“We have every reason to believe,” proclaimed the North Carolina Council of Safety, that “the emissaries of [the British] government are making use of every means in their power to induce the Indian Nations to fall upon the inhabitants of these [Southern] Colonies. Your own prudence will direct that you hold the Militia of your Department in readiness to repel any Hostilities which may be Commenced against us by any of the Indian Nations.”[1] North Carolina’s officials were gravely concerned. As the Revolution began in earnest in the eastern part of the state in 1776, the threat of surprise violence and sudden attacks from the Native American nations was growing. On the 11th of July, the Cherokee were heard to be readying for an attack by “boaling flour for a march and making other warlike preparations” with “about 600 warriors.”[2] War was coming to the Appalachians and western North Carolina.

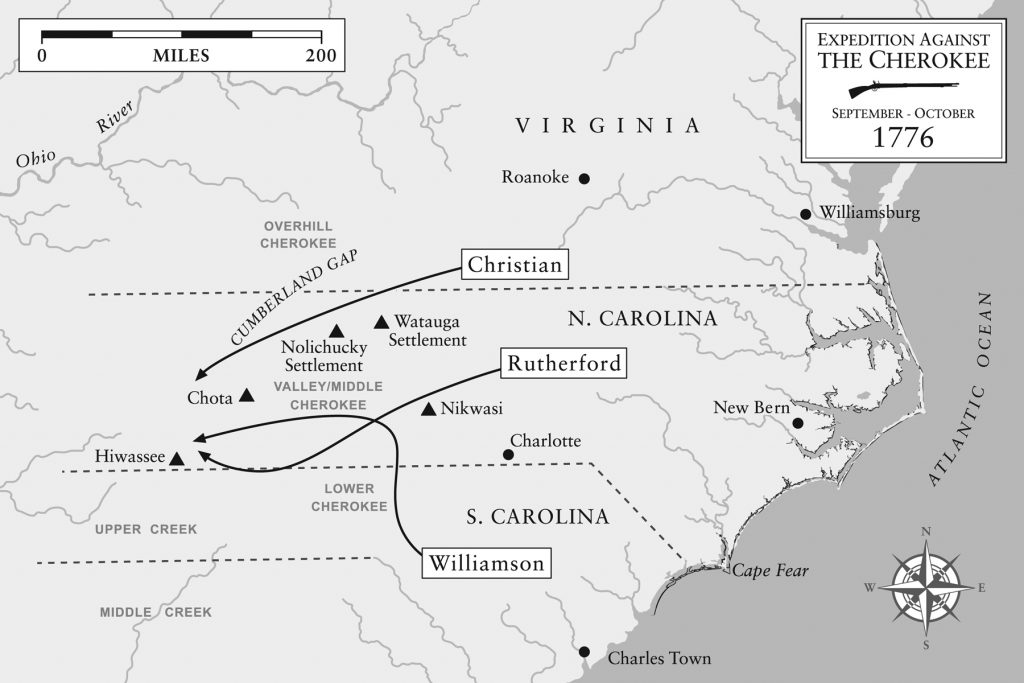

To handle the emerging threat, the colonies of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia decided that military action was needed. The Cherokee’s number was great and placed at about “2,000 or 2,500;—one half Overhills, the other below the Mountains . . . among the Creeks, from 4,000 to 5,000.”[3] While British Indian agents unsuccessfully tried to delay the Cherokee’s embarking on the war path until they could be coordinated with His Majesty’s regulars, Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford, an Irish-born French and Indian War veteran living in North Carolina, was tasked by the three colonies in June 1776 with taking the fight to the Cherokee.[4] Rutherford would lead only the portion of the expedition known to history as Rutherford’s Campaign. Leading the other portion was Col. William Christian of Virginia. His expedition has come to be known, appropriately, as Christian’s Campaign. Christian was a Virginian with military experience from conflicts throughout the 1760s and in Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774, and after returning to the Virginia tidewater area he read law with Patrick Henry.[5]

The most prominent commander under Colonel Christian was North Carolina Col. Joseph Williams. Williams was a trusted and able commander joining under Colonel Christian’s command and playing an important leadership role for the entire expedition.[6] With the splintering of Rutherford and Christian, subordinate commanders played more significant and prominent roles in their campaigns. Colonel Williams is the most notable subordinate commander to march with Christian’s campaign. Before becoming a North Carolina colonel, Joseph Williams “settled in Surry County [North Carolina] near [the] Shallow Ford of [the] Yadkin River, some years before the Revolutionary War. He was a delegate to the Hillsborough Convention of 1775,” and “he married Miss Lanier.”[7] William’s narrative comes from his recollection of the events of expedition, which were taken down just before his death in 1827. The time between the events and transcription of Williams account should cause the reader to take careful note of the details, timeline, and perspective provided. To begin, Williams recounted raising a battalion of Surry militia to fight the Cherokee in western North Carolina before marching in early September 1776 to Wythe County in southern Virginia.[8] He assembled with “Colonel William Christian, Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia Forces against the Cherokees.”[9] Together in the autumn of 1776 the commanders marched to war.

As a resident of the Yadkin river valley on the edge of the North Carolina frontier, Joseph Williams was all too familiar with the threat of Native raids. In the fall of 1776 the Cherokee towns which represented a threat to the southern colonies were located some distance from the Yadkin River Valley on the most western tip of North Carolina, west of modern-day Asheville, some even in modern day Tennessee and Georgia. Roughly three settlements were identified, although they were spaced out in various habitable spots. Colonel Williams recollected the Middle Settlement at some 878 members; the Lower Towns around 356, and the Over-hill Towns with around 757 people.[10] Williams and Christian were directed in early October toward the Over Hill towns on the Tennessee River with a force of nearly 3,000.[11]

The colonels’ goal was to attack the Over Hill towns between the, “10th and 15th of October.”[12] The mountainous terrain was challenging, but not impassible, as they pressed further into the interior country. While marching, a letter was dispatched from Colonel Christian to the other colonial commanders sharing that “the Indians have killed twenty of our people at different places by attacking small parties & helpless families. Our militia have killed twenty-five of their men, without the loss of one on our side.”[13] There had been no loss of life among the militia, a remarkable feat for troops in a conflict in the southern colonies.

In early October, before contacting the native towns, Colonel Williams remembered encountering a colonist who resided many years with the Indians and lived on the French Broad River, near modern day Asheville.[14] Displaying the Indian perspective, Williams recounted that the man argued for the Indians, who “wished no further invasion of their country.”[15] There was even talk of a treaty, but Christian, according to Williams, desired no negotiations.[16] While peace was set aside, looming skirmishes threatened to become a broader conflict, and colonial-Indian relations hung in the balance.

Halting at Fort Patrick Henry, called the Great Island by the militia, Williams ordered a portion of the men which would not be needed to remain behind.[17] Moving on and arriving at the outskirts of the Over Hill towns just after the 17th, Williams recounted, “although our forces were now in the vicinity, no Indians were to be seen.”[18] The Cherokee had removed the men, women, and children to safety, leaving behind structures, crops, and necessities. Both Williams and Christian chose to march further into the interior mountains. Finally, peace talks were reinitiated and accepted. Colonels Christian and Williams remembered the talks. Christian informed Virginia Gov. Patrick Henry, “on the 12th in the evening just before I was about to encamp, a white man with a Flag met me about five miles from the river. He said that the nation desired peace.”[19] Williams similarly recalled, “at length a treaty was formed with the chiefs of about half of the tribes.”[20] Remarkably, the colonists had not had lost a single man to violence.

It was only a fledgling peace. Unsigned by a number of the Appalachian tribes, the treaty was disdained from its inception. Some chiefs chose to abstain, muddying the terms of the agreement and protection for Appalachian colonists. A treacherous decision by the militia commanders, recounted by Colonel Williams, further degraded the peace. Williams wrote of their destruction of Towns and other property, which was accordingly done. They had great numbers of fat cattle and hogs, with poultry of every kind in abundance, which were used without restraint by the soldiers. Their corn, of which they had immense quantities, was burnt or otherwise destroyed. To those who were present it was a grievous spectacle to behold so many articles on which human life depended consigned to destruction.[21]

Cutting the Indians off from essential supplies would render them unable to make war for an extended period. It also asserted the colonists’ dominance. Yet, it presumably excluded the tribes that abstained from the talks, although no direct response is recorded. With scorched cornfields behind them, Colonel Williams, along with his commander, set to return in late autumn. Flimsy peace was secured, but they had sowed fury in the tribes as they departed and destroyed. Just before marching back Williams penned one of his few letters at the time of the conflict. He recounted a quick summary of events from the past several months for the President of the Provincial North Carolina Congress: “I marched three hundred men from Surry County, and joined the Virginians against the overhill Cherokee Indians, the whole commanded by Colo William Christian; we arrived in Tomotly (one of their towns) the 18th ult., & have been lying in their towns till this day.”[22] Dispatching the letter on November 6, Williams’ forces departed on the 9th, while Colonel Christian followed the next day with plans to rendezvous near Fort Patrick Henry.[23] The return journey for Colonel Williams required “less caution too,” so that the troops, “generally enjoyed good health and were in fine spirits.”[24] The Surry county militia made their way from the mountains into the foothills, and the Christian campaign dissipated, the militia satisfied that they had done their duty.

In his 1827 recollection, Col. Joseph Williams concluded by considering the results of such a bloodless expedition. He asserted, as a resident on the edge of Cherokee territory,

whatever might have been the disposition of the hostile party to commit aggressions subsequently to the destruction of their property, they were by that act rendered incapable, for a time, of giving efficacy to their designs. The business [of] producing substance for themselves was of paramount concern to all other objects.[25]

Col. Joseph Williams gave his command and men credit for stalling the Cherokee. The Second Cherokee War, as it became known, was not ended by peace. Instead, the Cherokee were incapable of continuing the war, and the colonists were too distracted and concerned with the British to further decimate the tribes. Williams’ explanation seems to suggest that had their crops not been destroyed the natives would have renewed the conflict. The inability to renew hostilities saved North Carolina from being heavily focused on the mountains, a necessary reprieve in light of the growing threat from the British on the coast for a colony that found it hard to raise sufficient militia to defend the eastern and western regions at the same time.

Williams also emphasized that the expedition was the salvation of the colonial Holstein river settlements deep in Cherokee country. “It is conceivable, and even probable, that the Christian campaign saved the infant settlements . . . from destruction.”[26] Even more, Williams recounted no remorse past or present for the destruction of native goods, crops, and homes of those with whom they had presumably made peace. Because the Cherokees’ will and sustenance was demolished, William’s campaign may have halted the Cherokee for an extended period of time, but, this is not certain; his sentiments immediately after the campaign were different from what he expressed in his 1827 recollections. As he returned to his Panther Creek Plantation on the Yadkin River in late autumn 1776, he was not confident. On November 22 he wrote to North Carolina chief executive Richard Casewell and promised to call on him in Halifax around the 8th of December. He also asked for “Commissioners to be appointed from each Colony” to the Indians and for North Carolina “to Station a Regiment at the mouth of Holston river.”[27] The expedition had established some-kind-of peace, but Colonel Williams recognized that the threat remained. He was correct to assert that native loyalty would remain contentious for British and colonial agents seeking to secure their strength and knowledge for the Revolutionary cause. For now, in the winter of 1776, the North Carolina military and political leaders had stalled the Cherokee and could turn their full attention to the British in the East.

[1]“Letter from the North Carolina Council of Safety to Griffith Rutherford, June 24, 1776,” Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South (CSRNC), 11:303-304, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr11-0165.

[2]“Deposition of Jarrett Williams Concerning the Actions of the Cherokee Nation, July 11, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:660-661, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0281.

[3]“Letter from Willie Jones to Richard Casewell, June 2, 1776,” CSRNC, 22:742-744, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr22-0554.

[4]Wayne Lynch, “Captain McCall & Alexander Cameron in the Cherokee War,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 28, 2016, allthingsliberty.com/2013/04/captain-mccall-and-alexander-cameron-in-the-cherokee-war/.

[5]Dictionary of Virginia Biography – William Christian Biography, www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvd/bio.php?b=Christian_William_d_1786.

[6]“Letter from Griffith Rutherford to Cornelius Harnett, August 6, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:726-727, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0316.

[7]Sam’l C. Williams, “Col. Joseph Williams’ Battalion in Christian’s Campaign,” Tennessee Historical Magazine 9, no. 2 (1925): 102.

[9]Ibid.; “Letter from William Christian to Patrick Henry, October 6, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:837-839, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0391.

[10]“Description by J. G. M. Ramsey of an attack by the North Carolina Militia on the Cherokee Nation [Extracts], 1853,” CSRNC, 10:881-885, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0391.

[11]“Letter from William Christian to Andrew Williamson, August 15, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:748-749, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0336.

[14]Williams, “Col. Joseph Williams’ Battalion,” 108.

[17]“Letter from William Christian to Patrick Henry, October 6, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:837-839, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0391.

[18]Williams, “Col. Joseph Williams’ Battalion,” 109.

[19]“Letter from William Christian to Patrick Henry, October 14-15, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:844-847, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0397.

[20]Williams, “Col. Joseph Williams’ Battalion,” 110.

[22]“Letter from Joseph Williams to the Provincial Congress of North Carolina, November 6, 1776,” CSRNC, 10:892, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0424.

[23]Williams, “Col. Joseph Williams’ Battalion,” 111.

[27]“Letter from Joseph Williams to Richard Casewell, November 22, 1776,” CSRNC, 12:912-913, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0441.

One thought on “North Carolina Colonel Joseph Williams in the Cherokee Campaign of 1776”

Well done! These are important events that don’t get enough attention.