Between heroes like George Washington and villains like Benedict Arnold, the Revolutionary War was full of historical actors of all stripes. But one man in particular defies an easy sorting between hero and villain. Washington’s first adjutant general, Horatio Gates, does not have a secure place in historical memory as either hero or villain. In the beginning of the war, Gates was Washington’s right-hand man and a successful army administrator. Subsequently Gates achieved the war’s most decisive early victory at Saratoga on October 17, 1777, considered to be the war’s turning point for securing the French alliance. Unfortunately, Gates’ life did not finish on such a high note. Despite these early achievements, Gates is often remembered as a lackluster officer, a potential betrayer of Washington, and an ultimate failure after the Battle of Camden.[1] Such a detrimental assessment may be surprising given his victory at Saratoga that did so much to save the American cause. Truthfully, Gates was a highly ambitious man. In his lifetime, his aspirations for fame and success led him to become both a success and a failure. Therefore, Gates presents a conundrum for historians. Who was this man, and where should he land in the war’s historical memory?

Early Career

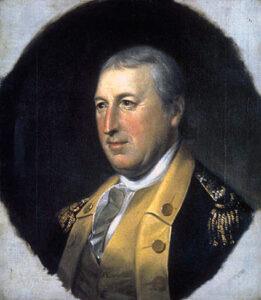

Born in England in 1728, Gates came from a relatively humble social background. He sought a career in the British army, and at age twenty-one he was fortunate enough to gain a commission as a lieutenant under Gen. Edward Cornwallis (the uncle of the more famous Charles Cornwallis), and Gates served in Nova Scotia for several years.[2] He performed well enough that by 1754, on the eve of the French and Indian War, he became a captain in the 4th Independent Company of Foot in New York.[3] He arrived just in time to serve in the war that would boost his fortunes and ambitions higher than he likely anticipated.

Gates’ career took off during the French and Indian War with a wave of success. He served throughout the war and even met George Washington. The two served together in the Braddock expedition and fought at the Battle of Monongahela, where Gates suffered a wound in combat.[4] The remainder of the war was kinder to him, and he tied his fortunes to Brig. Gen. Robert Monckton. Gates served on Monckton’s staff where he performed well enough to gain Monckton’s favor. After winning a decisive victory against the French in Martinique, General Monckton personally asked Gates to deliver the news of the victory back to England along with a praising letter of recommendation; this act resulted in Gates receiving a commission as a major in the British army, which was no small feat.[5] Given Gates’ humble origins in England, this promotion was a significant life event that likely primed him with thoughts of pursuing a future military career to achieve a greater station in life.

Gates’ ambitions and good fortune from the French and Indian War hit a road block following the war’s conclusion in 1763. After the war, the British army reduced in size, and valuable positions and promotions became scarce. Despite holding a major’s commission, Gates was unable to find a suitable position to fill in the British army and soon found himself facing financial difficulties. After years of failed political maneuvering and favor seeking, Gates sold his commission and left England. In 1773, he sailed with his wife to America and bought land in Virginia, which became his new home named Traveler’s Rest.[6]

Right-Hand Man

Gates would not have to wait long to end his civilian life and rejoin the military world. As a man with British military experience and well-known political views in favor of American independence, the Continental Congress easily considered him for service in the new Continental army. At the very beginning of the American Revolution, Congress appointed him as George Washington’s adjutant general on June 17, 1775. He arrived in Washington’s headquarters on July 9, and quickly got to work.

Gates performed admirably as the Continental army’s first adjutant general. While the adjutant general in today’s army is mostly associated with personnel administration, during the Revolutionary War the adjutant was the “right hand of the commander” with broader responsibilities including publishing orders, unit discipline, training, intelligence, and even sanitation.[7] Gates relieved Washington of many duties, including publishing the Articles of War and issuing instructions to the recruiting service.[8] Gates completed the army’s first strength return on July 19, 1775.[9] Evidently, he was up to the task and excelled as Washington’s adjutant.

Gates shared in the Continental army’s early successes and his star continued to rise. After a turbulent year, the army achieved its first major victory when the British evacuated Boston in early 1776. Gates was heavily involved in achieving this victory, so much so that Washington recommended him for promotion.[10]Congress promoted Gates to major general in May 1776 and he soon left Washington’s staff. Losing Gates was painful to Washington, who went as far as to ask him to return to his former post, writing: “I look upon your resumption of the Office of Adjutant General as the only means of giving form and regularity to our new Army.”[11]Not to be tied down as Washington’s subordinate, Gates pursued dreams of grandeur. After much political maneuvering, letter writing, and favor trading, the ambitious Gates soon landed himself a new job as commander of the army’s Northern Department, where he would reach his greatest achievement.[12]

Hero of the Revolution

Successful in his role as adjutant general and well connected with the Continental Congress, Gates became the Northern Department’s commander on August 19, 1776.[13] Gates inherited an army that he described in a “deplorable state to which death, defeat, desertion, and disease had most unhappily reduced.”[14] Gates used his expertise in administration and organization to turn affairs around. His troops liked him, and in one scholar’s words Gates “electrified” morale, giving it a much-needed boost.[15] The following year, the Northern army began sparring with British Gen. John Burgoyne’s army then invading New York. Gates successfully halted a British advance at the Battle of Freeman’s Farm in September 1777.[16] Following the victory, disputes between Gates and his key subordinate, Gen. Benedict Arnold, erupted over the appropriate next steps, as well as credit for the victory.[17] The two generals argued endlessly, and Gates ultimately relieved Arnold of his command.

Following the altercation with Arnold, Gates soon achieved the greatest success of his life. Although he preferred a defensive strategy, his subordinates (including Arnold, despite having been relieved of his position) led the Continentals into offensive action that resulted in another decisive victory at Bemis Heights.[18] General Burgoyne, now on the backfoot, began retreating and negotiating for a treaty with Gates. On October 17, 1777, Gates accepted Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, considered by historians to be the turning point of the American Revolution. The victory led to France declaring war on Britain and becoming America’s vital ally that enabled the American Revolution’s ultimate success. For this action, Congress presented Gates with a gold medal made in his honor. Gates’ actions at Saratoga were absolutely vital to the American Revolution’s success. Although he didn’t know it at the time, Gates, now standing at the summit of his lifetime achievement, was about to take a perilous fall to the bottom.

From Hero to . . . Less than Heroic

Whereas Gates accomplished America’s greatest victory to date in 1777, George Washington met crushing defeats at Brandywine and Germantown and now found his Army suffering in the long winter at Valley Forge. This difference in short-term achievement led to a permanent rupture in the two’s relationship and the first of many scandals in Gates’ career. For instance, Gates had not even bothered to inform Washington of his victory at Saratoga, leaving Washington to learn about it second-hand.[19] Soon thereafter, rumors that George Washington was an unfit commander in chief surfaced in the infamous Conway Cabal. The gossip’s author, Gen. Thomas Conway, suggested that Gates would be a better commander than Washington, and speculation circulated amongst several officers and congressional delegates.[20] Washington was outraged, writing “that General Gates was to be exalted, on the ruin of my reputation and influence” and further called Conway a “malignant partisan.”[21] The full extent of Gates’ role was murky, but he nonetheless appeared happy to reap the benefits of any potential promotions if Congress saw fit to remove Washington.[22] Ultimately, by April 1778 the “cabal” amounted to nothing and General Conway resigned. The lasting impact of the affair was to permanently sever an already strained relationship between Gates and Washington, one that would never recover.

Following his success as the Northern Department’s commander, Gates gained more favor and attention from the Continental Congress, and the ever-ambitious officer began seeking his next triumph. Gates landed himself a variety of new positions and commands, but none of them seemed to fit his ego. In November 1777 he became the chairman of the Board of War which was to become the link between Congress and field commanders.[23] However, the Board of War was notoriously inefficient, and its efforts amounted to little more than running estimates, submitting requests, and navigating a bloated bureaucracy where fraud and corruption were common.[24] Seeking a more enviable post, Gates soon returned to command the Northern Department, only now it was no longer an independent command (Washington was close enough nearby that he maintained command of it) and Gates was subordinated to Washington, who at this time had a hostile opinion of Gates. In arguing over a proper role for himself, Gates found himself bouncing around from post to post, including being the commander of the upper Hudson (where he planned an invasion of Canada that never manifested), commander of Boston for a brief period, and lastly commander of Providence, Rhode Island.[25] In all of these jobs, Gates found little action or fulfillment for his aspirations. A dissatisfied Gates asked for a respite from service, and with Washington’s approval, he took a leave of absence in early 1780 at his home in Traveler’s Rest.[26]

Gates would not have to wait long for another chance at glory, but unfortunately it would also be the greatest disaster of his life. In June 1780 Congress appointed Gates commander of the independent Southern Department which was in a state of disarray after fighting a losing campaign. Upon assuming command, Gates complained that his “distress has been inconceivable,” with the Southern army suffering from a lack of food, clothing, and basic supplies.[27] Despite his army’s shortcomings, Gates ordered a direct offensive towards the British that culminated at the battle of Camden, South Carolina.[28]

On the road to Camden, Gates made a series of foolish decisions that can only be explained by his own blind ambition to achieve a decisive victory. While his subordinate officers advised Gates to take an alternative and safer route, Gates pursued the most direct route possible to the British position and promised “rum and rations” along the way (which were never provided).[29] Gates mistakenly believed he commanded over 7,000 soldiers, and upon learning (from his adjutant no less) that he only possessed about 3,000, he maintained his predetermined course of action despite lacking sufficient intelligence of his enemy’s position and strength. Gates’ army was surprised when it blundered into the British army the morning of August 16. Evidently, Gates gave only one single order during the battle in which he commanded his militia forces to make a direct assault against the British professionals. The battle was an undeniable catastrophe for Gates.[30] The militia quickly folded and threw their weapons down in retreat. The British forces, including Banastre Tarleton’s famed legion of expert cavalry, easily rolled up the Continental’s flank. Gates personally panicked and fled the field before the battle was even finished.

Gates’ fleeing prior to the battle’s conclusion left him permanently disgraced amongst his peers. Gates’ own subordinate, Otho Williams, was at a loss to defend his commander, writing to Alexander Hamilton: “As this step is unaccountable to me you must expect to know the reason another time and from better authority.”[31] Alexander Hamilton added salt to the wound in Gates’ professional reputation, joking: “Was there ever an instance of a general running away as Gates has done from his whole army?” Gates rode over two hundred miles over the next three days, stopping at Hillsborough, North Carolina. To cover that distance so quickly on horseback led to further shame, as Hamilton mocked Gates’ old age: “It does admirable credit to the activity of a man at his time of life.”[32] For all practical purposes, Gates’ military career was over, ending in utter humiliation.

An Uncertain Legacy

Unfortunately, events never improved for Horatio Gates after Camden. To his credit, Gates did his best to reorganize the Southern Department and remained in command until he was relieved by Nathanael Greene in December 1780.[33] Adding to Gates’ misfortune, he received news that his son, Robert, passed away at the age of twenty-two that same year. A despondent Gates left the army and returned home.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, that was still not the end of Gates’ story. Over the next two years, still haunted by his failed ambitions of glory, he ruminated over his disgrace and demanded that his name be cleared by a court inquiry. He found he still had some friends in Congress, and in August 1782 he rejoined Washington’s camp one final time, performing duty at Newburgh, New York.[34]

In hindsight, Horatio Gates’ last action in the Army was yet another unfortunate decision that led to another scandal darkening his legacy. At Newburgh, Gates became associated with the “Newburgh Conspiracy,” a plot by soldiers that considered mutiny and marching on Congress over grievances related to financial payments as the war concluded.[35] Gates offered sympathy and support to his aide, John Armstrong, who wrote a letter that advocated radical action against Congress.[36] Washington famously addressed his officers and put an end to the conspiracy, forever setting the now-sacred precedent of civilian control of the military. Gates, on the other hand, appeared to side with the disaffected soldiers’ radical cause. For this action, in addition to his failure at Camden, Gates’ legacy seems marked by a brilliant beginning considerably darkened by defeat, cabals, and unbridled ambition in the end.

Following the war, Gates retired to Traveler’s Rest. With his son, and now his wife, both having passed away, he found himself in depression and financial troubles. He remarried a wealthy widow, Mary Vallance, and sold Traveler’s Rest to move near New York City.[37] There he spent the remainder of his days in quiet obscurity, mostly staying clear of political scandals and gossip that had so burned him in the past. Without fanfare, Horatio Gates died of natural causes on April 10, 1806, largely forgotten by his country.

Conclusion

Considering his egregious failures, naked ambition, and questionable controversies, where should Horatio Gates land in the American Revolution’s historical memory? Fear not, for I come not to bury Horatio, but to praise him. Ultimately, his achievements were notable, and one cannot overlook the role he played in saving the American cause at Saratoga. Gates’ victory at Saratoga led to the French alliance, an absolutely essential element for the American cause. Without Saratoga, there would have been no Yorktown. As biographer Paul David Nelson points out, Gates was a skilled administrator, and had he remained in his post of adjutant general at Washington’s right hand, he almost certainly would have earned a better place in American history.[38] In 1777, prior to their relationship falling out, Washington wrote of Gates’ performance as his adjutant: “I had in vain cast my eyes upon every person within my knowledge, and found none that I thought equal to the task.”[39] If only Gates had stayed where he excelled! Gates’ later failings in life should not erase his significant contributions to his country.

Ultimately, Horatio Gates’ downfall was his own ambition. In a letter to John Adams, Gates once joked about another Congressional delegate, writing: “Man is the only animal that is hungry with his belly full.”[40] The same words could just have easily been said of Gates. Concerning this fatal character flaw, his life contains a vital lesson. Life will bring both great achievements as well as disappointments. One must take both in stride and not let ambitions go unchecked. In a final note of irony, following his victory at Saratoga, Gates offered precisely this advice for his own son: “Tell my dear Bob not to be too elated at this great good fortune of his father. He and I have seen days adverse, as well as prosperous. Let us through life endeavor to bear both with an equal mind.”[41]

[1]Paul David Nelson makes this point in General Horatio Gates: A Biography (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1976), xi-xii. Early and influential historians like George Bancroft established Gates’ assessment in historiography as an incompetent officer who betrayed Washington. Believing that Gates had been unfairly treated by historians, Nelson argued for a portrait of a simple yet ambitious man with many flaws. Historian Don Higginbotham agreed with Nelson’s sympathetic view of Gates, who despite obvious shortcomings may have been treated too harshly by historians. See Don Higgenbotham’s review of Nelson’s General Horatio Gates: A Biography, The North Carolina Historical Review Vol. 50, No. 3 (July, 1973), 256-272. More recently, Gates’ role in historiography appears to increasingly recede into the background. See Robert Middlekauff’s The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007) and Charles Neimeyer’s The Revolutionary War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007). For additional examples of Gates treatment by historians, see David McCullough’s 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005) and Joseph J. Ellis’ Revolutionary Summer (New York: Vintage Books, 2013) in which Gates makes a fleeting and uncritical appearance.

[2]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 8.

[7]Stephen E. Bower, A Short History of the U.S. Army Adjutant Generals Corps 1775-2013 (Fort Jackson: U.S. Army Soldier Support Institute, 2013), 9-11.

[8]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 43.

[9]Robert K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1983), 30-31.

[10]See for example: Plan for Attacking Boston, February 18–25, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0237. Notice Gates’ signature on the plan. See also for example: Orders and Instructions for Major General Israel Putnam, March 29,1776, Founder’s Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0421.

[11]George Washington to Horatio Gates, March 10, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0580.

[12]From the Diary of John Adams, May 16, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0121.

[13]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 106.

[14]Gates to Washington, July 29, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0369.

[15]Neimeyer, The Revolutionary War, 100.

[16]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 119.

[17]In writing to Congress, Gates included no mention of General Arnold’s role in the victory.

[18]Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause, 279-280.

[19]Charles Thomson to Washington, October 31, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0066.

[20]Washington to Gates, January 4, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0113.

[21]Washington to Patrick Henry, 28 March 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0310.

[22]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 160.

[24]Wayne E. Carp, To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 29-30.

[25]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 187, 205, 210.

[27]Gates to Thomas Jefferson, August 3, 1780,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-0604.

[28]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 221-222.

[29]Quoted in Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause, 333.

[31]Otho H. Williams to Alexander Hamilton, August 30, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0830.

[32]Quoted in Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 237.

[35]The officers demanded “half-pay” for life, and were afraid the war would conclude before Congress secured the measure.

[36]See Glenn A. Phelps, “The Republican General” in Don Higginbotham, ed., GeorgeWashington Reconsidered (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 180. See also Neimeyer, The Revolutionary War, 180, and for a slightly nuanced version, Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause. Middlekauff argues Gates sympathized with the soldiers but withheld his full support of the action.

[37]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 284.

[39]Washington to Gates, March 10, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0580.

[40]Gates to John Adams, April 23, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0055. Gates was referencing Robert Morris.

12 Comments

A nice article summarizing ol’ Granny Gates! I think you nailed him as a highly ambitious, yet limited practitioner in the arts of war and politics. For me, Gates never rises to the occasion where suspicion of his real motives and criticisms of his strategy aren’t lingering over him. Maybe that’s unfair, but his greatest achievement, Saratoga, was in no small part thanks to Arnold.

He reminds me somewhat of Union Gen. George McClellan in how perception carried much of his army through the war (and for their political aspirations). McClellan’s men loved him because they felt he would never recklessly put them in harm’s way during a battle. Because of this, McClellan (unfairly or not) came to be viewed as having ‘the slows,’ coined by Lincoln, in his advancing and positioning. Gates’s troops also had the opinion he wouldn’t deploy them recklessly, earning their respect. Fighting defensively against the British might sound familiar looking at Gen. Washington, but the key difference is Washington fought this way by hard, accepted resolve; Washington had the killer instinct that had to be checked. When events got real, Gates showed an instinct of indecision, panic, and retreat.

Loved your reply, especially comparing Gates to McClellan. If I’m not mistaken Didn’t President Lincoln ask McCellan “if you are not going to use your army, I would like to borrow it”. I have always thought that if Arnold, who disobeyed Gates orders, that Gates could have lost. Regardless, those were 3 Generals who I believe were filled with passions for their own personal glory. But you are the scholar here, and I’m an old lady who is passionate about the American Revolution and The Civil War. Thank you for letting me comment.

Saratoga was every bit the key turning point that you describe, but who really deserves the credit for the American victory? Completely off-the-cuff, I suggest:

50% to the soldiers who fought and died

20% to Schuyler who formed the Northern Army and set up the conditions

20% to Arnold for battlefield leadership without which etc.

5% to Burgoyne for overextending himself when he should have known better

5% to Gates for not managing to screw it up, though not for want of trying (to restrain Arnold for instance)

This article really does spark debate over Gates and his role in the Revolution. I feel Gates was the master “politician” among Washington’s generals. His ambitions were always to get to the next level regardless of his real talent which was administrative duty. This probably stems from his childhood in England. His parents both worked hard, struggled, and got nowhere with very little. Gates skill for taking credit at Saratoga is rich though. I agree Arnold played a role but don’t forget about the real forgotten hero of the Revolution- General Daniel Morgan. He was pivotal along side Arnold for the victory at Saratoga. He picked up the pieces after Gates’s loss at Camden and laid the trap that destroyed Tarelton at The Battle of Cowpens. This major victory led to Yorktown. It is fitting both Gates and Morgan started the war together in the North and ended the war in the South but Morgan was always the one “behind” Gates.

A very nice article, Mike. Also, all great comments above, gentlemen. As some here have mentioned, there are those who debate that it was actually Arnold who was the hero of Saratoga. A good supportive account of that can be read in Chapter 12 of Willard Randall’s biography Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1990), a fair and balanced narrative. Indeed, Gates is just as complex a character as Arnold, Wayne, Lee, Hamilton, Wilkinson, or McIntosh (and Gwinnett)-take your pick or, for that matter, any of the founding fathers. But, Gates’ subterfuge with Wilkinson in the Washington cabal and his disingenuousness at Saratoga regarding Arnold, are the two important strikes out of the three, which make him the “Zero” in my book! Anyway, again, a very nice article and I enjoyed it.

I’d give a high contributory percentage to the rifleman who shot Gen Simon Fraser. I Don’t normally play what ifs, but would Camden have been a disaster on the same scale with Greene in command.

We love to hate him, but Benedict Arnold was correct when he said that Frasier was worth an entire regiment by himself.

If Greene had been in command it is highly probable that Camden would never have occurred.

Clearly, the Battle of Saratoga would not have been won without the heroics of Benedict Arnold. Gates had very little to do with it, but got the credit because he was a better politician.

Did not Greene himself, after viewing the battlefield at Camden on his way to what would become the Battle of Hobkirk Hill, say that if he had been in command at Camden, he would have done much as Gates had?

There is in the Gates Papers a letter from the Secretary of the Board of War instructing Gates to go IMMEDIATELY into South Carolina and establish a presence there. The letter goes on to state that negotiations were under way, or about to become so, with the Spanish to try and convince them to send troops and actively participate in the Southern Campaign. That Gates followed orders is hardly indicative of uncontrolled personal ambition.

How did Gates’s son Robert die? I have not been able to find out, even on genealogy sites. It appears to have been in late 1780, at age 22.

I did come across this record, it adds a little bit:

He died in 1780, in German Flatts, Herkimer, New York, United States, at the age of 24.