On the second day of 1780, Capt. Silas Burbank of the 12th Massachusetts Regiment sat down to record a deposition from William Walker, a private soldier in the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment. Walker wasn’t sure if he was in trouble, but after losing £2,561 worth of clothing destined for the Continental Army wintering in Morristown, he certainly had to explain himself.

Walker had been in the army for three years, enlisting in January 1777 for the duration of the war. As he left no pension application and only late-war muster rolls remain that record his name, it is difficult to determine what he did from 1777 to 1780, but the tale he told Captain Burbank would certainly rank among his most unique wartime experiences.

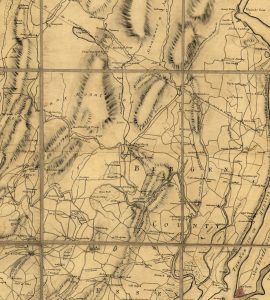

Walker left Fishkill Depot on Christmas Day 1779, taking “one two horse Sleigh for General Greene QMG [Quartermaster General] to carry to Morris Town” clothing for the troops. He was to travel south to Verplanck Point “and to go the route of Kings Ferry between the hours of nine & Ten oClock in the forenoon.” Walker loaded the “Baggage, Sleigh and Horses in the Boat to cross the River, where Liuet. Grant ordered” them to take their goods out again, to instead load the boat with oxen. Frustrated, Walker obeyed orders “when the Boatmen turned everything on Shore [and] I was obliged to wait until evening when Mr. Grant then ordered me to cross the River.”

The crossing went routinely enough until they neared the Stony Point side of the ferry, when “a body of Ice came down the river against the Boat.” The ferryman “jumped on shore in order to save the Boat,” but Walker “was obliged to save my own life and Horses.” He jumped or was knocked into the icy Hudson River, “driving with the ice near to my arm pitts and jumped the Horses out of the Boat by which means I saved my own life and my Horses but also my Sleigh & Harness and Baggage went off in the Boat which we could not save and further saith not.”[1]

Just like that, Walker, through no fault of his own, lost all the baggage intended for Morristown. He made it back to Fishkill a few days later where he delivered his deposition. What exactly was lost among the baggage? Before Walker left Fishkill on Christmas Day, Lt. Col. Udny Hay, the Deputy Quartermaster General, had an invoice drawn up. The baggage included:

1 Ps [Piece] Green Broad Cloth Containing £ s d

26 yds at 32£ pr yd 832

1 Ps Claret do [ditto] Containing

32 ¼ yards at 32£ pr yd 1032

1 Ps Mixt do Containing

18 ½ yds at 32£ pr yd 592

3 ¾ do French Thread at 12£ pr do 45

2 do Colored do at 20 pr do 40

11 oz White do at do do 13 25

10 oz Twist at 10£ do 6 5

2561 “ 0 “ 0”

Walker gave his mark (as he was likely illiterate) and affirmed he would deliver the clothing to General Greene. As we know, it drifted down the Hudson, and we don’t know that it was ever recovered.[2]

Lt. Col. Hay enclosed the receipt and Walker’s account in a letter to General Greene on January 3, 1780, noting that “the misfortune that happened in its transportation across at Kings Ferry as will appear by the enclosed affidavit is as far as I can yet totally owing to the accident, a more accurate enquiry how ever shall be made.” Days later, Hay wrote back to Greene after receiving some of Greene’s letter written the week before. Hay had told Greene “some days ago of the misfortune which attended the cloathing . . . in its passage across Kings Ferry.”

Luckily for Walker, Hay was unable to “find it was in any degree owing to negligence or design.” William Walker was off the hook. Hay continued that he “had several complaints from Kings Ferry lately, many of them I am afraid to be well grounded, the ferrymen there are without doubt a sett of as great banditte as ever existed.” He explained this behavior as “for want of better men we were under the necessity of enticing them again to reinlist and for that purpose allow them many liberties which at any other time would by no means have been granted.”

William Walker returned to duty as a waggoner out of Fishkill, a job he maintained consistently without joining his regiment through the rest of 1780 and as least as late as April 1781, where muster records for him end. Hopefully, the rest of Walker’s deliveries were more routine.[3]

[1]Return of Burr’s Company, 2nd Massachusetts Regiment, September 9, 1778, fold3.com/image/17240186; Deposition of William Walker, January 2, 1780, Papers of the Continental Congress: Letters from Nathaniel Greene, with Various Papers Relating to the Quartermaster’s Department, 1778-1780, fold3.com/image/352034. Hereafter noted as PCC (Papers of the Continental Congress). The author was unable to identify Lieutenant Grant.

[2]Invoice of Clothing forwarded by Udny Hay DQMG to the Honorable M. General Greene QMG, December 25, 1779, PCC, fold3.com/image/352036.

[3]Udny Hay to Nathaniel Greene, January 3, 1780, PCC, fold3.com/image/352031; Udny Hay to Nathaniel Greene, January 9, 1780, PCC, fold3.com/image/352041. The author was unable to determine what unit was operating King’s Ferry during Walker’s episode, nor whether they were Continental, state levies, or militia units. William Walker January-June 1780 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/1724023; William Walker April 1781 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/17240214.

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...