tenuous struggle throughout the nineteenth century in a racially polarized Philadelphia. But make no mistake, this exhibit is about one family buoyed by legacy, pride and purpose. It is these individual stories of family, tradition and service that bespeak the influences of a patriarch who first heard the very words of the Declaration of Independence at its debut reading, and then sought to hold the country he loved to task. All because a boy joined a curious crowd in July 1776.

We in the historical community continue to make great strides in bringing forward individuals and their stories that show how unique America has always been. No more is it simply a monotonous vestige of dusty black and white narratives. My own continued journey of learning — and wishing I had learned these stories in grade school — gives me encouragement as we expand our modern perceptions of who and what it was to be an American in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. My work with the American Battlefield Trust was focused specifically on bringing forward as many stories as we could find, including that of James Forten, for students.

And reading Forten, who later in life fumed how “It is a well known fact, that black people, on certain days of publick jubilee, dare not be seen after twelve o’clock in the day, upon the field to enjoy the times, for no sooner do the fumes of that potent devil, Liquor, mount into the brain, than the poor black is assailed like the destroying Hyena or the avaricious Wolf,”[13]how do we square this with what he witnessed in July 1776, and what he did thereafter as a lifelong patriot? We owe ourselves, as Americans, to understandthe past, and know the sacrifices these people made in the name of liberty.

“Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia” runs through November 2023 at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. Special thanks to Curator of Exhibitions Matthew Skic, Chief Historian Phil Mead, and Director of Communications Alex McKechnie for their generosity with their time and assistance.

[1]Ann Elizabeth Fortune was involved in Philadelphia’s slave trade, likely explaining her accumulated wealth. Anthony Benezet served as her executor of her estate, and Hannah Cadwalader, mother of Lambert and General John Cadwalader, served as a witness. David Hackett Fischer, African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals, 203-205.

[3]Julie Winch, A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002), 37.

[5]Artist Don Troiani created his painting, “Brave Men as Ever Fought,” from the quote by James Forten.

[6]Fischer, African Founders, 258.

[7]Captain John Bazely had recently assisted in the Battle of Groton Heights or the burning of New London, Connecticut, on September 6, 1781.

[8]Winch, A Gentleman of Color, 41-43.

[12]The Jerseymuster book is on loan from the British National Archives. It has not been on American soil since 1783.

4 Comments

Excellent read. It is always beneficial to continue inviting a more diverse cast of characters into the complicated narrative of the American founding.

Shawn,

Thank you for reading and enjoying it. I agree. Forten’s story stands out for all the obvious reasons, and adds a much needed layer to the era showing success against the odds, and the continued complications of the racial divide that went unresolved by the Revolution’s ideals.

This is absolutely wonderful! Thank you so much for sharing this story of Mr. Forten! What an amazing man!

Aaron,

Thank you for reading and enjoying the article. Indeed, his story is one of the most profound of the era.