On December 5, 2018, the State of Delaware announced that it had acquired the historic property at Cooch’s Bridge, site of the only Revolutionary War battle to take place in the First State. The acquisition included ten acres, several outbuildings, and the Cooch family’s ancestral home, a three-story structure built circa 1760.[1]

The house was first listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and has been documented as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey.[2] Cooch’s Bridge is much-beloved by local folks and after nearly 250 years, its legends, artifacts, and related primary documents remain an important part of Delaware history.

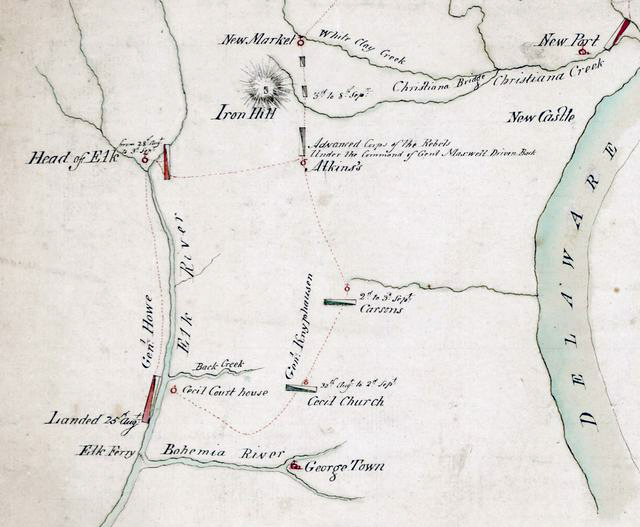

After a frustrating series of stalemates between British forces and American troops in New York City and New Jersey in the first half of 1777, British Gen. William Howe decided to try a new approach to capturing the rebel capital of Philadelphia. On July 23, 1777, General Howe and his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, left New York City with an armada of 265 ships carrying 18,000 troops. Continental Army scouts warily followed the progress of their fleet.

The Royal Navy’s Capt. Sir Andrew Snape-Hamond cruised the Delaware River in the British ship Roebuck, watching for suspicious activity on the part of the Americans.[3] Meeting with the Howe brothers in southern Delaware, Snape-Hamond suggested that because the Americans had barricaded the Delaware River with chevaux-de-frise, it would be more efficient for the British fleet not to sail directly upriver to Philadelphia but to sail instead southwest across the bottom of the Delmarva Peninsula and then up the Chesapeake Bay to march across Pennsylvania to Philadelphia.

Agreeing, the British sailed out of the Chesapeake Bay into the Elk River, with the Roebuck in the lead, followed by the troop transports. They headed for the landing at Elk Ferry on Turkey Point—a rugged, thinly-inhabited peninsula on the west side of the Elk River. Hessian Jägers, British light infantry, and British grenadiers, were personally led by the General Howe.[4] On August 25, after a rough ride through electrical storms, intense heat and days with no wind, Howe’s troops disembarked near Elkton, Maryland south of today’s Elk Neck State Park.

Anticipating these British movements, the Americans had marched southwest from Neshaminy, Pennsylvania through Philadelphia and over the border into Delaware. Coming straight down Philadelphia Pike (today’s Route 13) from Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, into Claymont, Delaware, Washington and his men continued past Brandywine Village to establish their headquarters on Quaker Hill.

The following morning, having learned that the enemy had begun to land “about six miles below Head of Elk opposite to Cecil Court House,” Washington, accompanied by Nathanael Greene, Lafayette, military aides and a strong troop of horse, moved southwest from Wilmington on a scouting expedition. From the summits of Iron Hill and Gray’s Hill on the Delaware-Maryland border they scanned the Maryland valley below. Although Gray’s Hill was within two miles of the enemy’s camp and they could see the tents, Washington and his men were unable to form a satisfactory estimate of the numbers of men who had landed.

A Hessian general looking up at them wrote:

We observed some officers on a wooded hill opposite us, all of them either in blue and white or blue and red, though one was dressed unobtrusively in a plain gray coat. These gentlemen observed us with their glasses as carefully as we observed them. Those of our officers who know Washington well, maintained that the man in the plain coat was Washington. The hills from which they were viewing us seemed to be alive with troops. My General [Howe] deployed 3,000 men and marched forward. As soon as they observed our advance, the Americans retreated; we caught only two dragoons. These dragoons and some Negro slaves confirmed that it was Washington with his suite and a strong escort looking us over. Most of our troops halted on and around this height.[5]

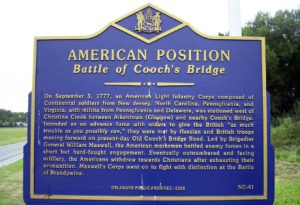

On August 28, Washington instructed the brigades that were with him (from Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and North Carolina), and militiamen from both Delaware and Pennsylvania to contribute reliable men to form a new light infantry battalion. As Journal of American Revolution contributor Gabriel Neville explains: “For the American army early in the war, “light infantry” usually meant “riflemen.” Though accurate at long range, rifles took longer than muskets to reload and could not carry bayonets. They were good for sniping at, harassing, and delaying the enemy.”[6]

This battalion was to consist of “one Field Officer, two Captains, six Subalterns, eight Serjeants and 100 Rank & File from each brigade.” These riflemen were not meant to fight a pitched battle against the advancing British army but to gather intelligence, harass the British, and act as an advance guard for American soldiers. They were to “be constantly near the enemy and give them every possible annoyance.”[7] The battalion was placed under the command of Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, a Presbyterian of Scottish descent born in County Tyrone, Ireland. His family settled in Warren County, New Jersey, where Maxwell would grow up to become active in Patriot political and resistance activity.[8]

Formed just one week before the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, Maxwell’s corps was composed of many individual officers and men who had had previous combat experience.

Although we are often told that the 1777 Battle of Cooch’s Bridge (also known as the Battle of Iron Hill), was an insignificant skirmish, well-known historical archaeologist Wade Catts states:

Judging by the pension applications, filed by aged veterans in their seventies and eighties, this conclusion is patently false. Like our WWII veterans, memories of the Revolutionary battles left deep and profound scars on survivors. Their own words, recorded in their pension files, speak to the magnitude of the fight on September 3rd, 1777. Adjectives such as “severe,” “bloody,” and “sharp” punctuate their recollections, clear indicators that, for those that fought here, Cooch’s Bridge was no mere skirmish. Even a British officer acknowledged the intensity of the fight, commenting that while many skirmishes were fought on the road to Philadelphia “none were considerable enough to deserve mention except the one at Iron Hill.”[9]

Reinforcing Catts’ point is a statement found in the pension records of William Walker, a soldier of the 4th Virginia Regiment:

we were met immediately after passing Chester, Pennsylvania with an express (stating that) that the enemy was landing at the Head of Elk . . . General William Maxwell being the commander we marched to a place called Iron Hill where we remained until the 2nd of September,the enemy being as yet stationary when a very bloody conflict ensued. As no historian has noticed this I refer you to Washington’s Official letters. For myself I can say that this detachment on that day deserved well of their country.[10]

On the 2nd of September Washington instructed Maxwell:

As several accounts seem to agree, that the Enemy mean to come out to morrow morning, I beg you will be prepared to give them as much trouble as you possibly can. You should keep small parties upon every Road that you may be sure of the one they take, and always be careful to keep rather upon their left Flank, because they cannot in that case cut you off from our Main Body . . . I gave the Map that I promised you to the Engineers to Copy, but they have not yet done it.[11]

Maxwell commandeered the Cooch house for his headquarters and placed his men in a series of small camps in the marshes, creek beds, and small ravines on either side of the road. Since the Americans could only guess which way Howe would try to approach Philadelphia, Maxwell divided his men between Iron Hill and Cooch’s Bridge. The Cooch property at the eastern base of Iron Hill is on Old Baltimore Pike, one of the original main roads leading from Philadelphia to Baltimore.[12]

The letters, journals and diaries of the participants help make the story of Cooch’s Bridge come alive. For example, George Washington wrote from his headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware to General Maxwell on September 3d 1777:

Sir,

Yours of three oClock this morning, I have received. I wish you very much to have the situation of the enemy critically reconnoitred—to know as exactly as possible how and where th[ey] lie—in what places they are approachable—where their several guards are stationed and the strength of them; and everything necessary to be known to enable us to judge, with precision, whether any advantage may be taken of their present divided state. No pains should be omitted to gain as much certainty, as can be had, in all these particulars. I am Sir Your most Obedt servant.[13]

A German participant, Ansbach-Bayreuth Jäger Lt. Heinrich Carl Philipp von Feilitsch, noted:

The 3rd—We marched out of our camp at four o’clock in the morning. At a distance of two and one-half miles we . . . shortly thereafter encountered an enemy corps of 3,000 men in the region of Wellstreg, or the Fort Euren Kill, or Katschers Mill (Gooch’s Mill). The enemy stood firm. The fire was extremely heavy and lasted about two hours. Only our corps was engaged and a few English. The enemy attacked three times. We lost one dead and ten wounded, while the rebels suffered nearly fifty dead and, according to the deserters, very many wounded. We made few prisoners. Our Jäger conducted themselves well and, after the enemy was driven back, we entered camp during the afternoon not far from that place. The affair began at eight o’clock and lasted until ten. The company had two wounded, a corporal and a Jäger.[14]

A British officer, Lt. Henry Stirke of the 10th Regiment of Foot’s light infantry company, wrote:

Septr 3d This morning about 5 O’Clock The Lt Infantry, Grenadiers, Hessian Chasseurs, Queens Rangers, some battalions of Brittish and Hessians, march’d under the Command of Sr Wm Howe, to take possession of the Iron Hills. About 8 O’Clock ye Hessian Chasseurs, and 2d Battalion of Light Infantry, attack’d a large party of the Rebels, strongly posted at a bridge, at the foot of the Iron hills, which after a faint resistance, was carried with very little loss. The Rebels had about 50 kill’d and Wounded. The 1st Battalion of Light Infantry endeavouring to turn the left flank of ye Rebels, and cu[t] off their Retreat, was prevented by an Impassable morass, which ye Guide was not acquainted with. At this pass there was 500 Regulars, and 300 militia, under the Commd of Genl Maxwell.[15]

General Howe’s main force, advancing east from Head of Elk, reached Aiken’s Tavern at present-day Glasgow, Delaware, about nine o’clock on the morning of September 3. On the road to Cooch’s Bridge, about a mile north of Aiken’s Tavern, Howe’s vanguard led by Lt. Col. Ludwig von Wurmb’s Jäger corps,[16] encountered Maxwell’s American light infantry corps.

The American ambush of the enemy spanned a length of road that followed a curving branch of the Christina River. They hid behind trees and rocks and laid round after round into the British. Initially the British had a hard time knowing where to return fire. After taking their shots, the Americans would fall back, reload, and fire again. In this way they fell back toward Cooch’s Bridge, using the familiar terrain to their advantage.[17]

More than 400 Hessians formed a line and, with the support of some artillery, advanced upon the Americans. Lieutenant Colonel Von Wurmb was described as being “continuously in front of the Jäger, encouraging them in every way, both by actions and by words.” In turn, von Wurmb reported that the Americans in the second line “defended themselves obstinately,” but were outflanked in hand-to-hand fighting. He sent one detachment to Maxwell’s left, hoping to flank his position, and supported the move with a bayonet charge against the American center.[18]

By this time, the sound and intensity of the firing was increasing so much that General Howe determined to send in two battalions of British light infantry—elite troops—in an attempt to outflank Maxwell’s line. Maj. John André noted of the 1st Battalion of Light Infantry, “The attempts made by our Troops to get round them were defeated by their being unable to pass a swamp.”[19]

It is probable that the “swamp”—which Lieutenant Stirke called an “impassable morass”—was in the present location of Sunset Lake, a mill pond created in the nineteenth century which had been marshland at the time of the battle. The 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry moved to the west and while it, too, encountered a swampy area, it was able to continue its advance.

It was not just the British and Hessians who were troubled by the marshy ground. According to local legend some nervous young Delaware militia men were sure they were surrounded by the British. The corn stalks and marsh grasses rustled in the dark. Louder, more horrendous noises made them run faster and faster across the soggy open space. In a panic their colonel told them to throw down their weapons. He yelled out, “We Surrender!” In the deafening silence that followed his admission of defeat, the militia men suddenly realized no one was there. They had surrendered to bull frogs.

Major André noted that the Americans, who numbered about five hundred, “disposed of themselves amongst some trees by the roadside, and gave a heavy fire as our Troops advanced, but upon being pressed ran away and were pursued above two miles. At first retreating they fired from any advantageous spot they passed, but their flight afterwards became so precipitate that great numbers threw down their arms and blankets.”[20]

The advance guard of Hessians led by Capt. Johann Ewald soon headed up the road from Aiken’s tavern, about five miles east of Head of Elk and three miles south of Cooch’s Bridge. Struck by a volley of fire from the well-concealed American camps, six Hessians were killed or wounded. Ewald wrote, “My horse, which normally was well used to fire, reared so high several times that I expected it would throw me. I cried out, ‘Foot Jäger forward!’ and advanced with them to the area from which the fire was coming . . . At this moment I ran into another enemy party with which I became heavily engaged.”[21]

Lieutenant Colonel von Wurmb ordered that the advance guard be supported. Ewald later reported,

The charge was sounded, and the enemy was attacked so severely and with such spirit by the Jäger that we became masters of the mountain after a seven hour engagement . . . The majority of the Jäger came to close quarters with the enemy, and the hunting sword was used as much as the rifle . . . The Jäger alone enjoyed the honor of driving the enemy out of this advantageous position.[22]

The final phase of the battle was fought near the Cooch’s house. This third American line held for a time, but the Hessians, now reinforced by the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry, forced the Continentals back from the bridge. The Jägers’ had with them one- and three-pound cannons loaded with grape shot which was used to deadly effect. British artillery officer Francis Downman saw “a corporal and five men lying near together, killed by grape shot.” The British light infantry now stormed across the bridge.[23]

Maxwell’s Americans, their ammunition expended and facing a large enemy force, withdrew, moving east into the thick woods, then toward the village of Christiana. The British now controlled the field, holding the bridge and the main road to Philadelphia.

George Washington to John Hancock

Wilmington [Delaware] Septr 3d 1777. 8 oClock P.M

Sir

This Morning the Enemy came out with considerable force and three peices of Artillery, against our Light advanced Corps, and after some pretty smart skirmishing obliged them to retreat, being far inferior in number and without Cannon. The loss on either side is not yet ascertained. Ours, tho not exactly known, is not very considerable; Theirs, we have reason to beleive, was much greater, as some of our parties, composed of expert Marksmen, had Opportunities of giving them several—close—well directed fires; more particularly in One instance, when a body of Riflemen formed a kind of Ambuscade.

They advanced about Two miles this side of Iron Hill, and then withdrew to that place, leaving a picket at Coach’s Mill, about a mile in Front. Our parties now lie at White Clay Creek, except the advanced pickets which are at Christiana Bridge.

On Monday a large Detachment of the Enemy landed at Cecil Court House, and this morning I had advice of their having advanced on the New Castle Road as far as Carson’s Tavern. Parties of Horse were sent out to reconnoitre them, which went Three Miles beyond the Red Lion, but could neither see nor hear of them, Whence I conjecture, they filed off by a road to their left and fell in with their Main body.

The design of their movement this morning seems to have been to disperse our Light Troops, who had been troublesome to ’em, and to gain possession of Iron Hill to establish a post most probably for covering their retreat in case of Accidents. I have the Honor to be with great respect Sir Yr Most Obedt servt. [24]

An anonymous British diaristsummed up the story:

Sepr—– the 3 Our Army Consisting of the Light Infentry gradiers Conoal [Colonel] Morises Raingers and Heaseans Cheeuars Marched at Day Break and fell in With the Rebels At A Very strong pass at Iron hill and they Soon Retreated of[f] to the Woods Leaving ther dead and Wounded on the ground. They had Sixty kild Which was in the Woods Some days befoare they Were found by Information of Some Disarters.

2d [i.e. two] Light Companys of the 2d. Battalion Advanced three Miles of[f] from the picquett and Returnd the same Night With Oppesion.[25]

General Howe’s official report of October 10, 1777, stated that on September 3:

the Hessian and Anspach chasseurs and the 2nd battalion of light infantry . . . fell in with a chosen corps of one thousand men from the enemy’s army, advantageously posted in the woods, which they defeated with the loss only of two officers wounded, three men killed and nineteen wounded, when that of the enemy was not less than fifty killed and many more wounded.[26]

As the American soldiers retreated from the battle, the fallen were left behind to be buried by the British. People claim twenty-four graves were dug for the fallen colonials, but it is surmised that the loss of life was more likely to have been about forty to fifty deaths on each side. There is no indication there was only one body per grave or that anyone made much effort to retrieve all the bodies from the battlefield. The casualties at Cooch’s Bridge remain beneath this battlefield someplace between today’s village of Glasgow (known then as Aiken’s Tavern) and the vicinity of Cooch’s Bridge. It’s not clear where these bodies were buried, but after some work by a team of archaeologists from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, a few possible sites have been identified and will be further investigated.[27]

Two days after the battle, George Washington wrote to Congress:

We have not been able to ascertain the Enemy’s loss in the late Action by any other way, than by a Woman that came from their Camp yesterday, she says she saw Nine Waggon loads of Wounded. I think this probable because we had about forty killed and wounded, and as our Men were thinly posted they must have done more damage upon a close Body, than they received.[28]

The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge has long been considered to have been a skirmish. Local people love the legend that the Betsy Ross flag first flew at Cooch’s Bridge and enjoy ghost stories related to the battle. Archaeological evidence and recently discovered documents indicate the action was livelier and more historically significant than previously realized.

Although we don’t know how many people died in the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, two very similar ghost stories circulate. Both tell us that a soldier whose head was shot off in the battle appears on foggy, moonless nights as a headless apparition.

Virginia Paranormal tells us:

The legend of the Ghost of Cooch’s Bridge is documented earlier than most local legends with an article in the Newark Post in 1910. At that time, no one living knew when the legend was born. In short, a British scout was dressed as a specter on a light colored horse and was investigating and testing the defensive lines of the Colonials. The scout wore steel plating over his chest and back. Shots had been fired and hit their target, but the specter rode on, unchallenged. After a few encounters with the specter, a corporal aimed higher and struck the scout in the head, felling him and the ruse was discovered . . . later, in a spectacular example of irony, the scout who had posed as a specter became the specter he had so well impersonated and so the Ghost of Cooch’s Bridge came about and on moonlit foggy nights, he can be seen approaching the bridge, testing your nerves where the Colonial lines of defense once braced.[29]

The other story is centered around Welsh Tract Church a few miles south of Iron Hill. Whether this ghost’s name was made up by the story teller, Ed Okonowicz, or is the name of an actual soldier is unknown.

During the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge in 1777, when a British cannonball struck the brick facade of Welsh Tract Church near Newark, a young volunteer fighter named Charlie Miller lost his head as he was riding through the cemetery next to the church. An historic church graveyard—located along Welsh Tract Road, off Route 896 south of Delaware Stadium—is associated with Delaware’s Headless Horseman. A British cannonball decapitated Charlie Miller, a young Colonial volunteer during the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge.

His restless spirit is said to still roam the woods near I-95[30]

The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge was the opening engagement of the Philadelphia Campaign, and the result of the battle was a British victory. This was not a turning point in the campaign, but it was more than a skirmish. The battle served to affirm to the British that their invasion and intent to capture Philadelphia would be contested by George Washington and his army.

After the battle, British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis took up residence at the Cooch home and used it as his headquarters for five days. Local lore tells us Cornwallis stabled his horses inside one of the homes’ living rooms.

On September 6, British Gen. James Grant arrived with two battalions that had been left at Head of Elk to facilitate the unloading and departure of the fleet. On September 8, the British and Hessians burned the Cooch mill then marched north to Chadds Ford.

Maj.Carl Leopold Baurmeister, adjutant general of the Hessian forces in North America, reported:

The spirited manner in which Lieutenant Colonel von Wurmb & the officers and men yesterday engaged & defeated the chosen advance corps of the enemy deserves the highest encomiums & calls for the General’s fullest acknowledgements . . . Tomorrow morning, by five o’clock, camp must be broken, and the regiments must be at the front ready to march. The old pickets will have been previously withdrawn. The new pickets of the English regiments will make up the vanguard and take along two of Lieutenant Willson’s 3-pounders; then will follow the English dragoons, except for that one non-commisioned officer and six dragoons who will march at the head of the pickets; then all the quartermasters and officer’s men from the battalions of the 71st Regiment; then the 3rd, (15th, 17th, 42nd, 44th Regiments) and 4th (33rd, 37th, 46th, 64th Regiments) English Infantry Brigades by half companies; then the Hessian Leib Regiment, Mirbach’s Regiment, the combined battalion (the Fusilier Battalion Loos, the remnants of Rall’s Brigade) and half of von Donop’s Regiment, then the baggage (the wagons of the generals first and the rest in the same order as the regiments).

The baggage will be followed by the cattle, and the guards assigned to it will keep the drovers in order. The Hessian pickets will patrol along both sides of the baggage and cattle train, keeping particularly close watch on the right, Lieutenant Colonel Heymell (Carl Philipp Heymell) will form the rear with the other half of von Donop’s Regiment, which is to be preceded by Lieutenant Willson’s two remaining 3-pounders. Everyone is warned against setting fire to houses, barns, or other buildings along the line of march. At each building a double post will be left, which is to be relieved by each successive battalion until the rear guard. In addition, one officer and fifteen dragoons will follow the rear guard.[31]

On September 11, 1777, the two armies would meet again at the Battle of Brandywine.

[1]Obituary, Edward Cooch, Newark Post. September 23, 2010. “Ned” Cooch was the seventh generation of his family to occupy the family home built in 1760 by his ancestor, Col. Thomas Cooch. www.newarkpostonline.com/news/local/law-firm-founder-civic-leader-ned-cooch-dies-at-age-90/article_04fff5a1-2ca6-56a0-980d-256a1924329c.html.

[2]Doug Denison, Focus, history.delaware.gov/2018/12/12/state-of-delaware-to-acquire-historic-property-at-coochs-bridge-the-site-of-the-states-only-revolutionary-war-battle/.

[3]Richard Hiscocks, “The Philadelphia Campaign – August to November 1777,” morethannelson.com/the-philadelphia-campaign-august-to-november-1777/.

[4]Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign Volume One Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia (Mechanicsville, PA: Stackpole Books. 2006), 133.

[5]Friedrich von Muenchhausen, At General Howe’s Side, 1776-1778, The Diary of General William Howe’s Aide de Camp. (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 26.

[6]Gabriel Neville, “The ‘B Team’ of 1777: Maxwell’s Light Infantry,” Journal of American Revolution, April 10, 2018, Allthingsliberty.com/2018/04/the-b-team-of-1777.

[7]John Marshall, The Life of George Washington, 5 vols. (Philadelphia, G.P. Wayne, 1804-1807), 3:141.

[8] When the Revolutionary war broke out Maxwell was commissioned as colonel of the 2nd New Jersey Regiment. The regiment was sent to Quebec under Gen. John Sullivan in early 1776 and was involved in the Battle of Trois-Rivières before the Continental Army retreated to Fort Ticonderoga. Promoted to brigadier general, Maxwell returned to New Jersey to join Washington’s army after its retreat across New Jersey following the loss of New York. revolutionarynj.org/rev-neighbors/william-maxwell-2/.

[9]Wade P. Catts, “Remarks for the Dedication of the American Memorial at Cooch’s Bridge Battlefield,” http://pencaderheritage.org/main/battmem/batt_wc.pdf.

[10]Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters. Pension application of William Walker S6340 f30VA, revwarapps.org/s6340.pdf.

[11]George Washington to William Maxwell, September 2, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0127.

[12]Cooch’s Bridge is two miles southeast of Newark and one mile east of Del. 896, in New Castle County, Delaware.

[13]Washington to Maxwell, September 3, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0272.

[14]Todd Post, “Battle of Cooch’s Bridge,”secondvirginia.wordpress.com/2010/09/03/coochsbridge/.

[15]Henry Stirke, ‘A British Officer’s Revolutionary War Journal, 1776–1778,’ Maryland Historical Magazine56 No. 2 (June 1961), 168.

[16]Jörn Meiners, “The Unknown Marburger – Another Portrait Of Jager Colonel Von Wurmb Is Found,” jsha.org/articles/001-11_JSHA2008.pdf.

[17]“On the March to Brandywine: Battle of Cooch’s Bridge,” www.ushistory.org/march/phila/tobrandywine_4.htm.

[18]Wade Catts, “The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge,” coochsbridge.wildapricot.org/Battlefield-History.

[19]John André, Major André’s Journal: Operations of the British Army under Lieutenant Generals Sir William Howe and Sir Henry Clinton, June 1777 to November 1778(New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1968), 42–43.

[21]Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, trans. & ed. Joseph Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 77.

[23]Catts, “The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge.”

[24]Washington to John Hancock. September 3, 1777, www.founders.archives.gov/?q=Cooch%27s%20Bridge&s=1111311111&sa=&r=3&sr=.

[25]Post, “Battle of Cooch’s Bridge.”

[26]K. G. Davies, ed. Documents of the American Revolution, 1770–1783(Shannon and Dublin, 1972–81), 14:202–9.

[27]Mark Eichmann,“Site of Delaware’s only Revolutionary War battle to be preserved,” whyy.org/articles/site-of-delawares-only-revolutionary-war-battle-to-be-preserved/.

[28]Washington to the president of Congress, September 5, 1777, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, vol. 9, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933), 187.

[29] Virginia Paranormal. The Ghost of Cooch’s Bridge at the Pencader Heritage Museum

paranormal-videos.com/the-ghost-of-coochs-bridge.

[30]Ed Okonowicz, “Haunted History: Delaware’s Headless Horseman,” www.udel.edu/udaily/2018/october/haunted-history-275-celebrating/; Brandon Holveck, “A Headless Horseman from the Revolutionary War Haunts a Church on Welsh Tract Road in Newark,” www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2019/10/30/delaware-haunts-8-places-in-and-around-delaware-with-notable-ghost-tales/2494242001/.

[31]Carl Leopold Baurmeister, Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals,trans. Bernhard A. Uhlendorf (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957).

3 Comments

Great article by Kim Burdick. Highly recommend her book “Revolutionary Delaware”.

Chris Mlynarczyk

President – 1st Delaware Regiment

Thanks, Chris! Wishing you and all 1st Delawre a very Happy New Year!

Thanks, Chris! Happy New Year!