On the morning of Saturday, July 14, 1804 the funeral cortège for Alexander Hamilton proceeded northward to Trinity Church where the former Revolutionary War officer and treasury secretary would be interred. Fittingly there was a substantial turnout; in addition to family, friends and the curious public were members of the Society of the Cincinnati, the Chamber of Commerce, and numerous other business and fraternal organizations. Present in the procession too were representatives of the New York Tammany Society. Tammany’s participation in Hamilton’s funeral was likely surprising to many procession watchers given the Society’s well-known anti-Federalist leanings. The man who had fatally wounded the former treasury secretary on the dueling ground—sitting vice president of the United States Aaron Burr—was a major supporter of Tammany and a recipient of its largesse. Indeed, two of the individuals in the entourage that escorted Burr to Weehawken were Tammany men and a third, John Swartwout, waited for Burr at the vice president’s Richmond Hill estate in Manhattan immediately afterward.[1]

men to his duel with Hamilton. (New York Public Library)

The Society’s early years are more nuanced than just its backing of the Democratic-Republicans and Tammany’s presence should not be as shocking as it might seem. Though twenty-first century observers usually associate Tammany with the Gilded Age excesses of William Magear “Boss” Tweed and his cronies, the organization by Tweed’s time was already nearly a century old and had a long track record. Tammany predated the founding of the republic and lasted into the space age, disbanding only in the late 1960s. It was powerful enough in the 1910s to force Franklin Delano Roosevelt to capitulate following an Albany power struggle that the rising New York State assemblyman lost to Tammany’s more seasoned politicos. By the 1920s the pragmatic Roosevelt had made his peace with the organization and as governor occasionally showed up at Tammany’s Fourth of July events, even dedicating its new wigwam on East 17th Street across the street from Union Square on Independence Day 1929. Tammany made and broke the political careers of scores of men and held on to power for nearly two centuries through its leaders’ability to adapt, be different things to different people, and provide the economic, social, and cultural benefits its members and constituents needed to survive.

New York’s Tammany Society was incorporated in May 1789 less than two weeks after George Washington’s inaugural swearing-in at Federal Hall on Wall Street. Its origins date back further. European-Americans’ recognition of Saint Tammany’s Day, as it was eventually called, was a syncretic phenomenon combing elements of Native-American material culture, nomenclature, and rituals with traditional European holidays such as the medieval festival of May Day and annual tributes to such figures as Saints George, Patrick, Andrew, David, and others. Tamina—also spelled Taminend, Tamanend or in other ways until eventually becoming standardized to the more anglicized Tammany—was a Native-American leader reputed to have assisted William Penn in the seventeenth century during the founding of the Pennsylvania Colony. Colonists in Maryland and Pennsylvania recognized and even participated in the annual Native-American tributes to Tamina by at least the mid-eighteenth century. European-American recognition of the famed chieftain reached a new phase on May 1, 1772 when Philadelphians met in the home of one James Byrn and created the Sons of King Tammany Society.[2] Eventually the “King” honorific was replaced with “Saint,” a change which seemingly became permanent in Philadelphia and later elsewhere. In the ensuing years communities in Virginia, New Jersey, Georgia, and other colonies began creating similar societies. New Yorkers did so in 1786.

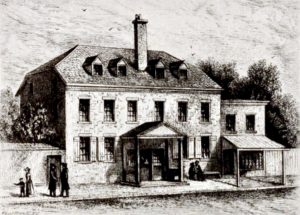

Fraternal organizations were hardly new in New York and a number of others were formed in these same years including St. George’s Society of New York (1770), the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York (1782), the Society of the Cincinnati (1783), and the General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen of the City of New York (1785). The founder of the Tammany movement in New York was William Mooney, an Irish-American active in the Sons of Liberty and later a veteran of the Revolutionary War. An upholster by trade and thus part of New York City’s vibrant tradesmen class, Mooney envisioned a social organization more inclusive than the officers-only Society of the Cincinnati. Membership in the Cincinnati did not preclude one’s potential affiliation within Tammany and there were men who participated in both. The city in 1786 was getting back onto its feet after a difficult decade that included the great fire of 1776 and seven-year British occupation. In January 1785 the Congress of the Confederation moved from Trenton, New Jersey, to New York City Hall, where it would remain through the remainder of the Confederation Period, the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, and subsequent PierreL’Enfant-conversion of City Hall into Federal Hall. There, Washington was sworn in and the First Federal Congress would meet for its first two sessions from March 1789 to August 1790. New York’s Tammany Society was thus well-placed to witness and participate in events.

The documentation of the organization’s activities from 1786 to early 1789 is thin but evidence exists showing conclusively that members met at least semi-regularly. A turning point in the group’s evolution was the drafting of the Tammany constitution and by-laws in May 1789. Mooney and his associates made the decision of switching the Tammany observation from the traditional May 1 of the Julian calendar to the May 12 of the Gregorian. Henceforth May 12 would remain the organization’s anniversary. The group would have a new name as well: The Society of St. Tammany or Columbian Order. Though still largely a social organization Tammany took on a number of semi-official state duties, including welcoming and hosting a delegation of Creek Indians from Georgia led by their mixed-race leader Alexander McGillivray. On July 21, 1790 Mooney and other Tammany members dressed themselves in ersatz Native American clothing and met McGillivray and his men at their ship. From Murray’s Wharf at the bottom of Wall Street the nearly three dozen Creeks with their Tammany honor guard walked the short way to Federal Hall where they met various Cabinet members and legislators. The guests were in New York for several weeks and Tammany fêted the Creeks on August 2, 1790 while the Native Americans negotiated with the Washington Administration on delicate matters regarding land rights and other issues.[3] After much negotiation President Washington and McGillivray signed the Treaty of New York on August 7, 1790.

William Mooney was the New York Society of St. Tammany’s first Grand Sachem, as the group’s leader was called. The second was physician and Columbia College professor William Pitt Smith, who took over in 1790. Another important early leader, though never Grand Sachem, was John Pintard, who before coming to New York had played a part in the founding of New Jersey’s Tammany organization. Throughout his long life this merchant and insurance man played a role in the founding of numerous cultural institutions. Forward-thinking men understood that if the United States were to flourish it must retain its history and memory. There were few real museums in the colonies and the first one, in Charleston, dated only to 1773. Portraitist Charles Wilson Peale created his own museum, situated in his Philadelphia home, in the 1780s. Pintard envisioned a historical and archaeological museum for New York City and his plan gestated in the same period of the Creeks’ visit. Pintard and others pitched the idea that summer and soon broadsides began appearing in local newspapers explaining the museum’s mission and purpose and soliciting materials relating to all aspects of American history, the arts, and natural sciences.

Pintard and museum director Gardiner Baker received a modest space in what was again City Hall after the federal government’s relocation to Philadelphia. When the American Museum opened its doors on May 21, 1791 the public saw that Pintard and Baker had succeeded well given the modest space and limited resources. Items on display included Native-American earthenware, jewelry, weapons, and even literature and hieroglyphics.[4] Pintard, though, dreamed not merely of collecting artifacts and artworks, but creating them. On August 24, 1790 when Manhattan was still the capital Pintard had written to President Washington asking the chief executive to sit for a portrait that presumably was to be hung in Tammany’s American Museum. A Washington aide wrote with polite regrets that the president did not have the time; and besides, the assistant added, like people in New York, every August seemingly in perpetuity, Washington was hoping to get out of town.[5]

In 1794 the American Museum moved to the nearby Exchange Building and Baker took over full ownership on June 25, 1795. He continued building the museum’s collection and even succeeded in acquiring a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington. He took this full-length rendering for display in Boston in 1798 and died in the yellow fever epidemic then afflicting that city.[6] After numerous takeovers in the ensuing years Tammany’s American Museum ended up as part of the holdings of Phineas T. Barnum. Despite devastating financial setbacks in the early years, Pintard himself continued on. In 1804 he helped found the New-York Historical Society. Many years later in a letter to his daughter Pintard explained what he, Gardiner, and their Tammany colleagues had aspired to accomplish with the museum in those early years of the Republic. He wrote to his beloved Eliza on August 13, 1816 that “Mankind cannot always be praying, nor working. Gross dissipation allways prevails where refinement is not cultivated. . . . Theatres, Operas, Academies of Arts, Museums, &c. are to be classed as the means to attract & prevent the growth of vice & immorality.”[7]

The federal government’s permanent departure from Manhattan in 1790 was a hidden blessing that altered New York City’s mission and purpose; New Yorkers thereafter were no longer burdened with the responsibilities that came with hosting the three federal branches of government and all that entailed. In the coming decades and even centuries New Yorkers could focus on what they did best: finance, trade, and culture. New York’s Tammany Society may have become farther removed from the levers of federal power, but it would remain active in political affairs at every level. Throughout the 1790s it was also instrumental in the codification of American civic religion. Tammany celebrated some holidays that most of today’s public scarcely remembers. This is especially true of Evacuation Day, the once widely observed celebration of the November 25, 1783 British packing up and sailing off in return to England. Other holidays continue in the twenty-first century but no longer resonate quite the way they once did. George Washington’s Birthday, observed in most states today as part of Presidents’ Day, was an integral part of American civic culture well into the twentieth century with speeches, parades, and other expressions of veneration. To a disparate people with myriad interests spread across thirteen states, commemorating the birth of the father of their country seemed a good way to bind their fragile young nation together. In some locales people were already pausing each February in their own small manner to note Washington’s birth. Now it was being codified. The New-York Journal, and Weekly Register noted in its February 18, 1790 edition that Philadelphians had celebrated Washington’s Birthday on February 11, the date corresponding to the Julian calendar under which the first president was born. Seven days later the same newspaper informed its readers that the New York Society of St. Tammany had celebrated on the Gregorian date and “Resolved, unanimously, That the 22d day of February (corresponding with the 11th Feb. old stile) be this day, and ever hereafter, commemorated by this Society as the birth dayof the Illustrious George washington.”[8]

Columbian Order for the 1792 tercentenary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage.

Other once-widely celebrated holidays seem to be going away in the twenty-first century, or are being recognized and commemorated in different ways. For none is this truer than Columbus Day. Recognition of Christopher Columbus was something fairly new in early America. Columbus after all was an Genoese Catholic representing the Spanish Crown, which historically had held vast holdings in North America and had frequently been in dispute with the largely Protestant Americans over land boundaries and access to routes of navigation. One of the earliest tributes to the explorer occurred during the July 23, 1788 Federal Procession that took place concurrently with New York State’s ratification convention of the U.S. Constitution. Leading that procession, as described by the New York Daily Advertiser that August 2, was a reenactor named Captain Moore dressed as the Genoese mariner and mounted on horseback.[9] Moore was one of hundreds of people in the procession. In 1792 members of the Columbian Order were eager to commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage. This they did in grand style that October 12. The Columbian Order’s tercentenary commemoration more expressly celebrated Columbus and his opening of the New World to European settlement than the Federal Procession had done. Scores turned out to eat and drink in Lower Manhattan, gathering in remembrance around a fourteen-foot wooden obelisk painted to resemble stone.[10] (Unfortunately, this edifice is apparently no longer extant; 0thers from the same period, amazingly enough, do exist still today.) Though Tammany is often credited with hosting the first Columbus Day that is inaccurate. Baltimoreans for instance also recognized Columbus in 1792 and even did so with an obelisk of their own. Made of more permanent materials than the one built in New York, it was rediscovered in the early 1990s after going lost and found numerous times over the centuries.[11]

The annual event most associated with the New York Tammany Society, for good reason, was Independence Day. Less than half a decade after the Society’s founding, its Fourth of July events and speeches were already a cultural staple. This would remain true moving forward for nearly two centuries until the group’s dissolution at the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. Recognition of Tammany’s Independence Day tradition is why Governor Roosevelt found himself across from Union Square dedicating Tammany’s new wigwam in 1929. Americans recognized the signing of the Declaration of Independence from the first anniversary in 1777. On July 4, 1793 Presbyterian minister Samuel Miller spoke at an especially memorable early Tammany Fourth of July celebration. In that sermon Miller broached a topic that was already causing divisiveness in the Tammany ranks, asking rhetorically about the ongoing French Revolution,

Can we turn our eyes to the European states and kingdoms—can we behold their convulsive struggles, without considering them as all tending to hasten this heavenly aera? Especially, can we view the interesting situation of our affectionate allies, without indulging the delightful hope, that the sparks, which are there seen rising toward heaven, though in tumultuous confusion, shall soon be the means of kindling a general flame, which shall illuminate the darkest and remotest corners of the earth, and pour upon them the effulgence of tenfold glory?[12]

Two months later on September 3 Thomas Jefferson wrote Miller a brief letter thanking the reverend for the copy of the sermon he had sent and concluding that it was “a theme worthy of its occasion.”[13]

Miller’s address in praise of the French Revolution came at an especially stressful time: just three months previously on April 8, French emissary Edmond-Charles Genêt had arrived in Charleston and begun visiting different American cities ingratiating himself with Democratic-Republicans. Genêt’s goal was to generate support for France’s revolutionary cause and gain allies for the rising French tensions with the crown rulers of Europe. Americans were watching Genêt’s movements closely, and to show where he stood, President Washington issued a Neutrality Proclamation on April 22. The unrest in France was a major cause of membership turmoil within New York’s Tammany Society as lines were being drawn between the Federalists who stood against the unfolding French Revolution and the anti-Federalists who across the United States were now organizing themselves into so-called Democratic Societies in favor. Men like Miller and Jefferson believed the events in France, even with the increasing blood being spilled, represented the flowering of Republicanism worldwide. Others, like Edmund Burke and Alexander Hamilton, disagreed.

Acolytes met Genêt with great fanfare throughout his tour. On August 7, 1793 his entourage arrived at Powles Hook Ferry in New Jersey and crossed the North River into Manhattan. There he was met by supporters accessorized in red, white, and blue cockades and other tri-colored expressions of allegiance. The French flag was hung from the Tontine Coffee Shop in the Exchange Building.[14] Liberty caps, an ancient symbol of freedom and now a signal of fidelity to the French revolutionary cause, were proliferating as menswear on the streets. The red Phrygian chapeau would become a Tammany symbol throughout the organization’s long existence. Secretary of State Jefferson had been in regular correspondence with Genêt and now Federalists like Chief Justice John Jay and Senator Rufus King served as Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s eyes and ears on the New York scene. They watched disapprovingly as Democratic-Republicans within both Tammany and the General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen hosted and paid tribute to Citizen Genêt. Though Genêt was eventually recalled and his outreach and attempts to draw the United States into European affairs ultimately came to naught, they exposed numerous fault lines in American politics. These political fissures were stressful within the Tammany membership but not yet enough to bring it to the breaking point.

Tammany may have begun as a non-partisan fraternal organization but friction in its membership was inevitable given the realities of the time. New York’s own Democratic Society was founded in February 1794. Americans were creating these societies in response to the French Revolution, the Washington Administration’s unpopular tax on distilled spirits, and John Jay’s intense, ongoing negotiations with Britain over unresolved issues related to the recent war. Farmers in Western Pennsylvania and surrounding states were threatening insurrection over the excise whiskey tax, and in summer 1794 Washington called out more than 10,000 armed servicemen to quell the unrest. Militarily the Whiskey Rebellion was anti-climactic and little blood was drawn. Politically it drew deeper lines between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. A frustrated President Washington felt he knew where to lay the blame for rising tensions within the nation still just half a decade old, fairly or not, complaining in his November 19, 1794 Message to Congress that, “The arts of delusion were no longer confined to the efforts of designing individuals. The very forbearance to press prosecutions was misinterpreted into a fear of urging the execution of the laws, and associations of men began to denounce threats against the officers employed. From a belief that by a more formal concert their operation might be defeated, certain self-created societies assumed the tone of condemnation.”[15]

Tension only increased the following year in 1795 when details became public of Jay’s concessions to the British. Chief Justice Jay had finalized the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America” in London on November 19, 1794, the same day as Washington’s Sixth Message to Congress in which the president alluded to the Democratic Societies. It took time for news to cross the Atlantic but when it did public condemnation was intense. Despite the ensuing unrest the agreement was eventually ratified by the Senate and signed by President Washington. Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick explain the ramifications in their seminal history The Age of Federalism, averring that “The outpouring of popular feeling over the Jay Treaty, as has long been understood, was more directly responsible than anything else for the full emergence of political parties in America, and of clearly recognized Federalist and Republican points of view on all political questions.”[16] Naturally these tensions spilled over into the New York Tammany Society. Federalists had increasingly been leaving the organization in this period, essentially placing the organization in the hands of the supporters of the Democratic-Republicans in the lead-up to the 1796 election and beyond. Tammany’s political sensibility would remain broadly the same for the next century and a half even as the issues New Yorkers and Americans faced evolved, political parties dissolved and realigned themselves under different names and guises, and men came and left the scene.

Tammany was well-positioned to play a role in American affairs given its institutional memory and the significant role it had already played in establishing important aspects of American culture and iconography that remain with us today. In these early years Aaron Burr in particular ingratiated himself within the Tammany support structure in hopes of catapulting himself into the Executive Mansion. The ignominy of the duel brought those aspirations to an end. The New York Tammany Society gained further imprimatur the following year when on April 8, 1805 New York State granted it a charter as a charitable organization. This designation is somewhat curious given Tammany’s increasingly overt political endeavors over the past decade. Its name too received a subtle tweak and became The Society of Tammany or Columbian Order in the City of New York.[17]As the nineteenth century progressed what widely came to be called Tammany Hall, nominally distinct from the Tammany Society but essentially one and the same, became synonymous with the New York County Democratic Committee. Tammany only grew and was strong enough to survive the squalor and excesses of men like Boss Tweed, whose greed and profligacy had led to understandable public outrage and recrimination in the late nineteenth century. The final Grand Sachem, Harlem powerbroker J. Raymond Jones, stepped down on March 10, 1967.[18]

[1]Peter L. Bernstein, Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 245.

[2]Francis Von A.Cabeen,“The Society of the Sons of Saint Tammany of Philadelphia,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 25, no. 4 (1901): 442.

[3]St. Tammany’s Society, “To George Washington from the St. Tammany’s Society, 24 August 1790 [Letter Not Found],” Founders Online, National Archives, August 24, 1790. founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0150.

[4]John W. Francis, Old New York; or, Reminiscences of the Past Sixty Years (NewYork,Charles Roe, 1858), 124.

[5]St. Tammany’s Society, “To George Washington from the St. Tammany’s Society, 24 August 1790 [Letter Not Found].”

[6]Winifred E. Howe, A History of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with a Chapter on the Early Institutions of Art in New York (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1913), 5-6.

[7]JohnPintard, Letters from John Pintard to His Daughter, Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson, 1816-1833,ed. Dorothy C. Barck and Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson, Vol. I (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1940), 25-26.

[8]George Washington, diary entry, February 11, 1790, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0001-0002-0011.

[9]John P.Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, Richard Leffler, Charles H. Schoenleber, and Margaret A. Hogan, eds., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/description_of_the_new_york.pdf.

[10]Timothy Winkle,“The Monument That Created Columbus,” National Museum of American History Behring Center, October 12, 2020, americanhistory.si.edu/blog/created-columbus.

[11]“Columbus Obelisk Discovered Again,” Baltimore Sun, May 22, 1992, www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1992-05-22-1992143054-story.html.

[12]Samuel A. Miller, Sermon, Preached in New-York, July 4th, 1793 (New York: Thomas Greenleaf, 1793), 30.

[13]Thomas Jefferson,“From Thomas Jefferson to Samuel Miller, 3 September 1793.” Founders Online, National Archives, September 3, 1793. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-27-02-0025.

[15]George Washington, “Washington’s Sixth Annual Message to Congress,” The Papers of George Washington Project at the University of Virginia, November 19, 1794, washingtonpapers.org/documents/washingtons-sixth-annual-message-to-congress/.

[16]Stanley Elkinsand Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism – The Early American Republic, 1788 – 1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 415.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...