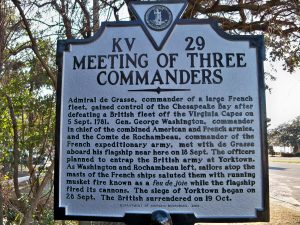

On March 6, 2019, a chilly late winter afternoon, the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission dedicated a Virginia Historical Highway Marker to commemorate a historic meeting of three commanders. On September 18, 1781, Adm. François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, Gen. George Washington, and Gen. Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, met on board de Grasse’s ninety-gun flagship Ville de Paris anchored off shore near the location of the marker. Gathered for the dedication ceremony were the Mayor of the City of Virginia Beach, Bobby Dyer, French Air Force General André Lanata, Supreme Allied Commander for Allied Command Transformation (ACT), North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and many others from the local Hampton Roads communities. Virginia Beach resident Jorja Jean researched and developed text for the marker. The meeting of the three commanders, an important event in the history of the American Revolution deserving of recognition, took place at anchor in the waters called Lynnhaven Roads. The marker is located just east of the Lesner Bridge that spans the Lynnhaven River Inlet, along Shore Drive, a main thoroughfare that parallels the North Shore of Virginia Beach adjacent to de Grasse’s Lynnhaven anchorage.[1]

Today, Lynnhaven Roads is an important anchorage for military and commercial ocean-going vessels entering the Chesapeake Bay as they wait for pier space. Located only a few miles from Cape Henry at the mouth of the bay, the spot where the 1607 English settlers landed to establish the first permanent English colony in the New World, Lynnhaven Roads also played an important role during the American Revolution. This was the primary anchorage selected by Admiral de Grasse for the French fleet during the Yorktown Campaign of 1781. While the objective of the allied campaign may have been in question until the arrival of the French fleet in the Chesapeake Bay, Washington understood that the military success of the American Revolution in 1781 depended heavily on French military and financial support. Specifically, Washington understood the importance of the French fleet in countering British naval power. He outlined his thoughts in a letter to General Lafayette a year earlier as elements of the French fleet arrived, accompanied by Rochambeau’s expeditionary land forces, at Newport, Rhode Island.[2]

On May 1, 1781, General Washington reiterated his understanding of the importance of naval power and noted in his diary, “instead of having the prospect of a glorious offensive campaign before us, we have a bewildered, and gloomy defensive one—unless we should receive a powerful aid of Ships, Land Troops and Money from our generous allies & these, at present, are too contingent to build upon.”[3] By September 1781, Washington had all three key ingredients needed for a successful offense, warships, land troops and money, provided by his French allies. The meeting of the three commanders allowed the key allied decision makers an opportunity to meet face-to-face and finalize plans for the siege of Yorktown.

Washington and Rochambeau had since August been quickly moving Franco-American land forces from the Hudson River Valley south to engage British forces in Virginia. In early September, de Grasse challenged a powerful British fleet for control of the seaward approaches to the Chesapeake Bay. What followed would become known as the Battle of the Capes, sometimes referred to as the Second Battle of the Capes, a critical action that left the French navy with complete local naval superiority.[4] By September 11 the French held the Chesapeake Bay with over thirty ships of the line, able to deliver heavy siege guns and supplies and provide transports to move troops by water that Washington and Rochambeau needed to win ashore.[5] As the land forces assembled near Williamsburg, Washington and Rochambeau boarded a small sailing vessel bound for a meeting with de Grasse that would produce positive results yet unexpectedly keep the commanders away from their forces for five days.[6]

On September 17, 1781, Washington, Gen. Henry Knox, Gen. Louis Duportail, aides Cols. David Cobb and Jonathan Trumbull, and Rochambeau and his deputy Gen. François-Jean Chastellux, boarded a captured British vessel now in French service, Queen Charlotte, for travel to Ville de Paris. Proceeding down the James River they passed several ships likely engaged in offloading troops, supplies and siege canon at several landing sites on the south shore of the James. Spending a comfortable night on board, the wind and tide cooperated during the morning of September 18 when they entered de Grasse’s anchorage “just under the point of Cape Henry” and proceeded to board the French flagship about noon.[7]The voyage was uneventful.

Washington prepared a list of six primary questions before the meeting and de Grasse answered each of these. In his responses, de Grasse grasped the significance of the developing circumstances and placed the events unfolding as having long-term global security and diplomatic implications when he stated, “The Peace & Independence of this Country & the general Tranquility of Europe will, it is more than probable, result from our completeness of success.” Astutely aware of his obligations to his Spanish allies and commitments in the West Indies, de Grasse indicated he could remain in the Chesapeake until November 1 but preferred to depart by October 15, taking with him 3,000 troops required in the West Indies. He would consider sending ships above Yorktown in the York River to observe British movements. He would provide 1,800 to 2,000 men for a “Coup de Main” and had the resources to furnish some cannon and a small amount of powder, but he would not support follow-on naval actions against Wilmington or Charleston.[8]

Although Washington hoped for more, his aide Colonel Trumbull indicated the meeting with de Grasse went extremely well. After the introductions, business was “proposed and soon dispatched to great satisfaction.” This meeting confirmed de Grasse’s naval commitments and set the desired conditions for the siege of Yorktown. Washington’s party was received by de Grasse “with great ceremony, and military [and] naval parade, and most cordial welcome.” Trumbull commented on Admiral de Grasse’s “size, appearance and plainness of address.” After dinner Washington’s party received a tour of the ship, described as “the world in miniature.” The group then exchanged greetings with many officers of the French fleet who came on board to meet Washington’s party. About sunset, they reboarded Queen Charlotte, receiving several “Feu de joys—or vive le Roy” from the fleet.[9]

The return voyage began with little wind and slow progress that evening and the morning of the 19th. The afternoon of the 19th produced a strong headwind forcing the ship ashore for the night. Impatient to return to their commands on the morning of the 20th, Washington and his party boarded the ships’ small boat, made their way to the twenty-six-gun frigate Andromaque for assistance, and enjoyed a breakfast meal. Returning to Queen Charlotte’s small boat they were soaked by spray before once again boarding the Queen Charlotte. Again driven ashore because of the headwind, they were visited by officers from the smaller vessels in the allied formation. Tacking against the headwind on the 21st they made slow progress, arriving at Williamsburg about noon on the 22nd.[10] During their absence Gen. Benjamin Lincoln had reported significant progress in assembling the army and unloading material, helping reassure that progress preparing the army continued during Washington’s five-day absence.[11]

Although Washington would need to continue to coordinate with de Grasse during the siege because of evolving information from intelligence reports, the siege progressed with the necessary naval support. The key commanders understood each others’ intent, a critical consideration in joint and coalition warfare.[12] Although Washington wanted to conduct follow-on operations with the French fleet, de Grasse had set his strategic priorities in coordination with the Spanish before departing to support operations in North America, requiring his return to the West Indies.[13]

It is appropriate that the historic marker commemorating the meeting of the three commanders, de Grasse, Washington, and Rochambeau, rests near the Lynnhaven anchorage where the French navy supported the land forces. Without this cooperation between French naval commanders and the land component commanders, the siege of Yorktown would never have occurred. Washington’s May 1, 1781 diary entry reflected his understanding that the 1781 campaign depended on French support. While Washington desired more from the French navy, he received just what he needed from both their army and navy to eliminate a significant portion of Great Britain’s offensive combat power.[14] The meeting of the three commanders finalized the details of the joint and coalition support that ultimately contributed to a successful campaign and led to the political conditions facilitating the end of hostilities and the birth of the United States as an independent nation.

[1]Joria K. Jean worked through the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission to approve and receive funding for a Virginia State Highway Marker to commemorate this event, www.vbgov.com/government/departments/planning/boards-commissions-committees/Pages/Research-Grant-Projects.aspx.

[2]Dudley W. Knox, Letter, Washington to Lafayette, July 15, 1780, reprinted in, The Naval Genius of George Washington (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1932), 64. “In any operations, and under all circumstances, a decisive naval superiority is to be considered as a fundamental principle, and the basis upon which every hope of success must ultimately depend.”

[3]George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, 1771–75, 1780–81, 3, The Papers of George Washington, Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1978), 356-357, tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/mss/mgw/mgwd/wd03/wd03.pdf.

[4]Charles Lee Lewis, Admiral DeGrasse and American Indepence(Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1945), 155-6; L. H. Landers, The Virginia Campaign and the blockade and siege of Yorktown 1781 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931), 165, babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027015323;view=1up;seq=3; De Grasse had about 1,800 troops and 90 officers ashore or engaged in landing operations and sortied his fleet while short these important personnel needed to properly man his fleet for combat.

[5]Karl Gustaf Tornquist, and Amandus Johnson, ed. & trans., The Naval Campaigns of Count de Grasse, 1781-1783 (Philadelphia: Swedish Colonial Society, 1942), 61.

[6]Jonathan Trumbull, “Minutes of Occurrences respecting the Siege and Capture of York in Virginia, extracted from the Journal of Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, Secretary to the General, 1781,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 14 (1875-76),332-333.

[7]Ibid., 334, Trumbull states the anchorage was sixty miles from the point of embarkation. Washington boarded Queen Charlotte on College Creek near Williamsburg

[8]Questions Proposed by General Washington to Comte de Grasse, September 17, 1781, The Writings of George Washington, 23 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1937), 122-125, archive.org/details/writingsofgeorge23wash/page/122/mode/2up; De Grasse’s responses are contained in Senate Document No. 211, Questions and Answers, Correspondence, 35-41.

[9]Trumbull, “Minutes,” 333-334. The American cause became an object of the French press, explaining the interest of the officers of the French fleet in meeting Washington, the man who led the army; see Julia Osman, Citizen Soldiers and the Key to the Bastille (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), 80-111.

[10]The timeline is based on the dates in Washington’s Diary, vice Trumbull’s “Minutes.” Washington to de Grasse, September 22, 1781, Washington, Writings, 127n. This letter is addressed from Williamsburg in the handwriting of Tench Tilman who did not accompany Washington, supporting Washington’s timeline.

[12]Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 1, Joint Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States (Washington: Department of Defense, March 23, 2013) V-15, “Commander’s intent represents a unifying idea that allows decentralized execution within centralized, overarching guidance. It is a clear and concise expression of the purpose of the operation and the military end state. It provides focus to the staff and helps subordinate and supporting commanders take actions to achieve the military end state without further orders, even when operations do not unfold as planned.”

[13]Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal of Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis during his commission which he had in his charge from 25 June 1780 until the 20th of that same month 1783 Francisco Morales Pardon, ed., Aileen Moore Topping, trans., (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989), 192, 196-213.

[14]Sir Henry Clinton had 32,000 troops in 1780 but required 14,000 to 17,500 to safely hold New York, with others committed to East Florida, West Florida and Georgia, limiting the forces available to employ in the Carolinas and Virginia. Ian Saberton, “Britain’s Last Throw of the Dice Begins: The Charleston Campaign of 1780,” Journal of the American Revolution, October 12, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/10/britains-last-throw-of-the-dice-begins-the-charlestown-campaign-of-1780/.

Recent Articles

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Trojan Horse on the Water: The 1782 Attack on Beaufort, North Carolina

This Week on Dispatches: Eric Sterner on How the Story of Samuel Brady’s Rescue of Jane Stoops became a Frontier Legend

Recent Comments

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...

"Those Deceitful Sages: Pope..."

Fascinating stuff. We don't always approach the American Revolution in its wider...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Scott....thank you, and indeed Dr Crow's work was a great help for...