The Royal Navy was designed not just protect the island of Britain and its commerce, but to project Great Britain’s power across the seas. Britain’s success as a sea power led to the creation of a large overseas empire and, by the latter half of the eighteenth century, naval dominance of the Atlantic world. One of the Royal Navy’s organizing principles during the age of sail was the notion of a stand-up sea battle, where numbers of ships on both sides lined up against one another, blasting away with their broadsides. In confronting its rebellious North American colonies this approach proved unworkable, for the simple reason that, through their long reliance on the Royal Navy for safety, the Americans were incapable of floating such a navy themselves. Instead, the rebels’ strategy was to avoid British naval strength, and instead pick away at their enemy, guerilla style, with small vessels, privateers and coastal defenses. The Royal Navy needed to adapt by expanding the number of their ships which could function in a shallow coastal and riverine environment.

Fortunately for Britain, in the period between the Seven Years War and the American rebellion, the Admiralty had dusted off and updated an earlier design for a medium size warship with substantial armament that could perform well on the coast of North America. Designed in 1769, His Majesty’s Ship Roebuck was constructed at Chatham Dockyard, at a leisurely pace between 1770 and 1774, initially under the direction of Surveyor of the Navy, Sir Thomas Slade. Built along the general lines of the Phoenix, which had been in service since 1759, Roebuckwas a fifth rate: a 44-gun, two-deck warship, too small for a ship of the line, yet too large to be called a frigate.[1]

Commissioned as Roebuck’s captain was thirty-six-year-old Andrew Snape Hamond, the son of a merchant ship owner, who had joined the Navy at age fifteen, and who achieved command of a series of increasingly powerful ships. By the time he was twenty-one, he was a lieutenant aboard the 64-gun Magnamine, proving his mettle in the British victory over the French at Quiberon Bay under Capt. Richard Howe, the man who would become his chief supporter. By 1775, Hamond had served as commanding officer of six other ships, including the 90-gun, second rate, Barfleur. Moving to a 44-gun ship might seem a reduction in stature, but Hamond was soon to be placed in command of a squadron of smaller ships.[2]

When war broke out, Roebuck was sent to join the fleet attempting to maintain British rule in the colonies. She arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia at the end of October 1775 and was soon put to good use, establishing a blockade in the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. Quickly recognizing Roebuck’s utility, the Royal Navy ordered more ships of similar design for service in the American war, the first of which, Romulus, began construction in May 1776.[3]

On arrival in the Chesapeake, Hamond took command of several ships already serving there to assist the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, who had fled for safety aboard the sixth rate Fowey. Shortly after arrival, Hamond fitted out a sloop to act as a tender, which he named Lord Howe in honor of his patron. Each of the warships in his squadron was supported by at least one tender, which served as a link to shore for communication and supplies, and could also be used to pursue small enemy ships seeking refuge in the shallows.[4]

Hamond’s initial orders were “to Guard the Entrance of the River Delaware . . . to use your utmost endeavours to prevent any Supplies getting to the Rebels, to annoy them by all means in your Power, and to protect and defend the persons and property of His Majesty’s Loyal and Obedient Subjects wherever they can be distinguished.” Philadelphia, 100 miles upriver from the sea, had become the center of the American military’s logistical efforts. When it became apparent that Pennsylvania was building naval vessels and placing obstructions in the river to defend the city, Hamond received amended instructions: “You are hereby required and directed, to do your utmost to destroy those Floating Batteries, and to Weight up or otherwise render useless the Machines sunk in the Channel of the said River.” This turned out to be a challenging assignment.[5]

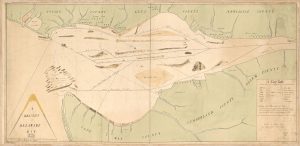

In mid-March, expecting the Delaware to be free of ice, Hamond left a few ships to assist Dunmore and manage the Chesapeake blockade, and sailed for the Delaware Capes. The river itself was a hazardous place. Its numerous creeks concealed shallow-draft armed vessels while hostile militia infested its shores. Sailing in the area was made more dangerous by a combination of shoals and tides that could vary the river’s depth by five to six feet in a few hours. In places, even at the mouth of the Bay, depths were sometimes as shallow as a single fathom – six feet. Hamond later commented, “I don’t know any river so difficult of navigation.” Experienced pilots were needed to guide ships through the narrow channels, and the Americans did their best to keep such pilots out of British hands.[6]

While Hamond’s Delaware squadron succeeded in seizing numerous merchant vessels and sinking many others, they also faced a number of setbacks. On March 28, Roebuck’s 3rd lieutenant, George Ball, and several seamen were made prisoners when their boat ran aground while chasing a ship. Roebuck herself ran aground more than once, and had to be hauled off the shoals by her boats and tenders.[7]

A particular problem was the Overfalls, a large area of submerged muck just south of the Jersey Cape where the passage over the bar was only fifteen feet deep. Savvy merchantmen and privateers played a cat and mouse game with the British squadron, hugging the shallow eastern side of the bay and slipping out to sea between the Overfalls and Cape May. Hamond tried anchoring off this area to intercept enemy traffic, but lost his anchor in the “quicksand” for his pains. In a typical episode, Capt. John Barry brought his 14-gun brig, Lexington, down the bay at the end of March and, though sighted and chased by Roebuck, was able to escape out to sea when darkness fell.[8]

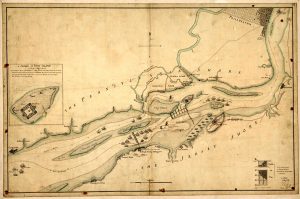

Nonetheless, Roebuck and her tiny fleet were able to capture several prizes and destroy a number of other ships between March and early May. On May 4, Hamond decided it was time to make his way up the Delaware, in company with the frigate Liverpool, a brig, Betsey, and their tenders, to investigate the reported defenses and to draw fresh water. They had gotten seventy-five miles upriver, by the 7th, when they chased a schooner which ran for Wilmington Creek, but got aground and stuck fast. While British boats were busy unloading the schooner’s cargo of bread and flour, thirteen row galleys of the Pennsylvania Navy dropped down the river to attack them, accompanied by a 10-gun floating battery and a sloop fitted as a fire ship. Each galley carried a large cannon, between eighteen and thirty-two pounds, in its bow. In the course of three hours, the ships exchanged between 300 and 400 shots, though neither side suffered significant damage.[9]

As the ships fired on one another, curious spectators lined the shore, along with several companies of soldiers, both local militia and Pennsylvania riflemen, anxious for an opportunity enter the fray. An American schooner, Wasp, took advantage of the confusion to sally out of Wilmington Creek and, under the enemy’s guns, snatched the brig Betsey. At that moment, Roebuck went aground off Carney’s Point on the Jersey side, and the gallies closed in, hoping to capture it. While the Liverpool came to anchor to protect Hamond’s ship, Wasp sent the captured brig downstream, out of British hands.[10]

The British situation through the night was perilous. Hamond was particularly concerned about fire ships being sent down to burn his immobile vessel. He gave detailed instructions to the others on protecting Roebuck, his orders assuming a desperate tone: “whoever shall distinguish himself in the performance of any Service under my command may rely most fully upon my unwearied endeavours to obtain them ample rewards for their merit; And on the other hand to assure him that, every neglect will be as strictly enquired after.”[11]

To his relief, Roebuck was refloated about 4:00 AM. When the morning fog lifted, Hamond’s squadron pursued the row gallies upriver, but abandoned the chase when the wind died, preferring to drop back down to where the river was less constricted and they could maneuver better against the enemy if they should follow. While in his journal he put the best face he could on the affair, he broke off the engagement in clear recognition of the hazards presented by the river’s defenses: “not having a force with me sufficient to authorize me to attempt to force the fortified pass of the River, I consulted with Captain Bellew [of the Liverpool], who agreed with me in opinion, that it would answer no good purpose to go further up the River, which every mile made more intricate.” During the battle, Roebuck lost one man killed and several others wounded, had her rigging damaged and was hulled several times, receiving as many as forty balls from the gallies.[12]

Learning of the British move against Charlestown, South Carolina, Hamond left Liverpool to maintain the Delaware blockade and sailed south, intending to lend support to Commodore Peter Parker’s squadron on the Carolina coast. On his way, he found that Governor Dunmore was in serious trouble, as the Americans assembled a force to attack him near Norfolk:

I have been under the absolute necessity of giving to Lord Dunmore & his floating Town, consisting of a Fleet of upwards of 90 Sail, destitute of allmost every material to Navigate them, as well as seamen, has given full employment for three Ships, for these three month past, to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Enemy

Dunmore’s force sought refuge further up the Chesapeake at Gwynn Island, hoping its resources could sustain the exiles. The site turned out to lack fresh water and was militarily untenable. The Americans set up batteries opposite the island and drove the British off in early July. Disease was rampant in the Chesapeake at the time. Dunmore’s men suffered dreadfully, as did the shipboard sailors and marines of Hamond’s squadron.[13]

His crew badly depleted, Hamond nevertheless joined in the invasion of New York in August, participating in several ship-to-shore actions in the waters around the city in support of Gen. William Howe’s operations. In October, General Howe ordered an expedition up the Hudson to interdict supplies coming downriver to the American force on Manhattan Island. The flotilla of six ships, including Roebuck, had to pass between a pair of forts and maneuver around sunken obstacles at the Narrows, where the George Washington Bridge stands today. Bombarded for ninety minutes without slowing to engage the forts, the ships suffered considerable damage, though none were disabled. Roebuck alone had five men killed and another seven wounded. The mission to disrupt American shipping was successful, but Hamond absorbed another ominous lesson about the dangers presented by American river defenses. The experience was to have a significant impact on the following year’s campaign.[14]

British plans for the invasion of New York were largely effective, despite the concurrent northern invasion via the Lake Champlain corridor sputtering to a halt. The poor coordination between army and navy experienced the previous year had been remedied by the appointment of Lord Richard Howe to command the Royal Navy in North America. Lord Howe, the elder brother, worked closely with his counterpart, Commander in Chief William Howe, both on military operations and the brothers’ other assignment as Peace Commissioners, charged with bringing about a settlement with the rebellious colonies.

General Howe faced off against one of the greatest leaders of his age, George Washington, a man who wrote extensively and who consulted openly with political leaders and subordinates. The secretive Howe’s image suffers by comparison. Taciturn to a fault, both in word and in writing, the reasoning behind his decisions is often unknown and unknowable, subject to speculation which generally casts him in a bad light, particularly because, though he won nearly every battle, his strategy for the 1776 and 1777 campaigns failed to subdue the revolt. Political partisanship, jealousy and hurt feelings generated many critiques in the aftermath, which continue to shape writers’ opinions down to the present day.

In preparing for 1777, the Howe brothers still believed their best chance to quash the rebellion lay in destroying Washington’s army. By moving against the American capital and military supply center at Philadelphia, General Howe hoped to draw the rebels into open battle—an action where Britain’s military superiority would prove decisive.

General Howe’s initial plan, unfolded to Hamond in a confidential dispatch by his commander, Admiral Howe, was “to land the Army as high up the [Delaware] River as possible.” Hamond assured the admiral that he could lead the fleet to a landing place above New Castle, posting small vessels along the river’s course to mark the shoals. But the Royal Navy’s combat experiences on the Delaware and Hudson troubled General Howe. Aware of the potential for disaster, the general decided by June that he would not risk an opposed landing on the Delaware, but would instead make his way up the Chesapeake Bay, where American defenses were negligible. The distance between the two landing areas was minimal, and the Chesapeake site had the added advantage that it threatened Washington’s supply bases in Pennsylvania—Lancaster, Reading, York and Carlisle. Cautiously, General Howe confided this new plan only to his brother—even his closest aides were kept in the dark about his actual destination.[15]

Meanwhile, late in 1776, Roebuck and her squadron had been ordered to cruise the Delaware Capes again. The British fleet rendezvoused with Hamond there on July 30, 1777. Summoned aboard the flagship, Eagle, Hamond engaged in a brief conversation with the Howe brothers. Those without knowledge of the general’s plan believed that, at this meeting, Hamond ill-advisedly convinced the Howes to avoid a Delaware landing. This was far from accurate. Hamond did describe the dangers of defending against the shallow-draft Pennsylvania Navy, complemented by its numerous fire ships, in a shoaly, constricted space. Instead, he counseled them to land lower downriver, near Reedy Island, forty-five miles below Philadelphia, where there was more room for the warships to maneuver. But he was surprised to learn that day from Admiral Howe that his brother the general had already determined, before the meeting, to shift their landing place to the Chesapeake. Hamond reported that the admiral had told him “that the General’s wishes & intentions were first to destroy the magazines at York & Carlisle before he attacked the Rebel Army or looked towards Philadelphia; and therefore it was of a great object to get to westward of the Enemy.”[16]

Unfortunately for the British fleet and the soldiers aboard the transports, that would mean travelling another 230 miles before landing. Hamond was given the honor of leading the fleet to the Elk River in Maryland. Due to adverse winds, the troops didn’t disembark until August 25. Landing off Reedy Island, about fifty-five miles up the Delaware from the sea, might have allowed up to three additional weeks for campaigning. In the end, the overland distance between the Elk River and a landing site near Reedy Island was only seventeen miles. Despite the cost in lost time and discomfort for the ship-board troops, the Howes had avoided potential catastrophe—the Chesapeake landing was uncontested.

Perhaps realizing that time had grown short, and that Washington’s army might come between him and his supply source at the Head of Elk, General Howe abandoned his plan to strike at York and Carlisle. Instead, he attacked and defeated the Americans at Brandywine. After maneuvering and fighting a series of smaller battles, the British army finally marched into Philadelphia a month later on September 26. Still in the field despite heavy losses, the rebel army rebounded with an attack at Germantown, surprising the British with their resilience. In the face of a determined enemy restricting access to forage and food, Howe needed to supply his troops and feed the occupied city’s populace by opening the Delaware navigation. This proved to be a hard nut to crack—complex, laborious and hazardous.

At the best of times, piloting ships through the Delaware shoals was a tricky prospect. Now, sunken obstacles called chevaux de frise blocked the channel in several places. Chevaux were long poles lodged in boxes, weighted down with fifteen to twenty tons of rock, their iron tips lurking a few feet beneath the surface, waiting to puncture and sink any vessel attempting to pass over them. On October 4, ships’ boats from Roebuck and others began the time-consuming work of removing the lower set of obstructions, across from a partially completed fort at Billingsport. Trying to navigate in these treacherous waters, often under fire, the British warships operating among the mud banks and shallow channels frequently ran aground and had to work their way off by warping or being towed.[17]

After opening a narrow passage, the scene of operations then shifted north toward the final row of chevaux, just downriver from Delaware’s muddy confluence with the Schuylkill River. These obstructions were guarded not only by the ships and gallies of the Pennsylvania Navy, but by a pair of defensive works, Fort Mifflin on Mud Island to the west, and Fort Mercer at Red Bank on the Jersey side—fortifications that had to be reduced before work could begin.[18]

Late on the afternoon of October 22, 900 Hessians attacked the Jersey fort, which was held by 600 Americans. When Pennsylvania’s gallies joined in the action, bombarding the German soldiers, the British ships which had passed above the Billingsport chevaux moved to engage them, with the 64-gun ship of the line, Augusta, in the lead. In the urgency of the moment, Roebuck came charging past the 18-gun sloop, Merlin, ordering her out of the way. As Merlin came about and readied her forecastle guns for action, she ran onto a mud bar and stuck fast. Exchanging fire with the Americans, Augusta too grounded on the bar, just as the river’s tide began to ebb. Ominously, she could not be worked loose. Roebuck, and a few other ships, with their boats, positioned themselves between the stranded ship and the enemy. They struggled through the night to free Augusta, but were unsuccessful.[19]

Next morning, Pennsylvania’s fleet closed in again, firing on Augusta for several hours until the warship finally caught fire. Realizing the fire would inevitably reach her magazines, Roebuck and the other ships did their best to rescue Augusta’s crew before retiring downriver, out of range of the expected detonation. The nearby Merlin was also evacuated in anticipation of the coming blast. She was set afire to prevent her capture. A little before noon, Augusta blew up in a tremendous explosion, which shook the ground for miles around.[20]

Though Hamond’s journal did not record Roebuck’s damage from this engagement, she seems to have been hit several times. The Commodore of Pennsylvania’s fleet, John Hazelwood, observed that “Besides the 64 & Frigate being burnt, the Roebuck who lay to cover them we damag’d much & drove off, & had she laid fast, we shou’d have had her in the same situation.” Another American letter reported her as “exceedingly shattered.” Hazelwood was later informed by Royal Navy deserters that Roebuck had suffered six killed and ten wounded in the action.[21]

The British spent the next three weeks bombarding Fort Mifflin from their shore batteries in Pennsylvania. In mid-November, several warships, including Roebuck, moved up to attack, while a pair of shallow-draft gunships, Vigilant and Fury, anchored in the back channel and battered the defenses from close range. This combined force pounded the fort into submission, and it was finally abandoned the night of November 15, the garrison escaping across the river to Red Bank.[22]

Over the next several weeks, boats from Roebuck and the other ships labored to remove enough of the chevaux to allow supply ships to sail up to Philadelphia. The obstacles nonetheless remained a navigation hazard. Liverpool was badly damaged while attempting to remove them, and the victualer Juliana was pierced and sunk on December 1. It took twelve days to refloat her off the chevaux and most of her cargo was spoiled.[23]

A reprieve from their constant cruising now ensued for Captain Hamond and his crew. Roebuck was one of four ships stationed in the river off Philadelphia during the winter of British occupation. Though many Philadelphia residents went hungry, the army and navy were relatively well supplied and comfortable. In the Spring, Hamond hosted an elaborate dinner for General Howe before his departure from America. “I gave the General a Ball and supper on board the Roebuck, where 200 Ladies and Officers sat down to supper and danced until Day light in the morning.” A few days later, Roebuck occupied a position of honor during the Mischianza, an extravagant celebration in honor of General Howe, during which the ship sported “the Admiral’s flag hoisted at the foretop-mast-head.”[24]

Roebuck remained active in 1778 and 1779. In 1780, Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot selected her as his flagship, to lead the naval operations against Charlestown. Three days after Charlestown’s surrender, Hamond sailed for England, where he went on to a distinguished career in the Admiralty. He had not enjoyed the Roebuck’s service in American waters, noting by 1776 that he that he had become, “most heartily tired of carrying on this sort of Piratical War, that tended in no degree to benefit his Majestys service.”[25]

Roebuck returned to British waters in July, 1781. During the following years, she acted in various capacities, as a troop ship, a hospital ship and a receiving ship, before finally being broken up at Sheerness in 1811, having served for thirty-six years. As an indication of success during her first two years, Roebuck received full or partial credit for twenty-seven prizes in 1776 alone, and twenty-two more in 1777, ending up with a total of seventy-four prizes during the American Revolution. She had served the Royal Navy credibly in her attempts to enforce the blockade on the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, so much so that nineteen more ships of the Roebuck class were built during the war. She had been well led. An impartial observer, who had opportunity to witness Captain Hamond’s leadership personally, commented that he was “the best man in the Navy.” Many others tended to agree.[26]

[1]Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714-1792: Design, Constructions, Careers and Fates (Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing, 2007) 176. Three Decks – Warships in the Age of Sail: threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=6230.

[2]Three Decks – Warships in the Age of Sail: threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_crewman&id=1380.

[3]Samuel Graves to Andrew Snape Hamond, December 13, 1775, in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 13 volumes (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962 -) 3:84 (NDAR). Winfield, British Warships, 176.

[4]Journal of HMS Roebuck, February 16, 1776, NDAR 3:1324.

[5]Samuel Graves to Hamond, December 25, 1775, NDAR 3:235. Molyneux Shuldham to Hamond, January 17, 1776, NDAR3:834.

[6]Hamond to William Dunmore, March 14, 1776, NDAR 4:343. The Detail and Conduct of the American War, Under Generals Gage, Howe, Burgoyne, and Vice Admiral Lord Howe (London: Richardson and Urquhart, 1780) 71.

[7]Journal of HMS Roebuck, March 29-31, 1776, NDAR 4:595-597.

[8]Journal of HMS Roebuck, March 31, 1776, NDAR 4:597n11. Henry Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 1, 1776, NDAR 4:618. Lexington turned the tables a few days later by engaging and capturing the Liverpool’s tender, Edward. New York Journal, April 18, 1776, NDAR4:772.

[9]Journal of HMS Roebuck, May 4-7, 1776, NDAR4:1446-1447. Colonel Samuel Miles to Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, May 8, 1776, NDAR 4:1466.

[10]Autobiography of Joshua Barney, May 7-8, 1776, NDAR 4:1467.

[11]Hamond to Henry Bellew, May 8, 1776, NDAR 4:1469.

[12]Hamond to Bellew, May 8, 1776, NDAR 4:1467-1469. Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, May 9, 1776, NDAR 5:15-16. Deposition of William Barry, June 11, 1776, NDAR 5:481-485. Deposition of John Emmes, June 29, 1776, NDAR 5:665-669.

[13]Hamond to Peter Parker, June 10, 1776, NDAR 5:460-461. Hamond to Hans Stanley, August 5, 1776, NDAR 6:66.

[14]Journal of HMS Phoenix, October 9, 1776, NDAR 6:1178-1180. Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, October 9, 17776, NDAR6:1182-1183.

[15]Andrew Snape Hamond, Autobiography, Vol. 2:4, quoted in NDAR 9:83. Friedrich von Muenchhausen, At General Howe’s Side, 1776-1778, The Diary of General William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen, trans. Ernst Kipping, ed. Samuel Smith (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 21.

[16]Richard Howe to Philip Stephens, December 12, 1776, NDAR 7:460-461. Journal of Ambrose Serle, NDAR9:327. Journal of HMS Roebuck, July 30, 1777,NDAR9:354. Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, July 31, 1777, NDAR9:363.

[17]Master’s Journal of HMS Roebuck, October 4, 1777, NDAR 10:39.

[18]Rand Mirante, A Visit to Old Fort Mercer on the Delaware, Journal of the American Revolution, August 9, 2018 allthingsliberty.com/2018/08/a-visit-to-old-fort-mercer-on-the-delaware/. Rand Mirante, A Visit to Old Fort Mifflin on the Delaware, Journal of the American Revolution, August 6, 2020 allthingsliberty.com/2020/08/a-visit-to-fort-mifflin-on-the-delaware/.

[19]Court-Martial of Commander Samuel Reeve, R.N., November 26, 1777, NDAR 10:607-610.

[20]Master’s Journal of HMS Roebuck, October 23, 1777, NDAR 10:246. The Journals of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, Volume III, October 23, 1777 (Philadelphia: The Evangelical Lutheran Ministerium of Pennsylvania, 1958), 91.

[21]John Hazelwood to George Washington, October 23, 1777, founders.archives.gov/?q=%20Recipient%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22%20Dates-From%3A1777-10-23%20Dates-To%3A1777-10-27&s=1111311111&r=3. John Hazelwood to Thomas Wharton, Jr., October 29, 1777, NDAR10:343-344. Joshua Blewer, Pennsylvania State Navy Board to Thomas Wharton, Jr., October 30, 1777, NDAR 10:359-360. Anonymous letter reported in Independent Chronicle, November 21, 1777, NDAR 10:342.

[22]Journal of John André, November 15, 1777, NDAR10:500. Johann von Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, trans. Ed. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 104-105.

[23]Journal of HMS Liverpool, November 1, 1777, NDAR10:370-371. Richard Howe to Hamond, December 2, 1777, NDAR 10:653-654. Journal of Captain James Parker, December 1, 1777, NDAR10:645.

[24]William Faden, A Plan of the City and Environs of Philadelphia(London: 1779), collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:q524nb41d. Autobiography of Andrew Snape Hamond, quoted in John W. Jackson, With the British Army in Philadelphia, 1777-1778 (San Rafael: Presidio Press, 1979), 238. John Andre, “Particulars of the Mischianza exhibited on America at the Departure of Gen. Howe”, Gentleman’s Magazine 48 (1778), 353.

[25]Hamond to Stanley, September 24, 1776, NDAR6:973.

[26]“Prizes” in HMS Roebuck (1774), en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Roebuck_(1774). This list was assembled by an anonymous editor from contemporary notices in the London Gazette. Three Decks – Warships in the Age of Sail: threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_class&id=193. James Cunningham’s Examination, 18th July, 1776, NDAR5:1137.

6 Comments

Bob:

Very interesting article on a little-known aspect of the American Revolution’s riverine warfare.

Thank you for this excellent piece on the riveting saga of HMS Roebuck (and incidentally for the citation as well)! I wonder if you might consider a companion article focused on Hamond, who seems to have had a compelling career outside the bounds of this essay (Lunenburg raid/Nova Scotia governorship, commandant at Nore, Bounty court martial, etc)? Also, out of curiosity, what is the date of the tidal map you provide and who drafted it? – couldn’t make it out on my iPad.

Reid,

You can see a high quality version of the map here:

https://www.loc.gov/item/gm72003568/

It says: Drawn by Richard Taylor for Cast. Jann, Philadelphia, and was probably done during or more likely shortly after the British occupation. Supposedly it was based on soundings actually taken by Hamond’s squadron. Hamond would be an excellent subject for an article.

I read it three times — Great Chronology!

Over the years, I have been researching various aspects of Hammond’s actions on the Delaware.

I had visited the David Library of the Revolution and read the microfilms. I was trying to find who were his intelligence operatives. Hamond was tight lipped on naming names. I suspect Joseph Galloway fed him intelligence.

Sheriff of Philadelphia during the British occupation, Galloway was one who also did not mention the names of his spies.

Back in England a narcissistic Galloway made many complaints against General Howe’s actions in Philadelphia.

Thanks for a great read and the excellent research.

J.M.

Outstanding article and great research. As one who has given numerous presentations to local audiences at various locations up and down the Delaware Bay and River, each covering parts of what your article covers, I will recommend it for further reading at the end of each talk. Thank you for helping me remind our citizens of “Delaware’s Naval Heritage.”

Jacob Jones was an American naval Hero of 1812. It was his observations of the actions of Hamond and his forces while a boy in Lewes that stirred in him the desire to become a naval officer. One might say Hamond was Jones mentor.

Excellent article, Bob! Can’t wait to play a wargame scenario on the fight for the Delaware. Thanks for a very interesting piece. – DB