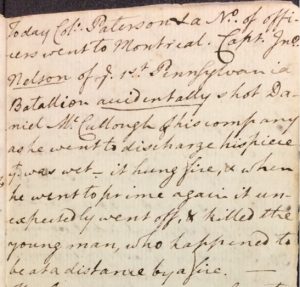

In 1901, the American Monthly Magazine published Rev. David Avery’s journal of the 1776 “Northern Campaign.” Avery had served as chaplain for John Patterson’s Massachusetts Regiment (15th Continental) and his chronicle provided an interesting primary source account of the failed campaign in Canada that spring. The printed journal described a minor, but tragic, accident that occurred near Fort Anne, on May 28:

Capt—of [the] 1st Pennsylvania Batallion accidentally shot Daniel McCullough of his company as he went to discharge his piece [that] was wet—it hung fire & when he went to prime it unexpectedly went off, & killed the young man, who happened to be at a distance by [the] fire. His funeral was decently attended.[1]

The American Monthly Magazine’s editor, Catherine H. T. Avery, did not explain why the captain’s name was omitted in this Daughters of the American Revolution publication. Perhaps she wished to avoid any potential embarrassment to descendants of the officer involved. The Rev. David Avery, however, had no such qualms in his original manuscript. Where Catherine Avery had politely printed a long line, the reverend’s original journal identified the officer as “Jno Nelson.”[2]

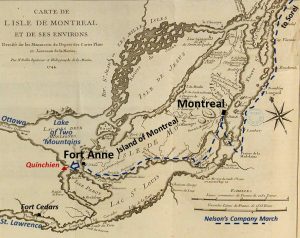

Capt. John Nelson commanded an independent Pennsylvania rifle company of backcountry men, formed in early 1776 for service in the north. After Nelson’s company reached Canada in mid-May, it was attached to Col. John Philip de Haas’s 1st Pennsylvania Regiment. At the time, a combined Native and British force actively threatened American-occupied Montreal from the direction of the Great Lakes, so de Haas was ordered to take several companies west to reinforce the Continentals’ vulnerable flank. David Avery reported the Pennsylvanians’ arrival in Montreal on May 24: “Colo. Dehoise arrived [that] Evg. from Sorell with 400 men.” The next day, Avery noted that “Abot. 400 men & myself marcht to La Chine from Montreal”—Nelson’s riflemen were among them. They soon joined an ad hoc Continental corps that Gen. Benedict Arnold was assembling to counter the enemy threat.[3]

On May 26, Avery’s journal continued, “About 950 men marcht to Fort St. Ann, under command of General Arnold, 18 miles up [the] St. Lawrence from La Chine.” As one of Nelson’s riflemen recalled, their mission was to “releive six hundred prisoners taken by the enemy and Indians at a place called the Cedars.” The British and their Indian allies retreated with their prisoners rather than face Arnold’s numerically superior force. Late that afternoon, the Continentals reached the island’s western tip at the castle-like manor that they called Fort Anne or Ste Anne.[4]

The composite British-Native-Canadian force had since abandoned the Island of Montreal on their western retreat. The Americans could spy them, however, two miles across the broad Lake of Two Mountains that separated the Island of Montreal from the mainland. On the evening of May 26, David Avery recorded that: “General Arnold with about 350 [men] in boats made a pretence of landing” on the opposite shore “to attack [the] enemy just at sunset.” Some of Nelson’s riflemen may have been involved in this waterborne approach. As Avery continued, Arnold and his men “were repulsed by a very brisk fire from [the] cannon & small arms.” Nightfall limited the general’s immediate options, so he ordered his men back to Fort Anne.[5]

The Continentals regrouped around the fort that night. Arnold and his senior officers planned to strike the enemy the next day, but there was a certain sense of dread knowing that enemy warriors had threatened to summarily kill all American captives if attacked. General Arnold’s plans were upended, however, when a British officer arrived in the middle of the night under a flag of truce. He delivered a prisoner exchange proposal. With the American prisoners’ lives weighing heavily on his mind, Arnold negotiated a “cartel” agreement rather than resume the offensive. Later that day, Avery reported, “The cartel finished. Cessation of arms for 4 days.” Nelson and his riflemen were idling at Fort Anne under this cease fire when the accident described in Reverend Avery’s journal took place.[6]

A second primary source, an orderly book of the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion of Foot, provided further detail of the accidental discharge incident. On May 28, the same day that Nelson inadvertently killed one of his riflemen, Colonel de Haas ordered a court of inquiry “to see why and in what manner Daniel McCullough came by his Death.”[7] Seven junior New England officers, led by Capt. David Noble, conducted the inquiry. The next day, they reported:

Having carefully examined the Witnesses relating to this unhappy event, it appears to the Court to have happened in the manner following, vizt. That Captain John Nelson having Liberty to discharge his piece that was wet, it hung fire; upon which he lowered his Gun in order to prime again, and it went off unexpectedly to the Captain, and accidentally killed the said Daniel McCullough.[8]

It is noteworthy that the court specified that Captain Nelson had “liberty” to discharge his wet rifle. Unauthorized musket fire was a regular discipline problem in Continental camps. It remains unclear, though, how Nelson’s rifle came to be wet. Various primary source accounts from the region note that the weather that day was clear and cold and none of them mentioned precipitation the previous day, either.[9]

Following Daniel McCullough’s tragic death, Captain Nelson was initially engrossed in leading his riflemen out of Canada as they joined the Northern Army’s disorganized mass retreat back toward Ticonderoga. After many weeks of tedious camp duty there, the captain wrote directly to Congress in August, requesting that his company be reposted on the Pennsylvania frontier. This was not approved. Apparently eager to move on, the captain left his men behind in November anyway. He headed home to recruit a company for service in 1777. He received a new 9th Pennsylvania Regiment commission in December—even though his independent company riflemen’s enlistments did not expire until February. Nelson took time from his recruiting tour to close the books on his old company in March, when he met returning riflemen in Philadelphia to issue discharges.[10]

Captain Nelson’s military life quickly spiraled out of control after that. In what Alexander Hamilton described as “a complicated business,” Nelson was found guilty of having “sold” thirty-one of his new recruits to another regiment, and was cashiered from service; yet the 9th Regiment’s commander, Col. George Nagle, kept him under arrest into the summer of 1778. There is no obvious record of the captain’s public activities thereafter. John Nelson’s Continental military career catastrophically burned out within fourteen months of his fatal Fort Anne mishap.[11]

[1]Rev. David Avery, “Northern Campaign,” American Monthly Magazine18 (March 1901): 240. Avery used “ye” and “yt” for “the” and “that.”

[2]May 28, 1776, David Avery Journal, David Avery Papers, Box 1, Ms 20788, Connecticut Historical Society. Catherine Avery’s husband Elroy did not have direct lineage to the reverend, but his extended family relations led her to David Avery’s journal; Elroy M. Avery and Catherine H. T. Avery, The Groton Avery Clan, vol. 1 (Cleveland, 1912). The Pennsylvanian John Nelson was not a registered ancestor on Daughters of the American Revolution rolls in 1901, although other John Nelsons were.

[3]May 24 and 25, 1776, Avery, “Northern Campaign,” 239; Thomas L. Montgomery, ed. Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series (Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Printing Company, 1906), 2: 63; Mark R. Anderson, Down the Warpath to the Cedars: Indians’ First Battles in the Revolution (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021), 111. Curiously, the only other significant American Monthly Magazine omission from the original manuscript journal came in a May 25 entry about casualties from the enemy ambush of a relief column headed for The Cedars. Avery wrote: “Hear [that] one man made his escape from [the] Cedars & informs [that] 10 only of [Maj. Henry] Sherburne’s party were killed—not one officer.” The magazine, however, did not include the comment “not one officer”—perhaps the editor believed this might be interpreted to be disparaging the officers’ courage in battle.

[4]May 26, 1776, Avery, “Northern Campaign,” 239; Evan Morgan, S11098, p3, RG15, Revolutionary War Pensions M804, National Archives and Records Administration (M804); Anderson, Down the Warpath to the Cedars, 118-19. The fortified estate was also known as Fort Senneville.

[5]May 26, 1776, Avery, “Northern Campaign,” 239.

[6]May 27, 1776, Avery, “Northern Campaign,” 239; Anderson, Down the Warpath to the Cedars, 119-21, 122-24.

[7]May 28, 1776, Fort Ann, Orderly book of the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion of Foot, Society of the Cincinnati. The author’s Society of the Cincinnati research was supported by a generous fellowship from the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati.

[8]May 29, 1776, Fort Ann, Orderly book of the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion of Foot, Society of the Cincinnati.

[9]May 28, 1776, Avery, “Northern Campaign,” 240; “Journal of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Vose,” Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Volume VII, Transactions, 1900-1902 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1905), 256; The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, 1775-1778, Thomas William Baldwin, ed. (Bangor, ME: The De Burians, 1906), 49.

[10]John Nelson to President of Congress, August 23, 1776, Peter Force, ed., American Archives. Fifth Series(Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837–53), 1:1129; Evan Morgan, S11098 p3, John Cunningham, S16749 p3-4, and Thomas Downey, S35895 p4, M804; General return of Ninth Pennsylvania Regiment, July 17, 1777, Montgomery, ed., Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, 3: 394.

[11]Alexander Hamilton to Anthony Wayne, August 24, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0538; General Return of Ninth Pennsylvania Regiment, July 17, 1777, Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, 3: 394; John B. B. Trussell, The Pennsylvania Line: Regimental Organization and Operations, 1775, 1783 (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1993), 113.

Recent Articles

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

Recent Comments

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

It seems there is no way to know the details of the...