William Goforth played significant roles in New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio in the age of the American Revolution and the Early Republic and he stands out across the centuries as a man who lived by enlightened values. Yet even though he corresponded or directly cooperated with several very famous counterparts—the likes of Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson—Goforth has remained in history’s shadows. He never rose to high rank or office, but he was a man of strong character, with an inquisitive mind, sagacity, effective leadership skills, and a bit of playfulness—attributes that are evident at several points in his life. As someone noted in the Goforth family Bible upon his death, “He lived Respected and Died Regreted, By All who know’d his merit.”[1]

William Goforth’s youth is scantly documented for almost three full decades after his Philadelphia birth on April 1, 1731. At some time during the French and Indian War, he served as a “captain of marines” aboard a privateer; but it was not until 1760 that he was first recorded as a “labourer” in New York City’s rolls of freemen. That year he also married Catherine Meeks, thirteen years his younger, in New York City’s First Baptist Church. Before the Revolutionary War, Goforth made his living as a cordwainer (leather shoemaker) and small-scale merchant.[2]

Goforth’s earliest political activity seems to have been prompted by his Baptist affiliation. In 1769, he was a founding member of New York City’s Society of Dissenters, a group of eighteen men who cooperated “for the preservation of their common and respective civil and religious Rights and Privileges,” which they felt were impinged upon by the colony’s established Anglican Church. Society efforts brought Goforth into close contact with rising revolutionaries Alexander McDougall and John Morin Scott. In the early 1770s however, he apparently focused on his business and supported Catherine in raising their three young children—William, Mary, and Tabitha—born from 1766 to 1774.[3]

The momentous revolutionary events of 1774 called Goforth to political action. As a representative of New York City’s “mechanics,” or artisan class, he rose to new levels of responsibility. Goforth was elected to both the Committee of Sixty and the Committee of One Hundred, the major political bodies established to channel the city’s growing Continental-Patriot spirit. The character of his patriotic duties abruptly changed, though.[4]

In June 1775, Goforth’s friend Alexander McDougall was given command of the newly formed First New York Regiment. The forty-four-year-old Goforth soon heeded the call to arms. As characterized in the conclusion of a poem he composed in his personal daybook, playing upon his own name and one of the tools of his trade, he asked “What! not Goforth? when Awl’s at Stake.” He was appointed captain of McDougall’s fourth company and had notable recruiting success. The new captain eventually led ninety-three men and two lieutenants when they marched from New York City. Goforth’s relatively low social position, however, was reflected in an appeal that he and three fellow officers made to the provincial congress. They sought assistance in acquiring uniforms and weapons, as they did not have the personal wealth of those traditionally called to serve in such positions.[5]

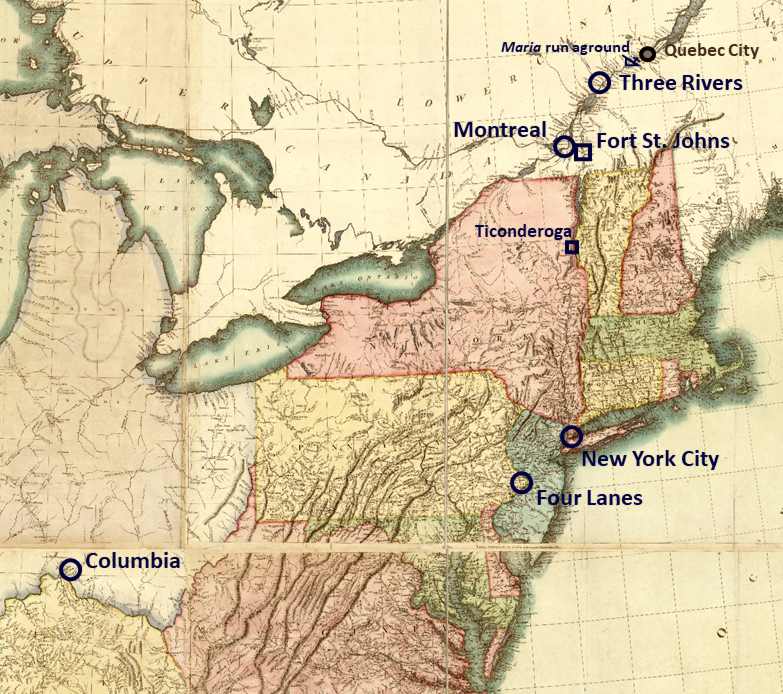

Goforth led his company out of New York in the first week of September and had crossed the border into Canada by the 18th. He and his men soon joined the Continental siege of British Fort St. Johns, giving Goforth a taste of both combat and the misery of military life in a sodden, muddy, disease-filled camp. The middle-aged captain quickly established a fatherly mentor relationship with many of the regiment’s young officers. Goforth also began sharing field updates in letters to Colonel McDougall, who had remained behind in New York City. Fort St. Johns surrendered on November 3 and the army marched on to enter Montreal without a fight, ten days later.[6]

After taking the city, most soldiers rushed home since their enlistments were expiring by the end of the year. However, a few hundred reenlisted through April 15, 1776, with Goforth leading many of his men among them. Toward the end of November, when Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery led the bulk of the winter soldiers north to join Benedict Arnold outside the last British-Canadian stronghold at Quebec City, Goforth’s company stayed behind in Montreal. He and his men garrisoned the occupied city and occasionally ventured into the countryside to arrest troublesome Loyalists, who had become even more problematic in early 1776 with word of Montgomery’s fatal New Year’s Eve defeat at Quebec City.[7]

Toward the end of January, Captain Goforth received orders to take his company to the city of Three Rivers (Trois Rivières), where he would “Curb the Tories” and act as a district military governor for a region encompassing the city and seventeen parishes between the Montreal and Quebec districts. Upon arrival on February 8, 1776, Goforth and his men settled into the government barracks—their primary duties were to supply soldiers marching to Quebec City and implement military orders in the district, which he judged to be “the quietest and best Disposed part of Canada.” While there, he also wrote to John Jay and Benjamin Franklin to share the desperate strategic situation in Canada and offer recommendations to those prominent leaders. The journal of Loyalist notary Jean-Baptiste Badeaux records the captain’s prudent and generally effective civil-military relations; but Goforth lamented his inability to curb ill-disciplined American soldiers’ abuse and robbery of rural Canadians as Continental reinforcements passed through the district en route to Quebec City. Goforth’s comfortable Three Rivers command effectively ended at the expiration of his men’s enlistments on April 15.[8]

Nine days later, Goforth received new orders to captain “a privateer” on the St. Lawrence River, the sixty-six-foot, ten-gun schooner Maria, even though he readily admitted that he was “no Sailor.” His first mission was to patrol the river, interdicting supply shipments that Loyalists might try to sneak into Quebec City. The command was short lived. On May 6—the very day that the first British reinforcements arrived to relieve the besieged capital—the Maria encountered a Royal Navy ship. Goforth reported that “the frigate gave him chase; he crowded all sail possible, but found it in vain,” and he grounded his schooner near Pointe-aux-Trembles (Neuvillle), escaping with thirty-seven of the ship’s thirty-nine crew members. After almost eight months of duty in Canada, Goforth’s military responsibilities were complete—with his company dissolved and his ship in enemy hands, he no longer held a command—so he headed home.[9]

As Goforth passed through Ticonderoga on May 16, 1776, he delivered official messages from leaders in Canada to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler. When he arrived home in New York City, he delivered some correspondence from Schuyler to Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, temporarily in command of the army while General Washington was in Philadelphia. After spending a few days with Catherine and his children, including five-month-old son Aaron, Goforth dutifully returned to Ticonderoga on one more courier mission, bearing messages from Washington to Schuyler.[10]

In June, it seemed as if Goforth might progress up the officer ranks, having been appointed major in a newly formed New York regiment. Goforth, however, saw this posting as a slight, rather than an honor. During his time in the army, Goforth shared a very common “republican” attitude as a stickler for the principle of seniority as the primary basis for military promotion; and the new regiment’s commander and lieutenant colonel had both been junior in rank to him.[11] As a result, Major Goforth wrote to the New York Provincial Congress on July 5 and declined further service. He considered an appointment “under two junior officers” to be “no more than taking the most genteel way of discharging” him from “the publick service as an officer.” New York’s assembly accepted the resignation with apparent good will, recognizing him as “a brave and good officer.” When New York made subsequent attempts to call on him for officer duty in the following year, he declined further service.[12]

Back in New York City in the summer of 1776, Goforth returned to civic venues in his support of the Continental cause. Shortly after resigning his commission, he joined more than one hundred memorialists who made a direct appeal to General Washington, whose Continental Army occupied the city and surroundings. Deeply concerned about the region’s internal Loyalist threat, they asked “that orders may be given for the removal of dangerous persons from this city.” Washington subsequently honored Goforth as one of just six civilians authorized to grant travel passes in the New York City region. In a concurrent business endeavor, Goforth joined four fellow veterans by accepting an official city appeal for establishment of a salt works; however that enterprise proved to be short lived. When the conquering British army arrived in the city that September, the Goforth family departed their home and abandoned the business, rather than suffer under tyrannical occupation.[13]

It is possible that William, Catherine, and their four children stayed in the New York countryside for a short while. Family tradition said that Goforth served as a spy in the region as late as 1780. This story might have been embellished—Catherine was in Philadelphia for the birth of daughter Jemima on May 9, 1778; and William was confirmed to be in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, by October 1779, when he purchased Loyalist Gilbert Hicks’s “Four Lanes” estate in what is now Langhorne Borough. Other cherished family stories from later generations said that the Goforth family hosted Washington and Lafayette at their new home for “secret meetings” during the Valley Forge winter of 1778.[14]

The Goforths remained in Bucks County for the rest of the war, where Catherine bore their last two children. In 1781, William served for a short time as a Pennsylvania state auditor, handling army pay depreciation claims. Apparently in financial distress, he made unproductive attempts to sell “Four Lanes” as early as December 1782. Goforth subdivided the estate into smaller parcels in early 1783 to encourage sales and intended to form a planned settlement with designated plots for churches and schools. This enlightened hamlet, dubbed “Washington Village,” was to have streets named after Goforth’s notable associates from military service, including Montgomery, McDougall, Willett, and Lamb; but the effort never came to fruition and Goforth remained short of cash.[15]

With war’s end and the British army’s November 1783 departure from New York, the Goforths finally returned home. William promptly distinguished himself as “an earnest advocate of popular rights and popular education.” In January 1785, he co-founded the New York Manumission Society. Later members such as Alexander Hamilton and John Jay have received more historical recognition for their prominent participation; Goforth, however, was one of the society’s leading workhorses. In 1786, he participated in a committee seeking funds for a “negro childrens’ school,” and in 1787, served as the society’s vice president.[16]

Concurrent with his society duties, in 1784, Goforth was elected to the New York State Assembly with the endorsement of the “Sons of Liberty.” He was one of just two “mechanics” elected in the first post-occupation legislature. Serving two consecutive terms, he built upon his Manumission Society activities by promoting a law to free children born to enslaved women after 1785.[17]

Yet while William Goforth was making social and political impacts, his financial situation continued to deteriorate. As an associate recorded, “the war injured him & he has met with Losses in Trade, he has failed.” By 1787, he owed the tremendous sum of £5,100 sterling. William and Catherine made the difficult decision to join their grown children’s families that had already headed west, staking their future on the Ohio frontier. Goforth settled accounts as best he could, but was forced to leave his real estate property in the hands of creditors, who eventually sold it at public auction. On September 26, 1789, fifty-eight-year-old William left New York City for the last time and headed to the Northwest Territory.[18]

Goforth reached what would become his new home on January 18, 1790, a small Ohio River settlement at Columbia, Ohio, near Cincinnati. Two days after his arrival, he joined in establishing the community’s Baptist church, and in less than two years, was spearheading plans for a local “educational academy.” In 1790, Territorial Governor Arthur St. Clair recognized Goforth’s prominence when he appointed William as a judge for the newly established Hamilton County court of common pleas. In this service, Judge Goforth was recognized for his “integrity and independence,” controversially arresting drunken federal soldiers and shutting down local liquor peddlers. In 1801, Secretary of State James Madison appointed Goforth as a federal commissioner to settle disputed territorial land claims. Meanwhile, William and his extended family constantly improved their settled property. They also accumulated hundreds of additional acres in the region, although some of the land was of questionable value.[19]

Goforth’s next major undertaking was advocacy for Ohio statehood. Despite Federalist Governor St. Clair’s opposition, in 1797 Goforth helped generate a circular letter seeking other counties’ support in the cause. In January 1802, he boldly wrote to President Thomas Jefferson, conveying his fellow Ohio republicans’ issues with “the Government of the Northwestern territory,” and enclosing a petition for Ohio statehood. His letter complained that Ohioans had suffered “deprivation of those privileges injoyed by our fellow citizens in the States in the Union,” and appealed to the president “to restore us to the precious privilege of a free Elective Republican Government.” Hearkening back to the great revolution, which was almost thirty years in the past, he complained that

our ordinance Government it is a true transcript of our old English Colonial Governments, our Governor is cloathed with all the power of a British Nabob, he has power to convene, prorogue and dissolve our legislature at pleasure, he is unlimitted as to the creation of offices, and I beleive his general rule is to fill all the important leading offices with men of his own political Sentiments.

Goforth recorded several specific cases of Governor St. Clair’s manipulative misrule and provided detailed population estimates to support the statehood appeal. In April 1802, Congress authorized the inhabitants to meet that November to form a state constitution. William Goforth attended the convention, serving as president pro tem. His mission was complete when the State of Ohio officially joined the union the following year.[20]

Goforth accepted one final political role in 1804, leading Ohio’s Republican Electoral ticket and casting votes for Thomas Jefferson and George Clinton. In his last three years, Goforth effectively disappeared from the historical record until his November 2, 1807, death at age seventy-six, in Columbia, Ohio. His wife Catherine survived him for another twenty years. His son Dr. William Goforth was renowned as the first prominent medical doctor west of the Appalachians, and for his role in excavating mastodon bones at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, drawing President Jefferson’s attention and a visit from Meriwether Lewis. In the extended Goforth family, two of Judge William Goforth’s sons-in-law achieved regional prominence as well: John Stites Gano, husband of eldest daughter Mary, became a major general in the Ohio Militia; daughter Tabitha’s husband John Armstrong was also an officer and served as a county and territorial official.[21]

Biographer William H. Chatfield reflected on the sum of William Goforth’s life, “Few colonial gentlemen could match Goforth’s varied and unique accomplishments. His values, ethics, manners, and civic accolades set a high standard for ensuing generations.” An obituary penned by a contemporary noted that Goforth distinguished himself in every one of his major roles: “As a soldier he had patriotism, courage, and honor; as a legislator he had wisdom & Republicanism; as a judge he had integrity and independence . . . in the humble & domestic relations of husband, father and neighbour he shone with a steady and native lustre. . . . He loved us, his country & the world: he practiced the strictest justice, purest morality & most disinterested benevolence.” William Goforth should be remembered as one of many patriotic Americans who never rose to the highest military ranks or civilian offices, yet still performed many essential roles in the birth and growth of their new nation.[22]

[1]This article has been adapted with new content, by permission of the publisher, from Mark R. Anderson, ed. and Teresa L. Meadows, transl., The Invasion of Canada by the Americans, 1775-1776: As Told through Jean-Baptiste Badeaux’s Three Rivers Journal and New York Captain William Goforth’s Letters (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016), (hereafter cited as Invasion of Canada); Goforth Family Bible (1728), Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

[2]Goforth Family Bible; New-York Historical Society (hereafter cited as NYHS), “The Burghers of New Amsterdam and the Freemen of New York, 1675–1866,” in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1885 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1886), 194; David Wooster to Hector McNeil, April 28, 1776, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bf9cc762-78b3-8c19-e040-e00a18060263.

[3]“The Society of Dissenters Founded at New York in 1769,” The American Historical Review 6, no.3 (April 1901): 498–502; Goforth Family Bible.

[4]New Committee of Sixty Elected, November 22, 1774; New General Committee for the City and County of New York Elected, May 1, 1775; Peter Force ed., American Archives, Fourth Series (hereafter cited as AA4), (Washington, DC: 1837–1853), 1:330, 2:459.

[5]Captains Appointed by the New York Provincial Congress, July 6, 1775, AA4, 2: 1592; William Goforth Day Book, John Armstrong Papers, Indiana Historical Society; State of the Four Regiments raised in the colony of New York, August 4, 1775, rg93, v5, r15, p152, Numbered Record Books (M853), U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter cited as NARA); Muster Roll of Captn Goforth’s Compy, September 19, 1775, rg 93, r65, f1, p33, Revolutionary War Rolls (M246), NARA; To the Honourable Provincial Congress, July 26, 1775, AA4, 2:1729.

[6]New-York Journal, September 7, 1775; Mate of a Vessel on Lake Champlain . . ., September 18, [1775], Peter Force ed., American Archives, Fifth Series(hereafter cited as AA5) (Washington, DC: 1837–1853), 2: 386; William Goforth to Alexander McDougall, October 1 and October 22, 1775, Invasion of Canada, 16-18, 31-33.

[7]Goforth to McDougall, November 22, 1775, January 1 and 5, 1776, Invasion of Canada, 44-46, 52-53, 56-58.

[8]Goforth to Alexander McDougall, January 27, February [n.d.], and April 21, 1776; Goforth to Benjamin Franklin, February 22, 1776, Goforth to John Gano, March 24, 1776, and Goforth to John Jay, April 8, 1776, Invasion of Canada, 63, 72-73, 74-78, 96-97, 100-1, 136, 138, 142, 144. See also Badeaux journal entries for February, March, and April in same. Many Goforth biographical accounts mistakenly credit him with participation in the Battle of Three Rivers (June 8, 1776), apparently confusing his occupation duty in the city with the battle fought nearby after he had already returned to New York. The error has propagated over the years from early works.

[9]Goforth to Alexander McDougall, April 21, 1776, Invasion of Canada, 144 and 160-61; Charles Douglas to Philip Stephens, May 8, 1776, William B. Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969), 4: 1454; Wooster to McNeil, April 28, 1776 (cited above); Israel Putnam to George Washington, May 21, 1776, Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (hereafter cited as PGWRWS) (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1983–1991),4:358-60.

[10]Philip Schuyler to George Washington, May 16 1776; Washington to Schuyler, June 15, 1776, PGWRWS, 4:316–19, 531–39.

[11]For Goforth’s thoughts on seniority as the foundation for military promotion, see Goforth to McDougall, January 19, 1776, Invasion of Canada, 60-61. The new regiment’s colonel and lieutenant colonel were Lewis Dubois and Jacobus Bruyn. Transcript of General Schuyler, “A List of officers . . . as they Rank 28 Feby 1776,” rg93, r178, f181, p230, Papers of the Continental Congress (M247), NARA.

[12]Goforth to New York Provincial Congress, July 5, 1776, AA5, 1:203–204; New York Convention to the President of Congress, July 11, 1776, AA5, 1:202; Rudolphus Ritzema to New York Convention, August 1, 1776, AA5, 1: 1467; Henry Beekman Livingston to George Washington, February 15, 1777, PGWRWS, 8:342–43.

[13]Memorial of Sundry Inhabitants of the City of New York to George Washington, July 14, 1776, AA5, 1:335; Goforth and John Houston to New York Provincial Congress, August 3, 1776 and New York Convention, August 5 and 6, 1776, AA5,1:1475–76; General Orders, PGWRWS, 5:672–75; William H. Chatfield, Two Revolutionary War Patriots: Major William Goforth and Captain John Armstrong; Epic Struggles Against British Suppression and Indian Warfare (Cincinnati: Pendleton House, 2011), 16.

[14]Chatfield, Two Revolutionary War Patriots, 16, 18–19, 29; Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, October 4, 1779, Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg: Theo. Fenn, 1853), 12:156; Goforth Family Bible.

[15]Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, March 3 and June 6, 1781, Minutes, 12:646, 747; Goforth Family Bible; W. W. H. Davis, The History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, From the Discovery of the Delaware to the Present Time (Doylestown, PA: Democrat Book and Job Office, 1876), 172; intent to sell, Freeman’s Journal (Philadelphia), February 5, 1783; Washington Village plan, Independent Gazetteer (Philadelphia), November 29, 1783.

[16]New-York Manumission Society Records, 1785–1849, 5:27, 122, 126, NYHS; New York Packet (New York City), November 17, 1786.

[17]Independent Journal(New York), April 21, 1784; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 280; Stephen C. Hutchins, Civil List and Constitutional History of the Colony and State of New York (Albany: Weed, Parsons, 1880), 282–83.

[18]David Jones to George Washington, January 13, 1790, Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 4:568–69; Chatfield, Two Revolutionary War Patriots, 30–33; “Extracts from memorandums made by Judge William Goforth, in his day book,” in The Cincinnati Miscellany, or Antiquities of the West, ed. Charles Cist (Cincinnati: 1845), 1:172.

[19]“Extracts from memorandums made by Judge William Goforth . . .” and “Extracts from Judge Goforth’s Docket,” Cist, Cincinnati Miscellany, 1:173–74, 187; John C. Hover et al., eds., Memoirs of the Miami Valley, vol. 2 (Chicago: Robert O. Law, 1919), 618; Roderick Burnham, Genealogical Records of Henry and Ulalia Burt . . . from 1640 to 1891 (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood and Brainard, 1892), 71–72; Albert Gallatin to Thomas Jefferson, October 6, 1801, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 35:391–92; Chatfield, Two Revolutionary War Patriots, 40, 42.

[20]Julia Perkins Cutler, Life and Times of Ephraim Cutler (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke, 1890), 319; Goforth to Thomas Jefferson, January 5, 1802, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 36:297–303; “Chillicothe, NWT, Nov. 6,” Mercantile Advertiser (New York City), December 7, 1802.

[21]Scioto Gazette(Chillicothe, OH), October 29 and December 10, 1804; Goforth Family Bible.

[22]Chatfield,Two Revolutionary War Patriots, 59; Daniel and Benjamin Drake Papers, 1787–1853, Draper Manuscripts, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2O, v2, 197.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...