“Captain John Bacon: His name was second only to that of the New Jersey devil for producing nightmares among the inhabitants of the pine barrens.”[1] As David Fowler, in his dissertation on Pine Robbers, noted: “John Bacon is the foremost Tory guerilla of the seacoast and pinelands regions.” He further stated that “Bacon is most representative of that manifestation of the Pine Robber phenomenon that witnessed a shift in Tory gang activity to the more remote, core areas of the pinelands in southern Monmouth and in eastern Burlington Counties.”[2]

In New Jersey, the region known as the Pinelands or Pine Barrens, is a one-million-acre section of the coastal plain that makes up approximately twenty-two per cent of the state’s area.[3] Adding to the attraction of this area for Loyalist Refugees were the barrier beaches and bays that served as bases of operations for smuggling of goods to and from New York; that activity was known as the London Trade. The London Trade was not limited to Loyalists: neutrals in the conflict and even Whigs were known to take part.[4] The present-day shore town of Tuckerton (then also known as Clamtown) was one of the centers of these smuggling operations.[5]

As with the activities of other Loyalist refugee raiders in the region, there is little in the way of primary sources concerning John Bacon; most of what we know about him is grounded in tradition, legends, and folklore. The consensus of historians is that Bacon most likely came from Arneytown, New Jersey, in Burlington County on the fringe of the Pinelands. He eventually moved to Stafford Township then in Monmouth County where it was said he was employed as a farm laborer and shingle maker.[6] He had a wife and two sons.[7] The first mention of John Bacon running afoul of the Whigs in New Jersey was an indictment in July 1780 by a grand jury: “did voluntarily and unlawfully go over to enemy held New York without a passport.” Fowler described the basis of this charge: “His career likewise provides an ideal example of the convergence of guerrilla activity and contraband trade by Tories during the latter part of the war.”[8] Bacon’s career as a Pine Robber began at this time. Interestingly, before this incident, there was no indication that he harbored Loyalist sympathies.

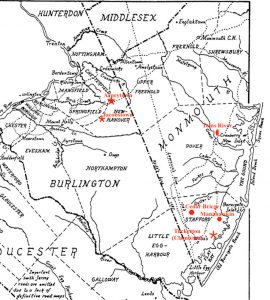

John P. Snyder, New Jersey Bureau of Geology and

Topography, 1969. Towns relating to John Bacon added

by author.

There were a number of raids in the second half of 1780 on Patriot homes in both Monmouth County (Forked River/Waretown area on Barnegat Bay) and Burlington County (Springfield Township) and while Bacon was not specifically identified, it was believed he either took part or led these attacks.[9] Then in December 1780 an incident took place that set in motion Bacon’s reputation as the most notorious Pine Robber. Appearing in the New Jersey Gazette of December 20, 1780 was the following notice: “We are informed that Lieut. Joshua Studson of Monmouth was shot last week, as he was attempting to board a vessel off Tom’s River, supposed to be trading from New York to Egg Harbour.”[10]

This incident occurred after three farmers, Asa Woodmansee, Richard Barber, and Thomas Collins, who though not Loyalists, had taken produce to New York City where the British paid in specie.[11] On their return, John Bacon, who was in New York, got them to take him aboard for the trip home. Entering Cranberry Inlet that led into Barnegat Bay opposite Toms River, they were hailed by a party of militia led by Lieutenant Studson.[12] Bacon, fearing that they were after him, fired and killed Studson. In the confusion surrounding Studson’s death, Bacon was able to make his escape.[13] Following this incident, Bacon and his gang most likely continued their plundering; however, it wasn’t until the following December that the next notice of Bacon comes in what is known as the “Skirmish at Manahawkin.”

On December 30, 1781, a contingent of Monmouth Militia from Stafford Township under the command of Capt. Reuben Randolph got word that Bacon and a group of Refugees were in the area on a raiding expedition. They set up an ambush for the raiders on the north-south Shore Road (today US Route 9) near Manahawkin. By 3 AM, with no sign of Bacon, the militiamen retired to Randolph’s tavern. At daybreak sentries spotted the raiders coming from the north and gave the alarm. Realizing they were outnumbered (believed to be thirty to forty Refugees), the militia fled the tavern with Bacon’s men firing at them, killing a militiaman named Lines Pangborn and severely wounding Sylvester Tilton.[14] As a result of this incident, John Bacon was indicted by the Monmouth Court for high treason.[15]

For most of 1782, Bacon continued raiding in the area of Barnegat Bay from Toms River to Little Egg Harbor: “Bacon used to visit the homes of well-known Patriots with his raiders taking whatever he wanted—money, food, and clothing, at the muzzle of a musket or point of a bayonet.”[16] In Edwin Salter’s History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, he details how Bacon and his gang invaded the homes of Patriots in the Forked River and Waretown areas, threatening the inhabitants with guns, bayonets, and knives. Salter further describes how the residents anticipated these raids, hiding and burying much of their money and valuables in the woods.[17] There is an interesting anecdote about the raids in this region:

James Wells (who lived near Waretown) was of Quaker origin and during the war. Having occasion to go off on some business, he put on the uniform coat of an American soldier which had been left at his house. This came near causing him to be killed, for the Refugee John Bacon saw him and was about to shoot him, when he discovered who it was. He was well acquainted with Wells and warned him not to try such an experiment again.[18]

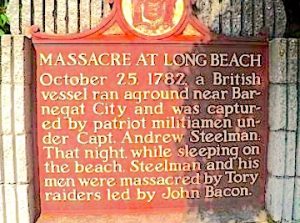

Then on October 25, 1782 occurred the event that solidified Bacon’s reputation as the most notorious of the Pine Robbers—the “Massacre of Long Beach Island.”[19] The only contemporary description of the events that led to the “massacre” come from a Loyalist source, the New York Royal Gazette. On Wednesday October 30 it noted:

Yesterday the Virginia ship of war, belonging to Messrs. Shedden and Goodrich, came of the Hook; she has taken a Cutter from Ostend bound to Virginia; Her cargo, from best information, cost £20,000 Sterling at Ostend—And what is very singular in this capture, Messrs. Shedden and Goodrich had intelligence from London, by a late packet, of this vessel’s sailing, and their friends mentioning a hope of the Virginia’s falling in with her, which has happened as they wished.[20]

Then three days later, there was a report about the fate of the ship and aftermath:

The cutter from Ostend, bound to St. Thomas’s, mentioned in our last, ran a-ground on Barnegat Shoals the 25th ultimo. The galley Allegator, Captain Stillman, from Cape May, with 25 men, plundered her on Sunday last of a quantity of Hyson tea, and other valuable articles; but was attacked the same night by Captain John Bacon, and nine men, in a small boat called the Hero’s Revenge, who killed Stillman, wounded the first Lieutenant, and all the privates (four only excepted) were either killed or wounded; the latter were sent to a Doctor, with a flag of truce, by the captors, and the galley was brought in here on Wednesday last.[21]

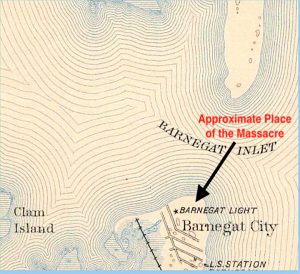

A ship with a valuable cargo of hyson tea, far off course, had been captured by British privateers and was on its way to New York. It ran aground on what was then called “Barnegat Shoals” (Barnegat Inlet at the northern end of the Long Beach Island) and abandoned.[22] The derelict ship was discovered by the Patriot privateer ship Alligator commanded by Capt. Andrew Steelman.[23] Captain Steelman landed his crew and began to salvage the cargo. He also sent word to the mainland to recruit men to help with the operation. The salvaging continued until dark when they set up camp.

While some of the salvagers returned home or back to Alligator, most remained on the beach for the night. Unknown to the Patriots was that Bacon supporter William Wilson heard of what was taking place on the island and sent word to John Bacon.[24] Bacon got together the crew of his privateer whaleboat Hero’s Revenge (estimated to be nine men), rowed across to Long Beach Island and attacked the sleeping men (around twenty-one) in the dark, mainly with knives and bayonets, killing Captain Steelman and most of the men (five were believed to have survived). When reinforcements sent from Alligator arrived on the scene Bacon’s men withdrew.[25] One result of the “massacre” was that Governor Livingston offered a £50 reward for the capture of Bacon.

Following the incident on Long Beach Island, it was believed that Bacon continued to operate along the Jersey Shore in both Monmouth and Burlington Counties. In the beginning of December, a party of Burlington militia were trying to locate Bacon and his gang to bring them to justice and collect the reward offered for their capture. Without success they returned home and then on Christmas Day resumed their search. The contingent, led by Capt. Richard Shreve, was composed of six light horse and twenty infantrymen.[26] On December 27, 1782, again with no luck in locating Bacon, they decided to return home. Upon arrival at Cedar Creek, they wanted to stop at the Cedar Bridge Tavern, but on the south side of the bridge spanning the creek, Bacon and his men had set up a blockade.[27]

There are various accounts of the ensuing fight; below is one from the New Jersey Gazette:

On Friday the 27th ult. Captain Richard Shreve, of the Burlington county light-horse, and Captain Edward Thomas, of the Mansfield Militia, having received information that John BACON, with his banditti of robbers, were in the neighbourhood of Cedar Creek, collected a party of men and immediately went in pursuit of them; they met them at Cedar Creek bridge; the refugees being on the South side had greatly the advantage of Captains Shreve and Thomas’s party in point of Situation; it was nevertheless determined to charge them: the onset on the part of the militia was furious, and opposed by the refugees with great firmness for a considerable time; several of them having been guilty of such enormous crimes as to have no expectation of mercy should they surrender, they were nevertheless on the point of giving way when the militia were unexpectedly fired on from a party of the inhabitants near that place, who had suddenly come to BACON’s assistance. This put the militia in some confusion, and gave the refugees time to get off. Mr. William Cooke, jun. son of William Cooke Esq: was unfortunately killed in the attack, and Robert Reckless, wounded, but is likely to recover—on the part of the refugees Ichabod JOHNSON (for whom government has offered a reward of £25) was killed on the spot: BACON, and three more of the party wounded.

The militia are still in pursuit of the refugees, and having taking seven of the inhabitants prisoners who were with BACON in the action at the bridge, and are now in Burlington gaol, some of whom have confessed the fact—They have also taken a considerable quantity of contraband and stolen goods in searching some suspected houses and cabins on the shore.[28]

From the above article and local histories, we can summarize that the Burlington Militia happened upon John Bacon and his Refugee gang at Cedar Creek Bridge and in the ensuing fight both sides suffered casualties, including the death of one of Bacon’s right-hand man, Ichabod Johnson, and most likely the wounding of Bacon. Probably the most interesting aspect of this encounter was the help Bacon received from locals. This might indicate that there was an undercurrent of Loyalist sentiment in the Pinelands and Bacon may have been “generous” in sharing the proceeds of his plundering with his part-time supporters.[29]

In February 1783, the British signed a treaty with France and Spain and called an end to hostilities in America, giving a de facto victory to the Patriots. As a result, many New Jersey Loyalists fled to New York City, the main area still under British control. It was believed that a number of Bacon’s followers went there, but for some unknown reason John Bacon chose to remain in the Pinelands. Most likely informed about his presence in the region, the Burlington Militia, not forgetting nor forgiving the deaths of their compatriots at Cedar Creek Bridge, continued their pursuit of Bacon.

Most accounts of John Bacon’s demise are based on a presentation by Dr. George F. Fort to the New Jersey Historical Society in 1846. He based his work on an interview with Charles Stewart of Cream Ridge, New Jersey, who was a son of American militia Capt. John Stewart. According to the account, Captain Stewart along with five men, including Joel Cook, a brother of William Cook who was killed at Cedar Creek Bridge, received a report that Bacon might be found at a “public house” owned by William Rose near West Creek on the Shore Road a few miles north of Clamtown (Tuckerton).

On April 3, 1783 they approached the building, looked through a window and saw John Bacon inside, holding a musket. Captain Stewart burst through the front door, knocking Bacon to the floor, whereupon Bacon called for “quarter.” With Stewart holding on to Bacon, Joel Cook entered and, seeing the man who was responsible to the death of his brother, bayoneted him in the back. After falling to the floor, Bacon got up and attempted to escape through the back door. After another struggle, Captain Stewart fired his musket, killing Bacon.[30]

The militiamen decided to take Bacon’s body to Jacobstown on the fringe of the Pinelands. As the party approached Jacobstown, the news of Bacon’s death and the presence of his body in the wagon spread and a crowd arrived to view the remains of the hated bandit. Supposedly the plan was to bury the body in the town’s crossroads so that all traces of his remains would be gone. But when a brother of John Bacon arrived on the scene and pleaded for the body, the authorities relented and gave the corpse to the brother, who took it to Arneytown where it was interred in the local Quaker cemetery.[31]David Fowler notes about this change of heart:

It is truly amazing that in a civil war that was characterized so much by vindictiveness, the citizens of Jacobstown, most of whom doubtless lived in fear of Bacon and several of whom had probably been victimized by him, exhibited mercy in the final hour. For indeed the final hour it was: John Bacon was the last person reported killed during the entire Revolutionary war.[32]

So ends the story of Capt. John Bacon, the “most notorious” of the New Jersey Pine Robbers.

In the months following Bacon’s death, claims were made for the rewards offered for the capture of him and other gang members. On June 9, 1783 the following resolution was proposed in the New Jersey Legislature:

A Petition from Captain Richard Shreve and Cornet John Brown, of the County of Burlington, was read, praying that an Order may pass to allow them and their Party the Reward offered by His Excellency’s Proclamation for securing Ichabod Johnson and John Bacon;

Whereupon, Resolved, That the Treasurer of the State be directed to pay unto Captain Richard Shreve, of the County of Burlington, the Sum of Twenty-five Pounds, in consequence of His Excellency’s Proclamation, being for the Use of himself and the Party of Men that assisted him in securing Ichabod Johnson; and to John Brown Cornet of Horse, of the said County, the Sum of Fifty Pounds, in consequence of said Proclamation of His Excellency, being for the Use of himself and the Party of Men that assisted in securing John Bacon; and the Receipt of the said Richard Shreve and John Brown, shall be sufficient Vouchers to the Treasurer for so much of the publick Money in the Settlement of his Accounts.[33]

[1]Steven Davidson, The Pine Barrens: The Cedar Bridge Affair, Loyalist Trails UELAC Newsletter, November 12, 2012. The Jersey Devil is a Pinelands legend based on the folktale story of a distraught mother, upon learning that she was expecting her thirteenth child, exclaimed, “let it be the devil.” In 1938 it was designated as New Jersey’s official “demon.” For an overview see: Jersey Devil and Folklore, Pinelands Preservation Alliance, pinelandsalliance.org/learn-about-the-pinelands/pinelands-history-and-culture/the-jersey-devil-and-folklore/.

[2]David Fowler, Egregious Villains, Wood Rangers, and London Traders: The Pine Robber Phenomenon in New Jersey During the Revolutionary War, Ph.D. Dissertation Rutgers University, 238. Fowler’s work is excellent and a very comprehensive history of New Jersey’s Pine Robber Phenomenon. For an account of the Pine Robber activity in areas bordering the Pine Barrens see: Joseph E. Wroblewski, “Loyalist ‘Banditti’ of Monmouth County, NJ: Jacob Fagan and Lewis Fenton,”Journal of the American Revolution,June 10, 2021.

[3]In 1978 the United States Congress established the Pinelands National Reserve; in 1979 Gov. Brendan Byrne signed New Jersey’s Pinelands Preservation Act.

[4]For a good description of the London Trade see Fran Leskover, The Setauket Gang: The American Revolutionary War Spy Ring You’ve Never Heard About (University of Puget Sound, Summer Research, 2019), 26, soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research.

[5]Ironically, in the same area Little Egg Harbor, the Mullica River and the port of Chestnut Neck served as centers for Patriot privateering activity.

[6]Most of the area that John Bacon operated in today is in Ocean County, formed in 1850 from parts of Monmouth and Burlington Counties.

[7]Henry Charlton Beck, More Forgotten Towns of Southern New Jersey (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 7th Printing, 1963), 260. At the height of Bacon’s depredations, it was reported his wife resided in Pemberton, Burlington County.

[8]Fowler, Egregious Villains, 238, 241. Two other Pine Robber gang leaders who operated contemporaneously with Bacon the Pinelands heartland were William Giberson, Jr. and Joe Mulliner; for their exploits see: Fowler, Egregious Villains,Chapters 4 and 7.

[9]For a review of Bacon’s activities during this time see Edwin Salter, Historical Reminiscences of Ocean County, New Jersey(Toms River, NJ: New Jersey Courier, 1878), 3. Ben Ruset, “The Refugee John Bacon,” www.njpinebarrens.com/the-refugee-john-bacon/. Fowler, Egregious Villains, 242.

[10]“New Jersey Gazette,” Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey,” vol. V, Newspaper Abstracts, October, 1780 – July, 1782, Austin Scott, ed., (Trenton: State Gazette Publishing Co. 1917), 145. The correct spelling is Toms River, no apostrophe.

[11]Edwin Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, Embracing Genealogical Records (Bayonne, NJ, E. Gardner and Son, 1890), 203.

[12]The Cranberry Inlet no longer exists, it was closed by a hurricane in 1812. Today on the barrier beach where the inlet was is the shore resort town of Ortley Beach.

[13]Edwin Salter and George C. Beekman,Times in Old Monmouth Historical Reminiscences of Old Monmouth County, New Jersey(Freehold, NJ: The Monmouth Democrat, 1887), 43-45. The three men in the boat with Bacon, after the killing of Studson, fled to New York to escape the wrath of Patriots in the Toms River area; they were forced into British service and eventually deserted, taking Washington’s offer of amnesty for British deserters. Edwin Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 203-204.

[14]Salter and Beckman, Old Times, 45. Bacon’s “gang” numbers most likely included casual followers who joined a specific action; the “core” members are believed to have numbered around nine or ten.

[15]Fowler, Egregious Villains, 252.

[16]Alfred M. Heston, South Jersey, a History, 1664-1924, vol. 1 (New York: Lewis Historical Pub. Co., 1924), 239.

[17]Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 208-209.

[18]Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, Genealogical Record Section, 64.

[19]A nighttime attack was not new to New Jersey – in 1778 there were three night attacks that the Patriots referred as “Massacres”: Hancock House (March – Salem County), Col. Baylor or Tappan (September – Bergen County) and Pulaski’s Legion (October – Burlington County).

[20]“Revolutionary War Sites in Long Beach Island,” www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/long_beach_island_nj_revolutionary_war_sites.htm. There were some errors in the report: the correct spelling of the ship is Alligator; the captain’s name was Steelman not Stillman as seen in the article. The dates given are a little confusing: “yesterday” would have been October 29 – the prize ran aground on the 25th – so it must be referring to the return of the Virginia–the British privateer ship.

[21]Ibid. The Royal Gazette mentions that the ship ran aground on the 25th (Friday) but wasn’t salvaged and attacked until 27th (Sunday). Most histories report the salvaging operation began on the 25th and the attack occurred that night or the early morning of the 26th. Hyson tea is a green tea from China that was highly prized by the British during the eighteenth century.

[22]The area where the “Massacre” took place today is located in the Barnegat Light State Park. Unlike the Sandy Hook Lighthouse built in 1764, the Barnegat Lighthouse (Old Barney) wasn’t built until 1859, it was designed by the then Lt. George Meade of the Army Corps of Engineers; Meade later went on to command the Union Army at Gettysburg.

[23]For further information on Captain Steelman see “American War of Independence at Sea,” Long Beach Island Massacre, www.awiatsea.com/incidents/1782-10-25%20The%20Long%20Beach%20Island%20Massacre.html.

[24]For the role that William Wilson played as an “informer” for John Bacon see:Salter and Beekman, Old Times, 46.

[25]While there are a number of accounts of the “massacre,” as with most stories about the Pine Robbers there is little in the way of official documentation of the massacre. Most of the histories, aside from the Royal Gazette, relied on oral traditions. Interestingly it was not reported in any of the Whig newspapers. Finally, I could not find any mention of what happened to the cargo.

[26]The infantry contingent was led by Capt. Edward Thomas of the Mansfield Township Militia (Burlington County).

[27]Today it is located in Barnegat Township, Ocean County. The Tavern has been restored and in December it is the scene of an annual re-enactment of the skirmish.

[28]New Jersey Gazette, January 8, 1783. For an account of the skirmish from the Loyalist point of view, see New York Gazette and Mercury, January 13, 1783, royalprovincial.com/history/battles/cedarcreek1.shtml.

[29]For a detailed discussion on the role of non-gang members who, nevertheless helped Bacon in his activities see Fowler, Egregious Villains, 268-272.

[30]George F. Fort, MD, “An account of the capture and death of the refugee John Bacon,” Proceeding of the New Jersey Historical Society, vol. I, 1845-1846 (Newark, NJ: Daily Advertiser, 1847), 151-154. George F. Fort was governor of New Jersey (Dem) 1851-1854.

[31]Bacon’s grave is in Arneytown Cemetery, also known as Province Line Road Cemetery, located next to the Brig. Gen. William C. Doyle Veterans Memorial Cemetery. www.findagrave.com/memorial/221197745/john-bacon.

[32]Fowler,Egregious Villains, 276-277. Bacon’s family had originally been Quakers.

[33]Votes and Proceedings of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey, at a Session Begun at Trenton on the 22nd Day of October, 1782, and continued by Adjournments (Trenton: Printed by Isaac Collins, 1783), 126. On page 132 is the approval of the Resolution (June 10, 1783). Cornet John Brown was an officer in the party led by Capt. Stewart.

One thought on “Captain John Bacon: The Last of the Jersey Pine Robbers”

25 October Barnegat Shoals, Long Beach, New Jersey.

Royal Gazette Saturday, November 2, 1782:

The cutter from Ostend, bound to St. Thomas’s, mentioned in our last, ran a-ground on Barnegat Shoals the 25th ultimo. The galley Allegator, Captain Stillman, from Cape May, with 25 men, plundered her on Sunday last of a quantity of Hyson tea, and other valuable articles; but was attacked the same night by Captain John Bacon, and nine men, in a small boat called the Hero’s Revenge, who killed Stillman, wounded the first Lieutenant, and all the privates (four only excepted) were either killed or wounded; the latter were sent to a Doctor, with a flag of truce, by the captors, and the galley was brought in here on Wednesday last.”

Popular history represents this was a massacre by Bacon yet However Private John D. Dennis saw Captain John Scull wounded and Lieutenant Steelman killed. In his affidavit John tells of most of the guards and himself getting clear and running for what he believed to be nine miles in the surf before coming in land. This became known as the Massacre at Long Beach.

Despite it being called a massacre..only two persons are known to be killed and 1 wounded!

Lt Andrew Steelman Andrew Steelman (abt.1750-1782) | WikiTree FREE Family Tree

Reuben Soper Ancestors and Descendants of Reuben Soper-[4099]