Throughout history, changes in political order have often been accompanied by the destruction of the old regime’s images and monuments. The July 9, 1776 destruction of King George III’s New York City statue is the most famous and persistent image of such iconoclasm in the American Revolution. In that particular event, after a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, soldiers, sailors, and Sons of Liberty toppled, mutilated, and recycled the city’s most prominent symbol of royal rule. As historian Wendy Bellion noted, “there would seem to be no clearer way to signal the beginnings of the United States than a ritualistic killing of the British King.” But in her analysis of the event, Bellion also commented: “Although artists and writers would later represent the assault on the Bowling Green statue as an anomalous, even epochal, event of the Revolution, the statue’s destruction transpired within [a] much larger field of iconoclastic actions in Britain and British America.” In fact, New York’s famed episode of political iconoclasm was not the first of its kind in the war. In 1775, vandal-activists defaced a marble bust of King George III in Montreal, and six months later revolutionaries destroyed the same monument.[1]

The Bust

While the famous equestrian monument in New York and the lesser-known bust in Montreal honored the same king, they had different origins. New York’s general assembly had obtained that colony’s statue itself, while Montreal’s came indirectly as a charitable donation. A terrible May 8, 1765 fire destroyed much of the vibrant fur-trade city of Montreal, and London donors responded with a gift of £8,415 and two fire engines—intended to aid the city’s recovery and help bind the king’s new Canadien (French-Canadian) subjects to the empire. The colony had only been formally acquired from France two years earlier, at the end of the Seven Years War. Charitable subscription leader Jonas Hanway apparently persuaded the king to donate a marble bust of himself from his own collection, along with £500 for the cause. The art piece had been sculpted by Joseph Wilton—who would later craft New York’s monument, too. Before the donations left England, Hanway added an inscription to the bust’s base, extolling the king’s benevolence: “Temporal and eternal happiness to the sovereign of the British Empire GEORGE III who relieved the distresses of the Inhabitants of his City of Montreal Occasioned by the Fire MDCCLXV.”[2]

On September 12, 1766, the relief package arrived in Montreal on the same ship that brought new Lieutenant Governor Guy Carleton to the Province of Quebec. Carleton, who would be promoted to governor two years later, faced a colony stressed by ethno-religious political discord. A few hundred recently settled Protestant, Anglophone “old subjects” sought a traditional representative government that would privilege them over the province’s approximately eighty thousand French Catholic“new subjects,” who were unqualified to participate in government under conventional British oath requirements. Carleton, however, favored accommodation of the king’s new subjects as active participants in colonial government, aiming to foster their embrace of the empire.[3]

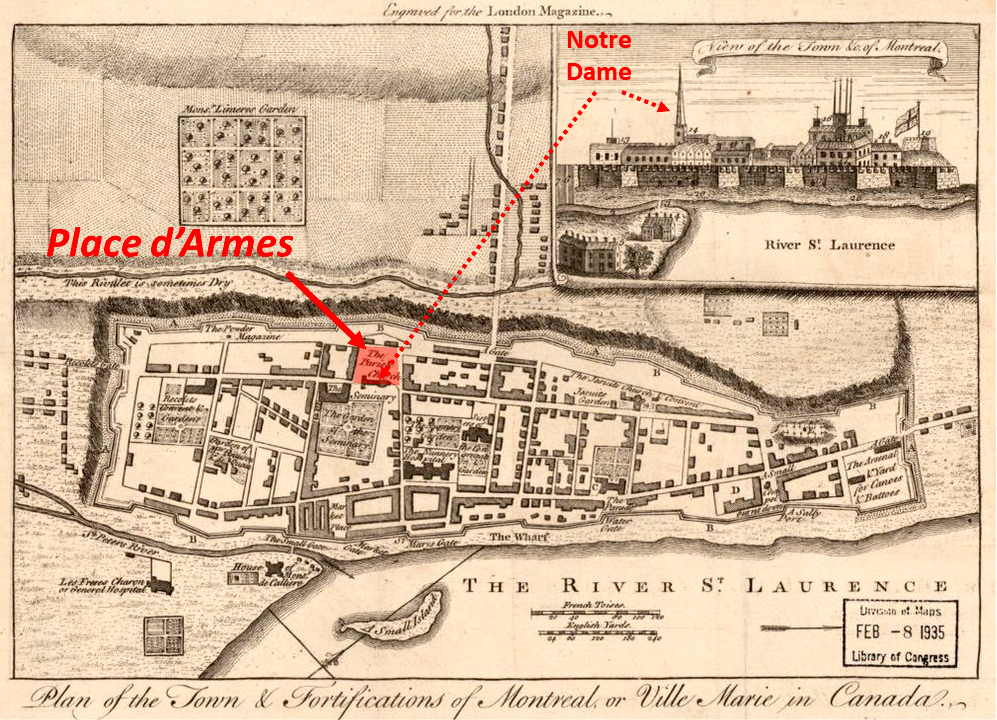

King George III’s bust was kept behind doors for several years until officials decided to display it on Montreal’s Place d’Armes, the city’s main gathering place—creating a monument that “asserted British sovereignty” over the substantial ville of approximately ten thousand citizens. To protect the marble bust through the seasons, Montrealers built a kiosk shelter that faced the entrance of Notre Dame church. The October 7, 1773 installation ceremony gave French-Canadian elites an opportunity to demonstrate their growing attachment to the British king and empire. Chevalier Luc de Lacorne zealously—but unsuccessfully—begged church authorities to toll Notre Dame’s bells for this civil ceremony. An anonymous Francophone poet had more success celebrating the moment when the Quebec Gazette published his amateurish lyrical exultation of the king. Once this Canadien devotional eruption passed, the bust stood as a silent, untarnished monument to empire for just another year and a half.[4]

Political Vandalism, May 1, 1775

Governor Carleton’s political efforts ultimately bore fruit in the Quebec Act of 1774, formally opening office-holding opportunities for Catholic Canadians and securing their church’s place in the province. It would enter effect in May 1775. The province’s noble elite and senior church officials were enthused by the act, while outraged Anglo-Canadians fought for the act’s repeal through the winter and spring of 1774-1775. They were further encouraged by American correspondents who courted Canadian participation in the “common cause” against the British ministry’s “Intolerable Acts.”[5]

Then, on the morning of May 1, 1775—the first day of the Quebec Act government and less than two weeks after hostilities commenced at Lexington and Concord—Montreal citizens awoke to find that “some malicious and mischievous person or persons disfigured the king’s bust on the parade.” Vandals had smeared the royal image with tar, and placed a rosary-like necklace of potatoes around its neck from which hung a wooden Cross, inscribed “VOILÁ LE PAPE DU CANADA ET LE SOT ANGLOIS” (This is the Pope of Canada and the Fool of England). This was undoubtedly a protest statement against the Quebec Act. Two army sergeants were dispatched to clean the bust while Montrealers rushed to place blame based on political and ethno-religious prejudices. The city’s Anglo merchants immediately demonstrated collective innocence by announcing a £100 reward “to any person who should discover the offender.” Army officers followed with a similar offer.[6]

The outrageous incident soon ignited smoldering tensions in Canada—an observer noted that the unidentified culprits presumably had “an intent . . . of creating jealousies, animosities and disturbances amongst the people, particularly between the English and Canadians . . . they have met with great success.” On May 2, citizens gathered on the Place d’Armes, anticipating formal publication of the officers’ reward when a fracas broke out in the crowd. Chevalier François-Marie Picoté de Belestre—one of seven French-Canadians newly appointed as legislative councilors under the Quebec Act government—loudly announced his hope that the perpetrators would be found and face the executioner. When merchant David Salisbury Franks scoffed at the idea of capital punishment for this act of vandalism, the two exchanged insults and then resorted to blows. Franks had hardly stormed off when another fight broke out between pioneering fur-trader Ezekiel Solomon and prosperous shopkeeper Charles Laferte Lepailleur over which ethnic group was probably to blame for defacing the king’s bust. The political vandals’ message had truly exposed Canada’s underlying political and ethnic fracture points.[7]

After word of the bust defacement reached Governor Carleton, he issued an additional government reward of two hundred dollars on May 8, but the vandal-provocateurs would never be identified. Accounts of the insult to the king’s Montreal bust and the ensuing fights soon appeared in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania newspapers and eventually reached England, too. Even if the insult to the bust was clearly aimed at the Quebec Act rather than the broader “Continental” rebellion, it was still the first North American political act against a monument to British authority in the course of the Revolutionary War.[8]

Destruction in Montreal, December 15, 1775

The people of Canada spent the tense summer of 1775 under martial law, anticipating a rebel American invasion that finally came on September 5. After the Continental Northern Army conquered Fort St. Johns in early November, the path to Montreal was clear. On November 13, citizens opened the city to Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery’s American soldiers—British officials and soldiers had already fled down the St. Lawrence for a last stand at Quebec City. Montgomery led about three hundred Continentals from Montreal on to Quebec City, while most of their peers raced home, enlistments complete. Only a small garrison remained in Montreal, keeping order and patrolling the city’s narrow streets between tall, gloomy stone buildings and old stone walls.

Just a month into this American occupation, King George III’s Place d’Armes bust suffered a final indignity. An unnamed author described the event in a letter extract, dated December 16, that was published in a New York newspaper a month later: “On the parade stands a holy cross, by the side of which was placed the bust of G[eorg]e W[he]lp. On the night of the 15th inst[ant] the head was severed from the shoulders and being found on the ground in the morning, was immediately carried to the hospital; but I am informed the best surgeons say they can do nothing in this case, and have pronounced the patient absolutely incurable.” The only other contemporaneous mention of the incident, recorded by Canadian arch-Patriot Thomas Walker’s wife Martha, added that the bust was then “thrown down a Privy.”[9]

A second published letter extract, originally written December 17, recounts the story almost verbatim, but with additional details—the same person undoubtedly wrote both. Neither extract identifies the author, nor do they specify who actually destroyed the bust; but they offer important clues. The second letter noted, “Captains Goforth’s and Lyon’s are stationed here.” William Goforth and David Lyon commanded two companies in the First New York Regiment. The mention of just those units while ignoring others that were present in Montreal hints strongly at the author’s identity. In Canada, Capt. William Goforth frequently wrote to regimental commander Col. Alexander McDougall, who had remained in New York. Other letters from their correspondence also appeared as unattributed extracts in New York newspapers, presumably provided by McDougall himself. Based on the published letter extracts’ identifying details, content, and even their tone, it seems quite likely that Goforth wrote them.[10]

Given the same evidence and additional background of the units mentioned, it also seems likely that some of Captain Goforth’s soldiers were responsible for destroying the bust. Their company was the only unit present in Montreal that had been originally recruited in New York City—and Manhattan had been “rocked by material violence” over the last decade. Many of that company’s men would have experienced or even participated in the episodic acts of political destruction committed by the city’s Sons of Liberty since the time of the Stamp Act crisis, and presumably some would also have seen different liberty poles torn down by redcoat garrisons in their attempts to reassert imperial power there. In the Montreal garrison, they would have been the men most inclined to demonstrate their revolutionary authority by symbolically destroying the city’s primary symbol of royal rule, showing it among garrison troops, and then disposing of the evidence to avoid discipline for their unsanctioned destruction of public property. Goforth was both an active Patriot and a fatherly officer, so he would presumably have condoned the iconoclastic episode while avoiding direct attribution to his men, for their own protection.[11]

After the monument’s destruction, the Place d’Armes kiosk remained empty until its removal fifteen years later. The discarded bust’s location remained a mystery until 1834, when workers found King George III’s well-preserved marble head in an old well shaft while excavating rue Notre Dame. The damaged art piece was given to the Natural History Society of Montreal, then later inherited by the McCord Museum.[12]

With the Montreal bust’s destruction on December 15, 1775, Continental soldiers committed a signal act of revolutionary iconoclasm almost seven months before the rebel colonies formally broke from their king. The soldiers’ premature assertion of an independent American national identity would be barely remembered, having been executed in a province that would soon be lost to their cause. The intact museum-remnant marble head of King George III simply does not hold the popular appeal held by random fragments of the monarch’s toppled New York City statue.[13]

A Pattern of Revolutionary Iconoclasm

The iconoclastic episodes in Montreal and New York happen to share a few other interesting connections. It is worth noting that Continental soldiers participated in both events—and without official orders. The Montreal iconoclasts apparently avoided any censure, but in New York a member of General Washington’s staff recorded “the Statue of George the third was tumbled down and beheaded — the troops having long had an inclination so to do, tho’t this time of publishing a Declaration of Independence, to be a favorable opportunity. The general admonished the soldiers for their overzealousness in his general orders the next morning.”[14]

Newspaper accounts provide another curious connection. The December 17 “Extract of a Letter from Montreal” commented that the bust was “of a person formerly honoured, esteemed and loved by people of all ranks, but now, like Milton’s Lucifer, alas how fall’n! how chang’d! to the reverse of what he was”—the italicized quote came from Paradise Lost. Curiously, a New York newspaper’s account of the statue destruction on the Bowling Green mentioned: “A Gentleman who was present at the ominous fall of leaden Majesty, looking back to the Original’s hopeful beginning, pertinently exclaimed, in the language of the Angel to Lucifer, “If thou be’st he; but ah! how fallen! how chang’d!” (author’s emphasis).[15]

This seemingly unusual reuse of the same Miltonian quote might have been uttered by the author of the Montreal letter (likely Goforth) or by someone who remembered the newspaper account from six months earlier, but even a seemingly chance repetition of a reference to Paradise Lost in the iconoclastic moment would not be an inconceivable coincidence. Milton scholar Lydia Schulman noted that “During the Revolutionary War, Whigs and Tories alike ransacked Milton’s epic for appropriately satanic epithets in order to portray their antagonists as ambitious, law-defying devils.” In any case, the quote’s reiteration reflects the politically-charged spirit of an influential author who exhorted “his readers to wield an iconoclastic hammer,” just as revolutionaries literally did in Montreal and New York.[16]

The destruction of the king’s New York City monument was not the beginning, nor would it be the end of revolutionary iconoclasm in the war’s first fifteen months. In late July 1776, Patriots removed and then shattered, or burned, “the coat of arms of his Majesty George III” from many government buildings in New York, Philadelphia, and several Massachusetts cities. Other unofficial signs and emblems honoring the king met similar fates. Royal Governor William Tryon observed: “every vestige of Royalty, as far as has been in the power of the Rebels, done away.” Such acts of destruction served to physically reinforce the ideological termination of monarchical rule expressed by the Declaration of Independence.[17]

Iconoclasm historian David Freedberg described the revolutionary ethos of such moments: “The aim is to pull down whatever symbolizes—stands for—the old and usually repressive order, the order which one wishes to replace with a new and better one.”[18] Over the centuries, the destruction of New York’s King George III statue—represented in illustrations, reenactments, commemorations, and museum exhibits—has stood as the most enduring image of that spirit in the American Revolution. Yet the fate of the king’s Montreal bust, as well as the destruction of other symbols of royal authority in late July 1776, make it clear that the famed New York Bowling Green episode was just one in a series of politically iconoclastic episodes early in the war—with precedents of demonstrative vandalism and destruction occurring well before the Declaration of Independence—and in Canada of all places.

[1]Wendy Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment (University Park: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), 4, 5. For more on the New York event, see Bob Ruppert, “The Statue of George III,” Journal of the American Revolution (September 8, 2014) https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/09/the-statue-of-george-iii/; Arthur S. Marks, “The Statue of King George III in New York and the Iconology of Regicide,” The American Art Journal, 13 (1981), 61-82.

[2]Quebec Gazette, May 30, 1765; [Jonas Hanway], Motives for a Subscription Towards the Relief of the Sufferers at Montreal in Canada (London, 1766); Joan M. Coutu, Persuasion and Propaganda: Monuments and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 182, 184; Joan M. Coutu, “Philanthropy and Propaganda: The Bust of George III in Montréal,” Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 19, no. 1-2 (1992): 61; Cynthia A. Kierner, Inventing Disaster: The Culture of Calamity from the Jamestown Colony to the Johnstown Flood (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 99-100, 119; M15885, Head from a Bust of George III, 1765, McCord Museum, collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artifacts/M15885.

[3]Quebec Gazette, September 22, 1766.

[4]E. Z. Massicotte, “Réponses: Un Buste De George III à Montréal,” Bulletin des Recherches Historiques 21 (1915), 184; November 17, 1775, “The Journal of Major Henry Livingston of Third New York Continental Line August to December 1775,” Gaillard Hunt, ed., The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 22 (1898): 28-29; Alan Gordon, “Contested Terrain: The Politics of Public Memory in Montreal, 1891-1930,” Ph.D. thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, 1997, 129; October 11, 1773 (summary), “Lettres de M. Etienne Montgolfier, Grand Vicaire, à M. Olivier Briand, Vicaire Général du Diocèse de Québec de 1761-1775,” Rapport de L’Archiviste de la Province de Québec Pour 1947-1948, 94; Vers en bouts rimés, à l’occasion du Buste du Roi . . .,Quebec Gazette, October 14, 1773.

[5]Extract of a letter to Guy Carleton, April 7, 1775, Kenneth Davies, ed. Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783 (Dublin: Irish University Press, 1975), 9:93.

[6]“Intercepted Letter, Montreal, May 6, 1775,” Connecticut Gazette (New London), June 16, 1775; Simon Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire de l’Invasion du Canada par les Bastonnois: Journal de M. Sanguinet,” and Pierre Guy to François Baby, May 1, 1775, in Hospice-Anthelme Verreau, Invasion du Canada: Collection des Mémoires Recueillis et Annotes. (Montréal: Eusèbe Senécal, 1873), 24, 305. Former Quebec attorney general Francis Maseres published an account in England adding that the bust was topped with a bishop’s mitre, a detail not present in Montreal reports, Francis Maseres, Additional Papers Concerning the Province of Quebeck . . . (London, 1776), 155.

[7]Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire,” 24; Extract of a Letter to [Guy Carleton], May 4, 1775, Davies, Documents of the American Revolution, 9: 123; Maseres, Additional Papers, 155-56, 163-65; “Intercepted Letter, Montreal, May 6, 1775,” Connecticut Gazette [New London], June 16, 1775.

[8]“By His Excellency Guy . . . A Proclamation [May 8, 1775],” Quebec Gazette, May 11, 1775. Some historians have erroneously blamed American soldiers for the May 1 vandalism, but the Continental Northern Army would not enter the city for another six months.

[9]“Extract of a letter from Montreal, Dec. 16.,” The Constitutional Gazette (New York), January 17, 1776; Silas Ketchum, ed., The Collections of the New Hampshire Antiquarian Society No. 2, The Shurtleff Manuscript, No. 153. A Diary of the Invasion of Canada, 1775 . . . Written by a Mrs. Walker (Contoocook, NH: 1876), 35. Martha Walker’s account mistakenly reported that the destruction happened “soon after” the bust was defaced on May 1.

[10]“Extract of a letter from Montreal, dated December 17,” New-York Journal, January 18, 1776. Extant Goforth-McDougall correspondence is captured in Mark R. Anderson and Teresa Meadows, The Invasion of Canada by the Americans, 1775-1776: As Told through Jean-Baptiste Badeaux’s Three Rivers Journal and New York Captain William Goforth’s Letters (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016); Goforth’s February 22, 1776 letter to Benjamin Franklin shares a similarly playful tone; 74-78. Of the other companies in Montreal at the time, Lyon’s originated in northeast New Jersey, while Henry B. Livingston’s, Joseph Benedict’s, and David Palmer’s companies of the Fourth New York Regiment were recruited in Dutchess County.

[11]Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York, 4-5, 19, 28-29, 91-92. The author’s desire to avoid attribution would explain the unusual third-person reference to the companies present in Montreal, mentioned above.

[12]Pierre-Georges Roy, “Réponses,” Bulletin de Recherches Historiques 8 (Janvier 1902), 24-25; Massicotte, “Un Buste De George III à Montreal,” 184; Edgar A. Collard, “Throwing a Statute Down a Well, Montreal Gazette, December 3, 1945; M15885, Head from a Bust of George III, McCord Museum.

[13]Coutu, Persuasion and Propaganda, 233.

[14]Journal of Samuel Blachley Webb, Worthington C. Ford, ed., Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb (New York: 1893), 1:153; Head-Quarters, New-York, July 10, 1776, Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Fifth Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1853), 1:225.

[15]“Extract of a letter from Montreal, dated December 17,” New-York Journal, January 18, 1776; “New-York, July 11,” New-York Journal, July 11, 1776; John Milton, Paradise Lost (1674), vol. 1, line 84.

[16]Schulman, Paradise Lost and the Rise of the American Republic, 9, (quote) 14; (“his readers . . .”) Simpson, Under the Hammer, 105. Goforth was in New York at the time and lived only a few blocks from the Bowling Green.

[17]“New-York, July 25,” New-York Journal, July 25, 1776; Ebenezer Hazard to Horatio Gates, July 12, 1776, and Governour Tryon to Lord George Germaine [sic], August 14, 1776, Force, ed., American Archives, Fifth Series, 1: 227, 949; “Watertown, July 22,” Boston Gazette, July 22, 1776; “Worcester, July 24,” Massachusetts Spy (Worcester), July 24, 1776.

[18]David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 389-90.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...