On October 10, 1774, the brigantine Charlotte arrived at Newport, Rhode Island, from London. On board was a sailor named Samuel Dyer, and he told a shocking story, soon reported in the local newspapers. Three months earlier, on July 6, soldiers of the 4th or King’s Own Regiment had grabbed him off the streets of Boston and kept him “confin’d in irons” in their camp.[1] And that was just the start of his harrowing tale.

According to Samuel Dyer, the 4th Regiment’s commander, Lt.-Col. George Maddison, had asked Dyer “who gave him orders to destroy the Tea” tossed into the harbor the previous December. Dyer insisted no one had told him to do that. Maddison replied, “he was a lyar, it was King Hancock, and the damn’d Sons of Liberty”! The officer told Dyer that “he should be hung like a dog” in London, and advised him “to prepare a good story” for the royal governor, Gen. Thomas Gage. Then the sailor, still in chains, was loaded onto Adm. John Montagu’s flagship, the Captain, to await Gage.

But the governor never came, Dyer said. Instead, after three or four days the ship sailed out of Boston harbor, taking Montagu home. Once the Captain arrived in Portsmouth, in the south of England, Dyer “was sent up to London in irons, and examined three times before Lord North, Sandwich, and the Earl of Dartmouth, respecting the destruction of the Tea.” The men he named were the British Prime Minister, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and the Secretary of State in charge of North America—three of the most powerful officials in the imperial government. Since Dyer still had nothing to say about the Tea Party, however, they sent him back to Portsmouth, still chained up.

And then, Dyer’s complaint continued, the Royal Navy simply set him free as if he were an ordinary sailor, but “without receiving one farthing of wages.” Dissatisfied, the seaman “travell’d up to London, 70 miles, (having but six coppers in his Pocket) and made his complaint to the Lord Mayor,” Frederick Bull. The city government, dominated by merchants concerned in the colonial trade, was often at odds with the imperial government, and the Lord Mayor greeted Dyer “with great Humanity.” Other men, Dyer said, offered him “purses of guineas” if he would “accuse certain gentlemen in Boston with ordering him to help to destroy the tea,” but he remained adamant.

Dyer received the most support from two London sheriffs, William Lee and Stephen Sayre. Those men were Americans—Lee born in Virginia and Sayre in New York. They promised Dyer that they “and many other gentlemen” would “supply him with any sum of money to carry on a suit against those governmental Kidnappers in Boston,” assuming he could “prove his charge.” A later American newspaper report said those sheriffs had “generously supplied him with Money, and procured him a Passage” home.[2] When he arrived in Rhode Island, the sailor brought sealed letters from William Lee addressed to the Massachusetts political leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

Among the Patriots in Newport was Dr. Thomas Young. From 1768 on, he had been one of the most prominent protest leaders in Boston, able to lead large crowds despite also being known for his unorthodox ideas on democracy and deism. Young had first come to the royal authorities’ attention by supporting people trying to keep British troops out of the government-owned Manufactory building. Just before the Boston Massacre in 1770, the doctor was out on the streets, and a year later he returned to the Manufactory to deliver the first oration commemorating that Massacre. During the Boston Tea Party, Young delivered another speech about the bad medical effects of tea—probably a ploy to keep the audience inside the Old South Meeting House, providing alibis for almost all the Whig leaders, while other men got to work destroying the East India Company’s cargo without interference. In the spring of 1774 British regiments returned to Boston. Dr. Young and his wife feared he might be attacked or arrested, so in September the family had suddenly left for Rhode Island.

On October 10, Doctor Young heard the “prodigious noise” kicked up by Samuel Dyer’s story. He hurried to the office of Rhode Island Secretary Henry Ward to learn more. There he spotted Dyer and “instantly knew” him. Back in Boston, Young had a habit of getting into vituperative newspaper arguments not only about politics but also about religion and medicine. Even his political ally Dr. Joseph Warren had complained of enthusiastic “youngism.”[3] In 1767 Young’s public dispute with a rival doctor named Miles Whitworth became so heated that Whitworth’s teenaged son had slapped Young around on the street. When in the middle of 1773 two other men attacked Young one night, he still blamed Whitworth, rightly or not. But on that occasion, Young recalled, there had been a “sailor who rescued me out of the hands of Whitworth’s mob”: Samuel Dyer.[4]

Doctor Young told his Newport friends that he could vouch for this new arrival. Some of those gentlemen were still dubious about the connection, so to satisfy them Young walked by Dyer on the street. The sailor recognized the doctor “at first sight.” Young then had this exchange with Dyer, as he described to Samuel Adams:

He told me he had letters from Mr. Sheriff Lee to yourself and Mr. Hancock, which on going into Mr. Southwick’s office he shewed me, and I knew the handwriting. I told him you were absent at the [First Continental] Congress at Philadelphia, and desired the Letter to transmit to you there. He returned that Sheriff Lee had enjoined him to carry both letters to Boston, and in case of the death or absence of either of you to deliver the letters to the present gentlemen and in case both were dead to burn them unopened or never come to him again. In this dilemma I took your letter home to my house & carefully cut the cover preserving the seal and having transcribed the deposition and perused the attending letter closed them up and in another cover committed them to him again, informing him however of the freedom I had taken with them and entering my apology for it within the covers.

Always enthusiastic and unbound by convention, Young saw no problem in breaking open the envelope that Dyer was supposed to protect so carefully.

The Rev. Ezra Stiles of Newport was often a sucker for wild rumors and false claims that fit his political thinking. But he used some uncharacteristically skeptical language in describing Dyer’s story: “If it should appear to be a real Seizure of an American & carrying him home in Irons for a Trial, it will rouse the Continent—if he was in fact carried to London in Irons and examined by any of the Ministry, as he says.”[5] The minister looked for reasons to believe Dyer. He wrote, “About the time he was taken there was an account in the Boston prints of a Man of his Name missing & supposed to have been drowned.” In fact, while the July 4 Boston Evening-Post had reported about a body found floating in Boston harbor, no newspaper had identified that man as Samuel Dyer or said Dyer was missing.[6] Stiles, not for the first time, ended up selecting his facts to fit his convictions.

The minister also recalled hearing reports that an army officer passing through Newport to New York had “seemingly accidentally mixt in with some of the Mechanics & robust Tradesmen warm for Liberty, & said in their Hearing that one of the Rebels was lately taken at Boston & sent home in Irons.” Young wrote that he had heard the same whispers:

his being kidnapped is confirmed by the information of two officers given here at sundry times, presently after the affair. One of them was so circumstantial as to mention his being confined in the common and then being put on board the Captain, where he saw him in irons. This was said in a barber’s shop, where many now remember they heard it.

If these memories were accurate, these army officers were trying to make Dyer’s fate into a warning for other workingmen “warm for Liberty.”[7]

Unfortunately, Samuel Dyer himself is a mystery. His own statements and others’ say that he was from Boston and had a wife and children there, but no one mentioned his age or those relatives’ names. As an ordinary sailor, he was very unlikely to own property, advertise in newspapers, or formally join a church. And the name Samuel Dyer was relatively common. In the 1770s there was a Boston office-holder named Samuel Dyer, and a Newport merchant. (The latter spelled his last name “Dyre,” and the Rhode Island newspapers sometimes rendered the sailor’s surname the same way.) Further afield, the radical British politician John Wilkes had a valet named Samuel Dyer a few years before.[8] Doctor Young’s recollection about the fight in Boston is the only solid clue to this Samuel Dyer’s activity before the fall of 1774.

On October 11, the Newport committee of correspondence examined Dyer. He swore to an affidavit about his horrendous experience. The Rhode Islanders decided to send the sailor on to Massachusetts with their endorsement, as well as ten or twelve dollars for his expenses—a “genteel viaticum,” wrote Young, who rarely ended letters without tossing in some classical phrases and allusions to demonstrate how well he had educated himself.

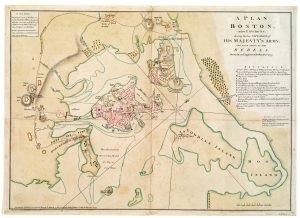

In sending Samuel Dyer back to Boston, the Newport Patriots risked striking a spark inside a powder house. In late summer Parliament’s Massachusetts Government Act, coming on the heels of the Boston Port Bill, had pushed the province into turmoil. Crowds were forcing the county courts not to open, starting in the western counties. On September 2, a militia uprising culminated in thousands of men ringing Lt. Gov. Thomas Oliver’s house in Cambridge and forcing him to sign a resignation. General Gage had responded by mounting cannon on Boston Neck, pointing out at the people he was supposed to govern. With British regiments stationed in Boston, and more being summoned from other parts of the continent by Gage, that town became a refuge for royal appointees who no longer felt safe in their home towns. But most locals seethed about the military occupation. Among other covert acts, they spirited away their militia’s four cannon before the Royal Artillery could confiscate them.[9]

Outside Boston, Patriots felt safe enough to convene a Massachusetts Provincial Congress in direct defiance of Parliament’s new law. This was the equivalent of the lower house of the colony’s regular legislature, which Gage had refused to meet with. These elected delegates first gathered on October 7 in Salem, choosing John Hancock to preside over their sessions. On October 11–14, the body convened in Concord. Those days were taken up in getting organized, writing a critical report on the state of the province, and calling on towns not to send tax revenues to the royal government’s treasurer. Then the men agreed to meet in Cambridge on October 17.

Samuel Dyer reportedly planned to travel from Newport to Concord to deliver his letter to John Hancock. It is not clear if the sailor reached that town before the Provincial Congress adjourned on the afternoon of Friday, October 14. In any event, Dyer’s main business lay in Boston. Stiles wrote that the sailor planned to “take Evidences & return to London, where he intends to eat his Xmas Dinner.”[10] Young agreed that “a prosecution may be carried on against those dignified scoundrels to the satisfaction of the immediate sufferer and advantage of the public.”[11]

Dyer was in Boston by Sunday, October 16. On that day, the Patriot publisher Joseph Greenleaf wrote to his brother-in-law Robert Treat Paine, then at the Congress in Philadelphia, about the sailor’s story. According to Greenleaf, General Gage had promised Dyer “that there shall be an examination of the affair” the next day.[12] The Patriot-leaning merchant John Andrews wrote that the sailor’s story of being kidnapped was widely believed and causing “much speculation” in Boston.[13] Nonetheless, he cast some blame on Dyer himself for his trouble: “he having said that he knew all about and who were concern’d in the destruction of tea—being an artfull fellow and one who pretends to know every thing—in consequence of which, he was seiz’d by two soldiers.”

On October 17, Andrews reported hearing that John Hancock and Lieutenant Colonel Maddison “had an interview” about the sailor’s allegation that the colonel had tried to make him accuse “King Hancock” of being behind the Tea Party. Andrew heard that “the latter has fully satisfied the former that what the fellow has alledged is absolutely false.” General Gage might have hoped that the agreement between those gentlemen would lay the whole affair to rest.

Dyer himself clearly was not satisfied. He had reportedly come to Boston to “take Evidences” and start a “prosecution” against Lieutenant Colonel Maddison. But he could not file a lawsuit for damages because the Patriots had shut down all the provincial courts as a protest against Parliament’s Massachusetts Government Act. According to Andrews, Dyer “declar’d since he came home, that if he could not have public satisfaction for his extraordinarytreatment, he would take it personally.”[14] The aggrieved sailor decided to act on his own.

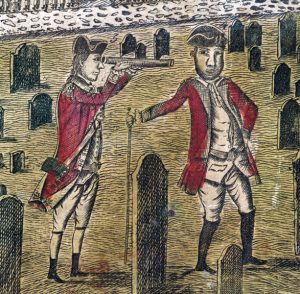

About noon on Tuesday, October 18, Dyer spotted two British army officers “returning together from the Neck” at the southern tip of Boston, where General Gage had ordered new fortifications and artillery.[15] Those military men were Lt. Col. Samuel Cleaveland, the head of the Royal Artillery in North America, and the army’s chief engineer, Capt. John Montresor. Cleaveland was around age fifty-eight, no longer young but spry enough to take one of the twentysomething daughters of the South Latin School’s master as his mistress.[16] At thirty-eight, Montresor had served in America for years. As for mistresses, Montresor had had at least three in America and would inspire the roué who seduced the title character in Charlotte Temple, America’s first best-selling novel.[17] These two officers “were standing together in the main Street, just above Liberty tree.”

Dyer came up and asked Capt. Montresor “if his name was Collonel Maddison.” Montresor’s Royal Engineers uniform in bright red cloth with blue facings was similar to the coats of officers in the 4th Regiment. However, given that the sailor had repeatedly and loudly identified Maddison as the officer who had interrogated him at length three months before, he should have been able to recognize that man.

The two officers had reason to be wary about strangers. According to Lt. Ashton Shuttleworth of the artillery, a local had “cut a running Centry on his Post with a Cutlass in the middle of the day, and cut one of his Ears off,” and Bostonians would “get in Bodys about the Dusk of the Evenings, and whenever they get one or two Officers by themselves, they will abuse and knock them down, if they can.”[18] But this encounter was taking place at midday on the town’s busiest street, so Cleaveland and Montresor did not have their guard up. They told Dyer that neither of them was Maddison and sent him on his way.

The sailor did not accept that answer. He snuck up on Cleaveland’s left side, snatched his sword from its scabbard, and “made a back Stroke with it” at the officer’s head. Cleaveland ducked. Dyer “drew out a Pistol and directed it at the Colonel, but it missed Fire.” Captain Montresor pulled out “a Kind of half Dirk” and moved toward Dyer. The sailor pulled out another pistol and pointed it at the engineer’s head “at about three Yards Distance.” But that gun “flashed in the Pan.” Montresor ducked behind a cart.

Doubly frustrated, Dyer turned back to Colonel Cleaveland and “made two or three Strokes at him” with his own sword.

The Colonel elevated his arm, and fortunately received the blow upon one of his buttons on the sleve of his coat, which diverted the edge in such a manner, as that the blade glanced down by the side of his head and gave him only a small wound in the neck, and splitt the favorable button in two.

Still, those swipes cut through the colonel’s hat and “made an Incision behind his Ear.” As Dyer went in for another thrust, “a Townsman jump’d in between, and near got his Arm quite cut off.”

The sailor decided he had made his point. He ran south down Orange Street to the gates of Boston. One source said he threw his pistols at Montresor, another that he tossed them “into a Shop as he went along.” Either way, Captain Montresor picked up those guns while Dyer kept Colonel Cleaveland’s sword. Up to three hundred men were reportedly at work nearby, but no one tried to stop the sailor. He passed through the gates of Boston, “even walked by the Guard with the Hanger drawn in his hand.” Dyer was not simply escaping—he was seeking a sympathetic audience.

From the narrow Boston Neck, Dyer headed south through Roxbury and then turned onto the road to the first bridge across the Charles River. That route led straight into Cambridge. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress had convened in that town’s Congregationalist meetinghouse the previous day. That body was continuing its high-level epistolary exchange with the royal governor about who was doing more to undermine Massachusetts’s charter. Since uncharitable observers might consider that debate as treasonous, that morning the delegates had voted “That the galleries be now cleared, and that the doors of the house be kept shut, during the debates of the Congress.”[19] The Cambridge delegates recruited a local man to be doorkeeper.

Dyer apparently refused to be excluded. According to Andrews, the sailor “went into the room where the provisional Congress were sitting” and showed them Cleaveland’s hanger, possibly colored with a bit of Cleaveland’s blood.[20] He told the representatives “he had got one of the swords that Lord North had sent over to kill ’em with.” Again, it is not clear whether any of those men had already met Dyer in Concord or Boston. John Hancock was presiding over the meeting; he had evidently heard about the seaman’s accusations but may not have met him personally. In any event, the sailor’s surprise arrival with a stolen sword surely made a big impression.

But that was not an impression that the Provincial Congress wanted to be part of. The Massachusetts Patriots were trying to portray themselves as aggrieved victims, protesting respectably against the imperial government’s oppression and forced to convene this outlawed legislature by that government’s intransigence. They painted that self-portrait in words to their neighbors, to the representatives of other colonies at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and to sympathetic Whigs in London. Despite all the violence in Boston during the previous ten years, no townsman had yet fired a gun at a royal official or soldier. (As the Patriots were happy to remind people, back in 1770 the Crown’s customs officers and soldiers had fatally shot four men and two boys.) An angry sailor snapping pistols at army officers in the street threatened to sully the whole Patriot movement.

Dyer’s attempt on the two British officers might even have set off a harsh government crackdown or ignited a war. He had, after all, traveled to Boston with the support, and perhaps the money, of the imperial government’s opponents in two other cities, and had been greeted with some enthusiasm by the Patriots there. If he had actually taken one or two officers’ lives, the royal government would have had to act against him. The Massachusetts Patriots might have feared that, if they did not repudiate Dyer, General Gage would use his action as an excuse for military intervention. Though the Provincial Congress was already discussing the possibility of war against the king’s forces, they knew they were not ready for it; they were still forming committees to decide what further committees they needed to form.

The Patriots in Cambridge therefore concluded that Dyer was dangerous. “When they came to know what he had been doing,” Andrews wrote, “they immediately sent for an officer and committed him.”[21] Nothing about this disruption went into the congress’s official record. The next day, wrote merchant John Rowe, the sailor “was brought from Cambridge & committed to our Goal,” or jail, in the center of Boston. Rowe deemed Dyer “an audacious Villain.”[22] Boston’s Patriot newspapers all reported the attempted shooting in one short paragraph, two stating early that Dyer “appears disordered in his senses” and the third concluding, “It is in general imagined that he is insane.”[23] The Boston Post-Boy, leaning firmly toward the royal government, carried the most detailed report on the violence. With the court system shut down, the angry sailor would stay in the Boston jail indefinitely. Samuel Dyer’s attack on British army officers had not made him a hero, and only by a stroke of luck had he not started a larger conflict.

Despite the congress’s repudiation, army officers took Dyer to be typical of the New England resistance, probably even directed by its leaders. Capt. William Evelyn of the 4th Regiment wrote home that the sailor was one of “their agents,” not just a madman acting on his own.[24] Later Captain Montresor would perceive a wider conspiracy: “This man was sent off by the Sheriffs of London, Messrs. Lee and Sayre, to murther Lt.-Col. Maddison of the 4th. Regiment.”[25] Dyer’s misfiring pistols had prevented his attack from being fatal, but it still raised tensions. The Patriots might repudiate the angry sailor’s actions, and even start to doubt his story of being hauled off to London in the first place, but they still had to deal with how his action had made all of General Gage’s defensive actions seem more reasonable.

Meanwhile, in his official residence at the Province House, Gage was secretly dealing with his own Samuel Dyer headache. Because he knew that many of the sailor’s wild accusations about royal officials were actually based in fact.

[1]“confin’d in irons”: This text from the Essex Gazette, October 25, 1774.

[2]“generously supplied him”: Boston Post-Boy, October 24, 1774.

[3]“youngism”: Boston Gazette, July 6, 1767. For a thorough analysis of this debate, see Samuel A. Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill, and the Birth of American Liberty (Baton Rouge: Pelican, 2011), 70–87.

[4]“sailor who rescued me”: Young to Samuel Adams, October 11, 1774, Samuel Adams Papers, New York Public Library (NYPL).

[5]“If it should appear”: Ezra Stiles, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, D.D., Ll.D., Franklin Bowditch Dexter, editor (New York: Scribner’s, 1901), 1:462-3.

[6]Drowned men: The Evening-Postsaid of the drowned man, “by some Articles found in his Pockets, it is supposed that he was a Taylor; But as his Face was greatly disfigured, . . . the Jury was obliged to give a Verdict, that he was a Person unknown, and drowned by Accident.” Boston Evening-Post, July 4, 1774. The Essex Gazettehad also reported a drowned man that summer up in Marblehead harbor, someone whose shoe buckles bore the initials “B G”; Essex Gazette, June 28, 1774.

[7]“his being kidnapped”: Young to Adams, October 11, 1774, Samuel Adams Papers, NYPL.

[8]Wilkes’s valet: Arthur H. Cash, John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 218, 273.

[9]“their militia regiment’s cannon”: For the full story, see The Road to Concord: How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016).

[10]“take Evidences”: Stiles, Literary Diary, 1:462–3.

[11]“a prosecution”: Young to Adams, October 11, 1774, Samuel Adams Papers, NYPL.

[12]“that there shall be an examination”: Greenleaf to Paine, October 16, 1774, Papers of Robert Treat Paine, Stephen T. Riley and Edward W. Hanson, editors (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2005), 3:11.

[13]“much speculation”: Andrews, October 17, 1774, Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings (MHSP), 8:377.

[14]“declar’d since he came home”: Andrews, October 18, 1774, MHSP, 8:377.

[15]Dyer’s attack: This account is based on reports in the Boston Post-Boy, October 24, 1774; Lt. Ashton Shuttleworth to John Spencer, November 2, 1774, in “Letters by British Officers from Boston in 1774 and 1775 to John Spencer,” Bostonian Society Proceedings, 38 (1919), 12–3; and Andrews, October 18, 1774, MHSP, 8:377–8. Those three accounts do not agree completely on the sequence and details of the action.

[16]Samuel Cleaveland: Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, 4th edition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1873), 140. Francis Duncan, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery (London: John Murray, 1879), 1:297–318.

[17]John Montresor: “The Montresor Journals,” G. D. Scull, editor, Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 14 (1881). For his fictionalization in Charlotte Temple, see Philip Young, Revolutionary Ladies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), 24–6.

[18]“cut a running Centry”: Shuttleworth to John Spencer, November 2, 1774, Bostonian Society Proceedings, 38:12–3.

[19]“That the galleries be now cleared”: Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, William Lincoln, editor (Boston: Dutton & Wentworth, 1838), 22.

[20]“went into the room”: Andrews, October 18, 1774, MHSP, 8:378.

[21]“When they came to know”: Andrews, October 18, 1774, MHSP, 8:378.

[22]“an audacious Villain”: John Rowe diary, October 19, 1774, 11:1918, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[23]“appears disordered”: Massachusetts Spy, October 20, 1774; Boston Gazette, October 24, 1774; and Boston Evening-Post, October 24, 1774.

[24]“their agents”: William Glanville Evelyn, Memoir and Letters of Capt. W. Glanville Evelyn, of the 4th Regiment (“King’s Own”) from North America, 1774-1776,G. D. Scull, editor (Oxford: James Parker, 1879), 35.

[25]“This man was sent off”: “Montresor Journals,” Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 14:120.

2 Comments

I read this and thought “This is a good story” and only at the end did I see the author. Of course it’s a good story. J. L. Bell is the best author available on the subject.

Thank you kindly!