Since James Thomas Flexner’s 1974 Pulitzer recognition for his biography of George Washington, one of the axioms of the American founding is that the general, George Washington, was the “indispensable man.”[1] The selection, therefore, of Washington as the commander of the Continental Army was undoubtedly among the most critical decisions in the history of the war—perhaps indeed even in the history of America.

Historian Jeff Dacus provides evidence that “various behind-the-scenes” negotiations preceded Washington’s nomination. In the end, however, “There is no record how the delegates were ‘persuaded’ to vote for Washington,”[2] concludes Dacus. There is, however, compelling evidence pinpointing how the delegates were persuaded to vote unanimously for Washington, evidence that reveals an even larger phenomenon that may have permeated the entire Revolution.

Perhaps the most important clue concerning what persuaded the delegates to choose Washington comes from the hand of Washington himself. Writing to officers in Virginia five days after his appointment as general, Washington explained, “I am called by the unanimous voice of the Colonies to the command of the Continental army.”[3] He observed that the choice was the result of “the partiallity of the Congress however, assisted by a political motive.” What was the “political motive”? Historian Paul K. Longmore dilated upon Washington’s remark: “Congress selected him to command the Continental Army, said Washington, because of ‘partiality . . . assisted by a political motive.’” The “political motive” was undoubtedly the intent to allay regional “jealousy” and to promote continental unity.[4]

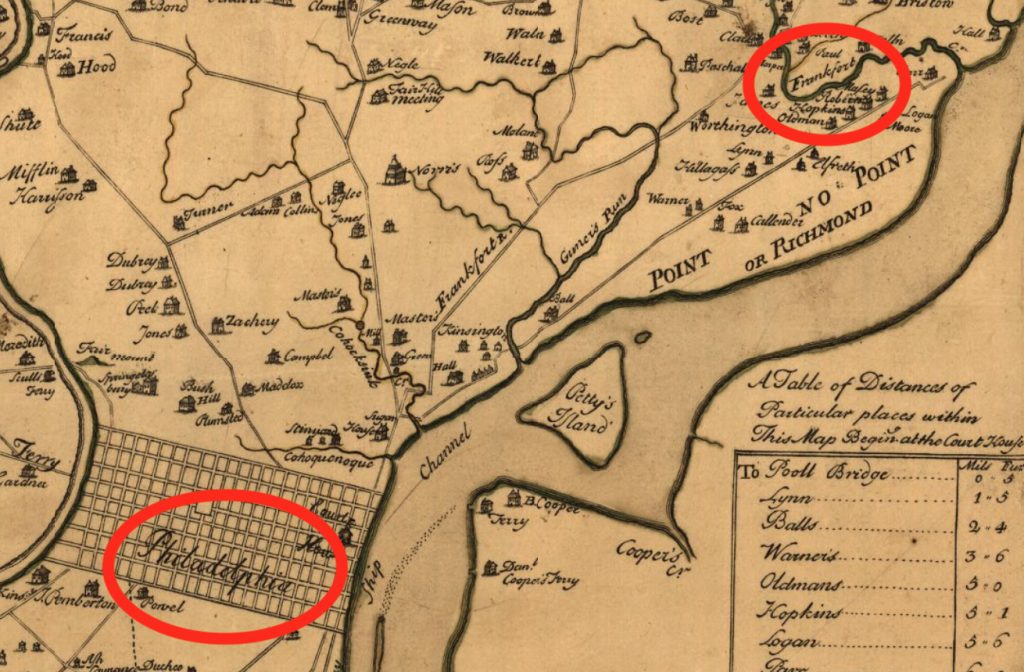

Longmore’s observation is entirely in accord with the detailed narrative of John Adams. According to Adams, the decision to appoint Washington as commander in chief was deliberate and calculated, and part of a scheme conceived the previous year in the small village of Frankford, Pennsylvania. Adams referred to the scheme as “the Frankfort advice.” “Without it,” wrote Adams, “Mr: Washington would never have commanded our armies.”[5] That is quite a bold claim, and very worthy of analysis and consideration. If it is an accurate statement, it is one of the most crucial dominoes in the emergence of the “indispensable man,” and subsequently in the history of the United States.

The Frankford Advice had little, if anything, to do with Washington’s experience or military skill. Instead it had everything to do with the state of his nativity, Virginia. In short, the Frankford Advice was to, as Adams put it, “place Virginia at the head of everything.” According to Adams, the Frankford Advice not only resulted in the appointment of Washington as military commander, but also resulted in Richard Henry Lee making the motion to declare independence, Thomas Jefferson authoring the Declaration of Independence, Samuel Chase making the motion to seek foreign alliances, and Thomas Johnson nominating George Washington as military commander.[6]

Adams represented the Frankford Advice as pivotal to the entire cause of America, and asserted that it permeated, “the whole policy of the United States”[7] from 1774 through 1822. Why is it, then, that the phrase “Frankford Advice” does not ring very familiar as one of the essential vocabulary terms relative to understanding the Revolution? Surprisingly no scholarly attention has been given heretofore to the Frankford Advice, per se.

Where and When did the Frankford Advice Originate?

After the King and Parliament passed the notorious “Intolerable” Acts in 1774, colonial leaders agreed to convene in Philadelphia to confer regarding the colonists’ options moving forward. This meeting was known as “The First Continental Congress.” The four Massachusetts leaders who traveled together to Philadelphia to attend the congress included the Adamses, John and Samuel; Thomas Cushing, and Robert Treat Paine. When these four men from Massachusetts reached the outer perimeter of Philadelphia on August 29, 1774, they were deliberately intercepted by a significant delegation of colonial leaders from Pennsylvania and elsewhere. This encounter occurred in the village of Frankford, six miles north of downtown Philadelphia. Those who came out to intercept the Massachusetts delegates felt it was essential to confer privately with them before they mingled with all the delegates in town, particularly the delegates from Virginia. John Adams, who at that time was traveling to Philadelphia for the first time in his life,[8] listed the following names in the deputation that intercepted their carriage at Frankford:

John B. Bayard

Benjamin Rush

Thomas Mifflin

Thomas McKean

John Rutledge

John Sullivan

Nathaniel Folsom

and “a Number of Gentlemen, the most active Sons of Liberty, in Philadelphia”[9]

In 1822, John Adams wrote to Timothy Pickering expanding upon the encounter with these men at Frankford: “We invited them to take Tea with us in a private apartment. They asked leave to give us some information and advice.”[10] This August 29, 1774 meeting of a minimum of thirteen men was the extent of the Frankford conference, but if this fateful short meeting had not happened, the trajectory of the Revolution may have been very different, according to Adams.

Exactly where in Frankford the meeting took place has not been determined. A Philadelphia historian and expert, Harry Kyriakodis, wrote an unpublished article in 2011 in which he attempted to identify the location. Kyriakodis conjectured, “The tavern was very likely the Jolly Post Inn, which was once located on the west side of Main Street (Frankford Avenue) just north of Orthodox Street.”[11] This conjecture is a likely a result of misreading Adams. In his Diaryof August 29, 1774, after recording the Frankford conference, Adams wrote, “We then rode into Town, and dirty, dusty, and fatigued as we were, we could not resist the Importunity, to go to the Tavern, the most genteel one in America.”[12] The “town” referenced in this sentence is actually Philadelphia, not Frankford, as Adams said they were met at that tavern by many others and welcomed to Philadelphia.

In his letter to Timothy Pickering in 1822, Adams referred to the location of the Frankford conference as “a private apartment,”[13] not a tavern. Perhaps Kyriakodis believed that the private apartment was a reference to a tavern, but it seems more likely that he mistook the “genteel” tavern in Philadelphia as a reference to the Frankford conference location. Jack McCarthy, another Philadelphia historian, similarly conjectured in 2011

Unfortunately, we don’t know where in Frankford this critical meeting took place, as there is no mention of the exact location in the historical record. Most likely, it was in one of the two main taverns in the village at that time: the Jolly Post Inn, which was located at the northwest corner of what is now the intersection of Frankford Avenue and Orthodox Street, or McVeagh’s Tavern, also known as the Old Inn, located near the current Womrath Park at Kensington and Frankford Avenues.[14]

McCarthy did not provide any citations for this conjecture. At this point, it appears that no researcher has found evidence for, nor deduced the precise location of the apartment where the fateful Frankford conference of August 29, 1774 occurred.

The Rationale of the Frankford Advice

At a private apartment in Frankford, Pennsylvania, John Adams and his three companions from Massachusetts sat down and had tea with at least nine other Whiggish leaders of the colonies. These nine or more men who rode out to Frankford asked to give the Massachusetts delegation some advice, and the Massachusetts men were eager to receive it. First, they relayed that all four travelers from Boston were notoriously reputed to be radicals, set on American independence. Consequently they warned them, “you must not utter the word Independence, nor give the least hint or insinuation of the idea, neither in Congress or any private conversation; if you do you are undone.”[15] That was the first prong of the Frankford Advice.

The second and more impactful prong was that in the upcoming congresses in Philadelphia, Massachusetts should defer to Virginia in all things.

you must not pretend to take the lead. You know Virginia is the most populous State in the Union. They are very proud of their antient Dominion, as they call it; they think they have a right to take the lead, and the Southern States and middle States too, are too much disposed to yield it to them.

Their advice included a reminder of Virginia’s history and culture. The reference to the “antient dominion” alluded back to the Virginia House of Burgesses’s self-assessment in the late seventeenth century. In 1697, Virginians referred to themselves as “his majesty’s most ancient colony & dominion of Virginia.”[16] Indeed, since the time when the first English people set foot upon Jamestown in Virginia and Plymouth in Massachusetts, the former had been proud subjects of the British Crown while the latter had been at odds with the Crown from the start, primarily on religious grounds.

The Frankford advisors proceeded to remind the men from Massachusetts that their colony had been embroiled in disputes with London for quite some time, but Virginia might not be eager to be lured in by the zeal of the Bostonians:

you are the Representatives of the suffering State. Boston and Massachusetts are under a rod of Iron. British fleets and Armies are tyrannizing over you; you yourselves are personally obnoxious to them and all the friends of government. You have been long persecuted by them all:—Your feelings have been hurt; your passions excited; you are thought to be too warm, too zealous, too sanguine, you must be therefore very cautious. You must not come forward with any bold measures.

Indeed, the bulk of the American violence which had ensued between colonials and the King’s representatives, such as the March 1770 “massacre,” had taken place in Boston. Yet every Whig there at Frankford knew that their only hope of ultimate success in the American contest with the Crown required them to gently coax the Virginians to rally behind them. That was the rationale of the Frankford Advice.

The specific strategy that the men from New England were advised at Frankford to employ at the congress in Philadelphia was to “place Virginia at the head of everything.”[17] Since Virginians took great historic pride in being leaders, the Frankford Advice was to do everything possible to give the Virginians the impression that they were the true leaders and instigators of revolution. The goal was to induce Virginians into believing that resistance to the Crown, indeed even independence, was an endeavor of their own design. The most effective way to do this was to make sure that Virginians’ voices would be given deference in Congress and that they would hold the most important leadership roles moving forward. John Adams, his cousin Samuel, Robert Treat Paine, and Thomas Cushing thought this advice to be brilliant. In his letter to Pickering, Adams praised the wisdom given them at Frankford:

This was plain dealing, Mr Pickering, and I must confess, that there appeared so much wisdom and good sense in it, that it made a deep impression on my mind, and it had an equal effect on all my Colleagues.

Indeed, the “good sense” of the Frankford Advice is fundamentally the same strategy advocated by some of the most noteworthy consultants, coaches, and influential leaders in modern times. For example, it was recommended by Dale Carnegie in How to Win Friends and Influence People. Carnegie’s 7th Rule was: “Let the other fellow feel that the idea is his.” Nelson Mandela recommended the strategy of “leading from the back,” which he reportedly gleaned from the wisdom of Abraham Lincoln. Mandela quoted Lincoln’s advice, “It is wise to persuade people to do things and make them think it is their own idea.” Even today this strategy continues to be touted among business experts. Douglas Van Praet, a leading expert in behavioral science and marketing, writes, “If you want someone else to completely believe in your idea, you must make them believe that it was their own idea all along.”[18]

Yet long before any of these famed experts on leadership touted it, Adams and his advisors employed the psychological cleverness of this strategy. Shortly after the Frankford conference in 1774, John Adams confidentially explained the unfolding of the Frankford strategy to William Tudor of Boston: “We have been obliged to keep ourselves out of Sight, and . . . to insinuate our Sentiments, Designs and Desires by means of other Persons.”[19] Historian John C. Miller described how the strategy played out during the First Continental Congress:

The New England delegates, who had been expected to roar like lions, proved meek as lambs. At the meetings they were so quiet and unobtrusive that they seemed to have come to Philadelphia solely to enjoy the peace and restful surroundings of the City of Brotherly Love . . .While the New Englanders discreetly remained in the background the Virginians and Carolinians stepped forward as champions of the patriot cause.[20]

This is a clear testimony to the successful execution of the Frankford Advice. The Massachusetts delegates shut their mouths and ended up orchestrating the Revolution like ventriloquists “by means of other Persons.”[21] Small wonder that it was implemented by the Massachusetts delegates so effectively.

Implementation of the Frankford Advice

According to Adams’ narrative, the Frankford Advice was implemented on multiple occasions in Congress; most prominently, when the time came for Congress to select a military commander. Adams detailed how he implemented the Frankford Advice in June 1775 when several gentlemen’s names were nominated as general in chief of the Continental Army. The nominees included two residents of Adams’ home state, John Hancock and Artemas Ward.[22] Adams admitted that his own natural inclination was toward Ward, whom he described as an intimate friend “who had known him at school, within two doors of his father’s house.”[23] Ward was also initially the favorite of the majority of the members of the Continental Congress.[24] Adams also knew that his countryman, John Hancock, wanted the appointment and was fully anticipating Adams’ support for his nomination.[25]

Appointing either Ward or Hancock as commander, however, would contradict the Frankford Advice. So, Adams was willing to risk giving offense both to Ward and Hancock for the sake of courting Virginia. Given the divisions that existed among the members, the vote was postponed for an extra day, giving Adams opportunity to work behind the scenes to persuade the members on behalf of Washington.[26] The people Adams mostly had to convince were his own “best Friends”[27] from New England who, like Adams, believed Ward should be chosen. Adams recalled, “I had no other Way to soften their hard thoughts, but by appeals to their Patriotism; by urging the Policy and necessity of sacrificing all our feelings to the Union of the Colonies.” That sacrificial “policy” Adams urged was the Frankford Advice. This was the “behind-the-scenes” machination that illuminates Dacus’s article.

Artemas Ward’s biographer, Charles Martyn, noted that the reason Ward was passed over for Washington was “neither the feeling of any imperative need for Washington as commander-in-chief, nor any dissatisfaction with Ward. It is a matter of deference to Virginia.”[28] Deference to Virginia was the essence of the Frankford Advice. Adams explained the case he put forth when he stood to endorse Washington:

I had no hesitation to declare that I had but one Gentleman in my Mind for that important command, and that was a Gentleman from Virginia who . . . would command the Approbation of all America, and unite the cordial Exertions of all the Colonies better than any other Person in the Union.[29]

As he adhered to the Frankford Advice in this instance, Adams observed John Hancock’s reaction:

When I came to describe Washington for the Commander, I never remarked a more sudden and sinking Change of Countenance. Mortification and resentment were expressed as forcibly as his Face could exhibit them.[30]

Adams later relayed that many others in New England “subjected” him to “bitter exprobrations for creating Washington Commander in chief.”[31]

When Washington himself explained his appointment as a product of “a political motive,” it is beyond reasonable doubt that he was commenting on the way he observed the Frankford strategy in action during the delayed vote. This is the only way to explain Adams saying “he [Washington] knew it” in an 1815 letter reflecting on the unfolding of the Frankford Advice. “Washington was the Creature of a Principle; and that principle was The Union of the Colonies. He knew it,” remarked Adams, and smugly added, “Virginia is indebted to Massachusetts for Washington.[32] It is difficult to read the words “indebted to Massachusetts” and not hear the implication, “indebted to me, John Adams as I implemented the Frankford Advice.” Yet if Adams’ version is accurate, perhaps he had warrant to set the record straight.

That the choice of Washington was truly a product of the Frankford Advice is evidenced by another member of Congress’ commentary on the appointment. Two days after the decision, Eliphalet Dyer of Connecticut praised the way Washington “more firmly Cements the Southern to the Northern and takes away the fear of the former.”[33] The collective contemporary evidence is strong supporting Adams’ assertion that Washington’s rise to the top of the heap was a product of the Frankford Advice.

Thomas Jefferson as Author of the Declaration

According to Adams, Thomas Jefferson’s role as author of the Declaration of Independence was likewise due to the Frankford Advice. He told Timothy Pickering in 1822,

You enquire why so young a man as Jefferson was placed at the head of the Committee for preparing a declaration of Independence? I answer, it was the Frankfort advice, to place Virginia at the head of everything.[34]

The accuracy of Adams’ 1822 recollection of this event has been called into question.[35] To some historians, Adams’ version is revisionist and self-aggrandizing. It is alleged to be the product of a fragile ego feeling overshadowed by others. The psychological analysis of Adams’ account of the Frankford Advice is that it allowed Adams to imply that Jefferson would not have risen to his iconic status if not for Adams deliberately yielding the spotlight.

The most formidable scholarly psychological treatment in this regard is by historian Robert E. McGlone, who argues that Adams’ 1822 account was revised to establish himself as “the real author of American independence.” McGlone dilates upon mistakes and errors in Adams’ recollection to prove the assertion that “memory failed the old man.”[36]

Without responding to each premise in McGlone’s argument, there is one glaring problem with his article that seriously undermines his case. McGlone’s gives the following account of the Frankford Advice:

Adams referred to the strategy of deferring to Virginians as the “Frankfort advice.” At a meeting in Frankfort, New York, in November 1775, members of the Philadelphia Sons of Liberty had urged Adams and other Massachusetts delegates to the Continental Congress to allow Virginians to take the lead.[37]

If a significant failure of factual accuracy is grounds for doubting an historian’s credibility, as McGlone implies, then by his history of the Frankford conference, McGlone is “Hoist with his own petard.” He erred on multiple counts. The date and location of the meeting in Frankford, Pennsylvania, is clearly identified in the diaries of John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, and in the Autobiography of Benjamin Rush.[38] Frankford was and is five miles north of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Adams’ Diary states that plainly. McGlone’s wild assertion that the meeting was held in Frankfort (near Utica) New York is difficult to excuse. Perhaps he consulted an atlas and, finding the existence of another Frankfort in New York, simply assumed that New York was the locus of the encounter. This is more than odd for several reasons. McGlone acknowledges that the meeting was with Philadelphians who came to advise the Massachusetts delegation about how to proceed at the Congress in Philadelphia. McGlone’s account has the Philadelphia men traveling to Utica in upstate New York to meet with Adams and company, who would have also been hundreds of miles off course from wherever they were intending to be.

The more puzzling misrepresentation is McGlone’s date of the Frankford event: November 1775. It is simply not even close. The Frankford conference took place near Philadelphia on August 29, 1774, just prior to the commencement of the First Continental Congress. McGlone has it taking place right in the middle of a session of the Second Continental Congress, months after George Washington had been appointed commander of the Continental Army in June 1775. The assertion that Adams and three others from Boston were in Frankfort, New York, in November of 1775 with nine other patriots is entirely spurious. Adams “remained at his post” in the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia from September 13 through December 9, 1775, serving on thirteen different committees.[39] It is simply ridiculous to suggest that in the middle of that session, Adams and at least a dozen others left Philadelphia and rode to the upstate region of Utica, New York and met with Sons of Liberty, also from Philadelphia. It just did not happen.

If McGlone’s error were historically inconsequential, typographical, or de minimus, it would be petty to mention it. But the Frankford Advice was at the heart of Adams’ explanation to Pickering—the explanation that McGlone’s article aims to contest. As a result, his error is significant, even egregious. Granted, McGlone’s thesis is multifaceted and his egregious historical error does not require that everything he wrote be discarded. But if McGlone deserves such a forbearing indulgence for factual errors, certainly Adams does as well.

Some historians have noted that Thomas Jefferson himself contested Adams’ letter to Pickering. Regarding the letter, Jefferson wrote to Madison, “in some of the particulars, Mr. Adams’ memory has led him into unquestionable error.” Jefferson went on to write that he would not “venture to oppose my memory to his, were it not supported by written notes, taken by myself at the moment and on the spot.”[40] Ironically, Julian Boyd, the editor of Jefferson’s papers at Princeton, demonstrated that Jefferson’s written notes were not in fact “taken by himself on the moment and on the spot.”[41]

More importantly, what Jefferson contested in Adams’s account is not the existence of the Frankford Advice. According to Adams, Jefferson was not only aware of the Frankford strategy, but also a willing party to it.[42] Jefferson did not contest that. What Jefferson questioned in his letter to Madison was whether or not there was a subcommittee to draft the Declaration. Adams biographer David McCullough believes that the two accounts may be harmonized and wisely opines, “possibly both were correct.”[43]

Given the fact that George Washington perceived the Frankford Advice in action, it seems highly unlikely that Jefferson would have been oblivious to it. McCullough has no doubt about the reality and significance of the Frankford Advice in the case of both Washington and Jefferson:

That there was political advantage in having the declaration written by a Virginian was clear, for the same reason there had been political advantage in having the Virginian Washington in command of the army . . . Had his [Adams’] contribution as a member of Congress been only that of casting the two Virginians in their respective, fateful roles, his service to the American cause would have been very great.[44]

The Frankford Advice as the Interpretive Lens for Understanding the Revolution

Adams offered the Frankford Advice as the cypher for accurately understanding the what really went on in Philadelphia as the United States was coming into existence. The meeting at Frankford had “given a colour complection and character to the whole policy of the United States, from that day to this [1774-1822].”[45] Adams was alluding to the fact that not only did the Frankford Advice result in the Virginians taking the lead during the Revolution, but as a consequence of their high profile reputations springing from the Revolution, also dominating the Early Republic as four of the first five Presidents of the United States were Virginians. In the end, John Adams claimed this is precisely what happened as a result of the Frankford Advice, with monumental implications:

Without it, Mr: Washington would never have commanded our armies, nor Mr: Jefferson have been the Author of the declaration of Independence, nor Mr: Richard Henry Lee the mover of it; nor Mr: Chase the mover of foreign connections . . . nor had Mr: Johnston ever have been the nominator of Washington for General.[46]

With the interpretive lens of the Frankford Advice, we might observe with greater understanding why Peyton Randolph of Virginia was unanimously elected chairman of the First Continental Congress just a few days after the meeting at Frankford. We might get greater clarity concerning why the Bostonian Samuel Adams, a stalwart opponent of the Church of England, advocated an Anglican clergyman to the Anglican president of Congress from Virginia to give the first prayer at the congress. We might even see a clearer motive for why Congress also appointed Horatio Gates and Charles Lee, neighbors from Virginia, as generals shortly after their selection of Washington.

Adams’ invoking the Frankford Advice as an essential lens for understanding the “big picture” of the Revolution may seem a bit simplistic and ignominiously self-serving. Nevertheless, his version is quite consistent with an abundance of the original evidence, and there is admittedly a compelling appeal in its explanatory power.

[1]James Thomas Flexner, Washington:The Indispensable Man (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1974).

[2]Jeff Dacus, “That a General be Appointed to Command,” Journal of the American Revolution (July 22, 2021), allthingsliberty.com/2021/07/that-a-general-be-appointed-to-command/.

[3]George Washington tothe Officers of Five Virginia Independent Companies, June 20, 1775, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 1, 16 June 1775 – 15 September 1775, ed. Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 16–19.

[4]Paul K. Longmore, The Invention of George Washington (University Press of Virginia, 1999), 167; also John R. Alden, George Washington: A Biography (LSU Press, 1984), 112, “Appointment of a Virginian was politically desirable, for it would satisfy all the Americans who wished to keep the Yankees in check.”

[5]Today the official spelling of the village near Philadelphia is “Frankford.” A 1752 map of the Philadelphia environs spelled it “Frankfort.” John Adams and his contemporaries spelled it, like the map, with a “t.” For the sake of uniformity, the proper spelling of the village is used in this article, except where a direct quotation dictates otherwise. John Adams to Timothy Pickering, August 6, 1822, in The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, 1850), 512-514 (JA to TP).

[8]William A. Dehler, “John Adams in the Continental Congress” (Loyola University of Chicago, 1939), 3.

[9]Adams Diary entry for August 29, 1774 lists Mifflin, McKean, Rutledge, Folsom and Sullivan and “a Number of Gentlemen from Philadelphia.” His 1822 letter to Pickering added Bayard and Rush.

[11]Harry Kyriakodis, “The ‘Frankfort Advice’: How a Small Philadelphia Suburb Helped John Adams Orchestrate the American Revolution.”Scribd, www.scribd.com/document/40191065/The-Frankfort-Advice-How-a-Small-Philadelphia-Suburb-Helped-John-Adams-Orchestrate-the-American-Revolution.

[12]John Adams, Diary entry for August, 29, 1774. The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 2, 1771–1781, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961),114–115.

[14]Jack McCarthy, “The Frankford Advice,” Hidden City, September 12, 2011.

[16]William Pitt Palmer, et al., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts: Preserved in the Capitol at Richmond (R.F. Walker, 1875), 57.

[18]Dale Carnegie, How to Win Friends and Influence People (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1936), 176; Nelson Mandela, Richard Stengel, Mandela’s Way: Fifteen Lessons on Life, Love, and Courage (New York: Crown Books, 2009), Chapter 4, “Leading from the Back,” 83; Douglas Van Praet, Unconscious Branding: How Neuroscience Can Empower (and Inspire) Marketing (New York: MacMillan, 2014), 141.

[19]Adams to William Tudor, September 29, 1774. The Adams Papers, 2:176–178.

[20]John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1943), 380.

[21]Adams to Tudor, September 29, 1774.

[22]Jeff Daucus, “That a General be Appointed to Command,” Journal of the American Revolution (July 22, 2021).

[23]Adams to James Lloyd, April 24, 1815.

[24]Dacus quotes Adams, “the greatest Number was for Ward.” Jeff Daucus, “That a General be Appointed to Command,” Journal of the American Revolution (July 22, 2021).

[25]Adams, Autobiography, 3-5.

[27]Adams to Lloyd, April 24, 1815.

[28]Charles Martyn, The Life of Artemas Ward (New York, 1921), 160.

[31]Adams to Lloyd, April 24, 1815.

[33]Eliphalet Dyer to Joseph Trumbull, June 17, 1775.

[34]In his Autobiography, written in 1805, Adams had previously enumerated the reasons he gave to Jefferson that Jefferson should be the draftsman: “That he was a Virginian, and I a Massachusettensian. That he was a southern man, and I a northern one.”

[35]Robert E. McGlone, “Deciphering Memory: John Adams and the Authorship of the Declaration of Independence,” Journal of American History, Volume 85, Issue 2 (September 1998), 411–438.

[38]Adams recorded, “We then rode to the red Lion and dined. After Dinner We stopped at Frankfort about five Miles out of Town. A Number of Carriages and Gentlemen came out of Phyladelphia to meet us.” John Adams, Diary, August 29, 1774. Paine noted, “Thence to Frankfort, there met by a No. of Friends from Philadelphia.” Robert Treat Paine, Diary, August 29, 1774, in Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789: August 1774-August 1775, Paul Hubert Smith, ed. (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976), 13. Rush wrote, “I went as far as Frankford to meet the delegates from Massachusetts, and rode into town in the same carriage with John Adams and two of his colleagues.” Benjamin Rush, A Memorial Containing Travels Through Life Or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush, Born Dec. 24, 1745 (old Style) Died April 19, 1813 (Lanoraie: Louis Alexander Biddle, 1905), 80.

[39]David Waldstreicher, A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams (John Wiley & Sons, 2013), 89.

[40]Jefferson to James Madison, August 30, 1823.Ford, ed., Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 10:267.

[41]Julian P. Boyd et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (27 vols., Princeton, 1950- ), 1:299-306.

[42]Adams allegedly reminded Jefferson of the Frankford Adviceas the first reason he should author the Declaration, “Reason first—You are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business.” JA to TP.

[43]David McCullough, John Adams (Simon & Schuster, 2001), 119.

5 Comments

Thanks to the author for reviving the “Frankford Advice” and its utility in triggering the Revolution by a united group of Colonies. I take exception, however, with the implication that, but for the Frankford Advice, MA would have dominated the Congress and gotten its way with regard to the leadership.

I think it highly unlikely that most of the other colonies would have deferred to MA. The New England colonies would have likely done so, but not so the others. First, the Southern colonies would have almost certainly been united – and in this case in favor of VA.

Secondly, three of the five largest colonies in population – even excluding slaves – were Southern: VA, MD, and NC, with PA and MA being the others in the top five. Thirdly, PA and NY would have likely acted independently of MA on many issues, and would have likely swayed NJ and DE.

In sum, there is no evidence of which I am aware that MA would have gotten its way with regard to a dominant leadership role, which includes personnel. The fact that MA was the most fiery and antagonistic colony toward Great Britain meant that it provided the spark of revolution; it does not follow, however, that MA would have been allowed to dominate the First Congress and other aspects of the Revolution.

Mr. Gardiner – I always enjoy reading another take on the “Frankfort Advice,” and you certainly busted many errors & fallacies.

Going through my notes of 2010 on this subject…

I believe that Adams & Pickering were touring the country & enjoying the attention, when “the letter” ended up as a publication in an 1822 newspaper.

Jefferson was blind-sided by the news of the Frankford Advice & subcommittees & began to question his own memory.

Three reasons Jefferson did not dispute the Frankfort Advice:

(1) Neither Jefferson or Rush attended the Convention of 1774 in Philadelphia and he would not comment on something on which he knew nothing.

(2) John Adams & Benjamin Rush both kept diaries or notebooks which made them sound infallible in their recollections.

(3) It was also very likely both Adams & Rush kept secrets from Jefferson. Neither Rush or Adams ever told Jefferson about this meeting. To learn this in 1822, after all their correspondence, this must have been hurtful and infuriating to Jefferson.

Meanwhile searching for the secret meeting place…

In 1774 twelve year old, Jacob Mordecai was sent to a large school kept by Captain Joseph Stiles … who “preserved in his school a very rigid discipline, such as in these days would be considered extremely severe, yet he seldom had occasion to use the rod or ferrule, though both made a conspicuous figure at his side.” Mordecai was appointed commissary of military stores, and states in one of his letters that:

“their uniform generally was a hunting shirt dyed as fancy pointed, and the youths of the schools and colleges in Philadelphia formed themselves in companies distinguished by different colors, armed with guns and trained to military exercises. In the month of September, 1774, these companies were all collected, and in the rear of the Rifle or Frock men marched to Frankford, about five miles from Philadelphia, for the purpose of escorting the delegates to town. They were on horseback, two and two, and with their military escort formed a long procession. The road was lined with people and resounded with huzzas, drums, etc., and exhibited a lively scene. In the humble office of sergeant I had thus the honor of escorting into Philadelphia the First American Congress.”

[Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, Volume 6 By American Jewish Historical Society Published By The Society, 1897 Pages 40-41 https://archive.org/details/publicationsofam05amer/page/40/mode/2up?q=Frankford&view=theater ].

J.M.

Well-written, fascinating article! Clarifies the American Revolution and early history!

Why even meet in Frankford?

“During the first Congress I spent a long evening at General Mifflin’s in company with General Washington, the two Adams’, General Lee, and several other gentlemen who acted a conspicuous part in the American Revolution. After supper several of the company looked forward to the probable consequence of the present measures, and state of things.

John Adams said he had no expectation of a redress of grievances, and a reconciliation with Great Britain, and as a proof of this belief, he gave as a toast, ‘Cash and gunpowder to the Yankies.’ ” — Benjamin Rush

A memorial containing travels through life or sundry incidents…

https://archive.org/details/memorialcontaini00rush/page/82/mode/2up

Thank you Joseph for the Dr. Rush link to the non-meeting at Frankford Pa. It clearly informs us that Dr.

Rush got into the carriage with the Adams and rode back into Philadelphia for the dinner conversation.

Using page 80, we can all agree that there indeed was NO MEETING in Frankford. No need be searching

for any taverns they may have used, nor any other landmarks needed to commemorate the occasion to

transmit some cryptic ADVISE on site. It, of course, still remains a mystery why 50 years later, Adams is

referring to this as: the Frankfort Advise?