Tucked away in George Washington’s papers rests a thirty-five-page handwritten folio labeled “Forms of Writing.”[1] In Washington’s neat and ornate cursive, the first roughly two-thirds of this artifact are comprised of carefully copied examples of legal mechanisms such as promissory notes, bills of exchange, short- and long-form wills, and, ominously, a “Form of a Servants Indenture.”[2] Clearly whoever directed the young Virginian to transcribe this legalese felt it to the boy’s advantage to have a working understanding of the litigious environment he would likely soon enter. Also included are two poems, “On Christmas Day” and “True Happiness.”[3] Historians once attributed these compositions to Washington; more recent scholarship definitively traced them to 1743 and 1734 editions, respectively, of Gentleman’s Magazine, a London periodical.[4]

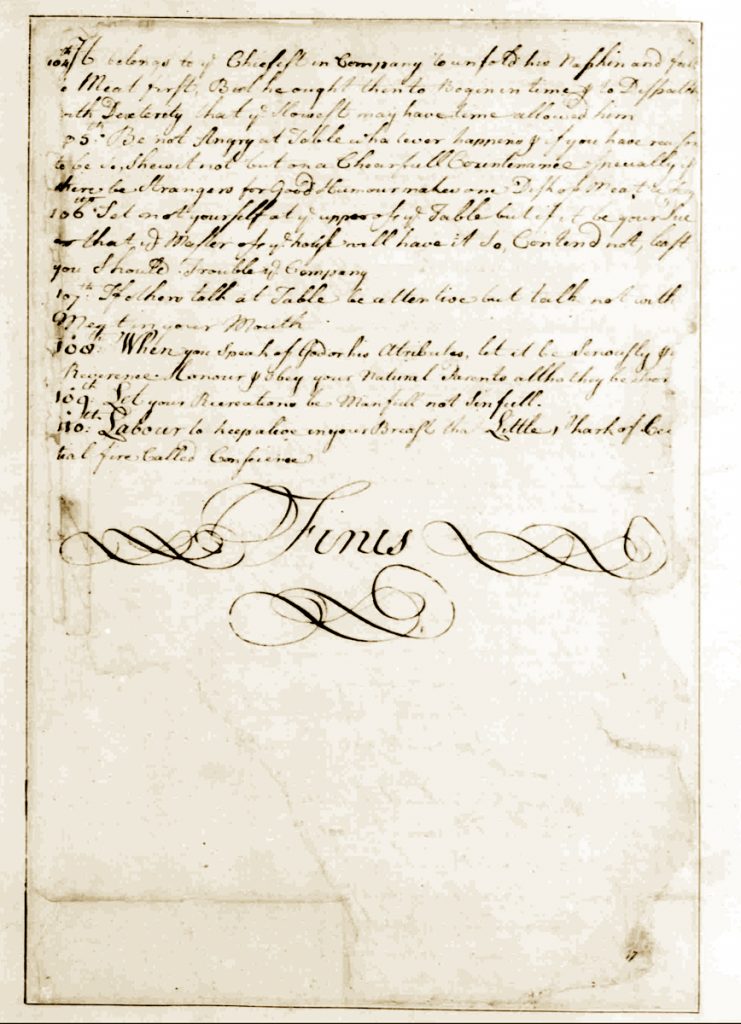

This collection of Washington’s papers dates to early in his life: in the upper-righthand corner of the twenty-first page, another writer scribbled “Geo. Washington’s handwriting in 1744 at the age of 12.”[5] Within the text of one passage, Washington copied the year “1741,” while on the seventh page, he wrote “my hand and seal this Day of April, Anno Dom 1743.”[6] Since these dates are within passages he was transcribing, however, they are likely less reliable than the year recorded in the foreign hand for dating these papers with any degree of certainty. It is the final ten pages of this manuscript, however, that have piqued the interest of some scholars. George Washington’s “Notes of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation,” a compilation of 110 instructions in etiquette and ethics, remains something of a literary mystery.[7] Just where the maxims originated, how they ended up before Washington and what purpose(s) they served, is not entirely clear. The circumstances that produced these papers, however, moved Washington to sponsor educational initiatives at the provincial and national levels both privately and publicly. Scholastic cultivation, Washington came to appreciate, promoted private achievement and the public good, vital contributions to both individual and national success. Taken together, Washington’s own acknowledged academic shortcomings led him to identify equitable access to education as a fundamental component for promoting civic virtue, American identity and national security.

I

Washington’s earliest biographers took little to no notice of his “Notes of Civility.” John Marshall’s multi-volume adulatory survey (1804-1807) fails to recognize the maxims, with the chief justice summarizing Washington’s education as simply “limited to subjects strictly useful.”[8] Mason Weems, in a book one early editor described as an “absurd” contribution to American historiography, made no mention of them in his 1808 publication.[9] In 1842, Jared Sparks, that ambitious if less-than-meticulous scholar, determined the notes originated from various sources that an adolescent Washington ultimately failed to cite.[10] Washington Irving theorized the young Virginian composed the rules himself to assimilate into the refined household of the Fairfax family his older half-brother Lawrence had married into.[11] In 1888, Dr. J. M. Toner transcribed and published the first full transcription of “Rules of Civility” with limited editorial amendments. He only noted, through use of several ellipses, where lost text from the original pages had been eaten away by mice. After fruitlessly searching the Library of Congress for any books and/or treatises on manners and morality dated 1745 or earlier, Toner determined the maxims “were compiled by George Washington himself when a school-boy.” Toner also recognized that Washington’s compositions embodied the spirit of Europe’s polite society while simultaneously claiming the rules remained “especially applicable” to British North America.[12] How a struggling Virginia boy might have learned of and valued Old World cosmopolitanism the scholar left unanswered. Even as thorough a historian as Paul Leicester Ford simply offered, in passing, that Washington’s biographers credited the Virginian with composing “Notes of Civility.”[13] Uncharacteristically, the scrupulous Ford provided no further analysis. It was not until eccentric Virginia scholar Moncure D. Conway grew curious about these papers that this mystery began revealing its secrets.[14]

Toner’s short treatise sparked Conway’s interest in exploring further the origins of “Notes of Civility.” When Conway began researching a domestic biography of Washington he scoured the municipal records of Fredericksburg, Virginia, a village the Washingtons had moved within the vicinage of when George was about six. Conway discovered that French settlers had founded that town’s first school and Rector James Marye, also an emigrant from France, had presided over St. George’s Church, the first such institution in Fredericksburg. This led Conway to reasonably suspect that Marye had taught Washington at St. George’s and the rules were likely French in origin. Conway divulged these suspicions to a friend at the British Museum who subsequently directed the scholar to an old manuscript written in both French and Latin. Within that archaic tome Conway located most of Washington’s rules. Incredibly, this discovery marked just the beginning of Conway’s investigation.[15]

Conway uncovered a complicated cultural tale that stretched back into late sixteenth-century France. In 1595, the College of La Fleché, a Jesuit institute of higher learning, sent neighboring College at Pont-á-Mousson a treatise entitled “Bienseance de la Conversation entre les Hommes,” which translates roughly to “Good Manners in Conversation Between Men.”[16] This brief manuscript contained loose French versions of ninety-two of Washington’s hitherto elusive “Rules of Civility.” It is not clear why La Fleché sent this work to Pont-á-Mousson, but a local bishop next ordered “Bienseance de la Conversation” translated into Latin. In 1617, Pont-á-Mousson reproduced the work and these French directives underwent subsequent printings in both Paris and Rouen. Scholars eventually translated the treatise “into Spanish, German, and Bohemian,” initiatives expressive of the wider European application and polite universality this collection of maxims held. Conway determined that educators had copied this manuscript for the exclusive use of university students where it made its way into print.[17] Both the spiritual and secular themes suggest the author(s) designed these directives to indoctrinate upper-class boys with the appropriate piety and performative virtue with which to aspire.

Conway proved a careful scholar, discovering that eighteen of Washington’s rules were not from the pages of “Bienseance de la Conversation.” Fortuitously, he learned of an English translation that contained all of the missing maxims. In 1640, eight-year-old Francis Hawkins, according to the publication, translated and published the French instructions as Youth’s Behavior, or Decency in Conversation Amongst Men. Conway remained unconvinced of the author’s proposed age, which, according to a later scholar, clouded the Virginian’s judgment and estimation of Hawkins’s work.[18] That aside, by 1646 the book had gone through four editions; by 1663, a mysterious “counsellor of the Middle Temple” had added twenty-five new rules. Conway found that this edition actually included thirty-one new maxims, six more than its title page boasted.[19]

Conway connected these disparate times, tongues, and towns into a plausible synthesis. According to the historian, after James Marye converted from Catholicism to Protestantism in 1726, his family disowned him. This familial ostracism compelled Marye to relocate to England where he met and married Letitia Maria Anne Staige. Incredibly, Staige’s brother presided over St. George’s church in Virginia, prompting the couple to emigrate to the Old Dominion. In 1735 Marye became minister at St. George’s, a position he maintained until 1767. Conway reasoned that Marye had established and taught at a small country school, surmising the intrepid Frenchman had brought a copy of “Bienseance de la Conversation” to England and then purchased Youth’s Behavior before departing for Virginia.[20] In his final analysis, Conway doubted “whether the Virginia boy used the work of the London boy.” He concluded Washington had likely written these maxims down as oral exercises administered by Marye, who used both the French and English versions to craft an amalgamation of both treatises.[21]

In 1926, Charles Moore, head of the Division of Manuscripts for the Library of Congress, published a new transcription of Washington’s “Rules of Civility” and included a convenient comparison with the 1663 edition of Youth’s Behavior.[22] Surveying the available literature, Moore remarked of the shadowy maxims, “much has been written and little is known.” He also addressed Conway’s reluctance in believing that eight-year-old Francis Hawkins had personally translated the French rules into English. The Hawkins family, Moore uncovered, descended from an old and learned aristocratic family and Francis’s father John had already published five books before his talented young son translated “Bienseance” into English. John, proud of his son’s advanced linguistic abilities, delivered the work to printer William Lee, who published it as Youth’s Behavior in 1640. The chaos of the English civil wars prevented a second edition from being printed until 1646, after which the book rapidly ran through numerous editions. Unknown English writers, explained Moore, added more maxims over subsequent printings; the 1663 copy, however, contains every rule found in Washington’s manuscript. This indicates that under whatever circumstances Washington produced his version, he must have had access to the contents of either the 1663 edition of Hawkins’s work or a later form of the same. Moore concluded that a comparison of Washington’s manuscript “furnishes proof positive” that the maxims came from Youth’s Behavior and not “Bienseance.” Moore further theorized that some unknown figure selected, synthesized and situated the specific 110 rules for professional or private purposes. This unique composite found its way into Washington’s possession and the boy copied them, Moore conjectured, as “exercises in handwriting.”[23]

Modern scholars have spilled less ink on Washington’s “Rules of Civility.” John Ferling offered only that the maxims, which he claimed Washington “found somewhere,” helped the Virginian develop his courtly manners and modesty.[24] According to Joseph Ellis, Washington likely used them more for penmanship exercises than moral instruction.[25] Over two volumes on Washington, Peter R. Henriques mentioned the rules just once. Contradicting Ellis, he argued that at least the final maxim, which urges readers to “keep alive in your Breast that Little Spark of Celestial fire Called Conscience,” played a greater role in settling Washington’s own conscience than did any “ministers, priests, prophets, or holy books.”[26] Gordon Wood connected Washington’s rules to the Virginian’s desire of becoming a liberal gentleman “aware of the conventions of civility.”[27] In addition to embodying the social etiquette required to navigate virtually any polite environment, Wood explained that eighteenth-century gentlemen continually refined their penmanship, grammar, and spelling. And unlike Old World gentlemen, who were effectively rewarded by birth and rank, American cosmopolitanism flowered from individual merit and effort.[28] No doubt all of the preceding observations fit into the social context of this mystery.

Despite some anomalies, Washington almost certainly referenced the 1663 edition of Youth’s Behavior while drafting his own “Notes of Civility.” Hawkins’s work is divided into seven chapters, each beginning at rule one and totaling 173 maxims.[29] The chapters are organized by theme: the appropriate behavior among men; conversational protocol; addressing persons of various ranks; clothing maintenance and personal hygiene; walking alone or in company; body language during discourse; and dining etiquette.[30] Washington’s copybook, on the other hand, advertises no such topical divisions, begins at maxim one and continues to 110, never again starting at maxim one as Hawkins’ chapters do. The Virginian’s version also omits fifty rules outright while combining several others into single instructions.[31] Additionally, Washington copied three directives from the unnumbered additions included in the 1663 edition of Youth’s Behavior. Yet even considering these omissions and combinations, Washington’s manuscript follows Hawkins’ work faithfully in terms of sequence. For example, Washington began with Youth’s Behavior, chapter one, rule one, but omitted Hawkins’ second rule and skipped to the third. Thus the Virginian’s second maxim, as it were, reflected the Englishman’s third. Washington’s copy does not bounce between chapters or ever go out of order; though he ignored or joined some maxims, what he copied follows perfectly the general chronology of Hawkins’ work. This alone is powerful evidence that the Virginia boy worked exclusively with some version of Youth’s Behavior.

Curiously, not a single rule in Washington’s version is copied identically from the Hawkins folio. Each maxim is recognizable to the degree that scholars can confidently identify Youth’s Behavior as the source material, but nearly every directive in the Washington manuscript is considerably shorter than its seventeenth-century counterpart.[32] Below are three examples representative of this observation:

Washington, Rule 1:

Every Action done in Company, ought to be with Some Sign of Respect, to those that are Present.

Hawkins, Chapter 1, Number 1:

Every Action done in the view of the world, ought to be accompanied with some sign of reverence, which one beareth to all who are present.

Washington, Rule 25:

Superfluous Complements and all Affection of Ceremonie are to be avoided, yet where due they are not to be neglected.

Hawkins, Chapter 2, Number 1:

Although superfluous Complements, and all affectation in Ceremonies are to be eschewed, yet thou oughtest not to leave them which are due, otherwise thou displeasest the person with whom thou dost converse.

Washington, Rule 28:

If any one come to Speak to you while you are Sitting Stand up tho he be your Inferiour, and when you Present Seats let it be to every one according to his Degree.

Hawkins, Chapter 2, Number 5:

If any one come to speak with thee whilst thou sittest; stand up, especially if the person do merit it, be it that he be greater than thy self; or for that he is not familiar, or though for the rest he were thy equal, or thy inferior: and if there be any thing for one to sit on, be it a chair, be it a stool, give to each one his due.[33]

It is unlikely that a school-aged Washington took it upon himself to synthesize the meandering language of Youth’s Behavior into the cleaner, clearer prose reflected in his copybook; his typical dense verbiage conspicuously supports this observation. It is equally unlikely that James Marye, a native French speaker, rearranged the convoluted seventeenth-century maxims into the more condensed English instructions found in Washington’s manuscript.[34] Of course this complicates the matter at hand and leaves open some limited possibilities as to how Washington created his “Rules of Civility.” Either some unknown person: A) selected and copied the 110 rules they felt most valuable for ingraining a cultural acumen among students and Washington had these drafts before him or attended training under this person; or B) some unknown person had the Hawkins copy and verbally dictated improvised abridgements to his students as recitation and memory exercises, which may explain why Washington followed Youth’s Behavior sequentially despite omitting and combining certain maxims.

The purpose(s) of these papers is equally unknown. Moncure D. Conway melodramatically declared these directives provided “the art and mystery of moral education” to a man who once dictated the future of “the New World, — in a sense, human destiny.” The maxims, he remarked, “celebrate self-restraint, modesty, habitual consideration of others, and, to a large extent, living for others.”[35] For Dr. J. M Toner, the rules contained the essential “habits, morals, and manners” that shaped Washington’s “noble character.”[36] As noted above, Charles Moore and Joseph Ellis viewed the rules as nothing more than mundane handwriting exercises. Instead of considering these written directives as either vital for instilling morality or critical for perfecting penmanship, it is perhaps more useful to combine these potential intentions. A young eighteenth-century gentleman, after all, would have absorbed the behavioral instructions he was copying while simultaneously perfecting his letters in an effort to realize his maximum potential as a budding intellectual.

Literature promoting model behavior and conversational decorum enjoyed a wide audience in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and in British North America during the eighteenth century.[37] This genre of writing is perhaps most famously exemplified by Baldassare Castiglione’s 1528 Book of the Courtier, which may have inspired the original authors of “Bienseance de la Conversation” to write that French treatise in the first place.[38] Much of this literature, moreover, advocated the mastery of intellectual, moral and physical qualities. These instructions in gentility, contained in a manuscript like Washington’s “Rules,” ultimately extended to the tangible advantages of copying them.

Historians may never identify the person(s) responsible for educating Washington. There are, however, several suspects scholars may reasonably entertain. Washington’s father Augustine received a partial education at the Appleby Grammar School in England during his brief childhood stay in the metropole.[39] Obviously satisfied with his experience, he made certain that elder sons Lawrence and Augustine, Jr., each received their schooling at the same institution.[40] Additionally, according to Virginia Rev. Jonathan Boucher, an indentured servant provided at least part of George’s education.[41] Any of the four individuals listed above could have become familiar with the Hawkins maxims and, either in an English classroom or private quarters, copied the rules while updating the language. It is also possible that Lawrence, Augustine, Jr., or the aforementioned unknown teacher dictated a personal synthesis of the 110 maxims to an adolescent George. The record as it stands simply does not allow for definitive closure regarding this matter.

II

During Washington’s long career, he mixed with some of the most educated and creative minds in public life. In comparison with these associates, Washington identified his own education as quite basic, leaving him underinformed or even ignorant on a range of subjects. Lacking command of a foreign language, for instance, offered no small degree of discomfort to him.[42] Washington’s sensitivity over his academic shortcomings also caused him to agonize over his public correspondence. When Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie read Major Washington’s account of his 1753 expedition to Fort Le Boeuf, for example, the governor demanded its immediate publication. This left the young officer with but a single day to craft his minutes into a readable synthesis. Unnerved by what he considered an unpolished final draft, Washington opened his treatise with a brief disclaimer, explaining he could only “apologize . . . for the numberless Imperfections” contained in his journal. Washington quite reasonably explained he had no time to “correct or amend” his narrative under the circumstances.[43] As general of the Continental forces, he left much of his military correspondence to secretaries. Otherwise, according to Timothy Pickering, he would spend hours correcting the mistakes of a single letter.[44] Indeed, early in the war Washington requested a “good Writer, and a Methodical Man” for a clerk. He claimed the demands on his time prevented him from keeping up with his correspondence, making “it is absolutely necessary . . . for me to have person’s that can think for me.”[45] As president, he hounded cabinet members to help him write his formal addresses to Congress and further pestered other confidants to proofread them.[46] Public perception remained important to Washington and he aimed to disguise his personal vulnerabilities whenever possible. He proceeded with additional caution when his public letters might potentially expose his country education.

After the American War for Independence, Washington’s secretary David Humphreys expressed his “ardent desire to see a good history of the Revolution” personally written by the commander in chief.[47] “I am conscious of a defective education,” Washington responded, “and want of capacity to fit me for such an undertaking.” The general declared Humphreys uniquely positioned for the task and offered his former secretary an apartment, access to his papers and “any oral information of circumstances . . . that my memory will furnish.”[48] Humphreys rose to the occasion and wrote Life of General Washington with the Virginian’s close cooperation.[49] In response to the manuscript, Washington scribbled comments and criticisms to correct or complete various passages with which he took issue. One passage that escaped any such remarks, tellingly, involved the general’s mysterious education; Humphreys credited Washington’s limited schooling simply to a “domestic tutor.”[50] The master of Mount Vernon, apparently comfortable with this description, offered no further direction.

Washington’s self-described “defective education” drove him to help others avoid the academic inferiority he felt so deeply.[51] After learning a friend’s son wished to attend the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), Washington pledged a £25 annual stipend to help defray the boy’s tuition. He rationalized that a good education would “not only promote [the young student’s] happiness, but the future welfare of others” as well.[52] When strategizing son-in-law John Parke’s continued education, Washington wrote to prospective tutor Jonathan Boucher that he wanted the boy to learn French to “become part of polite Education.” The acquisition of that Romance language, he wrote, was vital for anyone hoping to attend to public affairs. “The principles of Philosophy,” he added, also remained “very desirable knowledge for a Gentleman.”[53] When the Maryland legislature chartered Washington College in 1782, the general pledged that institution fifty guineas and joined its Board of Visitors and Governors.[54] Washington likewise gifted Liberty Hall Academy (now Washington and Lee University) one-hundred shares of the James River Company to underwrite prospective students’ tuition. This generous contribution equated to about $20,000 in eighteenth-century currency and is still providing a modest subsidy to students in the twenty-first century.[55]

As president of the United States, Washington began connecting education with the future security and stability of the nascent nation. On January 8, 1790, he delivered before the House and Senate his “First Annual Message to Congress.” Surveying the state of the union, the president advised legislators to provide for the common defense of America by investing in public education and the production of military hardware. “Knowledge is in every country,” the president proclaimed, “the surest basis of public happiness.” Informed Americans, he lectured, bolstered “the security of a free Constitution,” as citizens knowledgeable of their rights transformed into vigilant sentries better able to “discriminate the spirit of Liberty from that of licentiousness.”[56] In a letter published in the Gazette of the United States, one observer encouraged Congress to support Washington’s educational patronage by promoting literature rather than attempting to “controul and shackle it.” Congress might achieve this, he offered, by establishing federal professorships for history, civics and law at every American university. This observer suggested that the president of the United States should personally appoint all federal professors. He expected these trusted academics to educate citizens about their liberties, “the grand American revolution” and the mechanics of the federal republic. The writer reasoned that graduates exposed to this form of virtuous curriculum would mix with all levels of society and disseminate their wisdom to the benefit of the entire political community.[57]

In Washington’s final annual message to Congress, he again stressed the relationship between national security and education. The federal government, he declared, must promote civic cultivation to accelerate “the assimilation of the principles, opinions and manners” of all Americans. “The more homogeneous our Citizens can be made,” thundered the president, “the greater will be our prospect of permanent Union.” To accomplish this, he again urged Congress to support and fund educational initiatives focusing on civic virtue. He asked, “In a Republic, what species of knowledge is more important . . . to those, who are to be the future guardians of the liberties of the Country?”[58]

President Washington likely expected his carefully crafted “Farewell Address” to be the final time he commanded a public audience to engage with his vision of the republic’s future. In that message, he warned Americans that virtue remained the “necessary spring of popular government.” In order to preserve the constitution and guarantee the nation’s future, Washington asked Americans to support institutions that promoted the general diffusion of knowledge. “In proportion as the structure of government gives force to public opinion,” he advised, “it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.”[59] Washington clearly felt the nation’s survival depended on an informed citizenry. He grew concerned that if the political community did not share similar civic values, the social fabric of American life would fray and the republic would descend into something reminiscent of the chaotic 1780s.

Despite George Washington’s heroic private and public support of education, his peers often remarked in less-than-favorable terms about his intellectual abilities. According to Rev. Jonathan Boucher, once a close friend of the American general, Washington “had no other education than reading, writing and accounts, which he was taught by a convict servant whom his father bought for a schoolmaster.”[60] Aaron Burr condemned Washington as a “Man of no Talents . . . who could not spell a Sentence of common English.”[61] Despite offering some kind words, Thomas Jefferson claimed Washington possessed “neither copiousness of ideas, nor fluency of words” and if called on suddenly “was unready, short, and embarrassed.”[62] Timothy Pickering cast Washington off as “So ignorant, that he had never read any Thing . . . [and] could not write A Sentence of Grammar, nor Spell his words.” John Adams offered an even less flattering picture, claiming Washington “was too illiterate, unlearned, [and] unread, for his Station and reputation.”[63] These isolated remarks, of course, only draw out the origins of Washington’s educational activism and speak little of its results.

What motivated Washington to promote education evolved over the course of his long career. He harbored a deep sensitivity to his own limited academic exposure, of which crafting “Notes of Civility” was a result. This experience compelled Washington to actively advocate liberal access to education. Following the rise of the republic, his support for civic instruction took the form of a public-spirited crusade. Washington determined that only an educated people could sustain the republican empire of liberty. Any political community dependent upon robust civic participation for its survival, the old revolutionary came to realize, must be certain its participants are politically informed, intellectually engaged and cognizant of their shared future. In short, republicanism depended on academic cultivation; anarchy and tyranny thrived in ignorance and fear. Washington put forth a sustained and herculean effort to entice the political nation to choose the former path. If Americans chose the latter, the president feared, they would become the architects of their own destruction.

[1]This paper resulted from Journal of the American Revolution editor Don Hagist’s curiosity into this subject. Any flaws in these pages are mine alone; any valuable insights resulted from his initial query. George Washington, George Washington Papers, Series 1, Exercise Books, Diaries, and Surveys-99, Subseries 1A, Exercise Books -1747: Forms of Writing, and The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation, ante 1747. Ante 1747. Manuscript/Mixed Material. The Washington Papers, www.loc.gov/item/mgw1a.001/.

[4]Gentleman’s Magazine, February 1743, February 1734; See also Kevin J. Hayes, George Washington: A Life in Books(New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[5]George Washington, Washington Papers, Series 1, Exercise Books, Forms of Writing, www.loc.gov/item/mgw1a.001/.

[7]George Washington, “Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation,” Manuscript, The Washington Papers, washingtonpapers.org/documents_gw/civility/civil_01.html.

[8]John Marshall, The Life of George Washington, 5 vols. (1804; reis., Philadelphia: J. Crissy, 1838), 1:3.

[9]Mason Weems, A History of the Life and Death, Virtue and Exploits of General George Washington, ed. Mark Van Doren (1808; reis., New York: Macy-Masius, 1927), 5.

[10]Jared Sparks, The Life of GeorgeWashington(Boston: Tappen and Dennet, 1842), 6, 513.

[11]Washington Irving, Life of George Washington, 5 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam & Company, 1855-59), 1:54.

[12]J. M. Toner, ed., Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation: A Paper Found Among the Early Writings of George Washington: Copied from the Original with Literal Exactness, and Edited with Notes (Washington, D.C. W.H. Morrison, 1888), 5-9.

[13]Paul Leicester Ford, The True George Washington(Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896), 74.

[14]For a recent survey of Moncure D. Conway, see Dwayne Eutsey, “Devil-Lore and Avatars: Moncure Conway’s Likely Influence on ‘No. 44, the Mysterious Stranger,’” Mark Twain Journal 54, no. 1 (2016): 95-115.

[15]Moncure D. Conway, ed., George Washington’s Rules of Civility Traced to their Sources and Restored (New York: United States Book Company, 1890), 10-12.

[16]I am indebted to my colleague Keith Kesten of the Foreign Languages Department at Cinnaminson High School, New Jersey, for providing this translation.

[17]Conway, Washington’s Rules, 12-14.

[18]Francis Hawkins, Youth’s Behavior, or Decency in Conversation Amongst Men, rev. ed. (London: W. Wilson, 1646).

[19]Conway, Washington’s Rules, 20.

[22]Charles Moore, ed., George Washington’s Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926).

[24]John Ferling, The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009), 11.

[25]Joseph Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington(New York: Alfred Knopf, 204), 9.

[26]Peter R. Henriques, Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington(Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 182; Peter R. Henriques, First and Always:A New Portrait of George Washington(Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2020), this book makes no mention of Washington’s “Rules of Civility.”

[27]Gordon S. Wood, “The Greatness of George Washington,” in Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different(New York: Penguin Books, 2006), 36.

[28]Gordon S. Wood, “The Founders and the Enlightenment,” in ibid., 11-15.

[29]Francis Hawkins, Youth’s Behavior, or Decency in Conversation Amongst Men,rev. ed. (London: W. Wilson, 1663).

[30]Moore, Washington’s Rules of Civility.

[31]For example, Washington’s Rule 5 combines Hawkins’s Chapter 1, numbers 8 and 9; Rule 8 combines chapter 1, numbers 15 and 16; Rule 11 combines Chapter 1, numbers 19 and 20; Rule 87 combines chapter 6, numbers 35 and 39; Rule 92 combines chapter 7, numbers 2, 3, 4, and 7. See Moore’s helpful compilation of both the Washington and Hawkins works in Moore, Washington’s Rules of Civility.

[32]There is but a single exception to this claim; Washington’s thirty-second rule contains several more words than Hawkins’ chapter two, maxim ten. Other than this outlier, Washington’s maxims are shorter and more direct than the seventeenth-century English translation. See Moore, Washington’s Rules of Civility, 38.

[33]Moore, Washington’s Rules of Civility, 27, 35, 36, 37.

[34]For James Mayre’s native tongue and Jesuit education in France, see “Washington Guided By Jesuit Rules,” American Catholic Historical Researches 21, no. 4 (1904): 151-53.

[35]Conway, Washington’s Rules, 45, 46.

[36]Toner,Rules of Civility, 9.

[37]Stefan Ehrenpreis, “Reformed Education in Early Modern Europe: A Survey,” Dutch Review of Church History 85 (2005): 39-51; Lowell C. Green, “The Bible in Sixteenth-Century Humanist Education,” Studies in the Renaissance 19, (1972): 112-134; Sheldon Rothblatt, Tradition and Change in English Liberal Education: An Essay in History and Culture (London: Faber and Faber, 1976); Wood, “The Founders and the Enlightenment,” in Revolutionary Characters, 11-15.

[38]Baldesar Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, trans. Leonard Eckstein Opdycke (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902).

[39]T. Pape, “Appleby Grammar School and Its Washington Pupils,” William and Mary Quarterly 20, no. 4 (1940): 498-501.

[40]Peter R. Henriques, Major Lawrence Washington versus the Reverend Charles Green: A Case Study of the Squire and Parson,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography100, no. 2 (1992): 233-64; Pape, “Appleby Grammar School,” 498-501.

[41]Jonathan Boucher, Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 1738-1789, Being the Autobiography of the Revd. Jonathan Boucher, Rector of Annapolis in Maryland and afterward Vicar of Epsom, Surrey, England (1797; reis., Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925), 49.

[42]Ford, True Washington, 65.

[43]George Washington, The Journal of Major George Washington (Williamsburg: William Hunter, 1754), 2.

[44]Timothy Pickering as quoted in Ford,True Washington, 66; George Washington to David Humphreys, July 25, 1785, in W.W. Abbot, et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington: Confederation Period, 6 vols., (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1992-), 2:148-51.

[45]Washington to Joseph Reed, January 23, 1776, in Philander D. Chase, et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Series, 28 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985-), 3:172-75.

[46]John Adams to Benjamin Rush, April 22, 1812, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5777.

[47]Humphreys to Washington, January 15, 1785, in W.W. Abbot, et al., Papers of Washington, 2:268-69.

[48]Washington to Humphreys, July 25, 1785, in Ibid., 2:148-51.

[49]David Humphreys, Life of Washington with George Washington’s Remarks, ed. Rosemarie Zagarri (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991). Humphreys actually did not publish his work though he allowed part of it to be printed in Jedidiah Morse’s American Geographyin 1789. The manuscript vanished until its 1960s discovery by historian James Thomas Flexner.

[50]Humphreys, Life of Washington, 6.

[51]Washington to Humphreys, July 25, 1785, in Abbot, et al., Papers of Washington, 2:148-51

[52]Washington to William Ramsey, January 29, 1769 in Ibid., 8:167-68.

[53]Washington to Jonathan Boucher, January 2, 1771 in Ibid., 8:425-26.

[54]Washington to William Smith, August 18, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-09173.

[55]“Act Giving Canal Company Shares to General Washington,” January 4-5, 1785, in William T. Hutchinson, et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison: Confederation Period, 17 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962-91), 8: 215-16; Betty Ruth Kondayan, “The Library of Liberty Hall Academy,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 86, no. 4 (1978): 432-46; James T. Flexner, George Washington and the New Nation, 1783-1793(Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970).

[56]“First Annual Message to Congress,” Gazette of the United States, January 9, 1790.

[57]“The Tablet,” Gazette of the United States, January 30, 1790.

[58]George Washington to the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, December 7, 1797, in Dorothy Twohig, et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series, 21 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987-2020) 21:317-35.

[59]George Washington, “Farewell Address,” in Philadelphia Daily American Advertiser, September 19, 1796; For a careful study of the drafts of the address as well as the mystery of authorship, see Jeffrey J. Malanson, “If I Had It in His Hand-Writing I Would Burn It”: Federalists and the Authorship Controversy Over George Washington’s Farewell Address, 1808-1859” Journal of the Early Republic34, no. 2 (2014): 219-42.

[60]Boucher, Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 49.

[61]Adams to Rush, August 23, 1805, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5096.

[62]Thomas Jefferson to Walter Jones, January 2, 1814, in J. Jefferson Looney, et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, 17 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004-20), 7:100-4.

[63]Adams to Rush, April 22, 1812, January 5, 2023, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5777.

3 Comments

Shawn, thank you for a very insightful and interesting article.

Thank you for an interesting article. I heard about Washington’s Rules of Civility from my father when I was a child. To my father, whose own father died in 1925 when he was nine, it was obvious why Washington copied out his Rules. George’s father had died when he was nine. Dad believed George was committing to memory the sort of parental advice on gentlemanly behavior that he would have otherwise received. My father read Washington’s Rules of Civility for the same reason.

Sorry, Washington’s father died when George was eleven. Typed too quickly!