Constant Avery of Eaton, in New York’s Madison County, travelled sixteen miles to the county seat in Wampsville in the first week of October 1832. On October 8 he appeared in open court to apply for a federal pension for his years as a soldier in the Continental Army. Avery was “aged seventy three years on the fourteenth day off November last,” which indicates he was born in 1758. Originally from Groton, Connecticut, Avery didn’t move to Eaton until 1798, where he raised his family. Luckily for historians, Constant Avery delivered a brief but detailed account of his services during the American Revolution that 1832 day in Madison County—one of danger, battles faced, and long periods of travel.[1]

Constant Avery appears on a roll for Captain Gallup’s company of militia on October 31, 1776, but as it offers no detail, we can extract little from this. If in fact this is the same Avery, he made no mention of it in his pension application, preferring to date his start in the service as “the third day of February in the year 1777,” which muster rolls confirm. Avery enlisted under “Lieutenant Stephen Billings of Groton . . . in Col. Herman Swift’s regiment,” the 7th Connecticut, in his home town, with about “fourteen others that were enlisted by said Billings at the same time & place.” They were then marched the twenty-five miles to “Killingsworth . . . & there joined the [remainder] of the men who made up the company,” which was made up of men from those two towns. When they arrived, the company fell under the command of Capt. Aaron Stephens of Killingsworth. Finally the company “joined the regiment at New Milford” before marching to Peekskill, New York, where they joined the “Brigade commanded by General [Jedediah] Huntington.” It is not clear precisely when Avery’s contingent arrived in Peekskill, but Brig. Gen. Alexander McDougall wrote Gen. George Washington on April 17, 1777 to say that there were “about 140 Men here of Col. Swift and Col. Shepherd’s regiments, some without Arms, others have not had the small Pox. Shall the former go on without, and the latter before they are innoculated?” Avery didn’t specify that he received inoculation at this time, so it is plausible that he had already been exposed to the virus.[2]

As Avery settled into military life, he soon found an exciting assignment when “the summer after his enlistment there was a call for men to man the shipping on the North [Hudson’s] River.” Avery “turned out to make up the number of men to man the shipping under Capt. Chamberlain,” likely Ephraim Chamberlain, a lieutenant in the 7th Connecticut. The men were “divided among the vessels as marines & he . . . went aboard a Row Galley called the Shirk [Shark]. This vessel cruised up & down the River as a guard vessel, until Genl [Sir Henry] Clinton came up the River to meet Burgoine at Albany.” In an attempt to link up with British Gen. John Burgoyne above Albany, Gen. Sir Henry Clinton sailed up the Hudson from New York City, arriving at Verplanck Point just south of Peekskill on October 5, 1777. The next day, they crossed over to the landing of King’s Ferry at Stony Point on the western shore of the river and marched north to assault the twin forts along to Popolopen Creek, Forts Montgomery and Clinton.

Avery remembered that Clinton “landed his army at Kings Ferry close by Stony Point & went up [the] East side of the River & burnt the Continental Barn called the Continental Village & then recrossed the River & marched up & attacked & took Forts Montgomery & Clinton.” As the British troops marched over Dunderberg Mountain on the densely foggy morning of October 6, the British shipping sailed north. At Fort Montgomery, a chain and ship’s cables had been stretched across the river to Anthony’s Nose; the American vessels were riding north of it, awaiting the approach of the enemy vessels. Avery recalled that his “little fleet lay above the chain to guard it & prevent the British shipping from coming up—our little fleet consisted of the ship Montgomery, one Sloop & two Gallies.” In this recollection, Avery was absolutely correct. The vessels that took part in the battle were the frigate Montgomery, the galleys Shark (Avery’s) and Lady Washington, and the sloop Camden.[3]

When the British galleys pulled into view, the battle began. The British galley Dependence fired nearly 100 rounds from its twenty-four pounders and more from its six pounders. The commander of the frigate Montgomery held her fire until she was struck, and then the American vessels opened up. As the battle raged on, more British vessels came up, and the forts were stormed. There was little else to do, so the American ships rescued as many from the forts as they could. After dark, with poor winds, and the tide against them, it was decided to burn the vessels, except for the Camden, which had run aground. Avery lost his first battle when “the enemy took the forts & then the admiral hailed & told us to make our way up the River—We lost all our vessels,” except the Lady Washington. Some men transferred “aboard her & manned her out.”[4]

Over the next ten days, the British (after having dismantled the chain) sailed north, with the Americans beating a retreat for much of the way. On October 16, their fleet arrived off of Kingston, at the time the capital of New York. Here was more action for the almost nineteen year old Avery, for “as the enemy come up, we rowed our vessel [the Lady Washington] out & changed many shots with [the enemy] until [they] began to land.” Overwhelmed, the Lady Washington was “ran up Esopus Creek [present Rondoubt Creek] about two miles & sunk our Vessel.”

The vessel that Lady Washington exchanged shots with was once again the galley Dependence. Dependence’s journal recorded that “at ½ past 10 AM the Rebles began to Cannonade us from their Battery at the mouth of Esopus Creek, fired 9 . . . shot at the Battery and Reble Galley that were playing on us.” Lady Washington was “scuttled . . . near Eddyville,” a small village about two miles from the mouth of the Rondoubt. As Kingston burned, Avery and the crew stood on dry land and “marched out to the town of Hurley.” While in Hurley, Constant Avery witnessed one of the more unique points of Clinton’s expedition up the Hudson. Following the British victory at Forts Montgomery and Clinton, a runner was sent to Burgoyne with a message in a hollow silver musket ball. The runner, Daniel Taylor, was captured and swallowed the bullet. Given an emetic, which “had the desired effect; it brought it from him,” that is, he vomited up the bullet. He was soon convicted of being a spy and sentenced to hang. Too busy with having fought the British twice in one month, Avery merely noted that a“spy hung on an apple tree, who swallowed the Bullet.”[5]

After an exciting October, Avery recalled that “we went to Valley Forge & joined our Brigade & wintered at that place.” Though he wrote nothing of that winter, muster rolls prepared in December 1777, January and February 1778 mention that he was almost continuously “on command,” though we unfortunately have no details of what he was doing in this service. Avery, back with his 7th Connecticut Regiment “lay at Valley Forge until the British left Philadelphia in the month of June 1778 & the whole army was then advanced to march to obstruct the passing of the enemy & an engagement took place at Monmouth, New Jersey.” Recalling the length of that action on June 28, 1778, Avery said “the Battle lasted until night.” As Huntington’s Brigade lay on Perrine’s Ridge, but otherwise played no major role in the action (though the afternoon cannonade must have been unnerving), Avery moved on to say that the army “marched back to the North River” crossing at King’s Ferry and participating in the White Plains encampment. Here he was listed as “on duty” in August, but he had little else to comment on. By October, he had marched to New Milford, Connecticut, and from thence to “Reading, Connecticut & there took up winter quarters.”[6]

Avery’s winter was again left without comment, but his musters indicate that he was “on command” in February 1779, “on command” in New London in March, and “on command” in Reading (their encampment had switched to Crompound) in April. The first day of May brought a change to Constant Avery, as he was transferred to his regiment’s light infantry company commanded by Capt. Ephraim Chamberlain, “in the spring of the year 1779.” Continuing, he said, “we marched back to the vicinity of [the] Hudson River & then the third campaign opened.” Then, “there was a call for men out of each company of the Brigade to make up a company of [Light] Infantry under Captain Chamberlain, to go onto the lines, next to the enemy.” This was the same Chamberlain who Avery had served under on the Hudson in 1777. When they had formed into a Corps of Light Infantry by joining with other similar companies, “we lay . . . stationed on the ground [where] Old Fort Montgomery was & was engaged night and day in patrolling & scouting.” As a Connecticut soldier, Constant Avery was assigned to the 3rd Light Infantry Regiment, commanded by Col. Return Jonathan Meigs.

On the first day of June 1779, the British had completed their conquest of King’s Ferry, which consisted of Stony Point on the west of the Hudson and Verplanck Point on the east. The taking of this vital ferry crossing not only interrupted communications, but also threatened the young but strong post of West Point, only eleven miles north. Consequently, Washington moved the Main Army around West Point in a massive arc from Smith’s Clove in the Ramapo Mountains to the area around Mandeville’s, today’s Garrison, New York. As part of this shift, the Corps of Light Infantry was formed and detached to the new front at the ruins of Fort Montgomery, and placed under the command of Brig. Gen, Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania.[7]

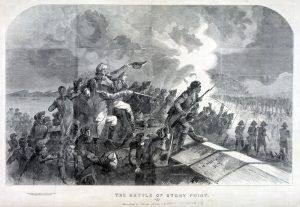

Generals Washington and Wayne spent early July creating a plan of attack: King’s Ferry had to be retaken. The British fortifications at Stony Point would have to go first—as the higher ground, it’s guns could be turned on lower Verplanck to pound it into submission. The Corps of Light Infantry would assault Stony Point in three columns. From the north, Col. Richard Butler’s 2nd Light Infantry Regiment would cross the swamp surrounding the point. Detaching from them and providing a demonstration in the middle would be a combined Massachusetts and North Carolina detachment under Maj. Hardee Murfree. The main assault, in which Avery would be, was to come through the swamp on the south and into the river to flank the works. This column was commanded by Col. Christian Febiger and accompanied by Wayne himself. Unlike the feint in the middle, the flanking columns would be strictly forbidden to fire a shot; their dependence being entirely on the point of the bayonet. As Avery proudly recalled, “Capt. Chamberlain’s company was in the detachment from the American Army that made the attack upon & took Stony Point under General Wayne.” The assault was planned for midnight on the morning of July 16, 1779. Avery “was in the company at the time of the attack & assisted in taking the fort at the point of the bayonet. Not a gun was fired on the part of the Americans,” excepting Murfree’s feint. The British commander “whose name he thinks was Johnson was mortally wounded.” Lt. Col. Henry Johnson of the 17th Regiment of Foot quite survived the battle but was taken prisoner with the rest of his garrison. While there was a flurry of activity in the next few days, Avery made no mention of it in his pension application. All he said was that “after the taking of Stony Point, we marched back to the old ground & soon after joined our Brigade & went into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey.”[8]

Avery recalled correctly; after Stony Point, the Light Infantry returned to their training grounds at Fort Montgomery. In August 1779, Avery left the Light Infantry and was returned to his company in the line of the 7th Connecticut. No reason was given, but top performance was expected of the Light Corps, so any number of maladies might have instigated his switch back to his original company. September muster rolls have Avery back with his regiment at Nelson’s Point, opposite West Point and just south of Constitution Island. The remainder of Avery’s autumn, according to muster rolls, was uneventful. December 1779 and January of 1780 show the 7th Connecticut in New Jersey for the winter, specifically “Morristown . . . [where he] was discharged at that place after having served for three years on the Continental Establishment. He was discharged about the month of February 1780.” According to muster rolls, February 2, 1780 was the last day of Avery’s service.[9]

All indications point to Avery returning home to Groton after his enlistment. In 1781, forces under ex-Continental officer Gen. Benedict Arnold sailed up the Thames River and went ashore at New London and Groton. British troops famously attacked Fort Griswold in Groton on September 6, 1781. Many Averys of Groton fought and were harmed in that battle, but Constant was inexplicably not among them. His next appearance on the historical record was his marriage to Zipporah Williams at Groton in 1796. He moved to New York two years later. Constant Avery died on February 7, 1844 in Eaton, New York. Unfortunately, his activities after his military service are unrecorded, but luckily he left us an extensive tale of his time during the American Revolution.[10]

[1]Pension Application of Constant Avery, W.1696, www.fold3.com/image/11077910; Elroy McKendree Avery and Catharine Hitchcock (Tilden) Avery, The Groton Avery Clan, Vol I, (Cleveland: no publisher listed, 1912), 289.

[2]Constant Avery Muster Roll, Gallup’s Company, www.fold3.com/image/17153431; Pension of Constant Avery; Alexander McDougall to George Washington, April 17, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0173.

[3]Avery Pension; Ephraim Chamberlain Muster Roll, September 1777, www.fold3.com/image/17162538. Chamberlain is listed “on Comd,” indicating he was doing other duty and very well may have been aboard the shipping; The Naval Battle of Fort Montgomery, Interpretive Sign, New York State OPRHP/Fort Montgomery State Historic Site; Constant Avery Muster Roll, September 1777, fold3.com/image/16247820.

[4]The Naval Battle of Fort Montgomery; Avery Pension.

[5]Journal of H.M. Galley Dependence, October 16, 1777, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Michael J. Crawford, ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996), 10:183; “The Lady Washington Galley,” Olde Ulster Magazine, Vol IX, No 10 (October 1913), 306; Daniel Taylor’s musket ball message from Clinton to Burgoyne read: “Nous y voici, and nothing now between us but Gates. I sincerely hope this little success of ours may facilitate your operations. In answer to your letter of the 28th of September by C. C. I shall only say, I cannot presume to order or even advise, for obvious reasons. I heartily wish you success. Faithfully yours, Clinton.” The Spy and the “Guard” House: October 16, 1777, through December 18, 1777, Hurley Heritage Society, www.hurleyheritagesociety.org/history/spy-and-guard-house/; Daniel Taylor the Spy Sentenced to Death, 14 October 1777, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795-1801-1804(New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford, 1900), 2:443; Avery Pension.

[6]Avery Pension; Constant Avery December 1777 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/16247826; Constant Avery January 1778 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/16247850; Constant Avery February 1778 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/16247851; Avery August 1778 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/16247861; Avery October 1778 Muster Roll, fold3.com/image/16247865; For information on Huntington’s Brigade at the Battle of Monmouth, see Mark Edward Lender and Gary Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017).

[7]Constant Avery Muster Roll February 1779, fold3.com/image/16247891; Avery Muster Roll March 1779, fold3.com/image/16247893; Avery Muster Roll April 1779, fold3.com/image/16247895; Avery Muster Roll May 1779, fold3.com/image/16247897.

[8]Enclosure: Plan of Attack, July 15 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0416-0002; Avery Pension; Constant Avery Muster Roll July 1779, fold3.com/image/16247902.

[9]Avery Muster Roll August 1779, fold3.com/image/16247904; Avery Muster Roll September 1779, fold3.com/image/16247908; Charles H. Lesser, Ed., Sinews of Independence: Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 144, 148; Avery Muster Roll January 1780, fold3.com/image/16247920.

[10]Avery, The Groton Avery Clan; Find A Grave, Constant Avery (1758-1844), www.findagrave.com/memorial/32760255/constant-avery.

3 Comments

This fascinating account is slightly marred by the painting at the beginning: it shows the various galleys rigged the same way that Arnold’s galleys were rigged on Lake Champlain. The hulls of the galleys were identical to the galleys on Lake Champlain, but we know from a powder-horn view of the galley Lady Washington that she was rigged as a topsail schooner (similar to the schooner Royal Savage on Lake Champlain), and presumably the other river galleys were also so rigged. The painting is otherwise beautiful. You can see the powder-horn engraving in my 1986 out-of-print book Early American ships.

Be cautious about making such a presumption. The topsail-rigged galley might have been carved on the horn because it was unusual. In addition, while Arnold’s fleet is probably the best known example, lateen rigging appeared in other locations and times. Compared to topsail rigging, lateen is quicker and cheaper to produce, easier to operate, and able to run quite close to the wind if need be–the latter two qualities making it perfect for the narrow confines of a river or lake where moving to windward can be a challenge. It would seem like there must be other sources out there that document what type of rigging these ships received.

Hi John – Peter here from Fort Montgomery State Historic Site. A google search for the powderhorn you mentioned proved fruitless. Do you have a pic you could post or email? We’d be interested in any original depiction of the Lady Washington! Thank you for any help or information. Your book sounds interesting.