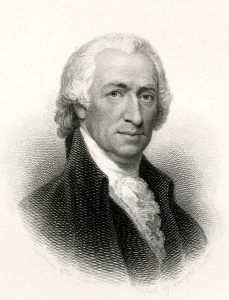

The debate over mandatory vaccination for Covid-19 has led to many articles referring to how George Washington handled a similar issue, this one involving smallpox, with the Continental Army early in the American Revolution. With the advantage of hindsight, the decision Washington made to fully inoculate (not vaccinate) his army may today seem obvious, but it wasn’t so simple for Washington and the others who lived it in real time. It’s worth revisiting exactly how this decision came to pass.

“The small Pox! The small Pox! What shall We do with it?” wrote an exasperated John Adams.[1] Good question. The story of how Washington answered it provides insight into his vaunted leadership and ability to learn and change, as well as the trust his soldiers had in him. How smallpox was handled is an underrated factor in how the army lived to fight and eventually win the war.

Caused by the variola virus and extremely contagious, smallpox was the most deforming and lethal of the plague-like epidemics of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Symptoms included severe pitting of the skin, eyebrows and lashes falling out, scarring so severe as to sometimes close up the nostrils, and even blindness.[2] Persons infected with smallpox are contagious for a period of about seventeen to twenty days and afflicted for twenty-one to twenty-four days after an initial asymptomatic period. There is a period of time (generally one day) in which individuals are contagious but are either asymptomatic or have only begun to experience minor symptoms such as fever, headaches, body aches, nausea, and malaise, which could be attributed to other ailments.[3] The smallpox virus is capable of surviving for a considerable time (days or even weeks) outside of the human body, making it much more easily transmitted and enabling its weaponization.

Washington himself, at age nineteen, had contracted smallpox in 1751 on a trip to Barbados with his half-brother Lawrence. No records were kept as to the struggle that ensued, but a twenty-four-day gap in Washington’s diary attests to the severity of the disease. Thankfully for a nation yet to be born this was another of many close brushes with death he survived, leaving him with only some of the characteristic skin pockmarking from the disease (and possibly, some theorize, rendering the future “father of his country” sterile).

Given the limited technology of the day, Washington did not have many options from which to choose in protecting his troops from contagion. There were two approaches: quarantine and inoculation. Initially, he opted for the former and opposed inoculation. His eventual conversion to inoculation illustrated his ability to learn and change based on new information and necessity, but this conversion didn’t come easily.

The close quarters in which an army unit works and their movement around the country made them excellent vectors for spreading such a highly communicable disease both to one another and to the general population. As Jonathan Trumbull, Sr. was to later observe, “our returning Soldiers have spread the Infection into almost every Town in the State, a Mischief that cannot happen when the Distemper is out of the Army.”[4] The best available treatment, in Washington’s early view, seemed to be to quarantine infected people so they would not expose others. For an army on the move, this was difficult and ineffective. Inoculation, although it also required quarantines, would seem to be a much more effective option, at least in retrospect.

It is important to understand exactly how inoculation (sometimes called “variolation”) worked, as it is different than the modern and familiar solution, vaccination, and the two are sometimes confused.

To inoculate a person, you had to make an incision (usually in the arm or leg) and insert a thread containing live smallpox taken from a current sufferer. The result was that the inoculated person got a (usually) milder version of the disease and, if they survived, would have immunity against future exposure. This differs from vaccination, where in its initial forms a milder version of the virus was injected into the patient.

The basis for the first widespread and successful method of vaccination came in 1796 from British physician Edward Jenner, based on his observation that people milking cows on the farm seemed to have an immunity to smallpox. Jenner made the connection that this immunity resulted from their exposure to the cow pox. By injecting people with this less virulent version of the smallpox virus he was able to give them immunity. Viruses were unknown, but doctors were able use what they observed worked. But this tool was not at Washington’s disposal in 1775, leaving him to consider inoculation as the only alternative to quarantine.

Inoculation had some distinct disadvantages: First, inoculated people could easily spread the virus if not strictly quarantined, risking starting an epidemic of your own making. The potential for spread is why many leaders of the day opposed inoculation. The requirement for a tight quarantine made inoculation on a large scale difficult. In addition, doing this on a mass scale put a large portion of military forces under quarantine, making ill and healthy forces alike vulnerable to enemy attack. Washington was already working with an inexperienced and shorthanded force, so purposely disabling a large portion of troops, despite a longer-term gain (immunity), would be highly risky and would have to be done in the strictest of secrecy.

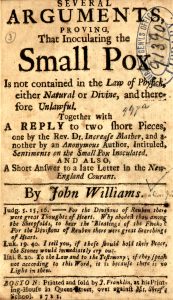

Last, there was a still a dash of superstition and doubt about the efficacy inoculation and the risks it entailed. Rev. Cotton Mather, a famous inoculation advocate during the severe Boston smallpox epidemic of 1721, was taken to task for committing “acts against god” for promoting inoculation. Feelings ran so strongly that someone attempted to bomb Mather’s home.[5] John Adams was an early convert among the founders, successfully inoculated in 1764. While the process was not without its risks, the death rate from inoculations was roughly 2 percent. Smallpox contracted “in the wild” could have a death rate that reached over 40 percent depending on time and place.[6]

The perception of danger resulted in inoculation being made illegal in a number of colonies, a list that at one time or another included New York, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Virginia, Maryland, and Massachusetts, the latter where Washington was operating in 1775. Capturing much of the thinking behind these bans, Trumbull observed in a letter to Philip Schuyler, subsequently relayed by Schuyler to Washington, that “innoculation for the small pox I find has been practised by Troops on the March to join your Army—I hope a practice so pernicious in every Respect will be discouraged . . . Indeed Sir if it is not timely restrained it appears to me it must prove fatal to all our operations and may ruin the Country”[7] If Washington had any thought of mass-inoculation of his forces, he had some minds besides his own to change.

The Boston that Washington held under siege in 1775 through early 1776 had a number of smallpox outbreaks. It is likely that the presence of smallpox in the city was to some degree responsible for Washington’s reliance upon siege rather than attacking the British during the fall and winter.[8] During the siege, Washington’s army had its share of outbreaks as well, which he tried to control with quarantines of infected soldiers. At this point, in conjunction with local authorities, inoculation was, at least officially, off the table, although there may have been scattered “rogue inoculations” among his troops.

Obedient to the prevailing laws, Washington was still advocating the quarantine approach, setting up a smallpox hospital for that purpose near Fresh Pond, about a mile and a half west of the Cambridge common. A sentry was deployed to ensure that anyone coming or going had proper clearance from the medical staff. Any man suspected of having the disease was to be removed at once to this quarantine location. To further mitigate against the spread of the disease, Washington issued a July 4, 1775 General Order that included a provision that “No Person is to be allowed to go to Fresh-water pond a fishing or on any other occasion as there may be danger of introducing the small pox into the army.”[9]

The British, in Washington’s opinion, may have been using smallpox to prolong the siege. “the small pox rages all over the Town, Such of the Military as had it not before are now under innoculation—this I apprehend is a weapon of Defence they Are useing against us”[10] The danger that smallpox held for the army not only influenced Washington’s decision to lay siege upon Boston for many months, but also explained his extreme caution when he moved to occupy Boston after the siege.[11] After the British abandoned Boston on March 17, 1776, Washington singled out one thousand troops who already had immunity to be the first to re-occupy the city. Smallpox continued to swirl around Boston as people sought to return to their homes or reunite with friends and family.

Boston would take until mid-September 1776 to get the upper hand on this round of the epidemic.[12] Meanwhile, Washington’s force moved on to New York. Smallpox was still a factor, and Washington was still in quarantine mode. On May 26, 1776, he issued a general order directing that “Any Officer in the Continental Army, who shall suffer himself to be inoculated, will be cashiered and turned out of the army, and have his name published in the News papers throughout the Continent, as an Enemy and Traitor to his country.”[13]

A few soldiers were surreptitiously inoculated, but despite the tough talk “none of the officers found to have gotten inoculated appear to have been punished. Nor are there more penalties noted in the general orders. No names were ‘published in the News papers throughout the Continent.’”[14] As in Boston, Washington established a smallpox isolation hospital, this time on an island in the East River, and ordered a halt to all inoculations. The general warned that “any disobedience to this order will be most severely punished.” The Continental Congress supported Washington, and when a private physician in the State of New York was caught inoculating soldiers, he was jailed.[15]

While this was Washington’s official posture, his thinking was starting to shift toward the possibility of pursuing a policy of mass inoculation. First, smallpox gave the British Army a strategic edge, in that many of the troops had been exposed at an early age growing up on the European continent,[16] and the British routinely practiced inoculation. It is unclear whether the British army required inoculation, but for many soldiers it was already unnecessary. At peak, it has been estimated that 30-35 percent of Washington’s force was unable to fight due to illness, much of it smallpox,[17] a disadvantage he could ill afford.

Second, inoculation would reduce his exposure to what we now call “biological warfare,” a tactic allegedly used by the British against American Indians in the Seven Years’ War.[18] During the siege of Boston, British Gen. William Howe released people from the city, ostensibly due to food shortages, and the subsequent introduction of smallpox to the colonial forces sustained the standoff, effectively preventing a military confrontation Howe was not confident of winning.[19] Washington suspected that these refugees were infected with smallpox and intended by Howe to infect his army. “General Howe has ordered 300 inhabitants of Boston to Point Shirley in destitute condition,” wrote Washington to Congress. “I . . . am under dreadful apprehensions of their communicating the Smallpox as it is rife in Boston.” Later, “four British deserters arrived with frightening news. Howe, they claimed, had deliberately infected fugitives with a design to spread the Small-Pox among the Troops.”[20] Washington was disinclined to believe Howe was capable of such an atrocity—“I could not Suppose them Capable of [deliberately passing on the infection]—I now must give Some Credit to it”[21]—but at the same time he redoubled his quarantine efforts and was careful to isolate refugees from his troops where he could.

Third, inoculation improved recruiting and decreased desertion rates for the chronically undermanned Colonial forces. The prospect of being exposed to smallpox in its “wild” form was much more daunting than that of undergoing a much less risky inoculation. If recruits could be inoculated upon entry into the army, they would be safe from the pox and more likely to stay.

Fourth, and probably most compelling, was experience, not only from Boston but from the disastrous outcome in the Battle of Quebec. The disaster at Quebec had occurred in late December 1775, and the more details that came out the worse it sounded, and smallpox was the culprit. “The Situation of our Affairs in Canada is truly alarming” Washington wrote to Phillip Schuyler.[22] Just prior to the retreat, Gen. John Thomas, a doctor himself who eventually succumbed to the disease, reported that only 1,000 of the force of 1,900 were combat ready, primarily due to smallpox. Engaging in a little germ warfare of his own, Sir Guy Carlton, in charge of British forces in Canada “apparently sent smallpox victims into the American lines,”[23] adding momentum to the already burgeoning outbreak. Despite the dismal failure in Canada, Washington was reluctant to consider inoculation of the troops because of the way undisciplined and haphazard efforts at inoculation (sometimes self-inoculation) had spread the disease among the troops.[24]

In January 1777, Dr. William Shippen, Washington’s director general of hospitals, was authorized to perform some inoculations. Shippen reported that “I found a great number of your troops here in a miserable situation, which I have the pleasure to inform you are now in a comfortable situation.”[25] Still, Washington would not cross the threshold to a full inoculation order. He wrote to Shippen on January 28, 1777 again demurring on issuing a full order: “In your last you mentioned your Intention of innoculating all the Recruits who had not had the small Pox, this would be a very Salutary Measure if we could prevent them from bringing the Infection on to the Army, but as they cannot have a change of Cloathes, I fear it is impossible.”[26] On the same date, he asked Horatio Gates, whose troops were due to undergo a similar regimen, to halt the process. “I am very much afraid that all the Troops on their march from the Southward will be infected with the small pox, and that instead of having an Army here, we shall have an Hospital . . . Doctor Shippen wrote to me that he intended to innoculate the Troops as they came in, but that never can safely be done, except innoculation was to go thro’ the whole Army.”[27]

Reconsidering, Washington decided to take the plunge. In a February 5, 1777, letter to John Hancock, the President of Congress, he wrote:

The small pox has made such Head in every Quarter that I find it impossible to keep it from spreading thro’ the whole Army in the natural way. I have therefore determined, not only to innoculate all the Troops now here, that have not had it, but shall order Docr Shippen to innoculate the Recuits as fast as they come in to Philadelphia.

A letter to Shippen went out the next day. The original draft of Washington’s letter to Hancock testifies to his ongoing ambivalence. That draft read:

The small Pox is making such Head in every quarter that I am fearful it will infect all the Troops that have not had it. I am divided in my opinion as to the expediency of innoculation, the Surgeons are for it, but if I could by any means put a Stop to it, I would rather do it. However I hope I shall stand acquitted if I submit the Matter to the Judgment and determination of the medical Gentlemen.[28]

So what finally changed the General’s mind? It appears to have been an accumulation of information rather than one specific event. The dominos fell quickly from here. On February 6, he wrote Dr. Shippen, “Finding the Small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running through the whole of our Army, I have determined that the troops shall be inoculated . . . I trust in its consequences will have the most happy effects.”[29] Congress, in receipt of the February 5 letter to Hancock, ordered “That the Medical Committee write to General Washington, and consult him on the propriety and expediency of causing such of the troops in his army, as have not had the small pox, to be inoculated, and recommend that measure to him.”[30] The Medical Committee followed a day later with a response to Washington that Congress “directed [us] to request your Excellency to give Orders that all who have not had that Disease may be Inoculated, if your Excellency Shall be of Opinion that it can be done without prejudice to your Operations.”[31]

With this decision to proceed, one of the concerns about using inoculation now surfaced—the process took about four weeks. This made secrecy imperative. If the British caught wind of the fact that this much of the already low fighting force was out of commission, a timely attack could make quick work of the rest. Much of the critical work was done in the winter quarters in Morristown in early 1777, but some was even done during the difficult next winter in Valley Forge. Secrecy held in both instances. Washington, writing to Trumbull in a letter which must have been somewhat satisfying due to the former’s earlier opposition to inoculation, Washington wrote in January 1778, “Notwithstanding the Orders I had given last year to have all the Recruits innoculated, I found upon examination, that between three and four thousand Men had not had the Small Pox. That disorder began to make its appearance in Camp, and to avoid its spreading in the natural way, the whole were immediately innoculated.”[32]

The Continental Army had executed the first large-scale, state-sponsored immunization campaign in American history.[33] As British medical writer Hugh Thursfield later wrote “I think it is fair to claim that an intelligent and properly controlled application of the only method then known of defeating the ravages of smallpox, which in the years 1775-76 threatened to ruin the American cause, was a factor of considerable importance in the eventual outcome of the War of Independence.”[34] More broadly, the example set by Washington’s inoculation program was a positive contribution to public health, legitimizing inoculation until Jenner’s vaccine made its appearance.

[1]John Adams to Abigail Adams, June 26, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-02-02-0013.

[2]Ann M. Becker, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease during the American Revolutionary War,” The Journal of Military History Vol. 68, No. 2 (April 2004), 384.

[3]Elizabeth Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-1782 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), chart on page 19.

[4]Jonathan Trumbull, Sr. to George Washington, February 24, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0466.

[5]Becker, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army,” 387.

[7]Peter Force, American Archives – A Documentary History, Series Five (Washington: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1833), 1116.

[8]Mary C. Gillet, “The Army Medical Department 1775-1818,” US Army Medical Department Office of Medical History, Army Historical Series, 56, history.army.mil/html/books/030/30-7-1/index.html.

[9]General Orders, July 4, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0027.

[10]Washington to John Hancock, December 14, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0503.

[11]Becker, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army,” 402.

[13]General Orders, May 26, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0312.

[14]J.L. Bell, “Thereby prevent Inoculation amongst them,” boston1775.blogspot.com/2021/05/thereby-prevent-inoculation-amongst-them.html.

[15]“A Deadly Scourge: Smallpox During the Revolutionary War,” www.armyheritage.org/soldier-stories-information/a-deadly-scourge-smallpox-during-the-revolutionary-war.

[17]Becker, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army,” 393.

[20]Elizabeth Fenn, “The Great Smallpox Epidemic,” History Today Volume 53 Issue 8 (August 2003).

[21]Washington to Hancock, December 11, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0487.

[22]Washington to Phillip Schuyler, June 7, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0363.

[23]James Kirby Martin, Benedict Arnold – Revolutionary Hero (New York: New York University Press, 1997),163.

[24]Becker, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army,” 403-404.

[25]William Shippen to Washington, January 25, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0163.

[26]Washington to Shippen, Jr., January 28, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0182.

[27]Washington to Horatio Gates, January 28, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0180.

[28]Washington to Hancock, February 5, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0268.

[29]Washington to Shippen, February 6, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0281. Fenn’s book, referencing this letter from an earlier compilation of Washington’s writings, identifies it as having been written on January 6, 1777, changing the sequence of events as she describes it. In Founders Online, a footnote indicates that at one point the transcript was inadvertently dated “Jany 6th.” by the copyist. I am assuming the more recent transcription, bearing the February 6 date, is correct.

[30]Journals of the Continental Congress, February 12, 1777, memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00739)).

[31]Continental Congress Medical Committee to Washington, February 13, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0349.

[32]John C. Fitzpatrick, ed.,The Writings of Washington, Volume 11 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1934), 182.

[34]F. Fenner et al, Smallpox and Its Eradication (Geneva: World Health Organization,1988), 240.

5 Comments

Awesome article. Military leaders then and today have such widespread responsibilities.

Years ago I had read it was literally the local “milkmaids” near Jenner’s house whom he observed hardly getting the disease, and that triggered his life-saving vaccine work. Vacca meaning ‘cow’ of course :).

Great article. I have a special interest in the medical aspect of the war because my ancestor was sick for a good portion of it. Many of the Valley Forge encampment muster roles have him sick at either Goshen or New Windsor. He was also treated by a Dr Jacob Everitt (Yacob Ebarth) on the banks of the Delaware River in 1781 which included venesection (blood letting). If you have any suggestions where I can learn about hospital camps at Goshen and New Windsor in 1778 I would love to learn more about what he went through. Several other sick soldiers had their condition listed on the muster rolls including small pox so my thought is it was something else. 🇺🇸

There is a Martha Washington angle to this story as well. She spent a portion of every winter of the war (all eight of them) in the company of George. The 1st Morristown winter if 76/77 was almost an exception, however. He told her only to come as far as Philadelphia and he would join her there, as there was a horrible epidemic of the pox then in the camp. This she did, but while in Philadelphia she got herself inoculated. Washington initially tried to forbid this but to no avail… her standing in that relationship was at least on par with her husband, in fact her personal wealth was greater than his. Some days later she informed George of her defiance in a letter. “Ah, I’ve lost my poor Martha” he exclaimed to his staff after reading it, fully expecting her not to survive the experience. Silence followed. A few weeks later she wrote again that she had endured the procedure and was doing fine. Overjoyed, Washington gave her the all-clear to join him in camp. So, according to this story (which is probably very difficult to verify since almost all the correspondences between Martha and George were burned by her after his death) it was Martha who was the one to ultimately sway George in favor of inoculation over quarantine as the preferred remedy.

I’m looking for information about inoculations at the Yellow Springs Hospital, near Valley Forge, from January to June 1778. My understanding is that they were done under the direction of Dr. Bodo Otto but I have not been able to find any detailed documentation.

Thank you for any leads.

https://books.google.com/books?newbks=0&id=dCJCAAAAIAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Yellow+springs+hospital+1778

Bibliographic information

QR code for Dr. Bodo Otto and the Medical Background of the American Revolution

Title Dr. Bodo Otto and the Medical Background of the American Revolution

Author James Edgar Gibson

Edition illustrated

Publisher C. c. Thomas, 1937

Original from the University of California

Digitized Oct 11, 2007

ISBN 0398042659, 9780398042653

Length 345 pages

Get this book on Dr. Bodo Otto. Google has a scan copy on-line with 37 pg hits (1778 Yellow Springs)