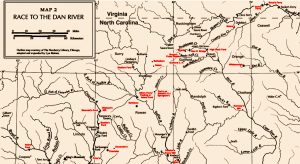

The Race to the Dan is a famous part of the Southern War of the American Revolution, a strategic retreat by Gen Nathanael Greene, that once across the Dan River, allowed the Southern Army to regroup and resupply. Ten days later Greene recrossed the Dan, was reinforced and on March 15, 1781 fought the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, a pyrrhic victory for the British that severely weakened the British army leading to the Yorktown surrender October 19, 1781.

From early January to mid-March of 1781, General Greene played a “catch me if you can” game with Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis, moving northward through the Piedmont of the Carolinas to the Dan River and Virginia where supplies and militia were promised. From Cowpens, South Carolina to the Dan River crossing, Greene separated, moved and reunited his army in a strategic retreat. At various points Greene attempted to rally sufficient militia and supplies to do battle but was frustrated each time by the poor response to his pleas. After his army was reunited at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, on February 8, Greene turned his sole attention to getting his prisoners, stores, and men into Virginia.

As Greene assembled his army from February 5 to February 8, Cornwallis moved west of Guilford Courthouse, crossed the Yadkin River at the Shallow Ford and moved into the Moravian villages twenty-five miles west of Guilford. By February 10 Cornwallis and his army were camped four miles east of Salem, the largest of the Moravian villages on the Friedrich Müller plantation. He was convinced Greene had to move to the upper fords of the Dan River to cross and that being near Salem he was in a position to cut Greene off before crossing. But he was unaware that Greene had his men marshal boats for crossing down river near present day South Boston, Virginia. And to assure his crossing Greene detached 700 men under the command of Col. Otho Williams, including Lt. Col. Henry Lee’s cavalry, to screen his movement, slow the British march and add credibility to Cornwallis’s belief that Greene had to cross at the upper fords. The last of Greene’s forces crossed the Dan late on February 14, beating Cornwallis’s advanced troops who arrived at the Dan River the morning of February 15.

Historians focusing on the two key battles before and after the Race to the Dan—Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse—often pass over the February 11-15 period with limited detail and treat it as one continual period of hard marching and skirmishing.[1] But if one examines various primary sources such as the Nathanael Greene papers, orderly books, and journals, a very different picture emerges. After strenuous marches from the Yadkin River fords near Salisbury and the Cheraw Hills, both armies paused to rest their troops, gather intelligence and determine their next moves. February 11 and 12 were essentially pauses by both armies as Greene and Cornwallis tried to make use limit information to determine their tactics. Once decided, February 13 and 14 for Greene and Williams and February 13, 14, and 15 for Cornwallis were marked by very rapid, exhausting marches usually portrayed as characteristic of the Race to the Dan.

One event during this period that does get noticed is what I will call the Bugle Boy Skirmish. Two and one half miles west of Bruce’s Crossroads (now Summerfield, North Carolina) Lee and a troop of his dragoons met the van of Cornwallis’s army in a small skirmish that resulted in as many as eighteen British dragoons killed but only one casualty for Lee—a bugler named James Gillies, a young boy who was sabered to death by the reputedly drunk British dragoons.

The specifics of the event near Bruce’s Crossroads come down to us from three primary sources. The most detailed is Lee’s memoir written about thirty years after the event.[2] The second is Alexander Garden’s account, very likely second-hand information from those who were there, notably Peter Johnston;[3] Garden joined Lee’s Legion later in the war but served with many of the men who had been at Bruce’s Crossroads. The third is that of Eli Caruthers in his 1856 Revolutionary Incidents.[4] This was written long after the event and relied on an account from the Rev. Henry Tatum, Charles Bruce’s son-in-law, whose 1807 home was a few hundred yards from where the event occurred. Tatum’s account was no doubt drawn from those of his father-in-law Charles Bruce and his neighbors, so it is also second hand from those who observed the event. All three accounts vary a bit but provide the same basic narrative.

Williams’ light troops began to fulfill their screening mission by moving to Bruce’s Crossroads. His men had begun to prepare their main meal of the day around noon when a local farmer, Isaac Wright, rode in on a broken-down horse. Wright reported that he saw the British Army from his fields only a few miles west of where Lee’s men were preparing their meal.

This revelation was at odds with Williams’ intelligence, so he ordered Lee to investigate. Lee sent Capt. James Armstrong and a couple of his dragoons with Wright to investigate. After a few minutes Lee decided he and a troop of dragoons should go, sent a messenger ahead to stop Armstrong, joined him, and then rode further without encountering the British. He then decided Wright was wrong about the distances and turned around to get his men back to their meal. To avoid surprise, he sent a lieutenant and Wright further up the road. Wright objected to going on a poor mount, especially with only one dragoon for protection, so Lee had his bugler, James Gillies, exchange horses with Wright. Lee then sent Gillies back to Williams to report their position and their failure to encounter the enemy. But within a few minutes shots signaled the scouts had found British troops. Lee took his troop into the woods along the roadside, and unseen by the British he watched Wright’s party gallop by, then the British dragoons in pursuit. Lee waited a bit to determine if additional British were coming but when none appeared he rode after the enemy. In a short time he came upon the dragoons who had caught up to the slow-moving Gillies and were sabering him to death. Lee immediately ordered his men to charge. They killed all but a couple, including the British captain, who were captured and sent on to Williams. Furious that the British did not give quarter to the “beardless boy,” Lee considered executing the captured British captain. Before he could do so, the rest of the British van came up, and Lee and his dragoons escaped, riding east to rejoin Williams.

Local lore passed down through the years has the Bugle Boy Skirmish occurring on February 12 when the American light troops stopped at Bruce’s to cook their main meal of the day prior to the skirmish. After the skirmish the British Army moved up and camped at Bruce’s.[5] But an examination of Greene’s papers offers strong evidence the date of the Skirmish was February 11, not February 12. And if the Skirmish occurred on February 11, it is very likely that the movement of the British Army was different than usually assumed and that the Skirmish conveyed important information to Cornwallis, Williams and Greene about the tactics of their foes.

The best evidence for the Bugle Boy Skirmish being on February 11 is Williams’ two dispatches to Greene dated February 11.[6] The first came from a camp seven miles northwest of Guilford Courthouse, the location of Bruce’s Crossroads, as confirmed by Tarleton, by Lee, and by Johnston in the Alexander Garden anecdote, and from local lore. At 9:00 a.m. Williams reported to Greene that he learned Cornwallis was six miles from Salem on the afternoon of February 10, but was unsure of the enemy’s route and would “search diligently for them.”

At 3:00 p.m., again on February 11, a dispatch was sent by Williams to Greene from “on the march” near Rhodes, describing his attempt to ascertain Cornwallis’s route and distance. He noted an “accident informed him” of the closeness of the British van and concluded that “Tarleton and whole British army is close to our rear.” He also reported that he had his troops on the move and they were crossing the Haw River bridge.

The “accident” was very likely Isaac Wright’s arrival at Lee’s position, but Williams’ dispatch was probably left vague so as to not highlight the surprise Wright provided, given the failure of Williams’ other scouts to locate the British. He then described Lee’s encounter with the enemy. The degree of the surprise was revealed in an 1834 Salisbury newspaper obituary of James Martin, colonel of the Guilford County Militia.[7] Martin and some of his militia men accompanied Williams and Greene in the Race to the Dan. The obituary was written by Hamilton Jones, a stepson of James Martin, so likely a repetition of an eyewitness account. Jones reported that Lee did not believe the farmer’s information and insulted the farmer. Wright was defended by Martin, who encouraged Williams to send Lee to investigate despite Lee’s objections. Lee’s disparagement of Wright may indicate that he and his scouts should have detected the British van moving up from Dillon’s Mill to Bruce’s along what is today North Carolina route 150 but did not. This is plausible if he was scouting the main British army to the south of Williams’ light troops. Williams went on to report that “Col. Lee met the Enemy’s advance, stood a Charge and Captured 3 or 4 Men whom I send to you.”

How can we be sure that the February 11 dispatches were referring to the Gillies incident? No mention is made of the fate of James Gillies in Williams’ second dispatch. First, we have Lee’s account, though clearly misdated, in which he went into great detail regarding the encounter and located it near Bruce’s Crossroads. Caruthers also reported the encounter as being near Bruce’s, based on stories by Reverend Tatum and others. Finally, Alexander Garden’s recounting of the 1826 meeting of Johnston and Bruce at Bruce’s Crossroads makes it very clear the event occurred near Bruce’s.[8] No other encounter was reported.

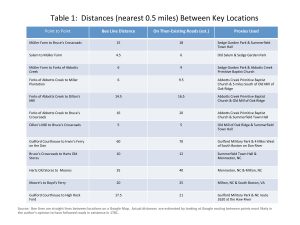

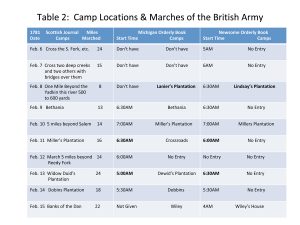

If we accept February 11 as the accurate date of the Bugle Boy Skirmish, what were Cornwallis’s movements on February 11 and 12? Table 1 is a comparison of camp locations and mileage from two orderly books and a journal in the papers of a Scottish officer of the Brigade of Guards; this will be referred to here as the Scottish journal. Caruthers in his 1856 Sketches appended what he called the Cornwallis Orderly Book, which was republished by A. R. Newsome in 1932 in the North Carolina Historical Review. It is an orderly book for the Brigade of Guards which includes general orders given by Cornwallis as well as brigade-level orders. It is often cited as the Cornwallis Orderly Book, but it lacks an entry for February 11. The William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan holds a different orderly book containing only Cornwallis’s general orders, which does have an entry for February 11 as well as some other key differences discussed below. To avoid confusion I will refer to the first orderly book as the Newsome orderly book and the second as the Michigan orderly book.[9]

The Michigan orderly book identified Cornwallis’s February 11 camp as being at the “Crossroads.” Someone wrote “Bruce’s” on the manuscript in ink and in a script different from the original. Some locations written in to help locate the camps are illegible, and a few that are legible agree with the Newsome orderly book.

Camping at Bruce’s is plausible if one assumes the British Army marched directly from Salem with no deviation. The distance from Müllers to Bruce’s Crossroads is about eighteen miles (see Table 1). The Scottish journal has the army marching sixteen miles on February 11 which means, given what we know was a spread out army camp on February 10, British soldiers could well have camped at Bruce’s or at Dillon’s, where the mill would have provided food plus an open area for camping. No doubt this calculation was important to the long-standing popular view that the British Army camped at Bruce’s on February 12 and the Bugle Boy Skirmish happened earlier in the day.

But did Cornwallis march directly from the Müller plantation without deviation, therefore being able to camp at Bruce’s the night of February 11? This is doubtful, at least for the entire army. Historians Laurence Babits and Joshua Howard argue that in the morning of February 11 Cornwallis marched southeast, not north-northeast toward Bruce’s.[10] He got as far as the Abbotts Creek community and then turned north toward Bruce’s. According to Babits and Howard, Cornwallis had intelligence that the main part of the American Army under Gen. Huger coming from the Cheraw Hills in South Carolina had not yet reached Guilford Courthouse, and that he might be able to cut them off and bring them to battle. But Babits’ and Howard’s reference to the Newsome orderly book only provides the time andorder of march, not direction. The same is true for the Michigan orderly book.

It is known Greene’s papers that part of Huger’s force, Colonel Smith’s regiment and Lee’s Legion, were behind the main army as Huger marched to Guilford. Huger arrived on February 7, two days after Morgan. Huger sent a “at sunrise, February 8” report to Greene that had Lee’s cavalry two and a half miles north of Bell’s Mill, roughly twenty miles from Guilford Courthouse. If the Huger report was accurate Lee could not have arrived until late on February 8 or early on February 9.[11] Perhaps that was the intelligence Cornwallis received the evening of February 10. It is also true that Greene, after failing to muster sufficient militia to take on Cornwallis near the Trading Ford on the Yadkin, moved with a small force to the Spurgeon plantation near the Abbotts Creek Meeting House. He was there for the nights of February 6 and 7 trying to determine Cornwallis’s location and direction of march. Finally, in the early morning hours of the 8th, he learned Cornwallis was crossing at the Shallow Ford and immediately set out for Guilford Courthouse, arriving there later that day.[12] Did Cornwallis have intelligence that Greene was at Abbotts Creek and he thought he could capture Greene?

Another explanation of why Cornwallis may not have followed a direct route to Bruce’s is by Greene biographer William Johnson. He argues that Cornwallis undertook a “ruse de guerre.” According to Johnson, Cornwallis believed that if he moved southeast he could threaten Hillsborough, which had large stores for the American Army and was central to Whig governance.[13] Throughout Greene’s dispatches for this period, Greene showed great concern for the stores at, and coming to, Hillsborough and their safe evacuation into Virginia. While I can find no evidence for this feint in British sources, Greene issued letters on February 11 that are instructive.

On that day Greene sent three letters to Col. John Gunby, who was in charge of the stores at Hillsborough, and one to militia Gen. John Alexanger Lillington.[14] The letter to Lillington was sent from Reedy Fork Creek and said Greene had recent intelligence the British were marching toward Guilford Courthouse. Later in the day in a letter to Gunby sent from near the Haw River bridge he said he had reliable information the enemy was moving toward Hillsborough and directed all stores there to be removed. Finally in two later dispatches to Gunby from the “Camp three miles north of the Highrock Ford” Greene stated that Cornwallis was on his way to Guilford Courthouse, which could mean on the way to Hillsborough. All dispatches show great concern for losing the stores at Hillsborough. It appears Greene was well aware that a British movement southeast could threaten both the Southern Army and its supply base at Hillsborough, but he did not fall for the “ruse de guerre.” Instead he stayed with his plan to move the main army to the lower Dan River ferries and screen his move with Williams’ Light Troops. This decision was no doubt made easier by his orders to evacuate stores well in advance of the February 11, as he reported to General Washington.[15]

In 1980 local historian Fred Hughes produced a map entitled Guilford North Carolina Historical Documentation.[16] The map shows the location of landowners as of February 1781, the source of their land acquisition, along with roads, churches, mills and other landmarks. It also shows the camps and routes of both Greene’s and Cornwallis’s armies. On the Hughes map, Cornwallis’s February 11 encampment is located at the junction of the Moravian Town Road and Hunt’s Road (road names are those used by Hughes). The junction is approximately five miles south of Dillon’s Mill, a simple tub mill located on Beaver Creek across what is now North Carolina route 68 from the present-dayOld Mill of Oak Ridge, two miles south of present-day Oak Ridge. The mill in turn is five miles southwest Bruce’s Crossroads. On the Hughes map, landowner Joseph Miller is located at the Moravian Town Road and the Hunt’s Road crossroads. The Scottish Journal lists the camp on February 11 as at Millers Plantation. The Michigan orderly book simply says Crossroads and there is no entry in the Newsome book for February 11. The Michigan orderly book scribbler, no doubt, immediately took Crossroads to mean Bruce’s Crossroads, but it could just as well have been the crossroads near the Miller Planation some ten miles southwest of Bruce’s.

Although local lore has the entire British army camping at Bruce’s Crossroads on the 12th, local historian Kate Hoskins reported British as being O’Hara’s forces, the British van, not the entire British Army. In her writing she is very specific that O’Hara’s Brigade of Guards were at Bruce’s plantation and burned his fences and outbuildings. Only by the intercession of his Quaker neighbors was his home saved from the torch. Charles Bruce, a strong and, to the British, notorious Revolutionary had moved his family to relatives and marched north with Williams.[17]

If Hoskins is correct, on February 11 Isaac Wright saw a British force of about 800 infantry and cavalry belonging to the British Legion and Brigade of Guards. Lee ran into the very tip of that force when he responded to Wright’s warning. If true, then Cornwallis’s forces were spread out over twenty miles as Cornwallis was making his turn north at Abbotts Creek and Tarleton’s Dragoons were ending James Gillies’s life. It is also possible that the timing was such that the Gillies encounter was the event that convinced Cornwallis that his ruse was not working, and that Greene’s army was moving to the upper fords of the Dan as he had expected based on the intelligence he had been getting for days.

We know from both orderly books that Tarleton and the Guards formed the van, and Leslie’s orderly book shows this to be the rotation ordered on the evening of February 10. Lee noted the need for Cornwallis to slow his advance “to give time for his extended line to condense.” Moravian reports indicate that it took the British six hours to march through Salem on February 10, that it was a desultory march, and that the camp that night spread out over two and one half miles, from Müller’s farm on to the Love farm. Moravian records also report heavy drinking by the British Army on both February 9 and February 10.[18]

On the evening of February 10 Cornwallis knew that Greene was at Guilford Courthouse. He did not know that Greene had already started to move his men north that morning, but he believed that if and when Greene moved it must be in a northward direction to get to the upper Dan River fords. Did he make his feint with part of the army and send the van of Tarleton and the Guards north to cut off Greene if Greene ignored his feint and moved north? According to the Newsome orderly book, the march on February 11 was scheduled for 6:00 a.m. If Cornwallis marched towards Abbotts Creek, it would have taken him about five to six hours using a marching speed of a bit less than two miles per hour. This would have put them with no delays at Abbotts Creek somewhere between 11:00 a.m. and noon if indeed they made it that far. The Bugle Boy Skirmish was over by 2:00 p.m. according to Williams’ 3:00 p.m., February 11 dispatch, and that occurred about twenty miles from the Abbotts Creek area. Reconnoitering time at various points and other delays could have put the main part of the British Army at Abbotts Creek in the early to mid afternoon. If so, a galloping courier could have gotten word to Cornwallis that his van had engaged Greene’s army at Bruce’s Crossroads. In response Cornwallis turned north and the remaining six miles of the Scottish Journal’s sixteen mile march for February 11 would have brought him to Miller’s Plantationwhere he camped.

Another piece of evidence suggests Cornwallis hedged his bets by splitting his forces. Lee in his memoirs reported that Cornwallis “ordered his van to proceed slowly; and separating it from the main body, which had now arrived at a causeway leading to the desired route, he quickly gained the great road to Dix’s Ferry, the course of the American light troops.” The Scottish Journal has Cornwallis marching fourteen miles and camping five miles beyond the Reedy Fork on the February 12. The Scottish Journal could have Cornwallis crossing the Reedy Fork about a mile south of Dillon’s Mill. But five miles beyond this crossing would have been too short a march if they did camp at Miller’s plantation. It is more likely that the Scottish Journal refers to a different crossing of the Reedy Fork. If, as Lee reported, Cornwallis took a more easterly road on February 12 it may have been the precursor to present day Bunch Road, which crosses the Reedy Fork, or another more southern road. A more southern route would not have crossed the Reedy Fork but would have put him on the New Garden Road (now Pleasant Ridge Road) into Bruce’s which does cross the Reedy Fork. Five miles beyond following Williams on “the great road to Dix’s Ferry” (likely present day Scalesville Road) would have put Cornwallis near the Haw River crossing. Also, the Lee’s reference to Cornwallis coming in behind Williams would be consistent with reaching the New Garden road about two miles south of Bruce’s Crossroads.

If we extend this narrative, Cornwallis marched through Bruce’s Crossroads on February 12, eventually camping within a few miles of present day Monroeton and the old Speedwell Iron Works. Interestingly, one of the illegible scribbles on the Michigan orderly book is for the 12th, and what can be read of it appears to say “near Iron,” and the last word could well be “works.”

After February 12, the relatively modest marches of February 11 and 12 (sixteen and fourteen miles) gave way to long marches of twenty-four, eighteen and twenty-two miles for the next three days, according to the Scottish Journal. The length of those marches, the Williams correspondence with Greene, and the descriptions by Lee and others involved in the Race to the Dan, demonstrate the helter-skelter nature of the final three days of the race. Camps were not really camps, only stops for a few hours sleep before continuing to march. The van of Cornwallis’s forces was oftenin sight of Williams’ rear guard, occasionally exchanging fire. By midnight on February 14 the race had been won by Greene, but by only a few hours.

Although we can’t be absolutely sure of the role played by the Bugle Boy Skirmish in the Race to the Dan, it appears that it may have been more significant than previously recognized. The records indicate that, on February 11 and not February 12, the dragoons of Lee and Tarleton skirmished. It was a wakeup call to Williams that the British were close on their heels, that the last leg of the race had begun, and it was time to get moving to lure Cornwallis north now that he had taken the bait offered by Williams and his light army. To Cornwallis it may well have signaled that Greene was not falling for his feint, and that Greene was at Bruce’s Crossroads moving, as he had expected, to the upper portions of the Dan River. It was time to form up his dispersed troops for battle and move on to Bruce’s Crossroads. The final leg of the Race to the Dan may well have been triggered by a seemingly inconsequential skirmish that cost the life of a young American bugler now honored in his final resting place in the Charles Bruce family cemetery in Summerfield, North Carolina.

[1]Representative of this treatment is John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997), 354-58. A more recent study which focuses on the Race to the Dan goes into greater detail but is confusing, to this author, as to dates and movements apparently due to treating Lee’s discussion of events in his memoirs as being chronologically accurate, although the author concurs with the February 11 date discussed in this article having consulted the same primary sources. Andrew Waters, To the End of the World: Nathanael Greene, Charles Cornwallis and the Race to the Dan (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2020), Ch. 14.

[2]Henry Lee, The Revolutionary War Memoirs of General Henry Lee Edited by Robert E. Lee (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), 239-43.

[3]Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the American Revolution (Charleston: H. E. Miller, 1828), 117-19.

[4]E. W. Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Characters (Philadelphia: Hayes and Zell, 1854), 46-48.

[6]Richard K. Showman and Dennis M. Conrad, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, Volume VII (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 282-283.

[7]Obituary of James Martin, Salisbury Carolinian, November 15, 1834.

[8]Garden, Anecdotes, 119-120.

[9]The Scottish Journal is part of the Leslie family papers in the National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh; a copy is in North Carolina archives which is referenced here. There is no author given but its association with Gen. Alexander Leslie suggests it was likely compiled by his adjutant or someone in the Brigade of Guards since the remainder of his force that joined Cornwallis on the 28th of January was Hessian. The Newsome orderly book is well known. The Michigan orderly book a manuscript and was acquired by the Clements Library in 1977.

[10]Lawrence E. Babits and Joshua B. Howard, Long Obstinate and Bloody; the Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 31-32.

[11]The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 254 (Morgan) and 259 (Huger).

[13]William Johnson, Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States, Volume 1 (Charleston, S.C.: A.E. Miller,1822), 427-32.

[14]The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 280.

[16]The Hughes map is no longer in print but is available at the University of North Carolina Library.

[17]Katherine Hoskins, “Charles Bruce: A Friend of Liberty,” Greensboro Daily News, July 1, 1931.

2 Comments

A lot of meticulous research for this article…thanks for your good work!

Excellent article. I live in the area and often talk to friends about the skirmishing along the routes. This provides great context. So much is focused on the battles that often the movements get short attention.